by Susan Flantzer

- Brabourne Family Connections

- Timeline: March 1, 1915 – March 31, 1915

- A Note about German Titles

- Royals/Nobles/Peers Who Died in Action

Wyndham Knatchbull-Hugessen, 3rd Baron Brabourne; Photo Credit – www.illustratedfirstworldwar.com

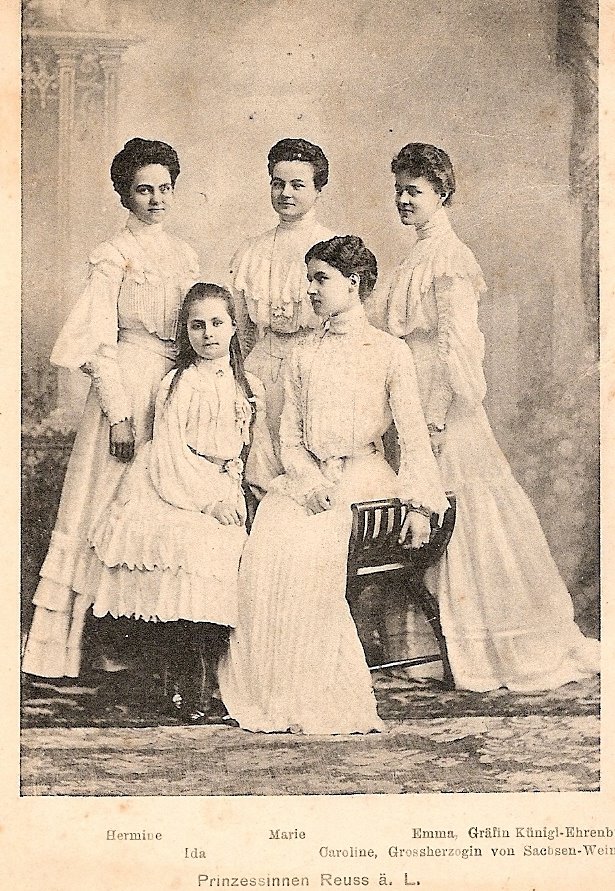

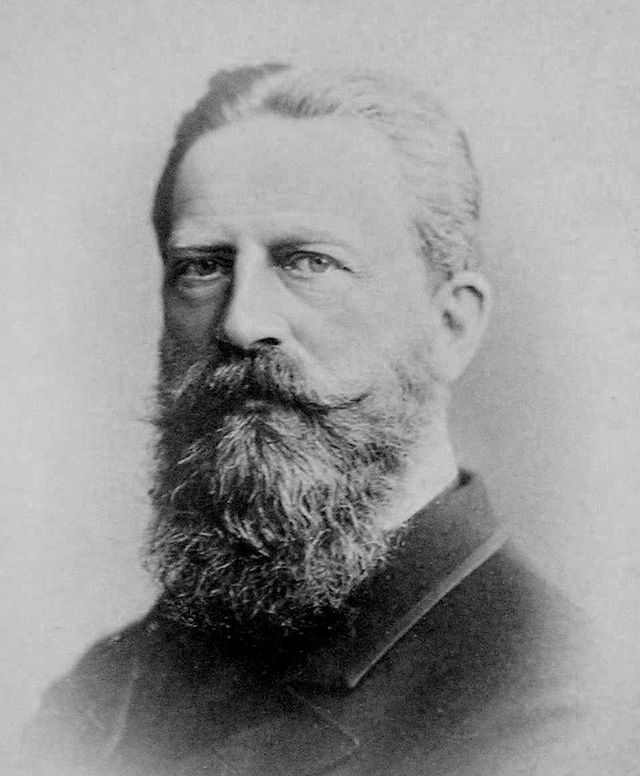

On March 11, 1915, 29-year-old Wyndham Knatchbull-Hugessen, 3rd Baron Brabourne was killed in action in World War I. On March 10, 1915, during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards took up reserve positions near Neuve Chapelle, France. On March 11, 1915, the battalion sustained heavy casualties while crossing the Rue Tilleloy. The battalion’s war diary recorded the death of Lord Brabourne together with 15 other officers and 325 other soldiers. Lord Barbourne has no known grave, but his name appears on the La Touret Memorial in Bethune, France. His family erected a memorial for him in the parish church in Smeeth, England.

As the 3rd Baron Brabourne was unmarried and had no heir, his first cousin Cecil Knatchbull-Hugessen succeeded him as the 4th Baron Brabourne. The peerage continued to be inherited from father to son until Norton Knatchbull, 6th Baron Brabourne, who was captured and executed by the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) during World War II. The 6th Baron Brabourne’s brother John then became the 7th Baron Brabourne as his brother had died unmarried.

Wikipedia: Baron Brabourne

The names Brabourne and Knatchbull may sound familiar to many British royal family enthusiasts. The current Baron Brabourne, Norton Knatchbull, 8th Baron Brabourne, is the son of John Knatchbull, 7th Baron Brabourne and Patricia Mountbatten, 2nd Countess Mountbatten of Burma. His mother Patricia is the elder daughter of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma who was a great grandson of Queen Victoria. Patricia is also a first cousin of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. The family’s descent from Queen Victoria comes from her third child Princess Alice who married Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine.

Queen Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha → Princess Alice married Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine → Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine married Prince Louis of Battenberg (later Louis Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven) → Prince Louis of Battenberg (later of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma) married Edwina Ashley → Patricia Mountbatten, 2nd Countess Mountbatten of Burma married John Knatchbull, 7th Baron Brabourne → Norton Knatchbull, 8th Baron Brabourne

Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma was killed in 1979 by a Provisional Irish Republican Army bomb placed in his fishing boat. Also killed was Nicholas Knatchbull, a son of Lord Mountbatten’s elder daughter Patricia, Patricia’s mother-in-law the Dowager Lady Brabourne, and Paul Maxwell, a 15-year-old crew member.

Unofficial Royalty: Tragedy in the British Royal Family at the End of August (scroll down to Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma)

Upon his father’s death in 2005, Norton Knatchbull became the 8th Baron Brabourne. He will become 3rd Earl Mountbatten of Burma upon the death of his mother Patricia, 2nd Countess Mountbatten of Burma. Patricia was able to succeed to her father’s title because the peerage had been created with special remainder to the 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma’s daughters and their heirs male.

Wikipedia Earl Mountbatten of Burma

*********************************************************

Timeline: March 1, 1915 – March 31, 1915

- March 10 – March 13 – Battle of Neuve Chapelle in the Artois region of France

- March 22 – The Siege of Przemyśl ends, Russians capture the fortress

*********************************************************

Most of the royals who died in action during World War I were German. The German Empire consisted of 27 constituent states, most of them ruled by royal families. Scroll down to German Empire here to see what constituent states made up the German Empire. The constituent states retained their own governments, but had limited sovereignty. Some had their own armies, but the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. In wartime, armies of all the constituent states would be controlled by the Prussian Army and the combined forces were known as the Imperial German Army. German titles may be used in Royals Who Died In Action below. Refer to Unofficial Royalty: Glossary of German Noble and Royal Titles.

24 British peers were also killed in World War I and they will be included in the list of those who died in action. In addition, more than 100 sons of peers also lost their lives, and those that can be verified will also be included.

*********************************************************

March 1915 – Royals/Nobles/Peers Who Died In Action

The list is in chronological order and does contain some who would be considered noble instead of royal. The links in the last bullet for each person is that person’s genealogical information from Leo’s Genealogics Website or to The Peerage website. If a person has a Wikipedia page, their name will be linked to that page.

The Honorable William Eden

- son of William Morton Eden, 5th Baron Auckland and Sybil Hutton

- born June 15, 1892

- unmarried

- killed in action March 2, 1915, age 22

- http://www.genealogics.org/getperson.php?personID=I00247020&tree=LEO

Prince Alexander of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, Prince of Ratibor-Corvey

- son of Prince Egon of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, Prince of Ratibor-Corvey and Princess Leopoldine of Lobkowicz

- born October 16, 1894 in Coburg, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha

- unmarried

- killed in action at Zywasow, Galicia, Poland on March 7, 1915, age 20

- http://www.ourfamilyhistories.org/getperson.php?personID=I112141&tree=00

Howard Stonor

- son of Francis Stonor, 4th Baron Camoys and Jessica Carew

- born April 2, 1893

- unmarried

- killed in action March 10, 1915, age 21

- http://thepeerage.com/p20018.htm#i200176

Wyndham Knatchbull-Hugessen, 3rd Baron Brabourne

- son of Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen, 2nd Baron Brabourne and The Honorable Amy Beaumont

- born September 21, 1885

- unmarried

- killed in action at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in France March 11, 1915, age 29

George Douglas-Pennant

- son of George Douglas-Pennant, 2nd Baron Penrhyn and Gertrude Glynneborn August 26, 1876 in Torquay, Devon, England

- unmarried

- killed in action at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in France on March 11, 1915, age 38

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p5281.htm#i52802