by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2017

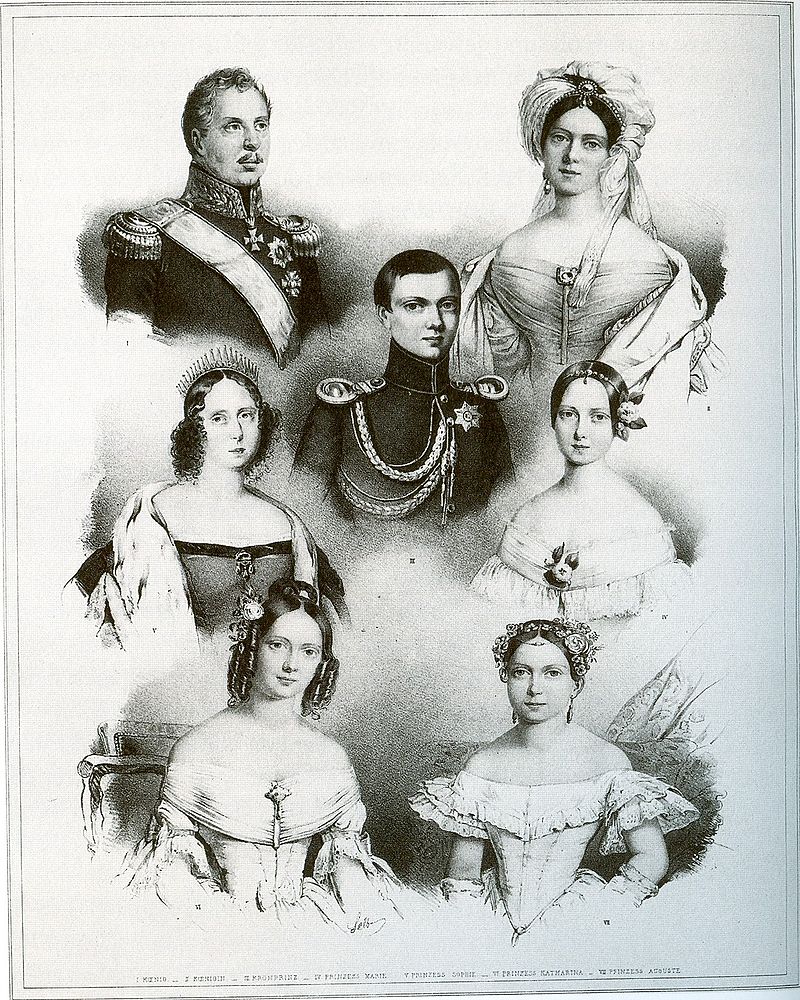

Elizabeth de Burgh, Queen of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

Born in Ireland around 1284, Elizabeth de Burgh was the second wife of Robert I (the Bruce), King of Scots and his only Queen Consort. Robert’s first wife Isabella of Mar died in childbirth before Robert became king. Elizabeth was the third of the ten children of Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster and 3rd Baron of Connaught and his wife Margaret, possibly his cousin Margaret de Burgh or Margaret de Guines.

Elizabeth had nine siblings:

- Aveline de Burgh (born circa 1280), married John de Bermingham, 1st Earl of Louth, had issue

- Eleanor de Burgh (1282 – after August 1324), married Lord Thomas de Multon of Gilsland, had one daughter

- Walter de Burgh (circa 1285 – 1304)

- John de Burgh (c. 1286 – 1313), married Elizabeth de Clare, granddaughter of King Edward I of England, had one son

- Matilda de Burgh (circa 1288 – 1320), married Gilbert de Clare, 8th Earl of Gloucester, 7th Earl of Hertford, 10th Lord of Clare, 5th Lord of Glamorgan, grandson of King Edward I of England, no issue

- Thomas de Burgh (circa 1292 – 1316)

- Catherine de Burgh (circa 1296 – 1331), married Maurice Fitzgerald, 1st Earl of Desmond, had one son

- Edmond de Burgh ( 1298 – 1338), married ?, had issue

- Joan de Burgh (circa 1300 – 1359), married (1) Thomas FitzGerald, 2nd Earl of Kildare, had issue (2) Sir John Darcy, 1st Baron Darcy de Knayth, had issue

Elizabeth’s father Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster and 3rd Baron of Connaught was one of the most powerful Irish nobles of his time. He was the friend and ally of King Edward I of England and ranked first among the Earls of Ireland. He played a leading role among the Anglo-Irish nobility, supporting the expansion of the Norman barons in Ireland at the expense of the ancestral territories of the Irish Gaelic. Despite the marriage of his daughter to Robert the Bruce, that did not stop him from leading his forces from Ireland to support England’s King Edward I in his Scottish campaigns.

Through her father, Elizabeth was the descendant of the Irish Kings of Munster, Kings of Thomond, and also of the famous Brian Boru, High King of Ireland. Her father also had a line of descent from William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, called William the Marshal, the Anglo-Norman soldier and statesman who served five English kings: Henry II, his sons Henry the Young King, Richard I, John, and John’s son Henry III.

Richard’s great-granddaughter Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster married Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence who was the third, but the second surviving son of King Edward III of England and was one of the two people on whom the House of York would base its claim to the English throne during the Wars of the Roses.

de Burgh Arms; Credit – By Sodacan – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27269486

Elizabeth probably met Robert the Bruce, then the Earl of Carrick, at the English court. Today, Earl of Carrick is one of the titles of the eldest living son and heir-apparent of the British sovereign. Along with Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick was one of the traditional titles of the eldest living son and heir-apparent of the throne of Scotland. When King James VI of Scotland also became King James I of England after the death of Queen Elizabeth I, the Scottish titles came along with him.

Elizabeth and Robert married at Writtle, near Chelmsford, Essex, England in 1302 when Elizabeth was about 18 years-old and Robert was about 28 years-old. This was the second marriage for Robert. His first wife Isabella of Mar died soon after giving birth to a daughter named Marjorie Bruce on December 12, 1296. Marjorie married Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland. It was Marjorie’s son who succeeded to the Scots throne as King Robert II, the first monarch of the House of Stewart, after the death of Elizabeth and Robert the Bruce’s childless son King David II.

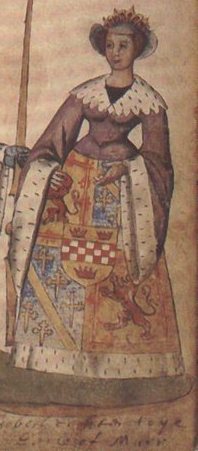

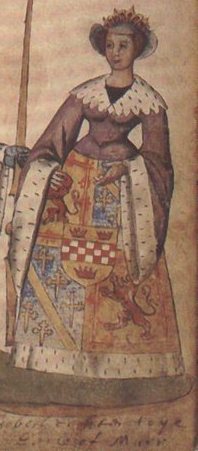

Robert the Bruce and Elizabeth de Burgh from Seton Armorial in the Nation Library of Scotland (MS Acc. 9309); Credit – Wikipedia

In 1302, when Elizabeth married Robert the Bruce, Scotland had been in political turmoil for some time. Alexander III, King of Scots (reigned 1249 – 1286) had only two surviving children, a son Alexander and a daughter Margaret who married King Eric II of Norway. Margaret of Scotland, Queen of Norway died in childbirth in 1283, giving birth to her only child Margaret, Maid of Norway. In 1284, the earls and barons of Scotland recognized Margaret, Maid of Norway as the heir to the throne of her grandfather King Alexander III of Scotland if he died without a male heir. Later that year, Alexander III’s 20-year-old Alexander died. When Alexander III died in 1286, his three-year-old granddaughter was the heir to his throne. The earls, barons, and clerics of Scotland met to select the Guardians of Scotland who would rule the kingdom for the rightful heir. In 1290, while on her way to Scotland, Margaret, Maid of Norway died.

The death of Margaret, Maid of Norway began a two-year interregnum in Scotland caused by the succession crisis. With Margaret’s death, the line of William I (the Lion), King of Scots became extinct and there was no obvious heir by primogeniture. Fifteen candidates presented themselves as candidates for the throne of Scotland. The most prominent were John Balliol, great-grandson of William I’s younger brother David, Earl of Huntingdon, and Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, David of Huntingdon’s grandson and the grandfather of Elizabeth’s husband.

The Scottish lords invited King Edward I of England to arbitrate the claims. Edward I agreed but forced the Scots to swear allegiance to him as their overlord. In 1292, it was decided that John Balliol should become King of Scots. After John Balliol became King, Robert, 5th Lord of Annandale resigned the lordship of Annandale and his claim to the throne to his eldest son Robert de Brus, the father of Elizabeth’s husband. Around the same time, Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale’s wife Marjorie, Countess of Carrick died, and the Earldom of Carrick, which Robert had ruled jure uxoris (by right of his wife), devolved upon their eldest son, also called Robert, Elizabeth’s husband. John Balliol proved weak and incapable, and in 1296 was forced to abdicate by Edward I, who then attempted to annex Scotland into the Kingdom of England. For ten years, there was no monarch of Scotland.

The Scots refused to tolerate English rule and the result was the Wars of Scottish Independence, a series of military campaigns fought between Scotland and England, first led by William Wallace and after his execution, led by Robert the Bruce, Elizabeth’s husband. Robert the Bruce as Earl of Carrick and 7th Lord of Annandale, held estates and property in Scotland, a barony and some minor properties in England, and a strong claim to the throne of Scotland

On February 10, 1306, Robert the Bruce and his supporters killed a rival for the throne, John III Comyn, Lord of Badenoch at Greyfriars Church in Dumfries, Scotland. The bad blood between the two men went far back, and they had found it impossible to work together as Guardians of the Realm. Shortly after, Robert and his followers went to Scone, the traditional coronation site of the Kings of Scots. On March 27, 1306, Robert the Bruce was proclaimed Robert I, King of Scots, and the crown was placed on his head by Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan “in the presence and with the consent of four bishops, five earls, and with the consent of the people.” According to tradition, the ceremony of crowning the monarch was performed by a representative of Clan MacDuff.

Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan, crowns Robert the Bruce at Scone in 1306 from a modern tableau at Edinburgh Castle; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

And so Elizabeth de Burgh was now Queen of Scots. However, she did not think she would be queen for long because she feared her husband would be defeated by Edward I. She supposedly said, “Alas, we are but king and queen of the May! ” Both Robert the Bruce and John Comyn had sworn fealty to King Edward I of England. When Edward I heard that John Comyn had been murdered, he vowed “by the God of Heaven and these swans” to avenge Comyn’s death and the treachery of the Scots. On his demand, his knights took a similar oath, and they were sent off to Scotland to seek revenge.

In Scotland, Robert I, King of Scots was already engaged in a civil war with the family and friends of the murdered John Comyn. His coronation had given him some legitimacy, but his position was very uncertain. By the middle of June 1306, the English were in Perth, Scotland, and were joined by supporters of John Comyn. Robert, abiding by the conventions of feudal warfare, invited the English commander to leave the walls of Perth and join him in battle, but the English commander declined to do so. Robert, believing that the English refusal to accept his challenge was a sign of weakness, moved his forces a few miles to nearby Methven, where he made camp for the night. Before dawn on June 19, 1306, Robert’s army was taken by surprise and almost destroyed. Robert barely escaped and fled with a few followers to the Scottish Highlands.

Elizabeth was not so lucky. After the Battle of Methven, under the protection of his brother Niall, Robert sent Elizabeth, his daughter Marjorie from his first marriage, his sisters Mary and Christina and Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan (who had crowned him) to Kildrummy Castle, the seat of the Earls of Mar, the family of his first wife Isabella of Mar. The English besieged Kildrummy Castle and Niall Bruce and all the men of the castle were hanged, drawn, and quartered. However, the women had escaped and sought sanctuary at St. Duthac’s Chapel in Tain, Scotland. The sanctuary was breached by William, Earl of Ross who had the women arrested and handed over to the English.

King Edward I of England sent his hostages to different places in England. Marjorie went to the convent at Watton, Yorkshire and her aunt Christina Bruce was sent to another convent. Marjorie’s aunt Mary Bruce and Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan were imprisoned in wooden cages and exposed to public view. Mary’s cage was at Roxburgh Castle and Isabella’s was at Berwick Castle. Marjorie, Mary, and Christina were finally set free around 1314 – 1315, probably in exchange for English noblemen captured after the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1314. There is no mention of Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan in the records, so she probably died in captivity.

The punishment of Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan

Queen Elizabeth’s punishment was lighter than that of the other women because King Edward I needed the support of her father, the powerful Earl of Ulster. She was imprisoned for eight years by the English and was moved around quite a bit:

After the Scots’ victory at the Battle of Bannockburn where they routed the English in June 1314, Elizabeth was moved to York while prisoner exchange talks took place and where she had an audience with King Edward II of England who had succeeded his father in 1307. Finally, in November 1314, she was moved to Carlisle, close to the Scots border, just before the exchange and her return to Scotland. Because of the turmoil in Scotland and Elizabeth’s imprisonment, Robert and Elizabeth did not have any children until after her return to Scotland in 1314.

Elizabeth and Robert had four children:

- Margaret (born between 1315 and 1323 – 1346), William de Moravia, 5th Earl of Sutherland, had one son John who died of the plague at age 20, Margaret died in childbirth

- Matilda (born between 1315 and 1323 – 1353), married Thomas Isaac, had two daughters

- David II, King of Scots (1324 – 1371), twin of John, married (1) Joan of The Tower, daughter of King Edward II of England, no issue (2) Margaret Drummond, no issue

- John (1324 – 1327), younger twin of David, died young

After falling from her horse, Elizabeth died on October 27, 1327, at Cullen Castle in Banffshire, Scotland, aged about 43-years-old. She was buried at Dunfermline Abbey in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland, the resting place of many Kings and Queens of Scots. Robert I, King of Scots died 18 months later and was buried next to his wife. In 1560, Dunfermline Abbey was sacked by the Calvinists during the Scottish Reformation, and Elizabeth and Robert’s tomb was destroyed. During construction work on the new abbey in 1819, Robert’s coffin was discovered and then Elizabeth’s coffin was rediscovered in 1917. Both coffins were re-interred in the new abbey.

Victorian brass plate covering the tomb of Robert Bruce and Elizabeth de Burgh; Photo Credit – By Otter – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5117548

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Ashley, Michael. British Kings & Queens. 1st ed. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1998. Print.

- “Battle Of Methven”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 3 Apr. 2017.

- Dodson, Aidan. The Royal Tombs Of Great Britain. 1st ed. London: Duckworth, 2004. Print.

- “Elizabeth De Burgh”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 3 Apr. 2017.

- “Richard Óg De Burgh, 2Nd Earl Of Ulster”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 3

- “Robert The Bruce”. En.wikipedia.org. N.p., 2017. Web. 3 Apr. 2017.

- Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.