by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

St. Giles’ Cathedral; Credit – By Carlos Delgado – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35465527

Originally a Roman Catholic church, today St. Giles Cathedral, which this writer has visited, located on the Royal Mile in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland, is a Presbyterian church (Church of Scotland). The founding of St. Giles is usually dated to 1124 and attributed to David I, King of Scots. Construction of the current church began in the 14th century and continued until the early 16th century. During the 19th and 20th centuries, there were major alterations including the addition of the Thistle Chapel, the chapel of the Order of the Thistle. St. Giles Cathedral is associated with many events and persons in Scottish history, notably John Knox (circa 1514 – 1572), a leader of the Scottish Reformation and the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland who as the minister of St. Giles after the Scottish Reformation, delivered fiery sermons from the pulpit.

Below are some royal connections to St. Giles Cathedral.

********************

1437 – A Requiem Mass for James I, King of Scots

James I, King of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

On February 20, 1437, plotters supporting the claim to the throne of Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl, a son of Robert II, King of Scot’s second marriage, broke into the Blackfriars Priory in Perth, Scotland where James I, King of Scots and his wife Joan Beaufort were staying. The conspirators reached the couple’s bedroom where Joan tried to protect James but was wounded. James then tried to escape via an underground passage but was cornered and hacked to death by Sir Robert Graham. There was no strong support for the conspiracy and James’ assassins were soon captured and brutally executed. Although James I was buried in the Carthusian Charterhouse of Perth, which he had founded, a Requiem Mass was said for him at St. Giles Cathedral.

********************

The Royal Pew

The Royal Pew; Credit – By CPClegg – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90158521

Marie of Guise was the second wife of James V, King of Scots, and the mother of Mary, Queen of Scots. In 1548, five-year-old Mary, Queen of Scots set sail for France where she would be raised with her future husband. She would not return to Scotland for thirteen years, after a short-lived marriage due to the early death of her first husband François II, King of France. Mary’s mother Marie remained in Scotland as a member of the Council of Regency and then in 1554, she became Regent of Scotland. There has been a royal loft or royal pew in St. Giles Cathedral since the regency of Marie of Guise. The current royal pew has a tall back and with the royal arms of Scotland standing atop a canopy. It was created for the 1953 visit of Queen Elizabeth II.

********************

1570 – Funeral and Burial of James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, half-brother of Mary, Queen of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (circa 1531 – 1570) was the elder half-brother of Mary, Queen of Scots, the son of James V, King of Scots and his mistress Lady Margaret Erskine. James Stewart became a Protestant as had most of his mother’s family. Left a childless widow by the death of her husband, James’ Roman Catholic half-sister 18-year-old Mary, Queen of Scots returned to Scotland from France in 1561. During Mary’s thirteen-year absence, the Protestant Reformation had swept through Scotland. Despite their religious differences, James Stewart became the chief advisor to his sister and Mary created her half-brother Earl of Moray. Eventually, Mary’s behavior angered even her half-brother and he joined other Protestant lords in a rebellion. In 1567, Mary, Queen of Scots was deposed and succeeded by her infant son James VI, King of Scots. James Stewart, Earl of Moray served as Regent for his infant nephew.

John Knox preaching the funeral sermon of the Earl of Moray, depicted in a stained-glass window at St. Gile’s Cathedral; Credit – By CPClegg – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82436877

On January 23, 1570, in Linlithgow, Scotland, while still serving as Regent for his nephew James VI, King of Scots, the 39-year-old Moray was assassinated by James Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh, a supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots. It was the first assassination by a firearm in recorded history. James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray was buried at St. Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh, Scotland. Seven earls and lords carried his body into the church, and John Knox, the Scottish minister who was a leader of Scotland’s Reformation and the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, preached at the funeral.

Monument to James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray at St. Giles Cathedral; Credit – By CPClegg – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82436880

********************

1590 – Service of Thanksgiving for Anne of Denmark, Queen of Scots

Anne of Denmark, Queen of Scots, Queen of England; Credit – Wikipedia

James VI, King of Scots, the son of Mary, Queen Scots, was ready to marry to provide an heir to the throne of Scotland. In Denmark, Princess Anne, daughter of King Frederik II of Denmark, found that candidates for her hand in marriage were numerous as the Danish court was considered wealthy and a high dowry was expected. Anne’s mother Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, who conducted the marriage negotiations after the death of her husband in 1588, opted for King James VI. On August 20, 1589, Anne was married by proxy to James VI, King of Scots at Kronborg Castle in Helsingør, Denmark.

Ten days after the proxy wedding, Anne set sail for Scotland, but severe storms forced her to land in Norway. Upon hearing this, James set sail to personally bring Anne to Scotland. On November 23, 1589, the couple was formally married at the Bishop’s Palace in Oslo, Norway. After a prolonged visit to Denmark, James and Anne landed in Scotland on May 1, 1590. On May 15, 1590, Anne made her state entry into Edinburgh.

After such a long and sometimes dangerous ordeal, a service of thanksgiving was held at St. Giles Cathedral. Anne entered St. Giles under a red velvet canopy while the choir sang Psalm 19 “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows his handiwork.” Robert Bruce of Kinnaird, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, preached a sermon on Psalm 107, a reflection of thanksgiving for the safe return of those on the sea: “Those who go down to the sea in ships, who do business on great waters.”

********************

1633 – Visit of Charles I, King of England, King of Scots

Charles I, King of England, King of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1603, James VI, King of Scots succeeded Queen Elizabeth I of England and was then also King James I of England. His son and successor Charles I, King of England, King of Scots had been born at Dunfermline Palace in Fife, Scotland. Although Charles was crowned at Westminster Abbey on February 2, 1626, the Scots insisted that he should also be crowned in his northern kingdom. The coronation took place at the Palace of Holyrood in Edinburgh on June 18, 1633, during an elaborate and extravagant royal tour of Scotland. The crown, sword, and scepter used in the coronation date from the late 15th and early 16th centuries, and were first brought together for the coronation service of the nine-month-old Mary, Queen of Scots. On June 23, 1633, Charles I made an unannounced visit to St. Giles Cathedral and displaced the Church of Scotland clergy with his own clergy who conducted the service according to the rites of the Church of England.

********************

1822 – King George IV visits Scotland

King George IV during his 1822 trip to Scotland; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1822, King George IV of the United Kingdom’s 21-day visit to Scotland, organized by author Sir Walter Scott, was the first by a British monarch since the reign of King Charles II. On his trip to Scotland, George IV frequently wore a kilt and this helped to make the traditional garb of Highland Scotland popular during the 19th century. During his visit, King George IV attended services at St. Giles Cathedral. The publicity of his visit created the motivation for the city council to fund much-needed renovations on St. Giles Cathedral.

********************

1953 – Queen Elizabeth II receives the Honours of Scotland

Queen Elizabeth II returning the crown of the Honours of Scotland to the care of the Duke of Hamilton, in St. Giles’ Cathedral, Edinburgh, during the Scottish National Service of Thanksgiving and Dedication.

The Honours of Scotland, also known as the Scottish Crown Jewels, date from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and are the oldest surviving set of crown jewels of the United Kingdom. They were first used together as coronation regalia at the coronation of the nine-month-old Mary, Queen of Scots in 1543, and subsequently at the coronations of her infant son James VI in 1567 at Stirling Castle, her grandson Charles I in 1633 at Holyrood Palace, and her great-grandson Charles II in 1651 at Scone.

Embed from Getty Images

The crown (1540), the scepter (circa 1494), and the sword of state (1507) are the three main Honours of Scotland. During her first visit to Scotland after her coronation, Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom received the Honours of Scotland at a National Service of Thanksgiving and Dedication at St. Giles Cathedral on June 24, 1953. During the service, the Honours of Scotland were formally presented to Queen Elizabeth II by Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton. The Queen then returned them to the Duke of Hamilton. The Duke of Hamilton is the senior dukedom in the Peerage of Scotland and the Hereditary Bearer of the Crown of Scotland. The Honours of Scotland are on display in the Crown Room at Edinburgh Castle.

********************

2022 – The Coffin of Queen Elizabeth II lies in rest

The coffin of Queen Elizabeth II lies at rest at St. Giles Cathedral as her four children stand in vigil

Because Queen Elizabeth II died at her Scottish home Balmoral Castle, her funeral plans incorporated Operation Unicorn, the contingency plans for the death of The Queen in Scotland. Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin rested in the ballroom at Balmoral Castle in Scotland where she died on September 8, 2022. On September 11, 2022, her coffin traveled by hearse from Balmoral Castle to the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Upon arrival at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the coffin rested in the palace’s Throne Room. On the afternoon of September 12, 2022, Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin traveled by a procession from the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, Scotland, the short distance up the Royal Mile to St. Giles Cathedral, accompanied by King Charles III and members of the Royal Family. Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin rested in St. Giles Cathedral where members of the public were able to view the coffin. On the evening of September 12, 2022, King Charles III and members of the Royal Family held an evening vigil at St Giles Cathedral. The coffin departed St. Giles Cathedral on September 13, 2022, and traveled by plane to London.

********************

Order of the Thistle

Insignia of a Knight of the Order of the Thistle; Credit – Wikipedia

The Order of the Thistle is Scotland’s senior order and the second-highest order within the United Kingdom. Membership is limited to the Sovereign and sixteen members. In addition, members of the Royal Family and foreign sovereigns can be appointed as Extra Knights and Ladies. Queen Elizabeth II altered the statutes of the order in 1987 allowing women to be admitted as Ladies of the Thistle. Members are appointed in recognition of their public service, contributions to national life, or personal service to the Sovereign. Like the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle is awarded at the sole discretion of the Sovereign. New members are traditionally announced on St. Andrew’s Day, November 30. During the Sovereign’s visit in June or July each year, a service for the Order is held at the Thistle Chapel at St Giles’ Church in Edinburgh, at which point any new members are installed.

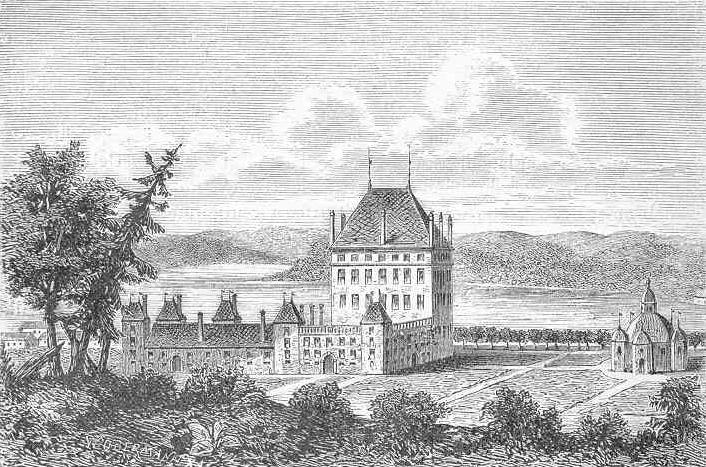

Holyrood Abbey after its designation as the Chapel of the Order of the Thistle in 1687 and before the interior’s destruction in 1688; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1687, James VII, King of Scots (also James II, King of England) founded the Order of the Thistle and designated the Abbey Church at Holyrood Palace, where a Presbyterian congregation worshipped, to be the chapel of the new order. The Abbey Church was converted into a Catholic chapel, as James had converted to Roman Catholicism. A new church, the nearby Canongate Kirk, replaced the Abbey Church as the local Presbyterian parish church. In 1688, the Abbey Church was ransacked by a mob, furious with King James’ Roman Catholic allegiance. The Order of the Thistle was left without a chapel until the Thistle Chapel was added to the nearby St. Giles’ Cathedral in 1911.

Thistle Chapel; Credit – Wikipedia

Over the years, unsuccessful multiple proposals were made either to refurbish Holyrood Abbey for the Order of the Thistle or to create a new chapel at St Giles’ Cathedral. In 1906, the sons of Ronald Leslie-Melville, 11th Earl of Leven donated £24,000 from their father’s estate towards the endowment and the construction of a Thistle Chapel on the south side of St. Giles Cathedral. The Thistle Chapel was formally opened by King George V on July 19, 1911.

Swords, helms and crests of Knights of the Thistle above their stalls in the Thistle Chapel; Credit – By Philip Allfrey – Taken by the author, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=935442

This author has visited the Thistle Chapel and can verify that it is relatively small – 7.6 meters (25 feet) long and 4.3 meters (14 feet) wide. Each member, including the Sovereign, has a stall in the Thistle Chapel, above which his or her heraldic devices are displayed.

Stall plates of Knights of the Thistle; Credit – By Philip Allfrey – Taken by the author, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=935427

Enameled plates with the name, arms, and date of admission of members, living and deceased, who have sat in each stall are attached to the back of the stall. Unlike the Order of the Garter, the banners of Knights and Ladies of the Thistle are not hung in the chapel but instead in an adjacent part of St Giles Cathedral.

Banners of Knights of the Thistle, hanging in St Giles Cathedral; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Stewart,_1st_Earl_of_Moray> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. St Giles’ Cathedral – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Giles%27_Cathedral> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Order of the Thistle – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_the_Thistle> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Thistle Chapel – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thistle_Chapel> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- Flantzer, S., 2016. Anne of Denmark, Queen of Scots, Queen of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/anne-of-denmark-queen-of-scots-queen-of-england/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2020. Assassination of James I, King of Scots (1437). [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/assassination-of-james-i-king-of-scots-1437/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. King Charles I of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-charles-i-of-england/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2015. King George IV of the United Kingdom. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-george-iv-of-the-united-kingdom/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2020. Lady Margaret Erskine, Mistress of James V, King of Scots. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/lady-margaret-erskine-mistress-of-james-v-king-of-scots/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- Mehl, Scott, 2012. British Orders and Honours. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/current-monarchies/british-royals/british-orders-and-honours/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- St GILES’ CATHEDRAL. 2021. St GILES’ CATHEDRAL. [online] Available at: <https://stgilescathedral.org.uk/> [Accessed 22 May 2021].

- The Royal Family. 2021. The Honours of Scotland. [online] Available at: <https://www.royal.uk/honours-scotland> [Accessed 22 May 2021].