by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2024

The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, were originally divided into several independent chiefdoms. The Kingdom of Hawaii was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great of the independent island of Hawaii, conquered the independent islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Lanai, and unified them under one government and ruled as Kamehameha I, King of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauai and Niihau voluntarily joined the Kingdom of Hawaii. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

In 1778, British explorer James Cook visited the islands. This led to increased trade and the introduction of new technologies and ideas. In the mid-19th century, American influence in Hawaii dramatically increased when American merchants, missionaries, and settlers arrived on the islands. Protestant missionaries converted most of the native people to Christianity. Merchants set up sugar plantations and the United States Navy established a base at Pearl Harbor. The newcomers brought diseases that were new to the indigenous people including influenza, measles, smallpox, syphilis, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. At the time of James Cook’s arrival in 1778, the indigenous Hawaiian population is estimated to have been between 250,000 and 800,000. By 1890, the indigenous Hawaiian population declined to less than 40,000.

In 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, her cabinet, and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This led to the 1898 annexation of Hawaii as a United States territory. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States.

In 1993, one hundred years after the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown, the United States Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution which “acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum”. As a result, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom in Hawaii, was established along with ongoing efforts to redress the indigenous Hawaiian population.

********************

Liliuokalani, Queen of the Hawaiian Islands, 1891; Credit – Wikipedia

Liliuokalani, Queen of the Hawaiian Islands was the only queen regnant and the last monarch of the Hawaiian Islands, reigning from 1891 until she was deposed in 1893. She was the composer of Aloha ʻOe or Farewell to Thee, one of the most recognizable Hawaiian songs. Born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha on September 2, 1838, in Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu in the Kingdom of Hawaii, now in the state of Hawaii, she was the third but second surviving of the seven children and the eldest of the three daughters of first cousins Caesar Kaluaiku Kamakaʻehukai Kahana Keola Kapaʻakea and Analea Keohokālole. Liliuokalani was baptized by American missionary Reverend Levi Chamberlain on December 23, 1893, and given the Christian name Lydia.

Liliuokalani‘s family was aliʻi nui, Hawaiian nobility, and were distantly related to the reigning House of Kamehameha, sharing common descent from Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, King of the island of Hawaii and the great-grandfather of Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Her father Caesar Kapaʻakea was a Hawaiian chief who served in the House of Nobles from 1845 until he died in 1866 and on the King’s Privy Council from 1846 – 1866. Her mother Analea Keohokālole, who was of a higher rank than her husband, was a Hawaiian chiefess and a member of the House of Nobles from 1841 to 1847, and on the King’s Privy Council 1846 to 1847.

Liliuokalani had six siblings who survived infancy:

- James Kaliokalani (1835 – 1852), died in his teens

- Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands (1836 – 1891), born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua, married Kapiʻolani Napelakapuokakaʻe, no children

- Anna Kaʻiulani (1842 – ?)

- Kaʻiminaʻauao (1845 – 1848), died from measles during an epidemic of measles, whooping cough, and influenza that killed more than 10,000 Native Hawaiians

- Miriam Likelike (1851 – 1887), married Archibald Scott Cleghorn, Scottish businessman, had one daughter Princess Kaʻiulani, the last heir to the throne before the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

- William Pitt Leleiohoku II (1855 – 1877), unmarried, died from rheumatic fever

Liliuokalani in 1853; Credit – Wikipedia

Liliuokalani was declared eligible to be in the line of succession by the royal decree of King Kamehameha III and therefore attended the Chiefs’ Children’s School, later known as Royal School, in Honolulu, which is still in existence as a public elementary school, the Royal Elementary School, the oldest school on the island of Oahu. Her classmates included the other children declared eligible to be in the line of succession including her siblings James Kaliokalani and the future King Kalākaua, and their thirteen royal relations including the future kings Kamehameha IV, Kamehameha V, and Lunalilo.

After her schooling was complete, Liliuokalani became a part of the young social elite during the reign of King Kamehameha IV (reigned 1855 – 1863). In 1856, when King Kamehameha IV announced that he would marry their classmate Emma Rooke, there were some at the Hawaiian court who thought that his bride should be Liliuokalani because she was his equal in birth and rank. However, Liliuokalani became a close friend of Queen Emma and was a maid of honor at Emma’s wedding and one of her ladies-in-waiting.

After a brief engagement to William Charles Lunalilo, the future Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (reigned 1873 – 1874), Liliuokalani became romantically involved with the American-born John Owen Dominis, a staff member to Prince Lot Kapuāiwa, the future King Kamehameha V, and then a secretary to King Kamehameha IV. Born on March 10, 1832, in Schenectady, New York, John was the son of sea captain John Dominis, originally from Trieste, then part of the Austrian Empire, now in Italy, who emigrated to the United States, and American-born Mary Lambert Jones Dominis. In 1837, the couple relocated to the Kingdom of Hawaii with their son John. Liliuokalani and John had known each other from childhood. John attended a school next to the Royal School, would climb the fence to observe the princes and princesses, and became friends with them.

John Owen Dominis, Prince Consort of the Hawaiian Islands; Credit – Wikipedia

On September 16, 1862, Liliuokalani and John were married in an Anglican ceremony by Reverend Samuel Chenery Damon, a missionary to Hawaii and pastor of the Seamen’s Bethel Church in Honolulu. The couple moved into the Dominis residence, Washington Place in Honolulu. However, the marriage was not happy and was childless. John chose to socialize without Liliuokalani and his mother Mary Dominis looked down upon her non-caucasian daughter-in-law. Liliuokalani noted in her memoir that her mother-in-law considered her an “intruder” but became more affectionate in her later years.

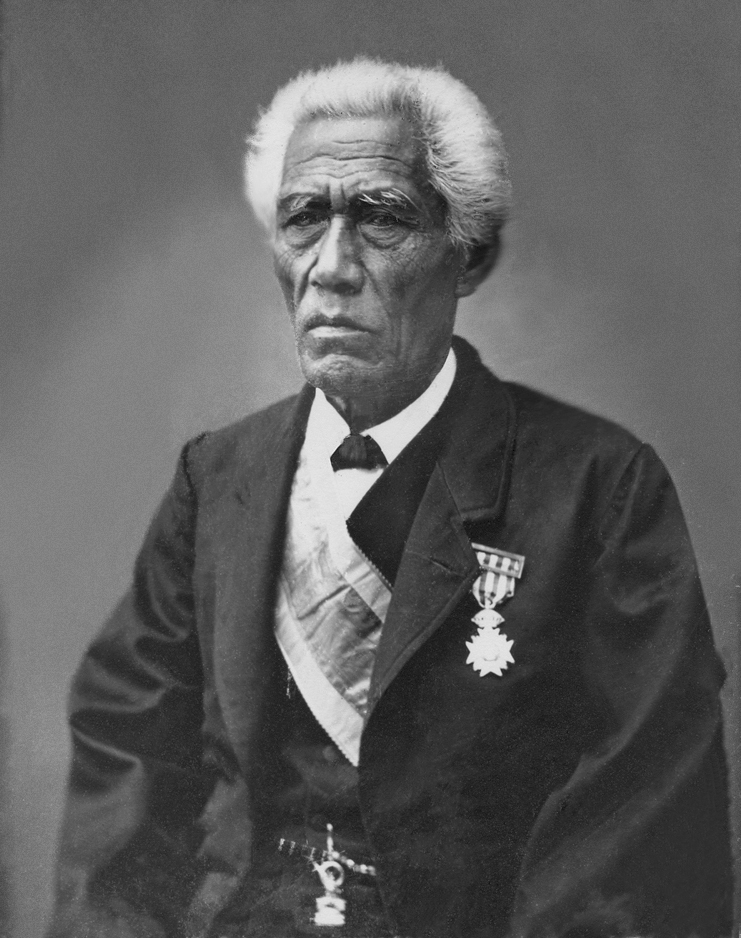

Liliuokalani’s brother David (King Kalākaua); Credit – Wikipedia

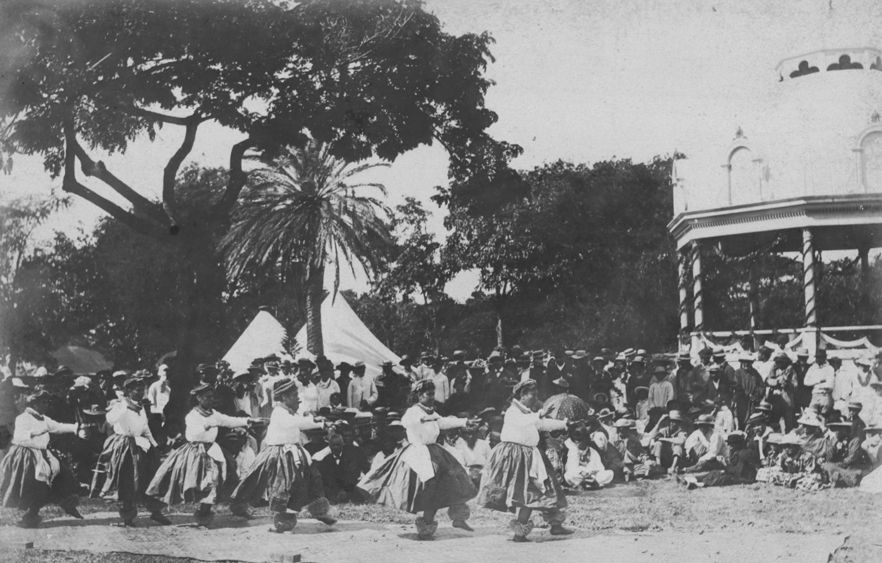

On February 3, 1874, Lunalilo, King of the Hawaiian Islands (born William Charles Lunalilo) died from tuberculosis at the age of 39 without naming an heir. As King Lunalilo had wanted to make Hawaii more democratic, it is thought that he wished to have the people choose their next ruler. The Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the people’s representatives, would choose the next monarch from the eligible royal family members. Queen Emma, the widow of King Kamehameha IV, claimed that King Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but he died before a formal proclamation could be made. She decided to run in the election against Liliuokalni’s brother David who had lost to King Lunalilo in a similar election in 1873. While the Hawaiian people supported Emma, it was the legislature that elected the new monarch. They favored David who won the election 39 – 6. David reigned as King Kalākaua and became the first of two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaiian Islands from the House of Kalākaua, who were also the last two monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Upon his accession to the throne, King Kalākaua (David) named his brother William Pitt Leleiohoku II as his heir apparent. When his brother died from rheumatic fever in 1877, King Kalākaua named his sister Liliuokalani as his heir apparent. She acted as regent during her brother’s absences from the country.

Liliuokalani (left) and Kapiʻolani (right) at the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria; Credit – Wikipedia

In April 1887, Liliuokalani, her husband John Owen Dominis, and her sister-in-law Queen Kapiʻolani were part of the delegation from the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands sent to attend the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in London. Kapiʻolani and Liliuokalani were granted an audience with Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. They attended the special Jubilee service at Westminster Abbey and were seated with other foreign royal guests.

On November 25, 1890, Liliuokalani’s brother King Kalākaua sailed for California aboard the USS Charleston. The purpose of the trip was uncertain but there were reports that the trip was for his ill health. David arrived in San Francisco, California on December 5, 1890. He suffered a minor stroke in Santa Barbara, California, and was rushed back to San Francisco. Two days before his death, he lapsed into a coma. King Kalākaua died in San Francisco, California on January 20, 1891, aged 54. On January 29, 1891, in the presence of the cabinet ministers and the Supreme Court justices, the new Queen Liliuokalani took the oath of office to uphold the constitution and became the first and the only female monarch of the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands. Liliuokalani’s husband John Owen Dominis died less than a year later on August 27, 1891, at their Washington Place home and was buried in the Mauna Ala Royal Mausoleum in Honolulu.

In 1875, during the reign of Queen Liliuokalani’s brother, the Reciprocity Treaty, a free trade agreement between the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands and the United States, gave free access to the United States market for sugar and other products grown in the Kingdom of Hawaii. In return, Hawaii guaranteed the United States that it would not cede or lease any of its land to other foreign powers. Then in 1887, also during the reign of Queen Liliuokalani’s brother, a new constitution was proposed by anti-monarchists that would strip the absolute Hawaiian monarchy of much of its authority and transfer power to a coalition of American, European, and native Hawaiians. It became known as the Bayonet Constitution because of the armed militia that forced King Kalākaua to sign it or be deposed.

During her reign, Queen Liliuokalani attempted to draft a new constitution that would restore the power of the monarchy. Threatened by Queen Liliuokalani’s attempts to negate the Bayonet Constitution, in 1893, a group of local businessmen and politicians composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national overthrew Queen Liliuokalani and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The overthrow was supported by the landing of United States Marines to protect American interests, making the monarchy unable to protect itself. The Republic of Hawaii was established but the ultimate goal was the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the United States which would happen in 1898.

Liliʻuokalani being escorted up the steps of ʻIolani Palace, where she was imprisoned after the unsuccessful uprising of 1895; Credit – Wikipedia

In January 1895, a short, unsuccessful uprising to restore the monarchy was launched. On January 16, 1895, Liliuokalani was arrested and placed under house arrest at the ʻIolani Palace in Honolulu when firearms were found at her home, Washington Place, after a tip from a prisoner. On January 24, 1895, Liliuokalani was forced to abdicate, officially ending the monarchy. Liliuokalani was tried by the military commission of the new Republic of Hawaii and was sentenced to five years of hard labor in prison and fined $5,000. The sentence was commuted on September 4, 1895, to imprisonment in the ʻIolani Palace. On October 13, 1896, the Republic of Hawaii granted Liliuokalani a full pardon and restored her civil rights.

Cover of Liliuokalani’s song Aloha ʻOe, 1890; Credit – Wikipedia

After her pardon, Liliuokalani felt the need to leave Hawaii, at least for a while. From December 1896 through January 1897, Liliuokalani stayed in Brookline, Massachusetts with her late husband’s cousins William Lee and Sara White Lee of the Lee & Shepard Publishing House. William and Sara and Liliuokalani’s long-time friend Julius A. Palmer Jr. helped her compile and publish her book of Hawaiian songs and her memoir Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen which gave her point of view of the history of her country and her overthrow. Liliuokalani’s most famous song is Aloha ʻOe or Farewell to Thee. It was originally written as a lover’s goodbye, but the song came to be regarded as a symbol of the loss of her country, the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands. It remains one of the most recognizable Hawaiian songs.

Washinton Place, Liliuokalani’s home in Honolulu; Credit – By Frank Schulenburg – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=146081316

At the end of her visit to Massachusetts, Liliuokalani began to divide her time between Hawaii and Washington, D.C., where she worked to plead her case to the United States. Unsuccessful attempts were made to restore the monarchy and oppose annexation and the United States formally annexed Hawaii as a territory in 1898. In 1909, Liliuokalani brought an unsuccessful lawsuit against the United States under the Fifth Amendment seeking the return of the Hawaiian Crown Lands. The American courts invoked an 1864 Kingdom of Hawaii Supreme Court decision over a case involving Dowager Queen Emma and King Kamehameha V. In this decision, the courts found that the Crown Lands were not necessarily the private possession of the monarch in the strictest sense of the term. In 1911, Liliuokalani was granted a lifetime pension of $1,250 a month by the Territory of Hawaii.

Queen Liliuokalani lying in state at Iolani Palace; Credit – Wikipedia

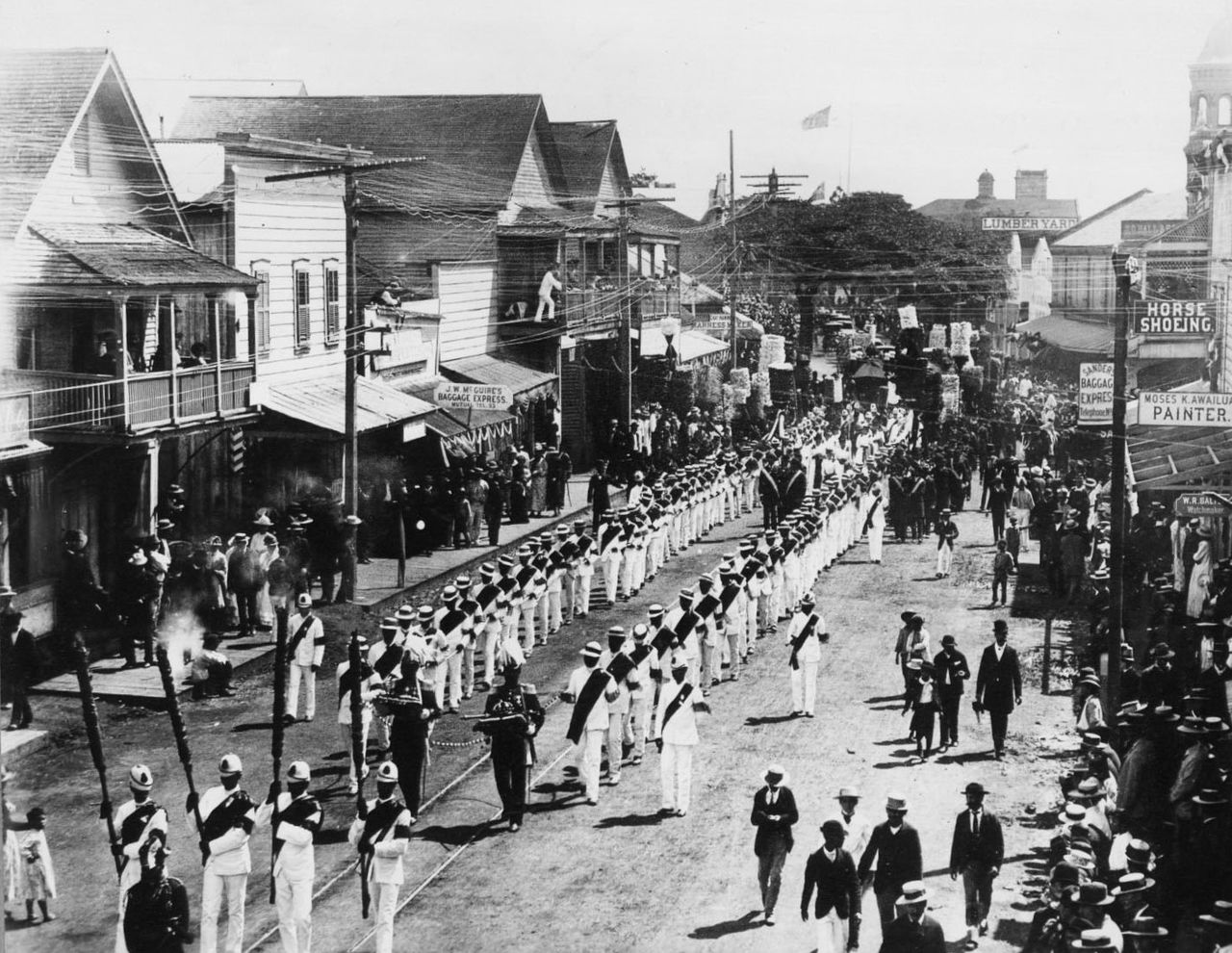

By 1917, her health was suffering. She lost the use of her legs and her mental capacity was severely diminished. On the morning of November 11, 1917, Liliʻuokalani died at the age of seventy-nine at her home, Washington Place in Honolulu, Hawaii. The former queen lay in state at Kawaiahaʻo Church for public viewing, after which she received a state funeral in the throne room of ‘Iolani Palace, on November 18, 1917. Composer Charles E. King led a youth choir in Aloha ʻOe as her coffin was moved to her burial place. The procession participants and the crowds of people along the route began to sing the song. Liliuokalani was interred with her family members in the Kalākaua Crypt on the grounds of the Royal Mausoleum of Mauna ʻAla in Honolulu, Hawaii.

The burial vault of Queen Liliuokalani in the Kalākaua Crypt; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Flantzer, Susan. (2024). Kalākaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands. Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/kalakaua-king-of-the-hawaiian-islands/

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2024). Liliʻuokalani. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lili%CA%BBuokalani

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Royal Mausoleum (Mauna ʻAla). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Mausoleum_(Mauna_%CA%BBAla)

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2023). Hawaiian Kingdom. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaiian_Kingdom