by Susan Flantzer

- November 18, 1916: End of the Battle of the Somme

- November 21, 1916: Death of Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary

- Timeline: November 1, 1916 – November 30, 1916

- A Note About German Titles

- November 1916 – Royals/Nobles/Peers/Sons of Peers Who Died In Action

**********************************************************

November 18, 1916: End of the Battle of the Somme

“Somme. The whole history of the world cannot contain a more ghastly word.” These were the words of Friedrich Steinbrecher, a 24-year-old German officer and theology student who fought in the Battle of the Somme and survived, but was killed in action in 1917 in Champagne, France.

The Battle of the Somme was a 141-day battle, more accurately called the Somme Offensive, that lasted from July 1, 1916 until November 18, 1916. Fought in northern France near the Somme River, the battle pitted the British and French forces against the German forces. By November 18, 1916, when the battle ended, British and French forces had penetrated only 6 miles (9.7 km) into German-occupied territory and more than 1,300,000 soldiers from all countries involved were dead or wounded, making the Battle of the Somme one of the bloodiest battles in history. The British and the French won a Pyrrhic victory, a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is equivalent to a defeat. The phrase Pyrrhic victory is named after King Pyrrhus of Epirus, whose army suffered irreplaceable casualties in defeating the Romans at Heraclea in 280 BC and Asculum in 279 BC during the Pyrrhic War.

To learn more about the Battle of the Somme, see:

*********************************************************

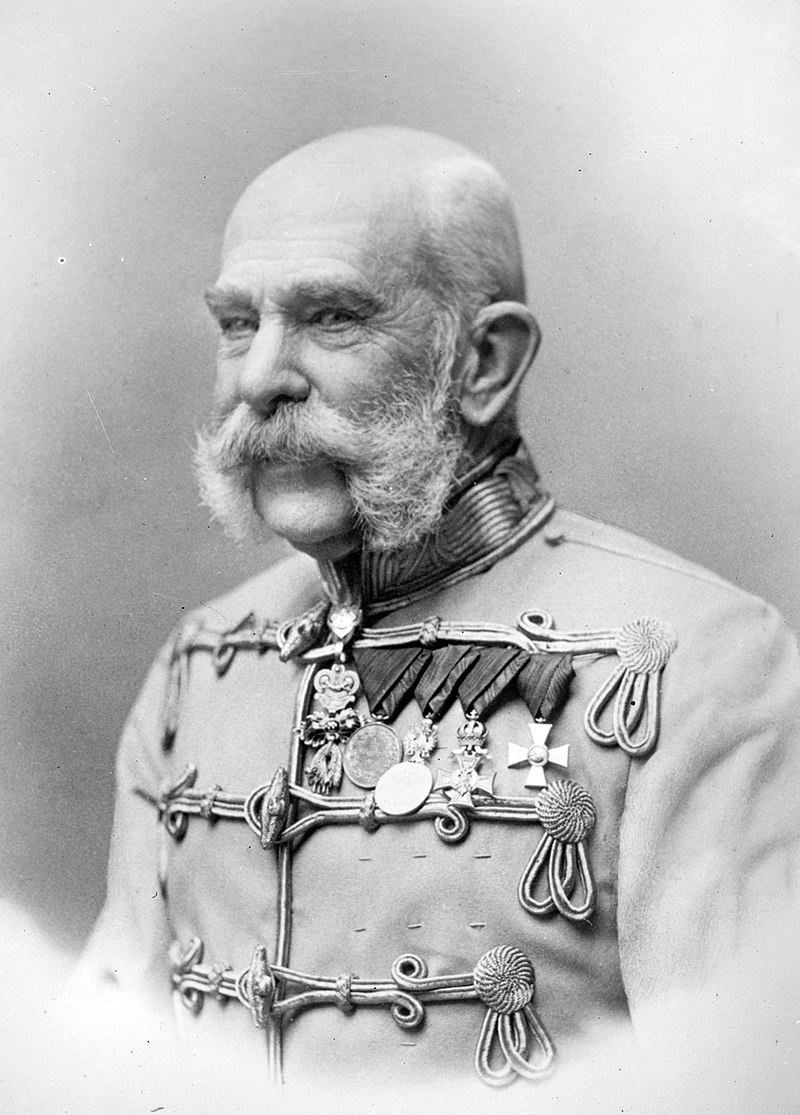

November 21, 1916: Death of Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary

Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary died on November 21, 1916, in the middle of World War I, at the age of 86 at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, Austria. He is the third longest reigning European monarch (nearly 68 years) after King Louis XIV of France (72 years) and Johann II, Prince of Liechtenstein (70 years). During World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was part of the Central Powers or Quadruple Powers along with the German Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria.

Leaders of the Central Powers (left to right): Wilhelm II, German Emperor; Franz Joseph, Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary; Mehmed V, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire; and Ferdinand I, Tsar of Bulgaria; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Born on August 18, 1830 at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, Austria, 18-year-old Franz Joseph succeeded to the throne on December 2, 1848 upon the abdication of his uncle Ferdinand who suffered from epilepsy, hydrocephalus, and neurological problems.

Franz Joseph married Elisabeth of Bavaria (known as Sisi) on April 24, 1854 at the Augustinerkirche, the parish church of the imperial court of the Habsburgs, a short walk from Hofburg Palace in Vienna. The ceremony was conducted by Cardinal Joseph Othmar Rauscher, Archbishop of Vienna with 1,000 guests in attendance including 70 bishops.

Emperor Franz Joseph in 1853; Credit – Wikipedia

Empress Elisabeth in 1855; Credit – Wikipedia

The couple had four children:

-

- Archduchess Sophie (1855 – 1857), died in childhood

- Archduchess Gisela (1856 – 1932), married Prince Leopold of Bavaria, had issue

- Crown Prince Rudolf (1858 – 1889), married Princess Stephanie of Belgium, had issue

- Archduchess Marie Valerie (1868 – 1924), married Archduke Franz Salvator, Prince of Tuscany, had issue

Franz Joseph’s family endured several tragic, violent deaths:

- June 19, 1867: Franz Joseph’s brother, Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico, was executed by a firing squad.

- January 30, 1889: Franz Joseph’s only son and heir to the throne, Crown Prince Rudolf, in an apparent suicide plot, shot his 17-year-old mistress Baroness Mary Vetsera and then shot himself at Mayerling, a hunting lodge in the Vienna Woods.

- September 10, 1898: Franz Joseph’s wife, Empress Elisabeth (Sisi) was stabbed to death by a 25-year-old Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni while walking to the shore of Lake Geneva to catch a steamship.

- June 28, 1914: Franz Joseph’s nephew and heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia, an act which led to the start of World War I.

Unofficial Royalty: June 28, 1914 – Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne

In early November of 1916, Franz Joseph was suffering from a chronic lung inflammation which then developed into pneumonia. Despite a persistent high fever, the 86-year-old emperor continued his daily routine with his immense workload literally until the day he died. In the afternoon of November 21, 1916, Franz Joseph’s condition rapidly deteriorated, but he remained at his desk working until 7 PM when he allowed his valet to help him to bed. Franz Joseph died shortly after 9 PM. His great nephew succeeded him as Emperor Karl I of Austria, but only reigned for two years as the monarchy was abolished at the end of World War I.

Coffin of Franz Joseph lying in state at the Hofburg Palace chapel; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Franz Joseph’s body lay in state for three days at Hofburg Palace. The funeral took place on November 30, 1916. With all the bells of Vienna’s churches ringing and thousands of mourners lining the streets of Vienna, the coffin of the late Emperor was taken from Hofburg Palace to St. Stephen’s Cathedral where a short service was attended by Emperor Karl I, his wife Empress Zita (of Bourbon-Parma) and the heir to the throne four-year-old Crown Prince Otto.

After the service, the Emperor, the Empress, and the Crown Prince were joined by King Ludwig III of Bavaria, King Friedrich August of Saxony, Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria and Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany representing his father Wilhelm II, German Emperor to follow the funeral cortege on foot as the remains of Franz Joseph were transported to the Kaisergruft (Imperial Crypt) in the Capuchin Church, the traditional burial place of the Habsburgs, where Franz Joseph was buried between his wife and his son. Two days later, on the 68th anniversary of Franz Joseph’s accession to the throne, a final requiem mass was celebrated in the Hofburg Palace chapel attended by the Imperial Family and court dignitaries.

Unofficial Royalty: A Visit to the Kaisergruft (Imperial Crypt) in Vienna

You Tube: Funeral Procession of Emperor Franz Joseph

Funeral Procession for Emperor Franz Joseph, in front: Empress Zita and Emperor Karl with their oldest son Crown Prince Otto; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Tomb of Emperor Franz Ferdinand with the tomb of Empress Elisabeth on the left and the tomb of Crown Prince Rudolf on the right; Photo Credit – Susan Flantzer, August 2012

See Unofficial Royalty: Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary for a more complete biography.

*********************************************************

Timeline: November 1, 1916 – November 30, 1916

- July 1 – November 18 – Battle of the Somme in Somme, Picardy, France

- October – November – First Battle of the Crna Bend, near the Crna River in Macedonia and Serbia, a phase of the Monastir Offensive

- October 1 – November 5 – Battle of Le Transloy in Le Transloy, France, last stage of the Battle of the Somme

- October 1 – November 11 – Battle of Ancre Heights in Ancre, France, last stage of the Battle of the Somme

- November 1–4 – Ninth Battle of the Isonzo in the Soča River valley in present-day Slovenia

- November 13–18 – Battle of the Ancre (closing phase of the Battle of the Somme) near the Ancre River in Picardy, France

- November 18 – The Battle of the Somme ends with enormous casualties and an English-French advantage

- November 21 – HMHS Britannic sinks after hitting a German mine

- November 21 – Franz Joseph I, Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, dies and is succeeded by Karl I (see above)

- November 25 – December 3 – Battle of Bucharest, a phase of the conquest of Romania, in Romania, the capital of Romania

- November 28 – Prunaru Charge, a phase of the Battle of Bucharest, Romanian cavalry desperately charge into enemy lines

*********************************************************

A Note About German Titles

Many German royals and nobles died in World War I. The German Empire consisted of 27 constituent states, most of them ruled by royal families. Scroll down to German Empire here to see what constituent states made up the German Empire. The constituent states retained their own governments, but had limited sovereignty. Some had their own armies, but the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. In wartime, armies of all the constituent states would be controlled by the Prussian Army and the combined forces were known as the Imperial German Army. German titles may be used in Royals Who Died In Action below. Refer to Unofficial Royalty: Glossary of German Noble and Royal Titles.

24 British peers were also killed in World War I and they will be included in the list of those who died in action. In addition, more than 100 sons of peers also lost their lives, and those that can be verified will also be included.

*********************************************************

November 1916 – Royals/Nobles/Peers/Sons of Peers Who Died In Action

The list is in chronological order and does contain some who would be considered noble instead of royal. The links in the last bullet for each person is that person’s genealogical information from Leo’s Genealogics Website or to The Peerage website. If a person has a Wikipedia page, their name will be linked to that page.

Captain Auberon Thomas Herbert, 9th Baron Lucas and 5th Baron Dingwall

- son of The Honorable Auberon Herbert, younger son of Henry Herbert, 3rd Earl of Carnarvon and Lady Florence Cowper, daughter of George Cowper, 6th Earl Cowper

- born May 25, 1876

- unmarried

- Captain in the Royal Flying Corps

- wounded by bullets from German fighter aircraft during a flight over Haplincourt, France November 3, 1916, died of his wounds the same day, age 40

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p17051.htm#i170502

- only child of Prince Arnulf of Bavaria, youngest son of Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria, and Princess Therese of Liechtenstein, daughter of Aloys II, Prince of Liechtenstein

- born June 24, 1884 in Munich, Bavaria (Germany)

- unmarried

- Major in the in charge of the 3rd Battalion of the Deutsches Alpenkorps

- killed in action at Monte Sule, Transylvania, Romania on November 8, 1916, age 32

- buried at Theatinerkirche in Munich, Bavaria

Lieutenant Commander The Honorable Philip Sidney Campbell

- 3rd son of Patrick Campbell, 1st Baron Glenavy and Emily MacCullagh

- born February 5, 1893

- unmarried

- Lieutenant Commander in the Drake Battalion, Royal Naval Division

- killed in action at Beaumont-Hamel, France during the Battle of the Somme November 13, 1916, age 23

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p31824.htm#i318236

Lieutenant The Honorable Vere Sidney Tudor Harmsworth

- son of Harold Sidney Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere and Mary Lilian Share

- born September 25, 1895

- unmarried

- Lieutenant in the Hawke Battalion, Royal Naval Division

- elder brother Captain Hon. Harold Alfred Vyvyan St. George Harmsworth also died in World War I (on February 12, 1918)

- killed in action at Beaumont-Hamel, France during the Battle of the Somme November 13, 1916, age 21

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p7351.htm#i73503

Lieutenant The Honorable Frederic Sydney Trench

- eldest son of Frederic Oliver Trench, 3rd Baron Ashtown and Violet Grace Cosby

- born 9 December 9, 1894 at Woodlawn, Kilconnell, County Galway, Ireland

- unmarried

- Lieutenant in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps

- killed in action November 16, 1916

- http://www.thepeerage.com/p3040.htm#i30399

Prince Heinrich XLI Reuss

- son of Prince Heinrich XXIV Reuss of Köstritz and Princess Elisabeth Reuss of Köstritz

- born September 2, 1892 in Ernstbrunn, Austria

- unmarried

- killed in action at Bivolita, Romania November 29, 1916, age 24

- http://thepeerage.com/p11134.htm#i111340