by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

James II, King of England/James VII, King of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

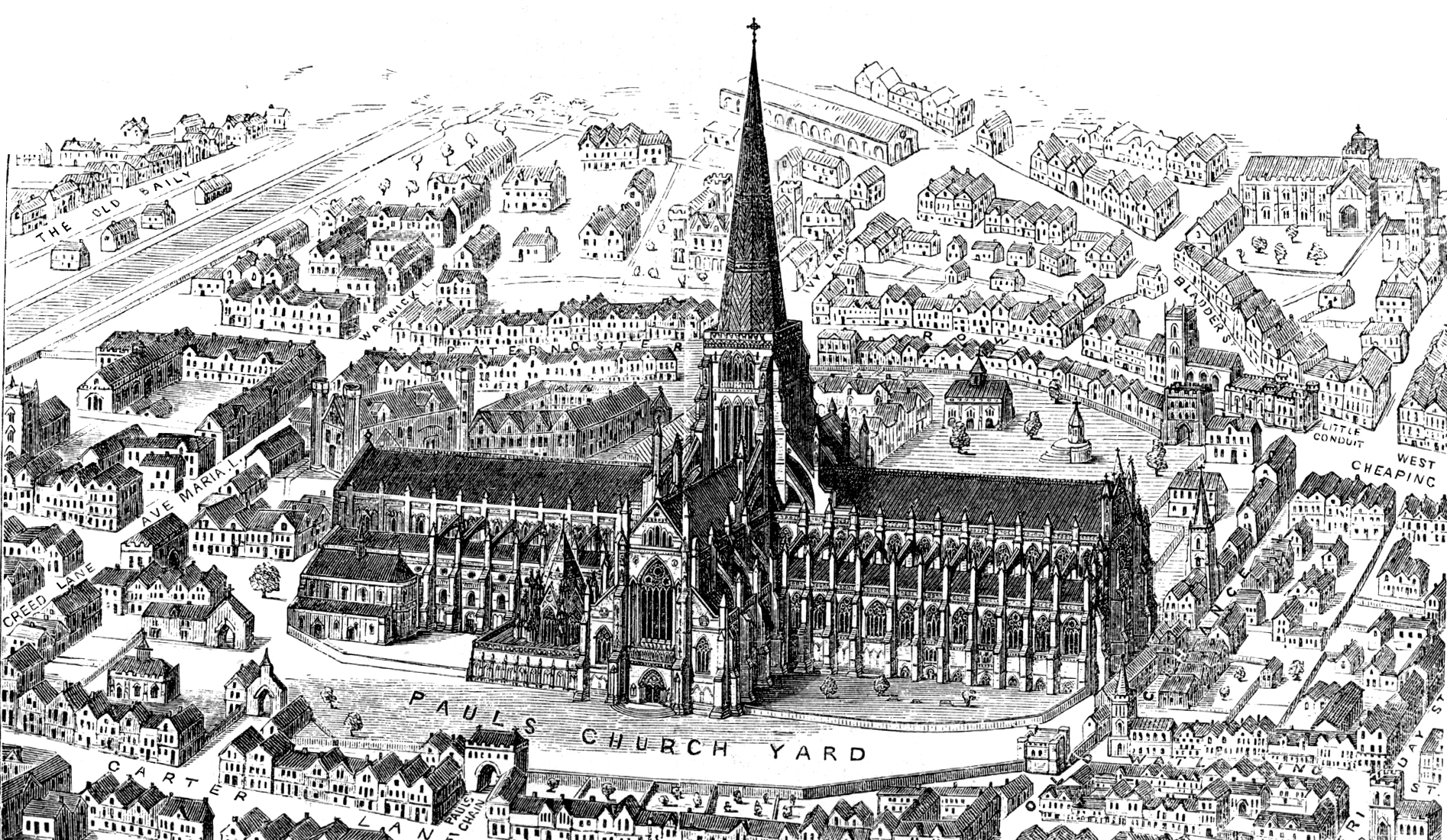

After James II, King of England/James VII, King of Scots, a son of King Charles I, lost his throne via the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the Jacobite (from Jacobus, the Latin for James) movement formed. The goal of the Jacobites was to restore the Roman Catholic Stuart King James II of England/VII of Scotland and his Roman Catholic heirs to the thrones of England and Scotland.

The current Jacobite pretender is Franz, Duke of Bavaria (born 1933), who is also the pretender to the throne of the Kingdom of Bavaria. Because Franz never married, his heir presumptive in the Jacobite line of succession is his younger brother, Prince Max, Duke in Bavaria (born 1937). Prince Max’s heir presumptive is his daughter Sophie, Duchess in Bavaria, Hereditary Princess of Liechtenstein, and then her eldest son, Prince Joseph Wenzel of Liechtenstein, who is second in the line of succession to the throne of Liechtenstein after his father, Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein.

- For more information, see The Jacobite Heritage

Why did James II, King of England/James VII, King of Scots lose his throne?

On February 6, 1685, Charles II, King of England, King of Scots died. Having no legitimate children, Charles was succeeded by his brother James, who reigned in England and Ireland as King James II, and in Scotland as King James VII. James and his second wife, Mary Beatrice of Modena, both Catholics, were crowned on April 23, 1685, following the Church of England rite but omitting Holy Communion. The previous day, they had been privately crowned and anointed in a Catholic rite in their private chapel at the Palace of Whitehall.

James II’s nephew James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth; Credit – Wikipedia

On June 11, 1685, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, the eldest of the illegitimate children of King Charles II, claimed the throne as the Protestant champion. Monmouth’s forces were defeated by the forces of his uncle, King James II, at the Battle of Sedgemoor. The Duke of Monmouth was beheaded for treason on July 15, 1685.

King James II was now set on a course of restoring Catholicism to England. He issued a Declaration of Indulgence removing restrictions imposed on those who did not conform to the Church of England. England might have tolerated King James II, knowing that his heirs were the Protestant daughters of his first wife, Anne Hyde, the future Queen Mary II and Queen Anne. However, on June 10, 1688, his Catholic second wife, Maria Beatrice of Modena, who had no surviving children, gave birth to a son, James Francis Edward, who would be raised Catholic. Immediately, false rumors swirled that the infant had been smuggled into the queen’s chambers in a warming pan.

William III, Prince of Orange, later King William III of England, James II’s nephew and son-in-law; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 5, 1688, William III, Prince of Orange, the nephew and son-in-law of King James II, landed in England vowing to safeguard the Protestant interest. He marched to London, gathering many supporters. James II panicked and sent his wife and infant son to France. He tried to flee to France about a month later but was captured. William III, Prince of Orange had no desire to make his uncle a martyr, so he allowed him to escape. James was received in France by his first cousin, King Louis XIV, who offered him a palace and a pension.

Back in England, Parliament refused to depose James II but declared that, having fled to France, James had effectively abdicated the throne and the throne had become vacant. James’s elder daughter Mary was declared Queen Mary II and was to rule jointly with her husband and first cousin, William III, Prince of Orange, who would be King William III. At that time, William, the only child of King James II’s deceased elder sister Mary, Princess Royal, Princess of Orange, was third in the line of succession after his wife and first cousin Mary and her sister Anne. This overthrow of King James II is known as the Glorious Revolution.

What happened to James II, King of England/James VII, King of Scots and his family?

Mary Beatrice and her son James Francis Edward Stuart; Credit – Wikipedia

James II, his wife Maria Beatrice of Modena, and his son James Francis Edward Stuart settled at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye in France, provided by James II’s first cousin, King Louis XIV of France, where a court in exile, composed mainly of Scots and English Catholics, was established. James II was determined to regain the throne and landed in Ireland with a French force in 1689. He was defeated by his nephew William III, King of England, at the Battle of the Boyne on July 1, 1690, and was forced to withdraw once again to France. James II spent the rest of his life in France, planning invasions that never happened. He died from a stroke on September 16, 1701, at St. Germain.

Battle of the Boyne between James II and his nephew William III, July 11, 1690; Credit – Wikipedia

Upon his father’s death, James Francis Edward was recognized by King Louis XIV of France as the rightful heir to the English and Scottish thrones. Spain, the Vatican, and Modena recognized him as King James III of England and VIII of Scotland and refused to recognize William III, Mary II, or Anne as legitimate sovereigns. As a result of James Francis Edward claiming his father’s lost thrones, he was attainted for treason in 1702, and his titles were forfeited under English law.

In 1708, James Francis Edward, with the support of King Louis XIV, attempted to land in Scotland, but the British Royal Navy intercepted the ships and prevented the landing. In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht forced King Louis XIV of France to recognize the British 1701 Act of Settlement, settling the succession on the Electress Sophia of Hanover, a granddaughter of James VI of Scotland and I of England, and her non-Roman Catholic heirs.

Upon the death of Queen Anne in August 1714, George, Elector of Hanover, son of Electress Sophia of Hanover, ascended the British throne as King George I. With the death of King Louis XIV in 1715, the French government found James Francis Edward an embarrassment, and he was no longer welcome in France. In 1715, Scottish Jacobites started “The ‘Fifteen” Jacobite rising, an unsuccessful attempt to put James III and VIII on the throne.

The Battle of Culloden; Credit – Wikipedia

After James Francis Edward failed to regain the throne, attention fell upon his son Charles Edward, The Young Pretender, whose Jacobite Rising of 1745 culminated in the final devastating loss for the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden. After the disastrous Battle of Culloden, there were no further Jacobite uprisings. James Francis Edward Stuart died at his home, the Palazzo Muti in Rome, on January 1, 1766, and was buried in the crypt of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican.

The Vatican had recognized James Francis Edward as King of England and Scotland as “James III and VIII” but did not give his son Charles Edward the same recognition. 67-year-old Charles Edward Stuart died of a stroke on January 31, 1788, at the Palazzo Muti in Rome. He was initially buried in the Cathedral of San Pietro in Frascati, Italy, where his brother Henry Benedict Stuart was Cardinal Bishop.

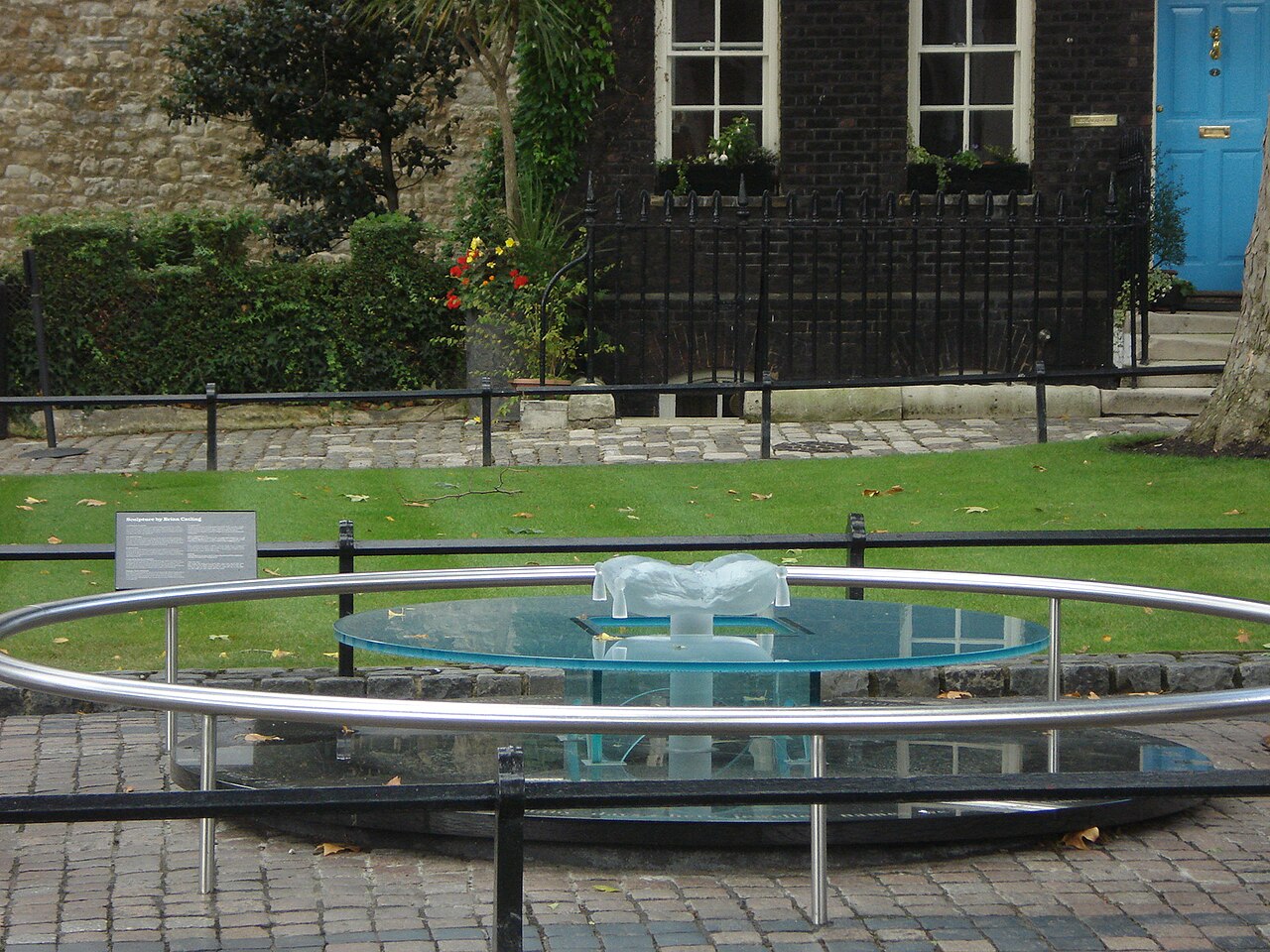

Memorial to the three Stuart pretenders, ‘James III’, and his sons, Charles Edward and Henry Benedict, above their place of interment in the crypt of St. Peter’s Basilica, in the Vatican; Credit – Wikipedia by Kim Traynor – Own work

Upon the death of his elder brother Charles Edward Stuart in 1788, Henry Benedict assumed the style “King Henry IX”, but no government considered him the legal King. After the French Revolution, Henry Benedict lost the funds that the French Royal Family had been paying his exiled family and any French property he owned, causing him financial problems. In 1800, King George III granted Henry Benedict a pension of £4,000 per year. For many years, the British government had promised to return the dowry of his grandmother Maria Beatrice of Modena, but never did so. Henry Benedict considered the £4,000 per year an installment on money legally owed him. Henry Benedict Stuart died on July 13, 1807, at the age of 82. He was buried in the crypt at St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican, where his father had been buried, and Charles Edward’s remains were transferred to the same crypt in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican.

The Jacobite Pretenders

In 1807, with the extinction of the Stuart line descended from James II, King of England/James VII, King of Scots, the Jacobite succession proceeded to the House of Savoy. The Jacobite pretender became Carlo Emanuele IV, King of Sardinia, the senior surviving descendant of Henrietta of England, Duchess of Orléans, the younger sister of James II/VII. The Jacobite succession proceeded to the House of Austria-Este and then to the House of Wittelsbach. It likely will proceed to the House of Liechtenstein.

However, unlike the Stuart pretenders, none of the later pretenders have claimed the thrones of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom or incorporated the arms of these countries in their coat-of-arms. Nevertheless, since the 19th century, there have been groups advocating the restoration of the Jacobite succession to the throne.

Charles I of England → his daughter Henrietta of England, Duchess of Orléans → her daughter Anne Marie d’Orléans, Queen of Sardinia → her son Carlo Emanuele III, King of Sardinia → his son Vittorio Amadeo III, King of Sardinia → his son Carlo Emanuele IV, King of Sardinia → his brother Vittorio Emanuele I, King of Sardinia → his daughter Maria Beatrice of Savoy, Duchess of Modena and Reggio → her son Francesco V, Duke of Modena and Reggio → his niece Maria Theresa of Austria-Este, Queen of Bavaria → her son Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria → his son Albrecht, Duke of Bavaria → his son Franz, Duke of Bavaria

House of Stuart

James II, King of England/James VII, King of Scots; Credit – Wikipedia

- James II of England & James VII of Scotland (1633 – 1701)

- Reigned: February 6, 1685 – December 11, 1688

- Claim: December 11, 1688 – September 16, 1701

- James lawfully succeeded his brother, King Charles II, to the thrones of England and Scotland on February 6, 1685, as Charles II did not have legitimate children. When James fled England in 1688, the English Parliament declared that he had abdicated, and the Scottish Convention of Estates declared he had forfeited his crown. However, James and his supporters denied that he had abdicated and claimed that the declaration of forfeiture had been by an illegal Scottish Convention. They maintained that James continued to be the rightful king.

********************

James Francis Edward Stuart; Credit – Wikipedia

- James Francis Edward Stuart (1688 – 1766)

- Son of James II of England & James VII of Scotland

- “James III & James VIII”

- The Old Pretender

- Claim: September 16, 1701 – January 1, 1766 as James II/VII’s only surviving legitimate son

********************

Charles Edward Stuart; Credit – Wikipedia

- Charles Edward Stuart (1720 – 1788)

- Elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart

- “Charles III”

- The Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie

- Claim: January 1, 1766 – January 31, 1788 as James Francis Stuart’s elder son

********************

Henry Benedict Stuart; Credit – Wikipedia

- Cardinal Henry Benedict Stuart (1725 – 1807)

- Younger son of James Francis Edward Stuart

- “Henry IX & Henry I”

- Claim: January 31, 1788 – July 13, 1807 as the only brother of Charles Edward Stuart. Henry Benedict was the last surviving legitimate descendant of James II/VII.

********************

House of Savoy

Carlo Emanuele IV, King of Sardinia; Credit – Wikipedia

- Carlo Emanuele IV, King of Sardinia (1751 – 1819)

- Great-great-grandson of Henrietta of England, Duchess of Orléans, daughter of King Charles I of England

- “Charles IV”

- Claim: July 13, 1807 – October 6, 1819 as the senior surviving descendant of Henrietta of England, Duchess of Orléans, the youngest sister of James II/VII and the daughter of King Charles I.

- Henry Benedict died childless, and no other legitimate descendants of James II/VII survived. At Henry Benedict’s death, there were no surviving siblings of King James II/VII, son of King Charles I, or their legitimate descendants, except for the descendants of his youngest sister Henrietta, Duchess of Orléans. Henrietta married Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, and they had one son who died in infancy and two daughters. Only their daughter Anne Marie d’Orléans, who married Vittorio Amedeo II, King of Sardinia, had children.

********************

Vittorio Emanuele I, King of Sardinia; Credit – Wikipedia

- Vittorio Emanuele I, King of Sardinia (1759 – 1824)

- Brother of Carlo Emanuele IV, King of Sardinia

- “Victor”

- Claim: October 6, 1819 – January 10, 1824 as the next eldest brother of his predecessor, Carlo Emanuele, who had died childless

********************

Maria Beatrice of Savoy, Duchess of Modena; Credit – Wikipedia

- Maria Beatrice of Savoy, Duchess of Modena (1792 – 1840)

- Eldest surviving daughter of Vittorio Emanuele I, King of Sardinia

- “Mary II”

- Claim: January 10, 1824 – September 15, 1840 as the eldest surviving daughter of her predecessor Vittorio Emanuele, who had no surviving sons

********************

House of Austria-Este

Francesco V, Duke of Modena; Credit – Wikipedia

- Francesco V, Duke of Modena (1819 – 1875)

- Eldest son of Maria Beatrice of Savoy, Duchess of Modena

- “Francis I”

- Claim: September 15, 1840 – November 20, 1875 as the eldest son of his predecessor Maria Beatrice

********************

Maria Theresa of Austria-Este, Queen of Bavaria; Credit – Wikipedia

- Maria Theresa of Austria-Este, Queen of Bavaria (1849 – 1919)

- Niece of Francesco V, Duke of Modena

- “Mary III”

- Claim: November 20, 1875 – February 3, 1919 as the niece of her predecessor, Francesco V, who died childless. She was the only child of Francesco’s only brother Archduke Ferdinand Karl Viktor of Austria-Este, who pre-deceased Francesco.

********************

House of Wittelsbach

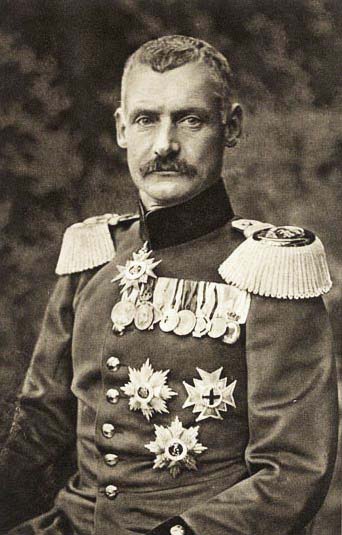

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria; Credit – Wikipedia

- Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria (1869 – 1955)

- Eldest son of Maria Theresa of Austria-Este, Queen of Bavaria

- “Robert I & IV”

- Claim: February 3, 1919 – August 2, 1955 as the eldest son of his predecessor Maria Theresa.

********************

Albrecht with his younger half-brother, Prince Heinrich; Credit – Wikipedia

- Albrecht, Duke of Bavaria (1905 – 1996)

- Eldest surviving son of Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria

- “Albert”

- Claim: August 2, 1955 – July 8, 1996, as the eldest surviving son of his predecessor Rupprecht.

********************

Franz, Duke of Bavaria; Credit – Wikipedia by Christoph Wagener

- Franz, Duke of Bavaria (born 1933)

- Eldest son of Albrecht, Duke of Bavaria

- “Francis II”

- Claim: July 8, 1996 – present pretender as the eldest son of his predecessor, Albrecht.

- Franz’s heir presumptive is his younger brother, Prince Max, Duke in Bavaria. Prince Max’s heir presumptive is his daughter Sophie, Duchess in Bavaria, Hereditary Princess of Liechtenstein, and then her eldest son, Prince Joseph Wenzel of Liechtenstein, who is second in the line of succession to the throne of Liechtenstein after his father, Alois, Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein. Franz is also the pretender to the throne of the Kingdom of Bavaria.

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Jacobite succession – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacobite_succession> [Accessed 22 June 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. Charles Edward Stuart, The Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/charles-edward-stuart/> [Accessed 22 June 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. Cardinal Henry Benedict Stuart. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/cardinal-henry-benedict-stuart/> [Accessed 22 June 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2017. King James II of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-james-ii-of-england/> [Accessed 22 June 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. James Francis Edward Stuart, The Old Pretender. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/james-francis-edward-stuart-the-old-pretender/> [Accessed 22 June 2021].

- Jacobite.ca. 2021. The Jacobite Heritage. [online] Available at: <http://www.jacobite.ca/> [Accessed 22 June 2021].