by Emily McMahon and Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

On floor: Tsarevich Alexei; Seated: Grand Duchess Maria, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Emperor Nicholas II, Grand Duchess Anastasia; Standing: Grand Duchess Olga, Grand Duchess Tatiana – 1913; Credit – Wikipedia

The Execution

Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia, his wife Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, their five children, along with three of their most loyal servants and the court doctor, were shot to death by firing squad on July 17, 1918.

-

- Unofficial Royalty: Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia

- Unofficial Royalty: Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (Empress Alexandra Feodorovna)

- Unofficial Royalty: Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia, Grand Duchesses of Russia

- Unofficial Royalty: Tsesarevich Alexei Nikolaevich of Russia

- Wikipedia: Dr. Eugene Botkin (court doctor)

- Wikipedia: Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov (cook)

- Wikipedia: Alexei Yegorovich Trupp (footman)

- Wikipedia: Anna Stepanovna Demidova (maid)

Ivan Mikhailovich Kharitonov; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

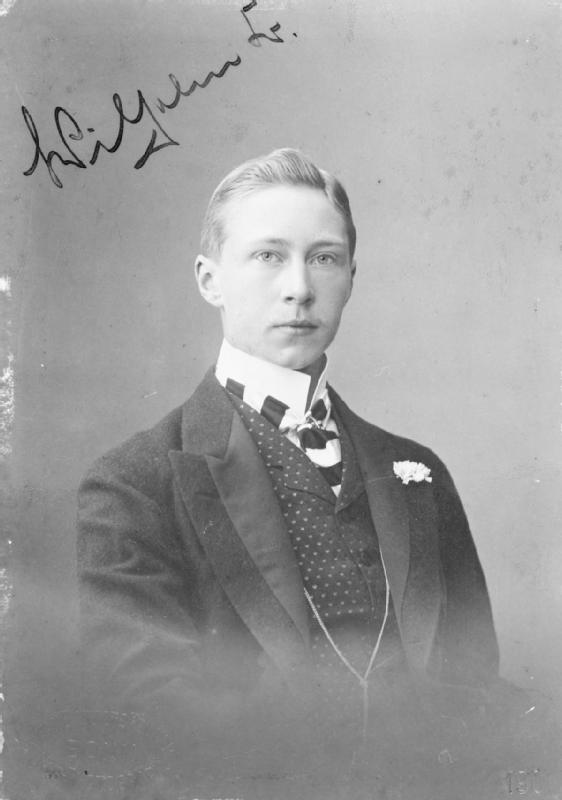

Alexei Yegorovich Trupp; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Anna Stepanovna Demidova; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

The family had been in exile in the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, Siberia, Russia since the previous spring. The residence was also known as The House of Special Purpose, as the Bolsheviks had wanted to bring Nicholas to trial eventually.

At the time of the family’s execution, the Bolshevik Red Army controlled Yekaterinburg with the anti-communist White Army gaining strength in the surrounding area. Additionally, Czechoslovak troops were also gaining on the city but (unknown to Red Army forces) this was to protect the Trans-Siberian Railway rather than the imperial family. To prevent the family from possible escape into White Army hands, the decision was made to execute them.

The family doctor, Eugene Botkin, awoke the family around midnight on July 17, urging them to dress quickly. All seven of the Romanov family plus Botkin and three servants (maid Anna Demidova, cook Ivan Kharitonov, and footman Alexei Trupp) were escorted to a basement room. Anastasia also took the family dog. Chairs were brought in for Nicholas, Alexandra, and Alexei. The family believed they were being evacuated to a new location.

Eight members of the firing squad entered the basement room along with Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of the Ipatiev House. A few minutes later Yurkovsky informed the prisoners that they were about to be executed. Nicholas arose in shock but was quickly shot down. Chaos ensued as the executioners gunned down the family members and their servants.

Alexandra and her daughters had sewn jewels into their clothing to provide money if the family was sent into exile and these jewels acted for a time as shields against the bullets. Anna Demidova carried a pillow also sewn with jewels. Eventually, the soldiers brought out bayonets to kill the last remaining survivors. After several minutes of ricocheting bullets and stabbings, all eleven members of the party were dead. Vladimir Lenin had ordered the assassination.

After much debate and multiple vehicle problems, the bodies were taken to a remote site north of Yekaterinburg. The initial plan was to burn the bodies but when this took longer than expected, the remaining bodies were buried in an unmarked pit. Acid was poured on the corpses, the bodies were covered with railroad ties, and the pit was smoothed over with dirt and ash.

The murder of the imperial family shocked Russia and the world. The ensuing Soviet regime and the considerable length of time between the executions and the discovery of their bodies gave way to many different legends of the survival of at least one of the family members. Many different people claimed to be Alexei or one of his sisters in the 1920s and 1930s, the best known of which was Anna Anderson who was later proven to be a Polish woman.

Discovery of Remains and Burial

In 1934, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of the Ipatiev House, produced an account of the execution and disposal of the bodies. His account later matched the remains of nine bodies found north of Yekaterinburg in 1991. In 1994, when the bodies of the Romanovs were exhumed, two were missing – one daughter, either Maria or Anastasia, and Alexei. The remains of the nine bodies recovered were confirmed as those of the three servants, Dr. Botkin, Nicholas, Alexandra, and three of their daughters. The remains of Olga and Tatiana were identified based on the expected skeletal structure of young women of their age. The remains of the third daughter were either Maria or Anastasia.

Icon of the Romanov Family; Credit – By Aliksandar – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45616224

The family and their servants were canonized as new martyrs in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in 1981, and as passion bearers in the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000. The formal burial of Nicholas, Alexandra, Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia, Dr. Botkin, and the three servants took place on July 17, 1998, the 80th anniversary of their deaths, in St. Catherine Chapel at the Peter and Paul Cathedral in Saint Petersburg which this author has visited. Boris Yeltsin, President of Russia, many Romanov family members, and family members of Dr. Botkin and the servants attended the ceremony. Prince Michael of Kent represented his first cousin Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. Three of Prince Michael’s grandparents were first cousins of Nicholas II.

- YouTube: Romanov Funeral (the video will go automatically to the next part)

St. Catherine’s Chapel at the Peter and Paul Cathedral; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Until 2009, it was not entirely clear whether the remains of Maria or Anastasia were missing. On August 24, 2007, a Russian team of archaeologists announced that they had found the remains of Alexei and his missing sister in July 2007. In 2009, DNA and skeletal analysis identified the remains found in 2007 as Alexei and his sister Maria. In addition, it determined that the royal hemophilia was the rare, severe form of hemophilia, known as Hemophilia B or Christmas disease. The results showed that Alexei had Hemophilia B and that his mother Empress Alexandra and his sister Grand Duchess Anastasia were carriers of the disease. The remains of Alexei and Maria have not yet been buried. The Russian Orthodox Church has questioned whether the remains are authentic and blocked the burial.

- New York Times: Russian Orthodox Church Blocks Funeral for Last of Romanov Remains (Susan is a New York Times subscriber and has shared this article so all can read it.)

- Wikipedia: Execution of the Romanov Family

- Alexander Palace Time Machine: Murder of the Imperial Family – The executioner Yurovsky’s account

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.