by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2020

Detail of Ford Madox Brown’s painting depicting Alice Perrers and King Edward III (see full painting below); Credit – Wikipedia

Alice Perrers is the most famous English royal mistress between King Henry II’s Rosamund de Clifford and King Edward IV’s Jane Shore. Biographical information about Alice Perrers is sketchy but recent research by historians Mark Ormrod and Laura Tompkins has revealed new details about her early life.

Alice Perrers was born around 1340 in London, England. Her family’s surname was Salisbury and they worked as goldsmiths. Janyn Perrers, who would become Alice’s first husband, became an apprentice to the Salisbury family in 1342. Goldsmiths would have been somewhat well-to-do and Alice most likely received an education at home and attended a local girls school.

Janyn Perrers eventually became a full member of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths of London. It appears that around 1359, he did some work for the royal court because in a royal writ he is described as “our beloved Janyn Perrers, our jeweler”. There is a possibility that he met King Edward III in his capacity as a goldsmith and jeweler and that Alice may have accompanied him. Around this same time, Alice and Janyn were married. The research shows that Janyn Perrers died sometime between May 19, 1361 and May 18, 1362.

Coronation of Philippa of Hainault; Credit – Wikipedia

Shortly after her husband’s death, Alice became a lady-in-waiting to Philippa of Hainault, the wife of King Edward III. Even if Alice had not previously met Edward III, they certainly became acquainted while she served as a lady-in-waiting. Alice, who was about 24-years-old, gave birth to the first of her three children by Edward III in 1364, when the king was 56-years old.

Alice and Edward III’s children:

- Sir John de Southeray (1364 – 1383), married Maud Percy, daughter of Henry de Percy, 3rd Baron Percy, no children

- Jane (1365 – ?), married Richard Northland

- Joan (1366 – before 1431), married Robert Skerne

Edward III’s relationship with Alice was kept mostly secret until the death of his wife in 1369. After Queen Philippa’s death, Edward III became increasingly dependent upon Alice. While the government was at Westminster Palace and his household was at Windsor Castle, Edward spent much of his time isolated at Havering Palace, Sheen Palace, and Eltham Palace. Alice became his chief advisor. She made sure she put in good words for her ambitious friends. Eventually, Alice and her relationship with the King of England caused much gossip at Westminster and Windsor.

Alice acquired numerous gifts from Edward III, including some of Queen Philippa’s jewelry, and she soon became an extremely wealthy woman. Her fortune was worth more than £20,000, equal to £6,000,000 in today’s money. On Edward’s command, Alice dressed in golden garments and was paraded around London as “The Lady of the Sun”. Courtiers were expected to behave respectfully toward her. This caused great criticism from those at court and eventually from the public. Alice was seen as an ambitious, grasping, calculating, and cold-hearted opportunist who manipulated the elderly, aging King Edward III.

Although Alice had received gifts from the king, her financial success cannot be totally attributed to that. Perhaps it was from having a father and a husband who were successful goldsmiths, but Alice did possess business acumen and did have useful business connections through the court. At the height of her power, Alice controlled 56 manors and castles in England and only fifteen were royal gifts.

Worried about Edward III’s advancing age and that after his death she would no longer have his protection, in November 1375, Alice made a secret marriage to Sir William Windsor, 1st Baron Windsor who was 26 years older than Alice. Because William was the Royal Lieutenant in Ireland, he was often away and this lessened the chance that Edward III would find out about the secret marriage. William and Alice had no children and remained married until William died in 1384.

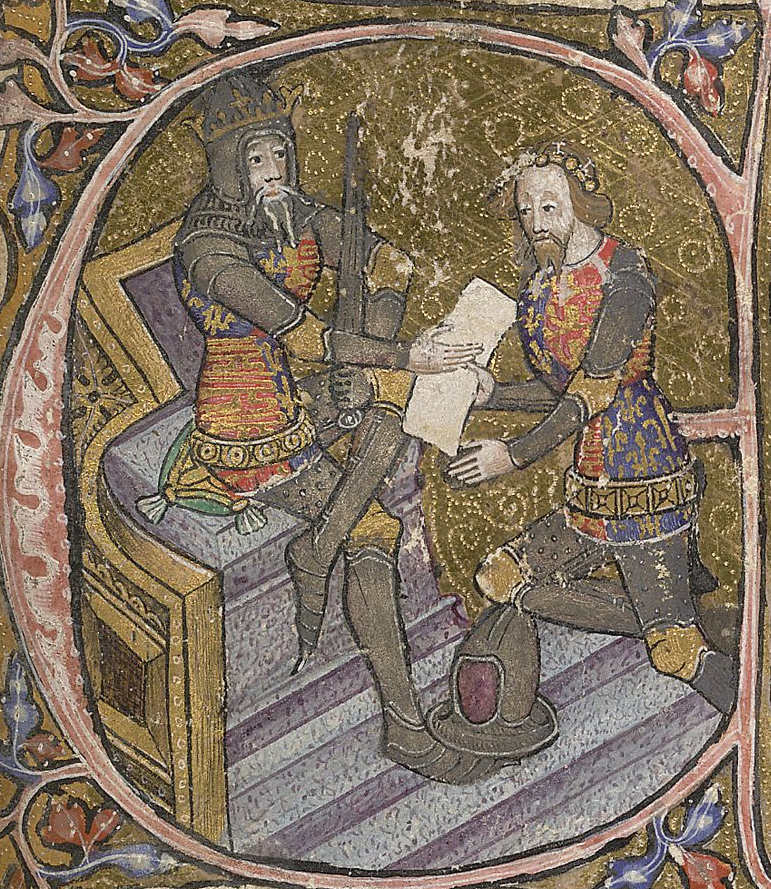

King Edward III and his eldest son Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales; Credit – Wikipedia

Because the English court was perceived by much of the English population to be corrupt, the English Parliament met from April 28 to July 10, 1376, in an effort to reform the Royal Council. The Good Parliament was the name history has assigned to this meeting. Meanwhile, King Edward III’s eldest son and heir, Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, was dying. He summoned to his bedside, his father King Edward III and John of Gaunt, Edward III’s third but second surviving son, and made them swear to recognize his nine-year-old son, the future King Richard II, as Edward III’s successor. Both Edward III and John of Gaunt swore to recognize Richard, and soon after Parliament summoned Richard and acknowledged him as heir to the throne. Edward the Black Prince died on June 8, 1376.

As a result of the Good Parliament’s actions, Richard Lyons, Warden of the Mint, and William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer, Chamberlain of the Household, who were believed to be robbing the treasury, were called before Parliament, impeached, and then imprisoned. Also, King Edward III’s mistress, Alice Perrers, was called to Parliament where she was tried for corruption, banished from England, and her lands were forfeited. Parliament then imposed a new set of councilors on King Edward III. However, by the autumn of 1376, John of Gaunt was working on undoing the Good Parliament’s work. He dismissed the new council and recalled Lyons and Latimer to the Royal Council and Alice Perrers was recalled to court and regained some of her lands.

King Edward III suffered a stroke in May 1377. He died at Sheen Palace in Richmond, England on June 21, 1377, at the age of 64 with his mistress Alice Perrers at his side.

Geoffrey Chaucer reading at the court of Edward III by Ford Madox Brown, painted 1847–1851; Alice and Edward III are in the upper right; Credit – Wikipedia

Alice had a great influence on the poet Geoffrey Chaucer and supported him financially. She is thought to be the model for the Wife of Bath in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Alice Perrers died in Gaynes Park, Upminster, England during the winter of 1400/1401 at around the age of 60. She was buried in either the church or the churchyard of the Church of St Laurence, Upminster but there is no memorial to mark her grave. Her property was left to her surviving children, her daughters Jane and Joan.

Church of St Laurence, Upminster; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Alice Perrers. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Perrers> [Accessed 22 July 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2015. King Edward III Of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-edward-iii-of-england/> [Accessed 22 July 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2020. Alice Perrers. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Perrers> [Accessed 22 July 2020].

- Medievalists.net. 2016. Alice Perrers – The Story Of A King’s Mistress. [online] Available at: <https://www.medievalists.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/the-medieval-magazine-no51.pdf> [Accessed 22 July 2020].

- Mortimer, Ian, 2014. Edward III: The Perfect King. New York: Rosetta Books LLC.