by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex; Credit – Wikipedia

Favorite: a person treated with special or undue favor by a king, queen, or another royal person

A favorite of Queen Elizabeth I but beheaded for treason, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex was the great-grandson of Mary Boleyn, sister of Anne Boleyn, and the stepson of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, Queen Elizabeth I’s favorite. Born November 10, 1565, at Netherwood near Bromyard, Herefordshire, England. Robert was the eldest of the three sons and the eldest of the five children of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex (1541 – 1576), and Lettice Knollys (1543 – 1634). Robert’s father was an army general in service to Queen Elizabeth I. Robert’s mother Lettice Knollys was the daughter of Sir Francis Knollys, who was a courtier in the service of King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, and Queen Elizabeth I, and Catherine Carey. Catherine Carey was the daughter of Mary Boleyn, the sister of Anne Boleyn, King Henry VIII’s second wife, and the mother of Queen Elizabeth I. This made Lettice Knollys the first cousin once removed of Queen Elizabeth I and therefore her son Robert was Elizabeth’s first cousin twice removed.

Robert’s sisters Dorothy and Penelope Devereux; Credit – Wikipedia

Robert had four younger siblings:

- Sir Walter Devereux (1569 – 1591), married Margaret, Dakyns, no children, killed at the Siege of Rouen

- Penelope Devereux (1563 – 1607), married (1) Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick, 3rd Baron Rich, had seven children, divorced due to Penelope’s adultery (2) Charles Blount, 1st Earl of Devonshire, had four children out of wedlock who were never legitimized

- Dorothy Devereux (circa 1564 – 1619), married (1) Sir Thomas Perrot, had five children (2) Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, had four children

- Francis Devereux (born and died 1572)

Robert’s father died in 1576, and the eleven-year-old became the 2nd Earl of Essex and the ward of William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I. On September 21, 1578, Robert got a stepfather when his mother married Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, Queen Elizabeth I’s long-time favorite and Robert’s godfather. Dudley feared Elizabeth I’s reaction to his marriage and insisted it be kept secret. However, Elizabeth I found out about the marriage two months later. She banished her cousin Lettice permanently from court, never forgave her, and never accepted the marriage. Although Dudley remained at court, he was alternately humiliated in public by Elizabeth and treated as fondly as always.

Robert had one half-brother who died in childhood from his mother’s second marriage:

- Robert Dudley, Lord Denbigh (1581 – 1584)

Robert Dudley had much influence on his godson and stepson Robert Devereux. Robert served in the military under his stepfather’s command in the Netherlands. Several years before he died in 1588, Dudley introduced Robert to the Elizabethan court, and Elizabeth I increasingly became interested in the young man. Robert spent much time in the company of Elizabeth I and succeeded his stepfather in royal favor. Although Elizabeth I was thirty-two years older than Robert, she found it very pleasant to be adored by such a young man. In June 1587, Robert replaced Dudley as Master of the Horse. After Dudley died in 1588, Elizabeth I transferred Dudley’s royal monopoly on sweet wines to Robert, providing him with lucrative revenue. In 1593, Robert was made a member of the Privy Council.

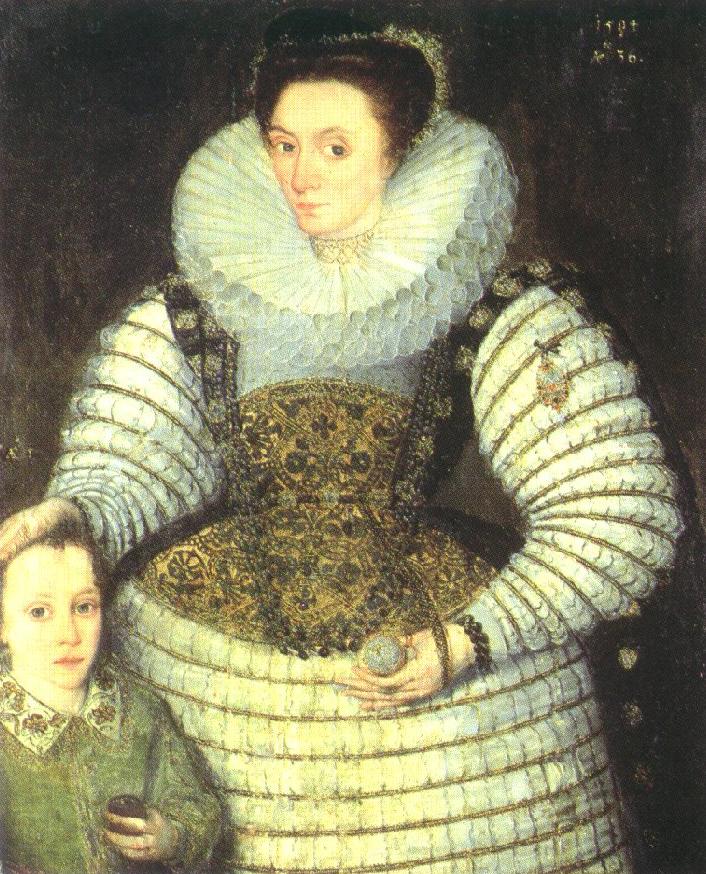

Frances Walsingham and her son Robert; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1590, Robert married Frances Walsingham, the only surviving child of Sir Francis Walsingham, Secretary of State and spymaster for Queen Elizabeth I, and Ursula St. Barbe. The marriage greatly displeased Queen Elizabeth I because the couple had not asked for permission beforehand, but she forgave them relatively quickly.

Robert and Frances had five children:

- Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex (1592 – 1646), married (1) Frances Howard, no children, marriage annulled (2) Elizabeth Paulet, no children

- Penelope Devereux (1593/4 – 1599), died in childhood

- Henry Devereux (born and died 1596), died in infancy

- Frances Devereux (1599 – 1674), married William Seymour, 2nd Duke of Somerset, had eight children

- Dorothy Devereux (1600 – 1636), married Sir Henry Shirley, 2nd Baronet, had three children

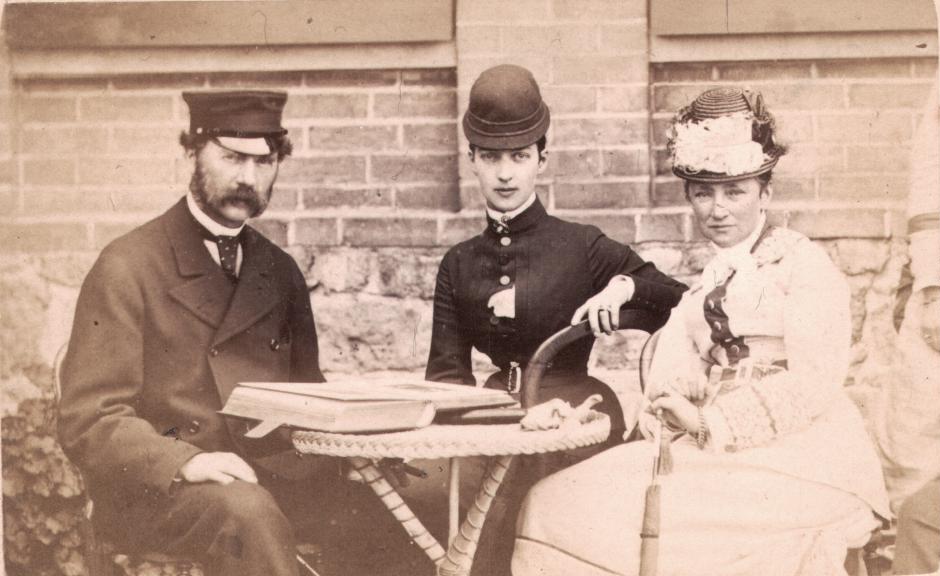

Robert in 1590; Credit – Wikipedia

Robert had a petulant nature, acted on whims, and often acted disdainfully and disrespectfully. His behavior would ultimately lead to his downfall. At court, he dueled with Sir Walter Raleigh, among others, which displeased Elizabeth I. In 1591, Robert was given command of an army that was to come to the aid of Henri IV, King of France but he defied Elizabeth’s instructions. In the summer of 1596, Robert managed to easily take the Spanish port of Cadiz. However, because the Spanish were able to burn their ships before the attack, there was nearly no loot but Robert’s bold act made him famous throughout Europe. However, the next year, an expedition to the Azores with Sir Walter Raleigh was a complete failure.

In 1599, Robert reluctantly accepted the post of Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. At that time, the Irish revolutionary Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone was rebelling against the English rule in Ireland. After several costly battles and an armistice that was disadvantageous for England, Robert disregarded an explicit order from Elizabeth I to remain at his post in Ireland. He left Ireland in September 1599 and reached London four days later where he gained access to the chambers of the not-yet-fully-dressed Queen Elizabeth I. After interrogation by the Privy Council, Robert was placed under house arrest for ten months.

Robert was released from house arrest in August 1600 but the source of his income, the monopoly on sweet wines, was not renewed. His financial situation became more and more desperate. Robert had inherited large debts from his father, and he had amassed his own large debts. Essex House, Robert’s London mansion, became a meeting place for people who were upset with Elizabeth I’s government. On February 3, 1601, five conspiracy leaders met at the home of Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton. Hoping to avoid suspicion, Robert was not present. The group discussed Robert’s proposals for seizing the court, the Tower of London, and the City of London. Their goal was to force Queen Elizabeth I to change the leaders in her government, particularly Robert Cecil, Secretary of State.

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton; Credit – Wikipedia

On February 8, 1601, four messengers including Lord Keeper Thomas Egerton,1st Viscount Brackley came to Essex House in the name of Queen Elizabeth I to try to persuade Robert to surrender. Robert seized the four messengers and held them hostage. Then Robert and about 200 followers made their way to the City of London. Meanwhile, Robert Cecil sent a warning to the Lord Mayor of London denouncing Robert as a traitor and ordered the heralds to spread the warning throughout London. Once the word traitor was used, many of Robert’s followers disappeared, and none of the citizens joined him as he had expected. Robert’s position was desperate, and he returned to Essex House. When he got there, he found the hostages gone. Soldiers under Lord High Admiral Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, besieged Essex House and rescued the hostages. By that evening, after burning incriminating evidence, Robert surrendered and was arrested along with the Earl of Southampton and the other conspirators.

On February 19, 1601, Robert and Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton were tried on charges of treason. The trial lasted only a day and it was no surprise that the verdict was guilty. Robert had burned incriminating evidence to save his followers before his arrest but he was convinced by a minister he needed to reveal the identity of his conspirators to save his soul. He revealed everyone involved including his sister Penelope Blount, Countess of Devonshire on whom he put a great deal of the blame but no action was taken against her. Robert, the Earl of Southampton, and four others were sentenced to death. Other conspirators were fined. Through the efforts of Robert Cecil, Southampton’s sentence was reduced to life imprisonment. Southampton and one other conspirator remained imprisoned in the Tower of London and were freed when King James I succeeded to the throne in 1603 upon the death of Queen Elizabeth I.

Site of the scaffold in front of St. Peter’s Chapel at the Tower of London; Credit – By August – originally posted to Flickr as Off with their Heads!, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4530234

Robert’s wife Frances attempted to see Queen Elizabeth I to plead for clemency but the queen refused to see her. On February 25, 1601, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, aged 34, was beheaded on Tower Green within the Tower of London. Beheading in the privacy of Tower Green was considered a privilege of rank and those executed there were spared insults from the jeering crowd. He was buried in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula at the Tower of London. Robert’s conviction for treason meant that his earldom was forfeit and his son did not inherit the title. However, after Queen Elizabeth I’s death, King James I reinstated the earldom in favor of Robert’s disinherited son, Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex.

Plaque in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula; Credit – https://elizregina.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/q1-i-was-here.jpg

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2020. Robert Devereux, 2. Earl Of Essex. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Devereux,_2._Earl_of_Essex> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Essex’s Rebellion. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essex%27s_Rebellion> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Robert Devereux, 2Nd Earl Of Essex. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Devereux,_2nd_Earl_of_Essex> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Henry Wriothesley, 3Rd Earl Of Southampton. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Wriothesley,_3rd_Earl_of_Southampton> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Lettice Knollys. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lettice_Knollys> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- Erickson, Carolly, 1983. The First Elizabeth. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

- es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Devereux,_II_conde_de_Essex

- Flantzer, Susan, 2015. Queen Elizabeth I Of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/queen-elizabeth-i-of-england/> [Accessed 29 November 2020].

- Weir, Alison, 2011. The Children Of Henry VIII. New York: Random House Publishing Group.

- Weir, Alison., 2013. The Life Of Elizabeth I. New York: Random House Publishing Group.