by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

Drawing of William Longespée from his effigy in Salisbury Cathedral; Credit – Wikipedia

Born circa 1176, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury was the illegitimate son of King Henry II of England and his former royal ward and then mistress Ida de Tosny. His surname Longespée probably refers to William’s height and the oversized weapons he used. William’s paternal grandparents were Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine and Empress Matilda, Lady of the English, the only surviving legitimate child of King Henry I of England. His maternal grandparents were Ralph de Tosny, V, Lord of Flamstead (in Hertfordshire, England) and Margaret de Beaumont. Henry II had several long-term mistresses and around twelve illegitimate children, William’s half-siblings.

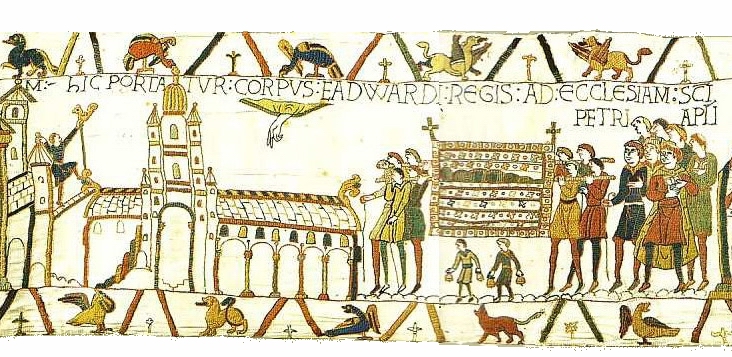

13th-century depiction of William’s royal half-siblings, (l to r) William, Young Henry, Richard, Matilda, Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, and John; Credit – Wikipedia

William had eight royal half-siblings from his father’s marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine:

- William IX, Count of Poitiers (1153 – 1156), died in childhood

- Henry the Young King (1155 – 1183), married Marguerite of France, no children

- Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria (1156 – 1189), married Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, had five children, including Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- King Richard I of England (1157 – 1199), married Berengaria of Navarre, no children

- Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany (1158 – 1186), married Constance, Duchess of Brittany, had three children

- Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile (1162 – 1214), married King Alfonso VIII of Castile, had twelve children including King Enrique I of Castile; Berengaria, Queen Regnant of Castile and Queen of León; Urraca, Queen of Portugal; Blanche, Queen of France, and Eleanor, Queen of Aragon

- Joan of England, Queen of Sicily (1165 – 1199), married (1) King William II of Sicily, no surviving children (2) Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, had two children, Joan died in childbirth with her third child who also died

- King John of England (1166 – 1216), married 1) Isabella, 3rd Countess of Gloucester, marriage annulled, no children (2) Isabella, Countess of Angoulême; had five children, including King Henry III of England; Joan of England, Queen of Scots, and Isabella of England, Holy Roman Empress

William’s mother Ida de Tosny married Roger Bigod, 2nd Earl of Norfolk and the couple had at least eight children, William’s half-siblings:

- Margery Bigod (1174 – 1237), married William de Hastings, Steward to King Henry II, had at least two children

- Hugh Bigod, 3rd Earl of Norfolk (circa 1182 – 1225), married Maud Marshal, had four children

- Mary Bigod (1188 – 1237), married Ranulf FitzRobert, 4th Lord Middleham and Spennithorne, had at least one son

- William Bigod (circa 1188 – ?), married Margaret de Sutton

- Roger Bigod (1198 – 1230)

- Ralph Bigod (circa 1201 – circa 1214), died in childhood

- John Bigod

- Ida Bigod

William’s father King Henry II of England; Credit – Wikipedia

King Henry II acknowledged William as his son but little is known about William’s childhood. According to William’s own statements, he grew up at times with Hubert de Burgh, later Earl of Kent and Chief Justiciar of England and Ireland during the reigns of King John and his son and successor King Henry III. In 1188, when William came of age, his father gave him the town of Appleby in Lincolnshire, England.

In 1196, William married a great heiress Ela of Salisbury, 3rd Countess of Salisbury, the only child of William FitzPatrick, 2nd Earl of Salisbury, and Eléonore de Vitré. Earlier in 1196, Ela’s father died and she succeeded to her father’s title as 3rd Countess of Salisbury in her own right. After the marriage, William became the 3rd Earl of Salisbury by Jure uxoris, by right of his wife. Because Ela was only eleven years old, the couple did not have children for several years.

William and Ela had at least nine children:

- Ida Longespée (circa 1205 – 1269), married (1) Ralph de Somery of Dudley, no children (2) William de Beauchamp, Baron of Bedford, had seven children

- Isabella Longespée (circa 1208 – 1268), married William de Vesci, no children

- William Longespée the Younger (circa 1209 – 1250), married Idoine de Camville, had four children, killed during the 7th Crusade

- Mary Longespée (1209 – 1262), married Sir Robert de Ros, 1st Baron Warke, had five children

- Petronella Longespée (1209 – ?), a nun

- Richard Longespée (circa 1214 – ?), Clerk and Canon at Salisbury Cathedral

- Stephen Longespée, Seneschal of Gascony and Justiciar of Ireland (circa 1216 – 1260), married Emmeline de Riddlesford, had two daughters

- Ela Longespée (circa 1217 – 1298), married (1) Thomas de Beaumont, 6th Earl of Warwick, no children; married (2) Philip Basset, no children

- Nicholas Longespée, Bishop of Salisbury (circa 1218 – 1297)

Effigy of William’s half-brother King Richard I; By Adam Bishop – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17048652

William participated in the campaigns (1193 – 1198) of his half-brother King Richard I of England in the Duchy of Normandy (now in France) to recover the land seized by King Philippe II of France while Richard was participating in the Third Crusade. William was closest in age to King John, the youngest of his father’s legitimate children, who succeeded to the English throne in 1199. During King John’s reign, William was at court on important ceremonial occasions and held several positions: High Sheriff of Wiltshire, Lieutenant of Gascony, Constable of Dover, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, Lord Warden of the Welsh Marches, and Sheriff of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire.

Effigy of William’s half-brother King John; Credit – Wikipedia

William was a commander during the 1210 – 1212 Welsh and Irish campaigns of his half-brother King John of England and participated in the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. In 1213, he led the English fleet in the Battle of Damme in which the English seized or destroyed a good portion of the French fleet. On July 27, 1214, William commanded the right flank of an English coalition army against France at the Battle of Bouvines, the last battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. The battle ended in defeat for the English coalition and capture for William when the priest-soldier Philippe de Dreux, Bishop of Beauvais threw a mace at his head. William was unhorsed and taken prisoner and the English soldiers fled. Because of the resounding French victory, all the Norman and Angevin French ancestral territories, Normandy, Maine, Touraine, Anjou, and Poitou, were lost forever to the English crown.

While King John was trying to save his French territories, his discontented English barons led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, were protesting John’s continued misgovernment of England. The result of this discontent was the best-known event of John’s reign, the Magna Carta, the “great charter” of English liberties, forced from King John by the English barons and sealed at Runnymede near Windsor Castle on June 15, 1215. Among the liberties were the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown.

William had returned to England during King John’s troubles with the English barons and was one of the few barons who was loyal to John. Infuriated by being forced to agree to the Magna Carta, John turned to Pope Innocent III, who declared the Magna Carta null and void and the rebel barons excommunicated. The conflict between John and the barons was transformed into an open civil war, the First Barons’ War (1215 – 1217). William was one of the leaders of King John’s army in the south of England. However, the rebel barons appealed to King Philippe II of France, and offered his son, the future King Louis VIII of France, the English crown. After Louis of France landed in England as an ally of the rebel barons, William went over to the rebel side because he thought John’s cause was lost.

William’s half-brother King John died of dysentery on October 19, 1216. He was succeeded by his nine-year-old son King Henry III of England. The First Barons’ War continued after King John’s death, but the great William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, who served four English kings – Henry II, Richard I, John, and Henry III – managed to get most barons to switch sides from Louis of France to the new King Henry III and attack Louis. The Magna Carta was reissued in King Henry III’s name with some of the clauses omitted and was sealed by the nine-year-old king’s regent William Marshal. William Longespée supported his nephew King Henry III and held an influential place in the government during the young king’s minority.

William’s tomb in Salisbury Cathedral; Credit – By Bernard Gagnon – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7140363

In 1225, returning to England from Gascony (now in France), William was shipwrecked off the coast of Brittany (now in France). He spent several months in a monastery on the French island of Île de Ré. Shortly after returning to England, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, aged about fifty, died on March 7, 1226, at his home, Salisbury Castle in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England which was part of Old Sarum and no longer exists. He was buried at Salisbury Cathedral where he had laid the foundation stones in 1220.

William’s wife Ela never remarried. Three years after William’s death, Ela founded Lacock Abbey in Lacock, Wiltshire, England. In 1238, she entered Lacock Abbey as a nun and was Abbess from 1240 – 1257. Ela survived her husband William by thirty-five years, dying on August 24, 1261, aged about seventy-three, and was buried in Lacock Abbey.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Ashley, Mike. (1998). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. Carroll & Graf Publishers.

- Flantzer, Susan. (2016). King Henry II of England. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-henry-ii-of-england/

- Flantzer, Susan. (2016). King John of England. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-john-of-england/

- Ida De Tosny, Countess of Norfolk. geni_family_tree. (2022). https://www.geni.com/people/Ida-de-To%C3%ABny-Countess-of-Norfolk/6000000006428477266

- Weir, Alison. (2008). Britain’s Royal Families – The Complete Genealogy. Vintage Books.

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Ela of Salisbury, 3rd Countess of Salisbury. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ela_of_Salisbury,_3rd_Countess_of_Salisbury

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Ida de Tosny. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_de_Tosny

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). William Longespée, 3. Earl of Salisbury. Wikipedia (German). https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Longesp%C3%A9e,_3._Earl_of_Salisbury

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2024). William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Longesp%C3%A9e,_3rd_Earl_of_Salisbury

- William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury. geni_family_tree. (2023). https://www.geni.com/people/William-Longesp%C3%A9e-3rd-Earl-of-Salisbury/6000000006232319371