by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2014

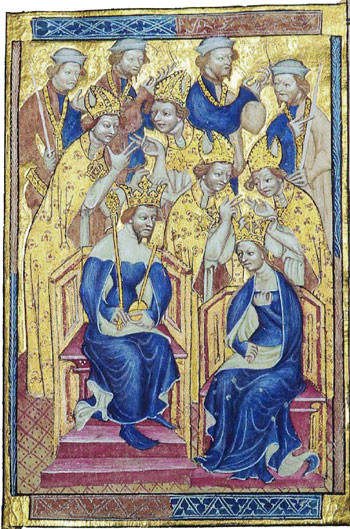

Anne of Bohemia with her husband King Richard II of England; Credit: Wikipedia

Born on May 11, 1366, in Prague, Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic), Anne of Bohemia was the eldest child of Karl IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, and his fourth wife, Elizabeth of Pomerania.

Anne had five siblings:

- Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Hungary and Bohemia and Margrave of Brandenburg (1368–1437), married (1) Mary of Hungary, no surviving issue (2) Barbara of Celje, had issue

- John of Görlitz, Margrave of Moravia and Duke of Görlitz (1370–96), married Richardis Catherine of Sweden, had issue

- Charles (1372 – 1373)

- Margaret of Bohemia (1373–1410), married John III, Burgrave of Nuremberg, had issue

- Henry (1377–78)

Anne had three half-siblings from her father’s first marriage to Blanche of Valois:

- Son (b.1334), died young

- Margaret of Bohemia (1335 – 1349), married King Louis I of Hungary, no issue

- Catherine of Bohemia (1342–95), married (1) Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, no issue (2) Otto V, Duke of Bavaria, Elector of Brandenburg, no issue

Anne had one half-sibling from her father’s second marriage to Anna of Bavaria:

- Wenceslaus (1350–51)

Anne had three half-siblings from her father’s third marriage to Anna von Schweidnitz:

- Elisabeth of Bohemia (1358 – 1373), married Albert III, Duke of Austria, no issue

- Wenceslaus, King of Germany (formally King of the Romans), King of Bohemia (as Wenceslaus IV) and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1361–1419), married (1) Joanna of Bavaria, no issue (2) Sophia of Bavaria, no issue

- Son (born and died 1362)

In 1377, King Edward III of England died after a 50-year reign and because his eldest son Edward, Prince of Wales (the Black Prince) had died the previous year, he was succeeded by his grandson King Richard II who was ten years old. When Richard was 15, a bride was sought for him, and Anne of Bohemia seemed a logical choice as Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire were seen as potential allies against France in the ongoing Hundred Years’ War. However, the potential marriage was unpopular with the nobility and members of Parliament because Anne brought no dowry.

Richard’s tutor and his father’s close friend Sir Simon de Burley went to negotiate the marriage contract and then escort the 15-year-old bride-to-be to England. After Anne arrived in Dover, England, a huge wave wrecked her ship and this was seen as a bad omen. The young couple was married at Westminster Abbey on January 20, 1382, the fifth royal wedding at the Abbey. It was not until the wedding of Princess Patricia of Connaught, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and Alexander Ramsay in 1919, 537 years later, that another royal wedding was held at Westminster Abbey.

Anne is credited with introducing two fashion items in England. Women had ridden horses astride, or pillion, seated sideways on a cushion behind the male rider’s saddle. It is said that Anne introduced the earliest sidesaddle in England, which was chair-like with the woman sitting sideways on the horse with her feet on a small footrest. Anne also introduced the horned headdress, two feet tall and wide, shaped like a crescent moon, and draped with gauze or net.

14th-century fashion; Photo: Wikipedia

Although Anne was initially unpopular, she became known as “Good Queen Anne” because of her kind-hearted ways. She was known to intercede on behalf of numerous people to obtain pardons. Shortly after her marriage, she obtained pardons for participants in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. In 1388, she unsuccessfully pleaded for the life of Sir Simon de Burley, who had escorted her to England. In 1392, she mediated a reconciliation between the city of London and her husband, resulting in a spectacular royal progress through the city with the King and Queen on horseback wearing their crowns. However, Anne of Bohemia failed to fulfill a queen’s most important duty. During the twelve years of her marriage, she failed to produce an heir to the throne.

In June of 1394, Anne became ill with the plague while at Sheen Palace with her husband. She died three days later on June 7, 1394, at the age of 28. King Richard II was so devastated by Anne’s death that he ordered Sheen Palace to be destroyed. For almost 20 years it lay in ruins until King Henry V started a rebuilding project in 1414. King Richard gave Anne a magnificent funeral. The funeral procession made its way from Sheen Palace to Westminster Abbey lit by candles and torches made from wax specially imported from Flanders. Those in the procession were dressed all in black and wore black hoods. King Richard was angered when Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel arrived late for the funeral. The king struck the earl in the face with his scepter.

Funeral Procession of Anne of Bohemia; Credit: Wikipedia

Richard had a tomb built for his wife at Westminster Abbey. Unusually, he had his effigy made to lie alongside Anne’s on the tomb with their hands clasped, although their hands eventually broke off. King Richard II married a second time to six-year-old Isabella of Valois in 1396 and that marriage was also childless. In 1399, King Richard II was deposed and imprisoned by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke (who became King Henry IV), son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. He died in Pontefract Castle on or about February 14, 1400, probably from starvation, although it is possible he was murdered. Richard was originally buried at Kings Langley Priory in Hertfordshire, England. When King Henry V came to the throne in 1413, he ordered that the remains of King Richard II be transferred to Westminster Abbey to join Anne in the tomb Richard had built for them in the St. Edward the Confessor Chapel, next to the tomb of Richard’s grandfather King Edward III.

Tomb of King Richard II of England and Anne of Bohemia in Westminster Abbey; Photo Credit – http://www.westminster-abbey.org

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Plantagenet Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Index

- House of Plantagenet Index (1216 – 1399)

- British Royal Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Other Important Events

- Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present)

- History and Traditions: Norman and Plantagenet Weddings

- House of Plantagenet Burial Sites