by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2017

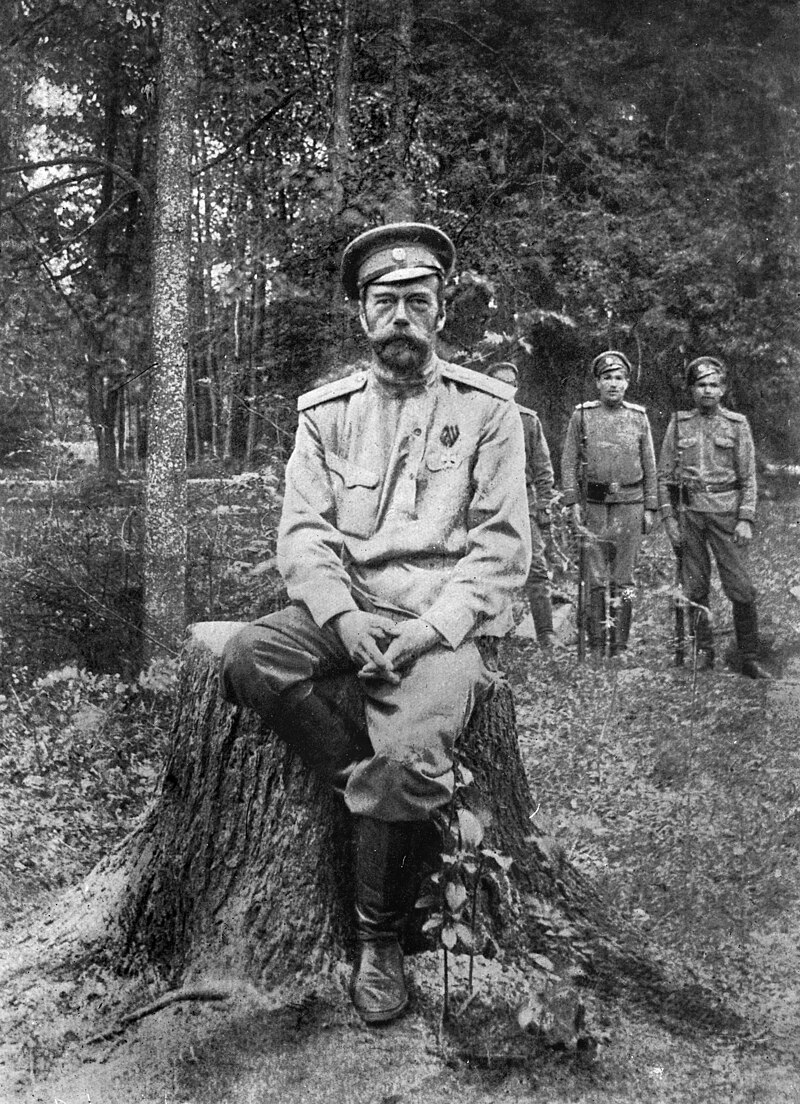

Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, 1912; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia was born on May 18, 1868, the eldest son of Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia and Princess Dagmar of Denmark, known as Maria Feodorovna after her marriage. He became Tsar at the age of 26 upon the death of his father on November 1, 1894. Shortly afterward, on November 26, 1894, Nicholas married Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, the youngest surviving child of Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine and Princess Alice of the United Kingdom and a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. After her marriage, Alix was known as Alexandra Feodorovna.

Nicholas and his wife were related to many other royals. Nicholas was a grandson of King Christian IX of Denmark, the maternal nephew of King Frederik VIII of Denmark, King George I of Greece, and Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom (wife of King Edward VII). Among his first cousins were King George V of the United Kingdom, King Christian X of Denmark, King Haakon VII of Norway and his wife Queen Maud (daughter of King Edward VII), King Constantine I of Greece and Prince Andrew of Greece, the father of Prince Philip, The Duke of Edinburgh.

Alexandra was the granddaughter of Queen Victoria; the niece of King Edward VII of the United Kingdom; Victoria, Princess Royal, German Empress and Queen of Prussia (wife of Friedrich III, German Emperor); Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; and Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Her first cousins included Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Queen Sophie of Greece, King George V of the United Kingdom, Queen Maud of Norway, Queen Marie of Romania, Albert, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, Crown Princess Margaret of Sweden, Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain.

Nicholas and Alexandra had four daughters and one son. Their son, Alexei, the heir to the throne, was a sufferer of the blood-clotting genetic disease hemophilia. Alexandra’s grandmother Queen Victoria was a hemophilia carrier. Queen Victoria’s son Leopold suffered from hemophilia and it is assumed that a spontaneous mutation occurred in Queen Victoria. Alexandra’s brother Friedrich was a hemophilia sufferer who had died at the age of two from a brain hemorrhage after falling out a window, so therefore her mother Alice was a hemophilia carrier.

Russian Imperial Family (between circa 1913 and circa 1914); Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Nicholas mobilized the Russian troops in 1914 which led to Russia’s entrance into World War I on the side of Entente Powers (also known as the Allies of World War I or the Allies). See Unofficial Royalty: World War I: Who Was On What Side? In the midst of World War I, the February Revolution, the first of two revolutions in Russia, took place in 1917. Later in 1917, the October Revolution occurred, paving the way for the establishment of the Soviet Union.

Historian Alexander Rabinowitch in The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd, summarized the reasons for the February Revolution: The February 1917 revolution “… grew out of prewar political and economic instability, technological backwardness, and fundamental social divisions, coupled with gross mismanagement of the war effort, continuing military defeats, domestic economic dislocation, and outrageous scandals surrounding the monarchy.” The revolution was confined to the capital St. Petersburg and its surrounding areas and lasted less than a week. It involved mass demonstrations and armed clashes with police and forces of the Russian army. The immediate result of the revolution was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire.

By March 12, 1917, all the remaining regiments of the Russian Imperial Army had mutinied. A Provisional Government was formed which issued a demand that Nicholas must abdicate. At this time, Nicholas was not in St. Petersburg, but at the Stavka, the headquarters of the Russian Imperial Army in Mogilev (now in Belarus), 500 miles/800km away, living on the Imperial Train. Despite many earlier warnings from many people that he should return to the capital, Nicholas remained at the Stavka.

Finally, when it was too late to take any action, Nicholas decided to return to his family at Tsarskoe Selo, 15 miles/24 km from St. Petersburg, the site of Alexander Palace, the family’s favorite residence. Aboard the train, Nicholas heard the news that the last of the regiments had mutinied and he realized he had no choice but to abdicate. On March 15, 1917, aboard the Imperial Train headed to Tsarskoe Selo, Nicholas signed the abdication manifesto. At first, he decided to abdicate in favor of his son Alexei, but he changed his mind after conferring with doctors who said the hemophiliac Alexei would not survive without his parents, who would surely be exiled. Nicholas then decided to abdicate in favor of his brother Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich. However, Michael declined to accept the throne unless the people were allowed to vote for the continuation of the monarchy or for a republic.

Nicholas issued the following statement:

“In the days of the great struggle against the foreign enemies, who for nearly three years have tried to enslave our fatherland, the Lord God has been pleased to send down on Russia a new heavy trial. Internal popular disturbances threaten to have a disastrous effect on the future conduct of this persistent war. The destiny of Russia, the honor of our heroic army, the welfare of the people and the whole future of our dear fatherland demand that the war should be brought to a victorious conclusion whatever the cost. The cruel enemy is making his last efforts, and already the hour approaches when our glorious army together with our gallant allies will crush him. In these decisive days in the life of Russia, We thought it Our duty of conscience to facilitate for Our people the closest union possible and a consolidation of all national forces for the speedy attainment of victory. In agreement with the Imperial Duma We have thought it well to renounce the Throne of the Russian Empire and to lay down the supreme power. As We do not wish to part from Our beloved son, We transmit the succession to Our brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, and give Him Our blessing to mount the Throne of the Russian Empire. We direct Our brother to conduct the affairs of state in full and inviolable union with the representatives of the people in the legislative bodies on those principles which will be established by them, and on which He will take an inviolable oath. In the name of Our dearly beloved homeland, We call on Our faithful sons of the fatherland to fulfill their sacred duty to the fatherland, to obey the Tsar in the heavy moment of national trials, and to help Him, together with the representatives of the people, to guide the Russian Empire on the road to victory, welfare, and glory. May the Lord God help Russia!”

One of the last photographs taken of Nicholas II, take Tsarskoe Selo after his abdication, Spring 1917; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Nicholas and his family were held under house arrest first at the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo, and later at the Governor’s Mansion in Tobolsk, Siberia between August 1917 – April 1918. In April 1918, they were moved to the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, Siberia. It was here on the morning of July 17, 1918, that the family was brought to a room in the basement and assassinated.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- “February revolution.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Feb. 2017. Web. 11 Feb. 2017.

- Lincoln, Bruce W., and Lincoln. The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY, Unofficialtes: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1983. Print.

- “Nicholas II of Russia.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Feb. 2017. Web. 11 Feb. 2017.

- Perry, John Curtis, and Constantine Pleshakov. The Flight of the Romanovs: A Family Saga. New York, NY, United States: William S. Konecky Associates, 1999. Print.

- Rabinowitch, Alexander. The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2008. Print.

- Scott. “Emperor Nicholas II of Russia.” Russian Royals. Unofficial Royalty, 28 Mar. 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2017.