by Scott Mehl

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Prince Maximilian of Baden was the heir to the throne of the Grand Duchy of Baden, and served briefly as Chancellor of the German Empire.

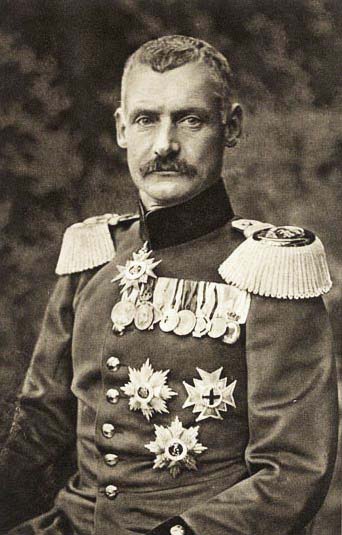

Prince Maximilian of Baden, Margrave of Baden – photo: By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R04103 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5367974

Prince Maximilian Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm of Baden was born in Baden-Baden on July 10, 1867. He was the only son of Prince Wilhelm of Baden (a younger son of Grand Duke Leopold of Baden), and Princess Maria Maximilianovna of Leuchtenburg (a granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia). Max had one older sister:

- Princess Marie of Baden (1865) – married Friedrich II, Duke of Anhalt, no issue

After his initial education, Max studied law and cameralism at Leipzig University before training as an officer in the Prussian Army. In 1907, upon the death of his uncle, Grand Duke Friedrich I of Baden, Max became heir-presumptive to his childless cousin, Friedrich II. In addition to his new position, he became President of the upper house of parliament in Baden. Four years later, he left the Prussian army with the rank of Major General.

Prince Max with his wife and children, c.1910. source: Wikipedia

On July 10, 1900, in Gmunden, Austria, Max married Princess Marie Luise of Hanover. She was the daughter of Ernst August, Crown Prince of Hanover and Princess Thyra of Denmark. The couple had two children:

- Princess Marie Alexandra of Baden (1902 – 1944) – married Prince Wolfgang of Hesse, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, no issue

- Prince Berthold of Baden, Margrave of Baden (1906 – 1963) – married Princess Theodora of Greece and Denmark, had issue

Max returned to military service in 1914 at the beginning of World War I, serving as a general staff member, representing his cousin Friedrich II. However, he soon retired due to ill health. He became honorary president of Baden’s chapter of the German Red Cross, using his family connections to help prisoners of war. Staunchly liberal, he remained out of politics but spoke out against military policies he disagreed with. Despite maintaining a relatively low profile, it was through his friendship with Kurt Hahn that Max would later be appointed Chancellor of Germany. He was initially considered for the job in July 1917, and once again in September 1918 but was turned down by Kaiser Wilhelm II. However, later that same month, when it was clear that the German front was soon to fall, the entire cabinet of Chancellor Georg von Hertling resigned. Von Hertling himself recommended Prince Max to succeed him. This time the Kaiser agreed, and Max was formally appointed on October 3, 1918.

Just a month later, it was clear that the German Empire was ending. At noon on November 9, 1918, Prince Max announced Kaiser Wilhem II’s abdication and the formal renunciation of the Crown Prince. Max also resigned as Chancellor. Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the SPD, asked Max to remain in Berlin as Regent, but Max refused and returned to Baden.

With no further role in politics, Prince Max retired to Baden. He wrote and published several books, and in 1920, he helped Kurt Hahn establish the Schule Schloss Salem , a boarding school in Salem, Germany, later attended by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the brother of his son’s wife.

On August 9, 1928, the last reigning Grand Duke of Baden, Friedrich II, died, and Max became the pretender to the former throne and the Head of the House of Zähringen. At that time, he assumed the historic title of Margrave of Baden. Just over a year later, on November 6, 1929, Prince Max, Margrave of Baden died of kidney failure following several strokes. He is buried in the Mimmenhausen Cemetery in Salem.

* * * * * * * * * *

Baden Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Grand Duchy of Baden Index

- Profiles: Grand Dukes and Consorts of Baden

- Baden Royal Burial Sites

- Baden Royal Dates

* * * * * * * * * *

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.