by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2015

Queen Elizabeth I of England; Credit – Wikipedia

The last monarch of the House of Tudor, Queen Elizabeth I is number six on the list of the top ten longest-reigning British monarchs. She became queen at the age of 25 on November 17, 1558, and reigned for 44 years, 127 days until her death at age 69 on March 24, 1603. During Elizabeth’s reign, called the Elizabethan Age, the Church of England took its final form, a middle path between Catholicism and Reform Protestantism, William Shakespeare created numerous works, modern science had its birth based upon Francis Bacon‘s inductive method for scientific inquiry, Francis Drake sailed around the world, and the first colony in America was founded and named Virginia in honor of Elizabeth the Virgin Queen.

Elizabeth was born on September 7, 1533, at Greenwich Palace. She was the only surviving child of her parents, King Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn. Henry VIII was bitterly disappointed by the birth of a daughter. He already had letters to foreign courts prepared to announce a prince’s birth and there was only enough room to add one “s”. Elizabeth, named after her grandmothers Elizabeth of York, daughter of King Edward IV and wife of King Henry VII, and Lady Elizabeth Howard, daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk, was proclaimed heir presumptive to the throne displacing her elder half-sister Mary.

Henry VIII still wanted a male heir. After Elizabeth’s birth, Anne Boleyn had a stillborn son and then miscarried a son, and that sealed Anne’s fate. Henry was determined to be rid of Anne and her fall and execution were engineered by Thomas Cromwell. Anne was found guilty of the fabricated charges of adultery, incest, and high treason, and on May 19, 1536, was beheaded at the Tower of London. Elizabeth was not yet three years old.

The Second Succession Act in 1536 declared Henry’s children by Jane Seymour, his third wife, to be next in the line of succession and declared both Mary and Elizabeth illegitimate and excluded from the succession. Catherine Parr, Henry VIII’s sixth and final wife, was partially responsible for reconciling Henry with his daughters Mary and Elizabeth and also developed a good relationship with Henry’s son Edward. She was also influential in Henry’s passing of the Third Succession Act in 1543 which restored his daughters Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession to the throne.

Elizabeth had one elder half-sister and one younger half-brother:

- Mary I, Queen of England (1516 – 1558), married King Philip II of Spain, no children

by Jane Seymour:

- Edward VI, King of England (1537 – 1553), unmarried

Elizabeth had her own household and was well-educated. Her most influential governess was Catherine Champernowne, better known by her later, married name of Catherine “Kat” Ashley, who was appointed Elizabeth’s governess in 1537. She taught Elizabeth astronomy, geography, history, mathematics, French, Flemish, Italian and Spanish. In addition, she taught Elizabeth non-academic pursuits such as needlework, embroidery, dancing, and riding. When Elizabeth became queen in 1558, Kat Ashley was appointed First Lady of the Bedchamber and when she died in 1565, Elizabeth was heartbroken.

In 1544, William Grindal became Elizabeth’s tutor and helped her progress in Latin and Greek. When Grindal died of the plague in 1548, Roger Ascham who lectured and taught Greek at St John’s College, Cambridge, took over as Elizabeth’s tutor. Ascham said of Elizabeth, “She talks French and Italian as well as English. She has often talked to me readily and well in Latin and moderately so in Greek. When she writes Greek and Latin nothing is more beautiful than her handwriting.”

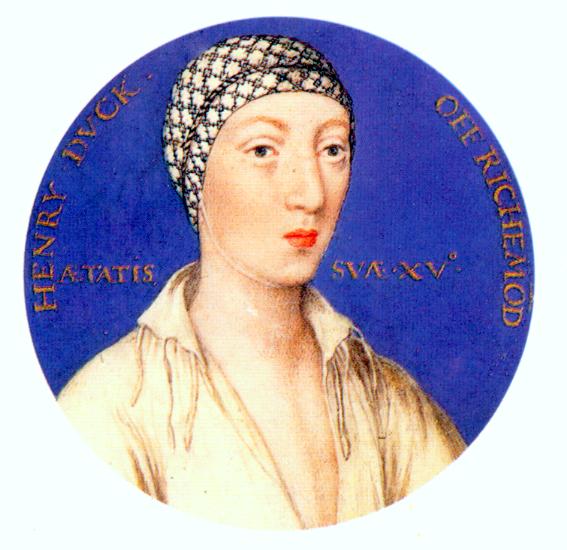

Elizabeth at the age of 13; Credit – Wikipedia

When Henry VIII died in 1547, Elizabeth was sent to live in the household of Henry’s widow Catherine Parr, who soon married Thomas Seymour, the uncle of Elizabeth’s half-brother King Edward VI. When Catherine Parr became pregnant, Seymour began to take an interest in the 14-year-old Elizabeth. Seymour had reputedly plotted to marry Elizabeth before marrying Catherine, and it was reported later that Catherine discovered the two in an embrace. According to the testimony of Kat Ashley, on a few occasions, before the situation risked getting completely out of hand, Catherine appears not only to have given her permission for the horseplay but also assisted her husband. Elizabeth was sent away in May 1548 to stay with Sir Anthony Denny’s household and never again saw her beloved stepmother, who died of childbed fever shortly after giving birth to a daughter.

After the early death of Henry VIII’s son and heir Edward VI at the age of fifteen in 1553, Lady Jane Grey followed him to the throne. As Edward VI lay dying, he was persuaded to name Lady Jane Grey as his successor to prevent his Catholic half-sister Mary from becoming queen. This also excluded his half-sister Elizabeth, the descendants of his aunt Margaret Tudor, and even Lady Jane’s own mother Frances Brandon, the daughter of his aunt Mary Tudor. Within nine days Mary asserted her rightful claim to the English throne. On August 3, 1553, as Queen Mary I rode triumphantly into London, her half-sister Elizabeth was at her side. Soon there was a rift between the sisters. Mary was a devout Catholic and Elizabeth leaned toward Protestantism.

In 1554, Elizabeth refused to participate in Sir Thomas Wyatt’s Rebellion which arose out of concern over Queen Mary I’s determination to marry Philip of Spain. Nevertheless, Elizabeth was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Elizabeth was moved from the Tower to Woodstock in Oxfordshire, where she was to spend almost a year under house arrest. She was then moved to Hatfield House in Hertfordshire, where she eventually received the news of the death of her half-sister Mary and her accession to the throne on November 17, 1558. Upon hearing the news, Elizabeth reportedly said, “This is the Lord’s doing and it is marvelous in our eyes.” Elizabeth’s coronation took place on January 15, 1559, at Westminster Abbey in London, England.

Elizabeth I in her coronation robes; Credit – Wikipedia

From the start of Elizabeth’s reign, she was expected to marry to provide for the succession. Although she received many offers, she never did marry and the reasons for this are unclear. She continued to consider suitors until she was about fifty. In October 1562, Elizabeth had smallpox and there was fear she would die. Elizabeth was the last surviving Tudor and was still unmarried and childless. After her recovery, the succession question became a heated debate in Parliament. Parliament urged the queen to marry or nominate an heir, and she refused to do either. Her last courtship (1579 – 1581) was with Francis, Duke of Anjou, who was 22 years younger.

Important People During Elizabeth I’s Reign

- Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester: nobleman, the favorite and close friend of Elizabeth I

- Sir Francis Walsingham: principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I, popularly remembered as her “spymaster”

- Sir Francis Drake: sea captain, privateer, navigator, slaver, and politician; second person to circumnavigate the world

- Sir Walter Raleigh: writer, poet, soldier, politician, courtier, spy, and explorer; popularized tobacco in England, granted Raleigh a royal charter, authorizing him to explore, colonize, and rule in the New World

- Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex: nobleman and a favorite of Elizabeth I, executed for leading an unsuccessful coup d’état

- William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley: statesman, chief advisor of Queen Elizabeth I, Secretary of State and Lord High Treasurer

- Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury: administrator and politician, Secretary of State, Chief Minister

- Sir Nicholas Throckmorton: English diplomat and politician

- Sir Christopher Hatton: politician, Lord Chancellor of England and a favorite of Elizabeth I

- Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Edmund Grindal, Archbishop of Canterbury

- John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury

Some Events of Elizabeth I’s Reign

- 1558: Act of Supremacy: re-established the Church of England’s independence from Rome, Elizabeth is given the title Supreme Governor of the Church of England

- 1559: Act of Uniformity: outlined what form the English Church should take, re-established the Book of Common Prayer

- 1568: Mary, Queen of Scots is imprisoned after losing her crown and fleeing to England

- 1570: Regnans in Excelsis: papal bull issued by Pope Pius V, declared Elizabeth to be a heretic, released all of her subjects from any allegiance to her, and excommunicated any who obeyed her orders

- 1577–1580: Sir Francis Drake sails around the world

- 1584: Virginia colony of Roanoke Island established by Sir Walter Raleigh

- 1585–1604: Anglo–Spanish War, an intermittent conflict between Spain and England

- 1586: England and Scotland signed the Treaty of Berwick, a peace and defensive agreement

- 1587: Mary, Queen of Scots is executed after her implication in the Babington Plot, a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, Queen Elizabeth signs the death warrant

- 1588: Spanish Armada is defeated, part of the Anglo-Spanish War

- 1594 – 1603: Nine Years’ War or Tyrone’s Rebellion between the forces of Gaelic Irish chieftains and their allies, against English rule in Ireland

- 1600: Queen Elizabeth I grants a charter to East India Company,

the beginning of the British Empire in India

Portrait of Elizabeth to commemorate the defeat of the Spanish Armada, depicted in the background. Elizabeth’s hand rests on the globe, symbolizing her international power; Credit – Wikipedia

Elizabeth was vain about her appearance and loved to dress in elaborate dresses, bedecked with many jewels. She refused to admit that she was aging and in later life, she wore a huge red wig and used many cosmetics. Mirrors in her palaces were removed so she did not have to look at her aging reflection.

Queen Elizabeth I, circa 1595; Credit – Wikipedia

In January 1603, while suffering from a cold, Elizabeth moved from Whitehall Palace to Richmond Palace. She recovered from the cold but fell ill at the end of February with severe tonsillitis. She had no appetite and suffered from insomnia. On March 18, 1603, she became very ill and refused to go to bed, instead lying on a heap of pillows piled on the floor. When Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury urged her to go to bed, Elizabeth showed a last flash of her feisty spirit and said to him, “Little man, little man, MUST is not a word to use to princes.”

The Death of Elizabeth I, Queen of England by Paul Delaroche, 1828; Credit – Wikipedia

Since none of the children of Henry VIII had children, King James VI of Scotland, the only child of Mary, Queen of Scots, was the senior heir of King Henry VII through his eldest daughter Margaret Tudor. From 1601 onward, Sir Robert Cecil, Queen Elizabeth’s chief minister, maintained a secret correspondence with James to facilitate a smooth succession. On her deathbed, Queen Elizabeth finally gave assent for James to succeed her. Queen Elizabeth I died on March 24, 1603, at the age of 69. A messenger was sent at once to Scotland to bring James the news of his accession to the English throne as King James I of England. Elizabeth was buried at Westminster Abbey in the same vault as her half-sister Queen Mary I. The tomb erected above only has Elizabeth’s effigy, but King James I ordered this to be inscribed upon the tomb in Latin: Regno consortes et urna, Hic obdorminus Elizabetha et Maria sonores in spe resurrectionis – Partners both in throne and grave, here we rest as sisters, in hope of our resurrection.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Tudor Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Index

- House of Tudor Index

- British Royal Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Other Important Events

- Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present)

- First Cousins of Queen Elizabeth I

- History and Traditions: Tudor Weddings

- House of Tudor Burial Sites

- House of Tudor Christenings