by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Cecily Neville, Detail from the 15th century Neville Book of Hours; Credit – Wikipedia

A great-granddaughter of King Edward III of England, Cecily Neville was the wife of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, also a great-grandchild of King Edward III, who was a claimant to the English throne and the leader of the Yorkist faction during the Wars of the Roses. She was also the mother of King Edward IV of England and King Richard III of England, the grandmother of the ill-fated King Edward V of England, and the great-grandmother of King Henry VIII of England. Cecily outlived all but two of her twelve children. She was alive when her granddaughter Elizabeth of York, daughter of King Edward IV, married Henry Tudor who had defeated her son King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 and then succeeded to the English throne by right of conquest as King Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch. Cecily was alive when her granddaughter Elizabeth of York gave birth to her first three children, Cecily’s great-grandchildren Arthur, Prince of Wales, Margaret Tudor, and King Henry VIII. Through Margaret Tudor, who married James IV, King of Scots, Cecily is an ancestor of the British royal family and many other European royal families.

Born May 3, 1415, at Raby Castle in Durham, England, Cecily was the youngest of the fourteen children and the youngest of the five daughters of Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland and his second wife Joan Beaufort. Cecily’s paternal grandparents were John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby, and Maud Percy, daughter of Henry de Percy, 2nd Baron Percy. Her maternal grandparents were John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, and his third wife and former mistress Katherine Swynford. John of Gaunt was the third surviving son of King Edward III of England, and so Cecily was the great-granddaughter of King Edward III.

Cecily’s mother Joan Beaufort and her daughters from her second marriage, from the Neville Book of Hours, circa 1427-1432; Credit – Wikipedia

Cecily had thirteen elder siblings:

- Katherine Neville (circa 1397 – 1483), married (1) John de Mowbray, 2nd Duke of Norfolk, had one son (2) Sir Thomas Strangways, had two daughters (3) John Beaumont, 1st Viscount Beaumont, no children (4) Sir John Woodville, no children

- Eleanor Neville (circa 1398 – 1472), married (1) Richard le Despencer, 4th Baron Burghersh, no children (2) Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland, had ten children

- Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury (1400 – 1460), married Alice Montacute, 5th Countess of Salisbury, had twelve children including Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (1428–1471), “The Kingmaker”

- Henry Neville (born and died circa 1402)

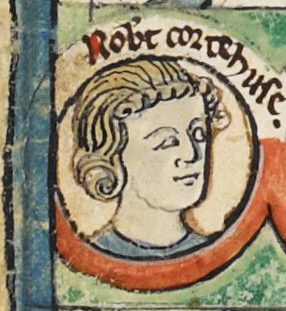

- Robert Neville, Bishop of Salisbury and Bishop of Durham (1404 – 1457)

- William Neville, 1st Earl of Kent (circa 1405 – 1463), married Joan de Fauconberg, 6th Baroness Fauconberg, had five children

- John Neville (born and died circa 1406).

- George Neville, 1st Baron Latimer (circa 1407 – 1469), married Elizabeth Beauchamp, had four children

- Anne Neville (c. 1408–1480), married (1) Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, had twelve children (2) Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy, no children

- Thomas Neville (born and died circa 1410)

- Cuthbert Neville (born and died circa 1411).

- Joan Neville (circa 1412 – 1453), a nun

- Edward Neville, 3rd Baron Bergavenny (circa 1414 – 1476), married (1) Elizabeth Beauchamp (not the same Elizabeth Beauchamp as his brother George’s wife), had four children (2) Katherine Howard, had three daughters

Cecily had eight half-siblings from her father’s first marriage to Margaret Stafford (circa 1364 – 1396):

- Maud Neville (? – 1438), married Piers Mauley, 5th Baron Mauley

- Alice Neville (circa 1384 – circa 1434) married (1) Sir Thomas Grey, beheaded for his part in the Southampton Plot, had eight children (2) Sir Gilbert Lancaster, no children

- Philippa Neville 1386 – circa 1453), married Thomas Dacre, 6th Baron Dacre of Gilsland, had nine children

- Sir John Neville (circa 1387 – circa 1420), married Elizabeth Holland, had four children

- Elizabeth Neville, a nun.

- Anne Neville (? – circa1421), married Sir Gilbert Umfraville, no children

- Sir Ralph Neville (circa 1392 – 1458), married his step-sister Mary Ferrers, had five children

- Margaret Neville (circa 1396 – circa 1463), married (1) Richard Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Bolton, had three children (2) William Cressener, had three children

Cecily had two half-sisters from her mother’s first marriage to Robert Ferrers of Wem (circa 1373 – 1396):

- Elizabeth Ferrers (1393 – 1474), married John Greystoke, 4th Baron Greystoke, had twelve children

- Mary Ferrers (1394 – 1458), married her stepbrother Sir Ralph Neville, had five children

Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, detail from the frontispiece of the illuminated manuscript Talbot Shrewsbury Book; Credit – Wikipedia

Cecily’s future husband Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York (1411 – 1460) had a unique place in the succession to the English throne, and this would affect their marriage and their family. Richard was the only surviving son of Richard of Conisbrough, 3rd Earl of Cambridge and his first wife Anne Mortimer. Both Richard’s parents were descendants of King Edward III of England. The House of York, a cadet branch of the House of Plantagenet, descended from two sons of King Edward III: in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, the fourth surviving son of Edward III, and from a female line of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, Edward III’s second surviving son. These two lines came together when Richard’s mother Anne Mortimer, a great-granddaughter of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence married Richard’s father Richard of Conisbrough, a son of Edmund of Langley, Duke of York. (A House of York family tree can be seen at Wikipedia: House of York.)

In 1415, Richard of Conisbrough was one of the three plotters of the Southhampton Plot executed for plotting to depose King Henry V of England (from the House of Lancaster) and place Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, the brother of Richard of Conisbrough’s deceased wife Anne Mortimer on the English throne. Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March had not been aware of the plot and when he found out about it, he told King Henry V. With the execution of his father, four-year-old Richard was an orphan. The title of Richard’s father was not attainted – after being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason), an act of attainder deprived nobles of their titles and lands. The descendants of the attainted noble could no longer inherit his lands or income. Because his father was not attainted, four-year-old Richard inherited his father’s Earl of Cambridge title. Three months later, little Richard’s paternal uncle (his father’s elder brother) Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York was killed at the Battle of Agincourt, and Richard inherited his paternal uncle’s titles and estates. In 1425, when Richard’s maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March died, Richard inherited the lesser title of Earl of March but the greater estates of the Mortimer family along with their claim to the English throne. Richard of York already held a strong claim to the English throne as a male-line great-grandson of King Edward III.

After the death of his father in 1415, the orphaned Richard became a royal ward and was placed in the household of Sir Robert Waterton, loyal to King Henry V and King Henry VI of the House of Lancaster. In 1423, Richard became the royal ward of Cecily’s father Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland. As was his right Neville betrothed his youngest child, nine-year-old daughter Cecily Neville to thirteen-year-old Richard in 1424. Richard and Cecily were married by October 1429.

Richard and Cecily had twelve children including two Kings of England:

- Anne of York (1439 – 1476), married (1) Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter, had one daughter (2) Sir Thomas St. Leger, Anne died giving birth to a daughter

- Henry of York (born and died 1441), died in infancy

- Edward IV, King of England (1442 – 1483), married Elizabeth Woodville, had ten children including the ill-fated Edward V, King of England and Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII, King of England

- Edmund, Earl of Rutland (1443 – 1460), unmarried, killed at the Battle of Wakefield during the Wars of the Roses

- Elizabeth of York (1444 – circa 1503), wife of John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, had eleven children

- Margaret of York (1446 – 1503), married Charles I (the Bold), Duke of Burgundy, no children

- William of York (born and died 1447), died in infancy

- John of York (born and died 1448), died in infancy

- George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1449 – 1478), married Isabel Neville, had four children, George was executed by his brother King Edward IV

- Thomas of York (born and died circa 1450/1451), died in infancy

- Richard III, King of England (1452 – 1485), married Anne Neville, had one son Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales who predeceased his father, Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field

- Ursula of York (born and died 1455), died in infancy

In 1422, 35-year-old King Henry V succumbed to dysentery, a disease that killed more soldiers than battle, leaving his nine-month-old son to inherit his throne as King Henry VI. Over the next decade, Cecily’s husband Richard was a member of the close circle around the young king, in recognition of his place in the line of succession to the English throne. Richard was third in the line of succession after John, 1st Duke of Bedford and Humphrey, 1st Duke of Gloucester, both brothers of King Henry V and paternal uncles of the young King Henry VI.

Shortly before his son Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales was born in 1453, King Henry VI had some kind of mental breakdown. He was unable to recognize or respond to people for over a year. Edward was the heir to the throne, followed by Richard, 3rd Duke of York. During Henry VI’s incapacity, Richard, 3rd Duke of York governed as Lord Protector, and he often quarreled with the Lancastrians at court. In 1448, Richard assumed the surname Plantagenet and then assumed the leadership of the Yorkist faction in 1450. Eventually, things came to a head between Henry VI’s House of Lancaster and Richard’s House of York, and war broke out.

The First Battle of St. Albans on May 22, 1455, traditionally marks the beginning of the Wars of the Roses in England. It was a decisive Yorkist victory. Afterward, there was a peace of sorts, but hostilities started again four years later. At times, Richard was forced to flee to Ireland and continental Europe, but Cecily remained at the family estate Ludlow Castle, caring for her children. She also championed the cause of the House of York. When the Parliament was to decide the fate of her husband, Cecily she traveled to London, where she asked for a pardon if Richard appeared before Parliament within eight days. When this did not happen, his lands were confiscated by the Crown. However, Cecily managed to get an annual allowance of 1000 marks to support herself and the children

On July 10, 1460, King Henry VI was captured at the Battle of Northampton and forced to recognize Richard, 3rd Duke of York as his heir instead of his own son. However, at the Battle of Wakefield on December 30, 1460, the Lancastrians won a decisive victory. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, his second son 17-year-old Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and Cecily’s brother Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, were all killed.

Cecily’s eldest son King Edward IV of England; Credit – Wikipedia

After the death of her husband, Cecily moved to Baynard’s Castle in London, which became the London headquarters of the House of York during the Wars of the Roses. Cecily’s eldest son Edward was now the leader of the Yorkist faction. On February 3, 1461, Edward defeated the Lancastrian army at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross. Edward then took a bold step and declared himself King Edward IV of England on March 4, 1461. His decisive victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton on March 29, 1461, cemented his status as King of England. He was crowned at Westminster Abbey on June 28, 1461. However, the former king, Henry VI, still lived and fled to Scotland.

Cecily was honored as the mother of the king. She regularly appeared beside her son King Edward IV and had much influence. While Edward was in the north of England fighting the remaining forces of the House of Lancaster, Cecily acted as his representative in London. Edward granted his mother a generous allowance of 5000 marks per year. In 1464, when Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville, he built new queen’s quarters for his wife and allowed his mother remain in the queen’s quarters, where she had been living.

Henry VI returned from Scotland in 1464 and took part in an ineffective uprising. In 1465, Henry was captured and taken to the Tower of London. His wife Margaret of Anjou, exiled in France, wanted to restore the throne to her husband. Coincidentally, King Edward IV had a falling out with his major supporters, his brother George, Duke of Clarence, and his first cousin Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as the Kingmaker. Margaret of Anjou, Clarence, and Warwick formed an alliance at the urging of King Louis XI of France. Edward IV was forced into exile, and Henry VI was restored to the throne on October 30, 1470.

Edward IV and his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III) fled to Burgundy where they knew they would be welcomed by their sister Margaret, the wife of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. The Duke of Burgundy provided funds and troops to Edward to enable him to launch an invasion of England in 1471. Edward returned to England in early 1471 and defeated the Lancastrians at the Battle of Barnet. where his cousin Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick was killed. The final decisive Yorkist victory was at the Battle of Tewkesbury on May 4, 1471, where Henry VI’s son Edward, Prince of Wales was killed.

Cecily’s son Edward became King of England once again. Henry VI was returned to the Tower of London and died on May 21, 1471, probably murdered on orders from King Edward IV. Edward IV’s brother George, Duke of Clarence was eventually found guilty of plotting against him, imprisoned in the Tower of London, and privately executed on February 18, 1478.

Cecily’s youngest son King Richard III; Credit – Wikipedia

Had Cecily’s son King Edward IV lived longer, perhaps he would have become one of England’s most powerful kings. He died on April 9, 1483, a few weeks before his 41st birthday. His cause of death is not known for certain. His 12-year-old son very briefly succeeded King Edward IV as King Edward V until he and his brother Richard, Duke of York were declared illegitimate by an Act of Parliament and their uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester crowned King Richard III. Cecily’s grandsons Edward V and his brother Richard were the Princes in the Tower, whose fate is unknown. Cecily’s son King Richard III lost his life and his crown at the Battle of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. On that day, Henry Tudor, the Lancastrian faction leader, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor, King Henry VII.

Cecily’s granddaughter Elizabeth of York, the wife of King Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch; Credit – Wikipedia

By 1485, Cecily’s husband and ten of her twelve children had died. Only her daughters Elizabeth of York (1444 – 1503), who married John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, and Margaret of York (1446 – 1503), who married Charles I, Duke of Burgundy survived. On January 18, 1486, Cecily’s granddaughter Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of King Edward IV, married King Henry VII and became Queen of England. Cecily’s great-grandson Arthur, Prince of Wales was born that same year, her great-granddaughter Margaret Tudor was born in 1489, and her great-grandson, the future King Henry VIII in 1491, all before she died. During the reign of King Henry VII, Cecily devoted herself primarily to her religious interests. Henry VII granted her the right to export wool free of duty and an income based on the income from the estates granted to her by her son King Edward IV in 1461.

Cecily Neville, Duchess of York died on May 31, 1495, aged 80, at Berkhamsted Castle in Hertfordshire, England. She had survived her husband Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York by thirty-five years, and was buried with him and their son Edmund, Earl of Rutland at the Church of Saint Mary and All Saints in Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire, England.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2022. Cecily Neville – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecily_Neville> [Accessed 20 August 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Cecily Neville, Duchess of York – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecily_Neville,_Duchess_of_York> [Accessed 20 August 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_of_York,_3rd_Duke_of_York> [Accessed 20 August 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2022. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/richard-plantagenet-3rd-duke-of-york/> [Accessed 20 August 2022].

- De.wikipedia.org. 2022. Cecily Neville – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecily_Neville> [Accessed 20 August 2022].

- Jones, Dan, 2012. The Plantagenets. New York: Viking.

- Weir, Alison, 1995. The Wars of the Roses. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Williamson, David, 1996. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell.