by Scott Mehl © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Kingdom of Württemberg: Württemberg was a County, a Duchy, and an Electorate before becoming a Kingdom in 1806. At the end of 1805, in exchange for contributing forces to France’s armies, Napoleon, Emperor of the French recognized Württemberg as a kingdom, with Elector Friedrich formally becoming King Friedrich I on January 1, 1806. The reign of Wilhelm II, the last King of Württemberg, came to an end in November 1918, after the fall of the German Empire led to the abdications of all the ruling families. Today the land that encompassed the Kingdom of Württemberg is located in the German state of Baden-Württemberg.

********************

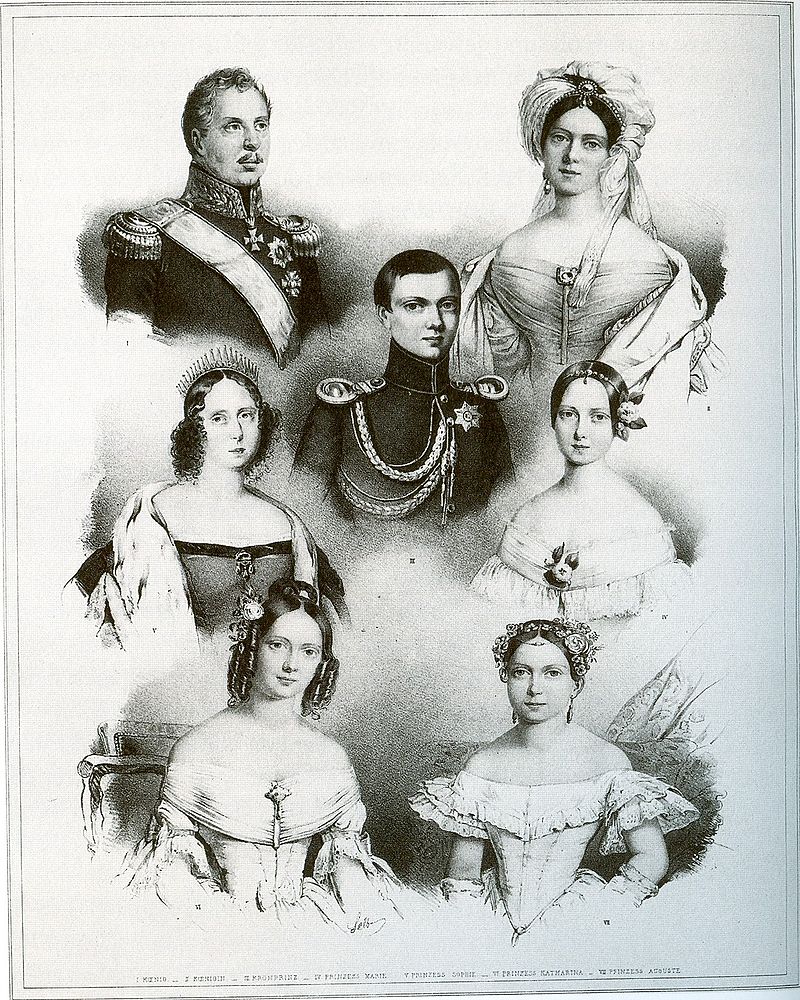

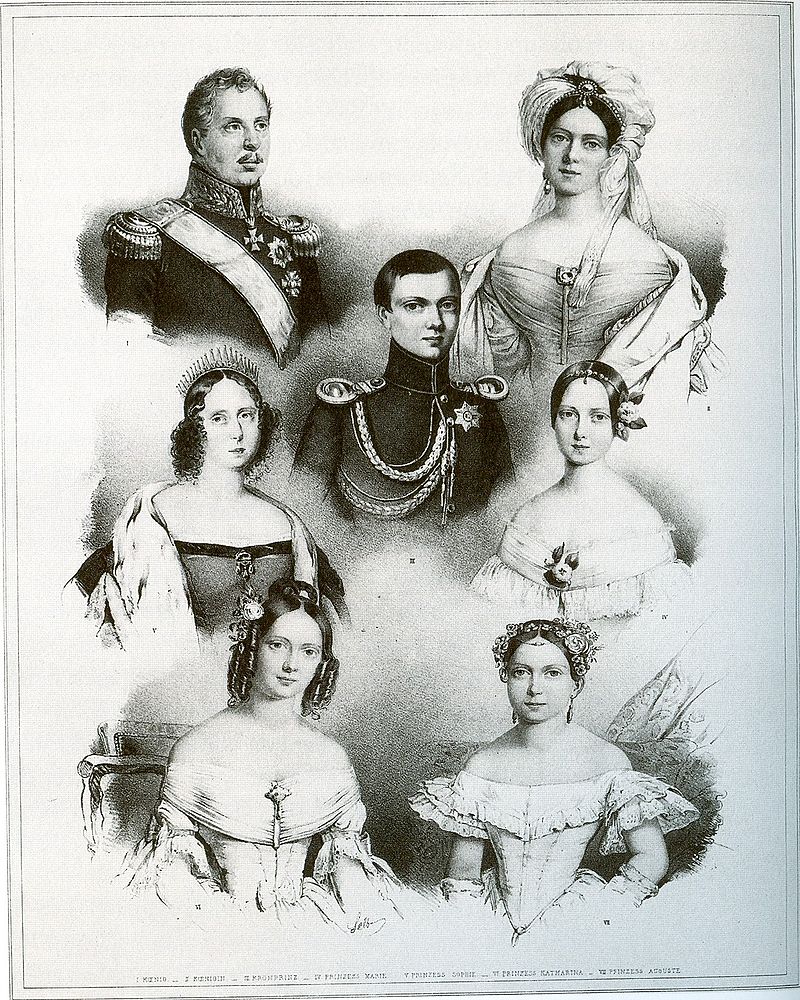

King Wilhelm I of Württemberg; Credit – Wikipedia

King Wilhelm I of Württemberg reigned from 1816 until he died in 1864. He was born Friedrich Wilhelm Karl (known as Fritz) on September 27, 1781, in Lüben, Kingdom of Prussia, now Lubin, Poland, to the future King Friedrich I of Württemberg and his wife Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He had three siblings:

Fritz’s early years were spent in Russia, where his father served as Governor-General of Eastern Finland. They left Russia in 1786 and eventually took up residence at the Ludwigsburg Palace, where Fritz and his brother received a strict education. In 1797, his father became the reigning Duke of Württemberg, and Fritz was the Hereditary Prince. By this time, Fritz’s relationship with his father had grown strained, as Fritz rebelled against his strict upbringing and his father’s domineering manner. He attended the University of Tübingen and served as a volunteer in the Austrian Army. Despite returning to Württemberg in 1801, his relationship with his father continued to deteriorate, compounded by Fritz’s relationship with Therese von Abel, the daughter of a politician. Fritz once again left Württemberg in 1803, settling in Saarburg, where Therese gave birth to twins who died shortly after birth.

Fritz returned to Württemberg in 1805, and although his father did not include him in the affairs of state, he set up his own court. The following year, Württemberg became a Kingdom but was soon defeated after joining the coalition against Napoléon. The French Emperor, wanting to establish close dynastic ties to Württemberg, arranged for the marriage of his brother Jérôme, to Fritz’s sister Catherina.

Princess Karoline Auguste of Bavaria. source: Wikipedia

To avoid being forced into a marriage by Napoleon, Fritz quickly negotiated to marry Princess Karoline Auguste of Bavaria, the daughter of King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria and Augusta Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstadt. The couple was married in Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, now in the German state of Bavaria, on June 8, 1808. Fritz had no interest in his wife, they had no children, and his marriage would be relatively short-lived. Soon after his marriage, Fritz met his brother-in-law Jérôme’s former mistress Blanche La Flèche, and began an affair that would continue for much of his life. However, Fritz also fell in love with someone else.

Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna. source: Wikipedia

While in London in 1814, Fritz met and fell in love with his first cousin, Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna of Russia. Ekaterina was the daughter of Paul I, Emperor of All Russia and his second wife Princess Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg, and was the widow of Duke Georg of Oldenburg. With Napoleon no longer in power, Fritz quickly sought a divorce from Karoline Auguste. After she quickly agreed, and with the consent of both of their fathers, a divorce was granted in August 1814. However, the Pope did not issue an annulment until January 1816. Later that year, Fritz’s first wife Karoline Auguste married Emperor Franz I of Austria, as his fourth wife.

Twelve days after the annulment was granted, Fritz married Ekaterina in St. Petersburg on January 24, 1816. During their short marriage, the couple had two daughters:

Fritz became King of Württemberg upon his father’s death on October 30, 1816. As a way of distancing himself from his father’s reign, he dropped his first name and chose to reign as King Wilhelm I. He came to the throne during a difficult time in Württemberg, with 1816 being known as the Year Without A Summer. However, Wilhelm and his wife are credited with making great strides to alleviate the suffering and establishing policies and reforms that helped the people of Württemberg, regardless of social class. The king arranged for food and livestock to be imported and established an Agricultural Academy to help promote the growth of crops and better general nutrition amongst his people. The Queen established numerous charities to help the poor and was behind the establishment of the Württemberg State Savings Bank in 1818.

Duchess Pauline of Württemberg. source: Wikipedia

Sadly, the Queen died on January 9, 1819, leaving Wilhelm a widower with two young daughters. To find a stepmother for his children, and hopefully, to provide a male heir, Wilhelm again set out to find a bride. On April 15, 1820, in Stuttgart, Wilhelm married another first cousin, Duchess Pauline of Württemberg. She was the daughter of Duke Ludwig of Württemberg and Princess Henriette of Nassau-Weilburg.

The couple had three children:

King Wilhelm with Queen Pauline and his children – Karl, Sophie, and Marie (center); Katherina and Augusta (bottom). source: Wikipedia

Despite the public perception that the marriage was happy, it was far from it. The King had maintained his affair with Blanche La Flèche, and in 1828, began a relationship with a German actress, Amalie von Stubenrauch, which would last until his death.

Wilhelm’s reign saw the economic boom of the 1830s, the expansion of roads and shipping routes, and a healthy and prosperous economy. But by the mid-1840s, several years of poor harvests had led to a rise in famine and calls for a more democratic government. Protests in 1848, and another revolution in France led to Wilhelm conceding many of the demands being made – reinstating freedom of the press, and agreeing to form a liberal government.

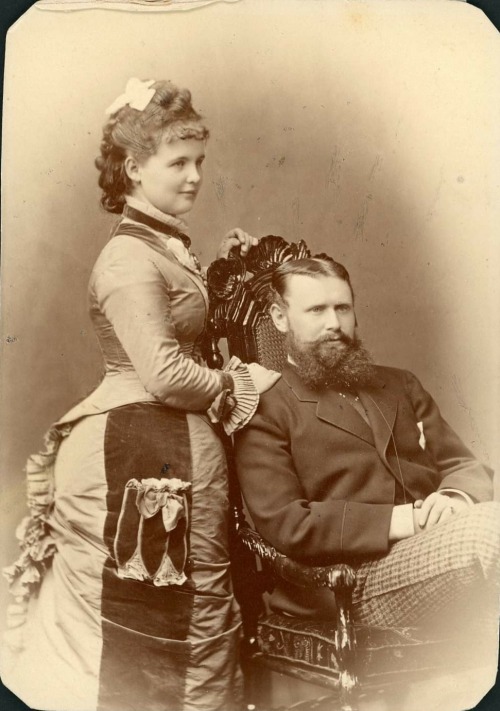

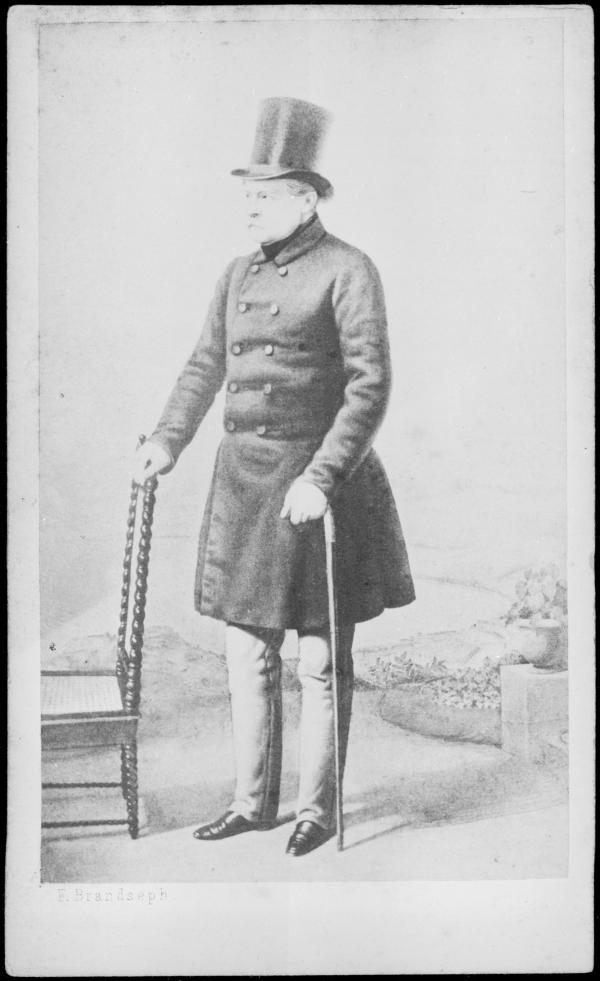

King Wilhelm I, c1860. source: Wikipedia

In his later years, King Wilhelm’s health deteriorated, and he had little contact with his family, instead, he spent all of his time in the company of his mistress Amalie von Stubenrauch. Knowing his death was approaching, he had all of his letters and journals destroyed. King Wilhelm I died on June 25, 1864, at Schloss Rosenstein in Stuttgart, Kingdom of Württemberg, now in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. He was buried in the Württemberg Mausoleum in Stuttgart, next to his second wife. In his will, he left bequests to two of his mistresses and excluded his last wife, Queen Pauline.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Württemberg Resources at Unofficial Royalty