by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

The five eldest surviving daughters of King Edward IV, left to right: Elizabeth, Cecily, Anne, Catherine, and Mary. This stained glass window in Canterbury Cathedral was made by order of King Edward IV; Credit – Wikipedia

Born on November 2, 1475, at the Palace of Westminster in London, England, Anne of York, Lady Howard was the fifth of the seven daughters and the seventh of the ten children of King Edward IV of England, the first King of England from the House of York, and Elizabeth Woodville. Anne’s paternal grandparents were Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York and Cecily Neville, both great-grandchildren of King Edward III of England. Her maternal grandparents were Sir Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers and Jacquetta of Luxembourg.

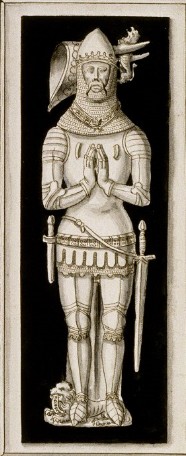

Anne’s father King Edward IV of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Anne’s father King Edward IV was the eldest surviving son of Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York who had a strong claim to the English throne. The social and financial troubles that followed the Hundred Years’ War, combined with the mental disability and weak rule of the Lancastrian King Henry VI had revived interest in the claim of Richard, 3rd Duke of York, and so the Wars of the Roses were fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet, the House of Lancaster and the House of York between 1455 and 1487. Richard, 3rd Duke of York was killed on December 30, 1460, at the Battle of Wakefield and his son Edward was then the leader of the House of York. After winning a decisive victory on March 2, 1461, at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross, 19-year-old Edward proclaimed himself king. In 1464, King Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville.

Anne’s mother Elizabeth Woodville; Credit – Wikipedia

Anne had nine siblings:

- Elizabeth of York (1466 – 1503), married King Henry VII of England, had seven children including King Henry VIII of England, Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots, and Mary Tudor, Queen of France

- Mary of York (1467 – 1482), unmarried, died in her teens

- Cecily of York, Viscountess Welles (1469 – 1507), married (1) Ralph Scrope of Upsall, no children, marriage annulled (2) John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles, had two daughters who died young (3) Sir Thomas Kyme, possible children

- King Edward V of England (1470 – circa 1483), briefly succeeded his father, as King Edward V of England, was the elder of the Princes in the Tower

- Margaret of York (born and died 1472)

- Richard of Shrewsbury, 1st Duke of York (1473 – circa 1483), was the younger of the Princes in the Tower

- George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Bedford (1477 – 1479), died in childhood probably from the bubonic plague

- Catherine of York (1479 – 1527), married William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, had two sons and one daughter

- Bridget of York (1480 – 1517), became a nun

Anne had two half-brothers from her mother’s first marriage to Sir John Grey of Groby:

- Thomas Grey, 1st Marquess of Dorset (1455 – 1501), married (1) Anne Holland, no children; (2) Cecily Bonville, 7th Baroness Harington and 2nd Baroness Bonville, had 14 children; Thomas and Cecily are the great-grandparents of Lady Jane Grey

- Sir Richard Grey (1457 – 1483), unmarried, executed by Richard, Duke of Gloucester (future King Richard III)

In 1479, King Edward IV began negotiations with Maximilian, Archduke of Austria, later Holy Roman Emperor, for his daughter Anne to marry Maximilian’s son Philip of Habsburg. Maximilian was married to Mary, Duchess of Burgundy, a very wealthy heiress with vast lands that Philip would inherit. There was also a York family connection: King Edward IV’s sister and Anne’s aunt, Margaret of York, was the stepmother of Mary, Duchess of Burgundy. On August 5, 1480, the marriage negotiations were completed. However, after the unexpected death of King Edward IV, the marriage contract between Anne and Philip of Habsburg was rejected by Philip’s father.

Anne’s brother King Edward V of England, one of the missing Princes in the Tower; Credit – Wikipedia

When Anne was seven-years-old, her father King Edward IV died on April 9, 1483, a few weeks before his 41st birthday. Anne’s twelve-year-old brother succeeded their father as King Edward V, and King Edward IV’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was named Lord Protector of his young nephew and moved to keep the Woodvilles, the family of Edward IV’s widow Elizabeth Woodville, from exercising power. The widowed queen sought to gain political power for her family by appointing family members to key positions and rushing the coronation of her young son. The new king was accompanied to London by his maternal uncle Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers and his half-brother Sir Richard Grey. Rivers and Grey were accused of planning to assassinate Richard, Duke of Gloucester, and were arrested, and taken to Pontefract Castle, where they were later executed without trial. Richard, Duke of Gloucester then proceeded with the new king to London where Edward V was presented to the Lord Mayor of London. For their safety, King Edward V and his nine-year-old brother Richard, Duke of York were sent to the Tower of London and were never seen again. They are the famous Princes in the Tower.

On June 22, 1483, a sermon was preached at St. Paul’s Cross in London declaring Edward IV’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville invalid and his children illegitimate. This information apparently came from Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, who claimed a legal pre-contract of marriage to Eleanor Butler, had invalidated King Edward IV’s later marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. The citizens of London presented Richard, Duke of Gloucester with a petition urging him to assume the throne, and he was proclaimed king on June 26, 1483. King Richard III and his wife Anne Neville were crowned in Westminster Abbey on July 6, 1483, and their son Edward of Middleham was created Prince of Wales. In January 1484, Parliament issued the Titulus Regius, a statute proclaiming Richard the rightful king.

Anne’s brother-in-law King Henry VII of England; Credit – Wikipedia

On August 22, 1485, Henry Tudor from the House of Lancaster defeated King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field and became King Henry VII, the first Tudor king of England. On January 18, 1486, Henry VII married Anne’s eldest sister Elizabeth of York uniting the House of Lancaster and the House of York into the new House of Tudor. Henry VII had Parliament repeal the Titulus Regius, the act that declared King Edward IV’s marriage invalid and his children illegitimate, thereby legitimizing his wife.

Anne’s sister Elizabeth of York, wife of King Henry VII and mother of King Henry VIII; Credit – Wikipedia

Anne was ten years old when her eldest sister Elizabeth married King Henry VII and along with her other sisters, she came under the supervision of her eldest sister, now Queen Consort of England. Anne participated in court ceremonies including Easter, Pentecost, Christmas celebrations, and other court events. In 1486, she participated in the christening of her nephew Arthur, Prince of Wales by carrying the baptismal veil which covered the head of the prince after the christening. Anne performed the same role at the christening of her niece Margaret Tudor in 1489.

Anne’s mother Queen Dowager Elizabeth Woodville died at Bermondsey Abbey in London, England on June 8, 1492, at the age of 55. Except for her daughter Queen Elizabeth, who was awaiting the birth of her fourth child, and her daughter Cecily, her other daughters Anne, Catherine, and Bridget attended her funeral at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle where Elizabeth Woodville was buried with her husband King Edward IV of England.

A later portrait of Anne’s husband, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk by Hans Holbein, circa 1539, depicting Howard as Earl Marshal of England, wearing the Order of the Garter with the St George pendant

When Anne reached a marriageable age, her sister Queen Elizabeth searched for a husband for Anne among the British nobility. King Richard III had planned to marry his niece Anne to Lord Thomas Howard, the eldest son and heir of Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Surrey (later 2nd Duke of Norfolk), and so Queen Elizabeth decided upon Thomas Howard. Anne was well acquainted with her future husband since childhood because his father served her father in his private chambers. 19-year-old Anne and 21-year-old Lord Thomas Howard were married at Greenwich Palace on February 4, 1495.

Anne and Thomas had four children but none survived childhood:

- Thomas Howard (circa 1496 – 1508 or 1509)

- Son (died before baptism)

- Daughter (died before baptism)

- Daughter (died before baptism)

On February 2, 1503, Anne’s eldest sister Queen Elizabeth gave birth to her seventh child, a daughter Katherine. Shortly after giving birth, Elizabeth became ill with puerperal fever (childbed fever) and died on February 11, 1503, her 37th birthday. Little Katherine died on February 18, 1503. Anne’s grief at the loss of her sister was so great that she could not bear to attend the entire funeral at Westminster Abbey. Her brother-in-law King Henry VII was so shaken by his wife’s death that he went into seclusion and would only see his mother.

In 1509, Anne’s brother-in-law King Henry VII died and was succeeded by his son and Anne’s nephew King Henry VIII. Anne died after November 22 or 23, 1511, but before 1513, aged 36 – 38. She was originally buried at Thetford Priory in Thetford, Norfolk, England.

In 1513, Anne’s widower Thomas Howard married Lady Elizabeth Stafford, daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Lady Eleanor Percy, daughter of Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland. Thomas and Eleanor had five children. In 1514, Thomas was created Earl of Surrey and when his father died in 1524, Thomas became the 3rd Duke of Norfolk.

During the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536 – 1541), when the Catholic abbeys, monasteries, priories, and convents were disbanded (many were destroyed) and their property and assets were confiscated, Anne’s widower Thomas Howard petitioned King Henry VIII to convert Thetford Priory into a parish church because Howard family members including Anne and King Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset who had married Lady Mary Howard, a daughter of Thomas Howard by his second wife, were interred there. Other nobles made similar petitions but King Henry VIII refused them all. However, he did allow the Dissolution of the Monasteries to be suspended for a while so that those nobles who wished to rebury the remains of their relatives could do so. Thomas Howard moved the remains of the Howard family members from Thetford Priory to the Church of St. Michael the Archangel in Framlingham, Suffolk, England. He ordered an ornate tomb for Anne at the Church of St. Michael the Archangel with the figures of the twelve apostles around the four sides.

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk holds the distinction of being the uncle of Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, King Henry VIII’s two beheaded wives. Anne Boleyn was the daughter of Thomas’s sister Lady Elizabeth Howard who married Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire. Catherine Howard was the daughter of Thomas’s brother Lord Edmund Howard and his first wife Joyce Culpeper. As Lord High Steward, Thomas Howard, 3d Duke of Norfolk presided at the trial that condemned to death his niece Anne Boleyn.

Tomb of Anne of York and Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk; Credit – www.findagrave.com

When Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk died on August 25, 1554, aged 81, he was buried with his first wife Anne of York at the Church of St. Michael the Archangel in Framlingham, Suffolk, England. However, since Anne was of royal lineage, Thomas was buried to her left instead of on her right as was customary.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Anne of York (daughter of Edward IV) (2023) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_of_York_(daughter_of_Edward_IV) (Accessed: January 30, 2023).

- Flantzer, Susan. (2016) Elizabeth of York, Queen of England, Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/elizabeth-of-york-queen-of-england/ (Accessed: January 30, 2023).

- Flantzer, Susan. (2016) King Edward IV of England, Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-edward-iv-of-england/ (Accessed: January 30, 2023).

- Jones, Dan. (2012) The Plantagenets. New York: Viking.

- St. Michael the Archangel’s Church, Framlingham (2022) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Michael_the_Archangel’s_Church,_Framlingham (Accessed: January 30, 2023).

- Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk (2023) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Howard,_3rd_Duke_of_Norfolk (Accessed: January 30, 2023).

- Weir, Alison. (1989) Britain’s Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. London: Vintage Books.

- Williamson, David. (1996) Brewer’s British Royalty: A Phrase and Fable Dictionary. London: Cassell.