by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

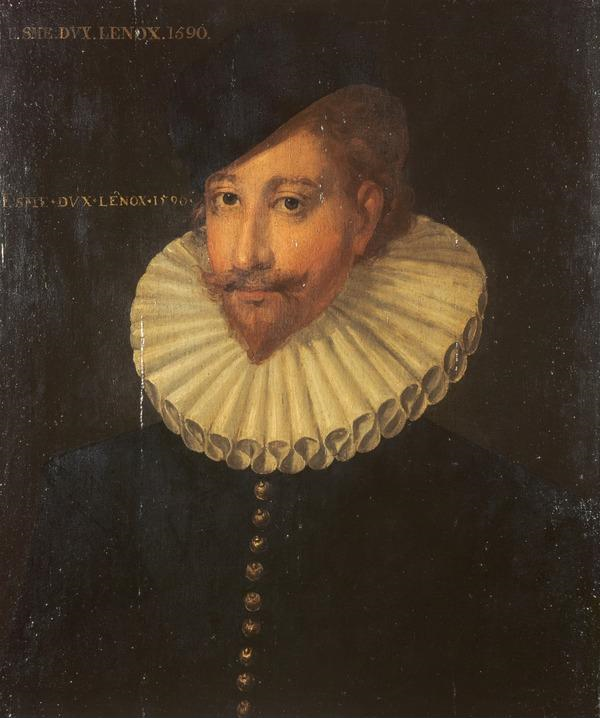

William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland; Credit – Wikipedia

Favorite: a person treated with special or undue favor by a king, queen, or another royal person

William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland was born Hans Willem Bentinck on July 20, 1649, in Diepenheim, Overijssel, Dutch Republic, now in the Netherlands. He was the fourth of the eight children and the third of the three sons of Berent Bentinck, 6th Baron Bentinck (1597 – 1668) and Anna van Bloemendale (1622 – 1685). The Bentinck family is an old Dutch noble family whose noble rank can be traced to the 14th century.

Bentinck had seven siblings:

- Hendrik Bentinck, 7th Baron Bentinck (1640 – 1691), married Ida Magdalena van Ittersum, had three daughters

- Eusebius Bentinck, 8th Baron Bentinck (1643 – 1710), married (1) Elizabeth de Brakell, had two sons and one daughter (2) Hendrina Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, no children, died two months after her wedding

- Eleonore Bentinck (1644 – 1710), married Robert van Ittersum, Baron Nijenhuis, no children?

- Isabelle Bentinck (1651 – 1687), married Alexander Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Baron van De Engelenburg, no children, died five months after her wedding

- Anna Bentinck (1652 – 1721), married Dirk Borre van Amerongen, had two daughters

- Agnes Bentinck (1654 – 1722), unmarried?

- Johanna Bentinck (1597 – 1668), unmarried?

Willem III, Prince of Orange, 1661; Credit – Wikipedia

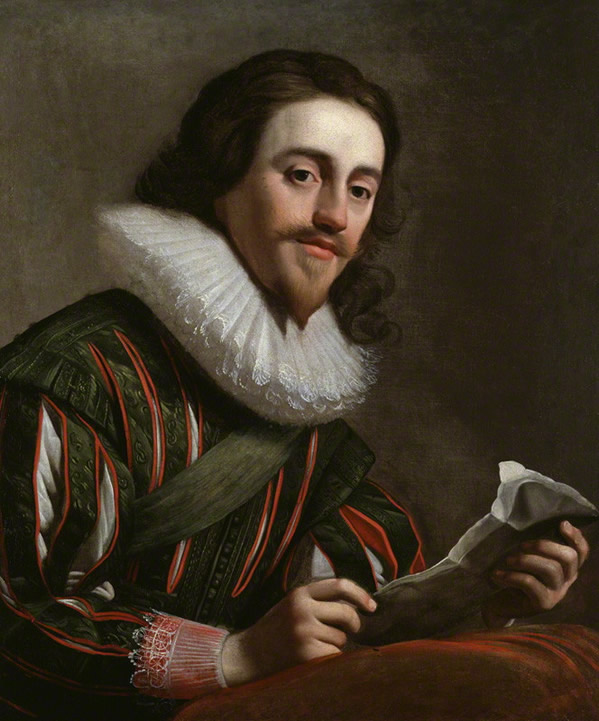

In 1664, fifteen-year-old Hans Willem Bentinck came to the court of fourteen-year-old Willem III, Prince of Orange, as a page. Willem III was the only child of Willem II, Prince of Orange and Mary, Princess Royal, the eldest daughter of King Charles I of England. Willem III’s father died at age 24 of smallpox eight days before Willem III’s birth, so when he was born on November 14, 1650, Willem III succeeded to his father’s titles. Being the grandson of King Charles I of England, Willem III was also in the line of succession to the English throne and eventually co-reigned as King William III of England with his wife and first cousin Queen Mary II of England.

In 1672, Bentinck became Willem III’s chamberlain. Along with his role at the court where he was an important advisor for Willem III, Bentinck also had a military career. When Willem III became ill with smallpox in 1675, Bentinck cared for him for sixteen days. When Willem III recovered, Bentinck fell ill with smallpox but recovered in time to accompany Willem III on a military campaign that year. Sadly, smallpox caused much personal loss for Willem III. His father Willem II, Prince of Orange, his mother Mary, Princess Royal, Princess of Orange, and his wife Queen Mary II of England all died from smallpox.

The future Queen Mary II of England in 1677; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1677, Bentinck was Willem III’s special envoy to England where he sought the support of Willem’s uncle King Charles II of England in the Dutch Republic’s struggle against France. At the same time, Bentinck negotiated a marriage for Willem III with his first cousin Mary, the elder surviving daughter of James, Duke of York, later King James II of England, and his first wife Anne Hyde. 27-year-old Willem and a weepy 15-year-old Mary, prodded on by their uncle King Charles II, were married at St. James’ Palace in London, England on November 4, 1677. Bentinck served as Willem III’s best man.

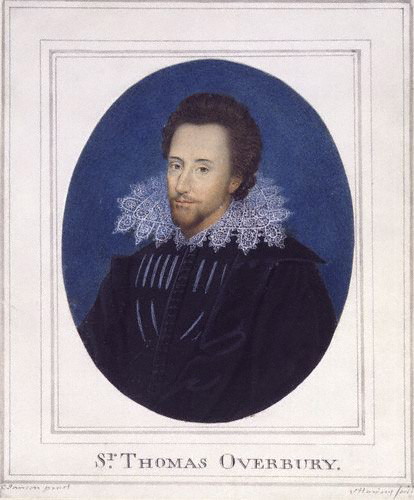

Bentinck’s first wife Anne Villiers; Credit – Wikipedia

Bentinck’s first wife Anne Villiers (circa 1651 – 1688) was the eldest child of Sir Edward Villiers and his wife Lady Frances Howard, daughter of Theophilus Howard, 2nd Earl of Suffolk. Anne’s mother had been the governess to Willem III’s new wife Mary and her younger sister, the future Queen Anne, and she used her position at court to secure positions in Mary’s new household for her daughters. Anne Villiers and her sisters Elizabeth and Katherine, were among the maids of honor who accompanied Mary to The Hague in the Dutch Republic, now in the Netherlands, to serve the new Princess of Orange. The three Villiers sisters were the first cousins of Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland, born Barbara Villiers, a mistress of King Charles II of England. Their fathers were brothers.

Bentinck and Anne Villiers became acquainted and on February 1, 1678, they were married. They are ancestors of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom through her mother’s family, specifically through her maternal grandmother born Cecilia Cavendish-Bentinck. Five months after giving birth to her last child, Anne died on November 30, 1688, in The Hague, Dutch Republic, now in the Netherlands.

Bentinck and Anne had seven children:

- Lady Mary Bentinck (1679 – 1726), married (1) Algernon Capell, 2nd Earl of Essex, had one son and two daughters (2) Sir Conyers D’Arcy, no children

- Willem Bentinck (1681 – 1688), died in childhood

- Henry Bentinck, 1st Duke of Portland (1682 – 1726), married Lady Elizabeth Noel, had two sons and three daughters

- Lady Anna Bentinck (1683 – 1763), married Arent van Wassenaar, Baron van Wassenaar, had at least one daughter

- Lady Frances Bentinck (1684 – 1712), married William Byron, 4th Baron Byron, had three sons and one daughter who all died in childhood

- Lady Eleonora Bentinck (1687 – ?)

- Lady Isabella Bentinck (1688 – 1728), married Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull, had two daughters

Anne’s sister Elizabeth Villiers; Credit – Wikipedia

Anne’s sister Elizabeth Villiers became the mistress of Willem III, and reportedly, she was his only mistress. In 1679, when Willem III made his first advances to Elizabeth, she tried to discourage him. However, by 1680, Elizabeth was his mistress, rumors of the affair reached Paris, and Mary was probably aware of her husband’s relationship with Elizabeth. In 1685, Mary’s father, now King James II of England, hoping to break up his daughter’s marriage with Willem III, had encouraged others to relay gossip from Mary and Willem III’s household to him. Through the meddling of King James II, Elizabeth and Willem III’s affair became public knowledge and Elizabeth was sent back to England. To stop rumors continuing in England, Elizabeth’s father begged Willem III and Mary to allow Elizabeth to return to The Hague. Elizabeth was permitted to return but Mary refused to receive her. Elizabeth then went to live with her sister Katherine who had married and settled in The Hague. Bentinck had forbidden his wife Anne to socialize with her sister Elizabeth. Meanwhile, the affair between Elizabeth and Willem III continued and was to last until 1695, a total of fifteen years.

The Landing of His Royal Highness in England by Bastiaen Stopendael (Stoopendael), or by Daniel Stopendael (Stoopendael) etching, circa 1689 NPG D22617 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Following his initial visit to England in 1677, Bentinck was sent on many other diplomatic missions to England, resulting in the development of a strong and influential network of contacts within English political circles. As a result, Bentinck was to play a key role in the planning and execution of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, following the birth of a Catholic heir James Francis Edward Stuart to Maria Beatrice of Modena, the second wife of King James II of England, Mary’s father and Willem III’s uncle. Willem III, Prince of Orange landed in England vowing to safeguard the Protestant interest. He marched to London, gathering many supporters. James II panicked and sent his wife and infant son to France. James later fled to France where his first cousin King Louis XIV of France offered him a palace and pension. Parliament refused to depose James II but declared that having fled to France, James had effectively abdicated the throne and therefore, the throne had become vacant. James’s elder daughter Mary was declared Queen Mary II and she was to rule jointly with her husband Willem, whose name would be anglicized to William. He would reign in England as King William III but he remained Willem III, Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic.

Quartered arms of William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland, KG, PC; Credit – By Rs-nourse – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68789077

Having supported King William III throughout his efforts to secure the English throne, and after accompanying him to England, Bentinck was generously rewarded. Parliament passed an act of naturalization so that he and his children would be British subjects. He was created Earl of Portland, Viscount Woodstock, and Baron Cirencester. With these titles came significant estates, including Theobalds House in Hertfordshire, England. Bentinck was appointed Groom of the Stole, Keeper of the Privy Purse, and a Privy Councilor, and he remained William III’s closest advisor. In 1697, William III created Bentinck a Knight of the Order of the Garter.

In late December 1694, when Mary was very ill with smallpox, Bentinck was one of the two people William III would see. On December 28, 1694, Queen Mary II of England, aged only 32, died of smallpox at Kensington Palace. When Mary’s grief-stricken husband collapsed at her death bed, it was Bentinck who carried the nearly insensible William from the room.

Bentinck was responsible for overseeing affairs in Scotland and played an influential role in English politics. His main achievements were diplomatic. In 1697, Bentinck played a major role in securing the Treaty of Ryswick, ending the Nine Years’ War (1688 – 1697) between France and the Dutch Republic. He was active in addressing the crisis of the Spanish succession through the Treaty of The Hague (1698) and the Treaty of London (1700) and became William III’s ambassador to France.

Bentinck became very jealous of the rising influence of another Dutchman Arnold Joost van Keppel. Keppel was created Earl of Albemarle by William III and emerged as the second favorite. Because of this, in 1700, Bentinck resigned all his offices in the royal household. However, he never lost the esteem of King William III who continued to trust him and use him as an advisor.

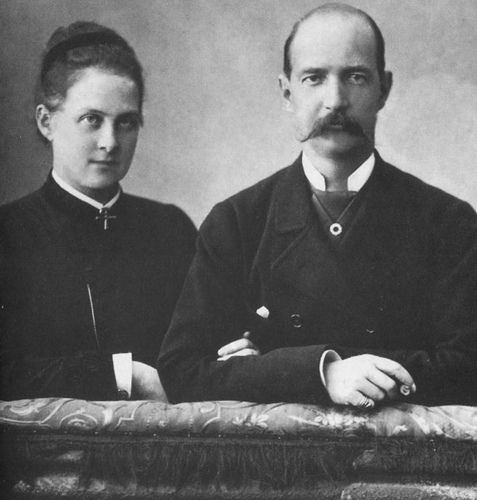

Jane Martha Temple, Bentinck’s second wife; Credit – Wikipedia

On May 12, 1700, 51-year-old Bentinck married again to 28-year-old Jane Martha Temple (1672 – 1751), daughter of Sir John Temple, and widow of John Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley of Stratton. He spent his final years consolidating his estates and adding to his family.

Bentinck and Jane had six children:

- Lady Sophia Bentinck (1701 – 1741), married Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Kent, had one son and one daughter

- Lady Elizabeth Bentinck (1703 – 1765), married Reverand The Honorable Henry Egerton, Bishop of Hereford, had five sons and one daughter

- The Honorable Willem Bentinck, 1st Count Bentinck (1704 – 1774), married Charlotte Sophie, Countess von Aldenburg, had two sons, the title of Count Bentinck of the Holy Roman Empire, was created for Willem as the second surviving son

- Lady Harriet Bentinck (1705 – 1792), married James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Clanbrassill, had one son and one daughter

- The Honorable Charles Bentinck (1708 – 1779), who married Lady Margaret Cadogan, daughter of William Cadogan, 1st Earl Cadogan, children ?

- Lady Barbara Bentinck (1709 – 1736), married Francis Godolphin, 2nd Baron Godolphin, no children

On February 20, 1702, King William III went riding at Hampton Court Palace. The horse stumbled on a molehill and fell. William tried to pull the horse up by the reins, but the horse’s movements caused William to fall on his right shoulder. His collarbone was broken and was set by a surgeon, but instead of resting, William insisted on returning to Kensington Palace that evening by coach. Bentinck called on William every day as he recovered. However, a week after the fall, the fracture was not healing well and William’s right hand and arm were puffy and did not look right which probably meant an infection developed. His condition continued to worsen and by March 3, William had a high fever and had difficulty breathing. By March 7, the doctors knew that William was dying and he began to say goodbye to his friends and advisors. By the time Bentinck arrived on March 8, 1702, William had lost his power of speech but with a look, he beckoned Bentinck to his bedside. Bentinck bent down and put his ear to William’s mouth but could only distinguish a few words of William’s incoherent speech. William then took Bentinck’s hand and placed it against his heart. Then William’s head fell back, he closed his eyes, took two or three breaths, and died.

William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland; Credit – Wikipedia

William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland, aged 60, died on November 23, 1709, at Bulstrode Park, one of his principal residences, in Buckinghamshire, England. He was buried at Westminster Abbey in London, England, in the Ormond Vault at the eastern end of Henry VII’s Chapel. He has no monument but his name and date of death were added to the vault stone in the late 19th century. The Ormond Vault is now located in the Royal Air Force Chapel at Westminster Abbey and a carpet permanently covers the vault-stone with the inscribed names.

Bentinck’s second wife Jane survived him by 42 years, dying on June 26, 1751, in London, England, at the age of 79. She was buried in the cemetery at St. Mary the Virgin Church in Walthamstow, London, England.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Bentinck,_1st_Earl_of_Portland> [Accessed 30 January 2021].

- Genealogics.org. 2021. Berent Bentinck, Heer van Diepenheim : Genealogics. [online] Available at: <https://www.genealogics.org/getperson.php?personID=I00003344&tree=LEO> [Accessed 30 January 2021].

- Nl.wikipedia.org. 2021. Hans Willem Bentinck. [online] Available at: <https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Willem_Bentinck> [Accessed 30 January 2021].

- Nottingham.ac.uk. 2021. Biography of Hans William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland (1649-1709) – The University of Nottingham. [online] Available at: <https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/collectionsindepth/family/portland/biographies/biographyofhanswilliambentinck,1stearlofportland(1649-1709).aspx> [Accessed 30 January 2021].

- Sir Hans Willem Bentinck, 1. and Diepenheim, N., 2021. Hans Willem Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland. [online] geni_family_tree. Available at: <https://www.geni.com/people/Sir-Hans-Willem-Bentinck-1st-Earl-of-Portland/6000000003265080482> [Accessed 30 January 2021].

- Thepeerage.com. 2021. Person Page – Hans William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland. [online] Available at: <http://www.thepeerage.com/p965.htm#i9646> [Accessed 30 January 2021].

- Van Der Kiste, John, 2003. William and Mary. Phoenix Hill: Sutton Publishing.

- Westminster Abbey. 2021. William & Henry Bentinck | Westminster Abbey. [online] Available at: <https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-commemorations/commemorations/william-henry-bentinck> [Accessed 30 January 2021].