by Emily McMahon and Susan Flantzer, Revised May 2020

© Unofficial Royalty 2013

Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, aged 19, married 24-year-old Prince Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine, the future Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine on July 1, 1862, at Osborne House in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, England. The couple had seven children and the British Royal Family, the line of King Charles III, descends from this marriage as his father, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was a great-grandson of Alice and Ludwig.

Alice’s Early Life

Princess Alice painted in 1861 by Franz Xaver Winterhalter; Credit – Wikipedia

Alice was the third child and second daughter of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and her husband Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Alice’s upbringing was typical for the times, spending most of her time with her siblings under the watch of nannies and tutors. From an early age, Alice developed a deep sense of compassion for others that would continue to develop in her adult years.

In March 1861, Alice’s maternal grandmother, the Duchess of Kent, died. Alice had been with her grandmother during her final days and had established herself as the “family caregiver”. After the Duchess of Kent died, it was Alice who Prince Albert sent to take care of Queen Victoria, whose intense grief over the Duchess’ death was unbearable. Queen Victoria later attributed Alice’s efforts with helping her to get through the dark days that followed. Sadly, it would not be long until Alice’s caregiving skills would be needed again.

At the end of 1861, Alice’s father, Prince Albert, fell ill with typhoid. Alice stayed at his side, nursing him through the last days of his life. Albert died on December 14, 1861, and Queen Victoria went into seclusion. It was Princess Alice who then stepped in as unofficial secretary to her mother, assisted by her younger sister Louise, handling all of the state papers and correspondence, all while trying to support and comfort her mother.

Ludwig’s Early Life

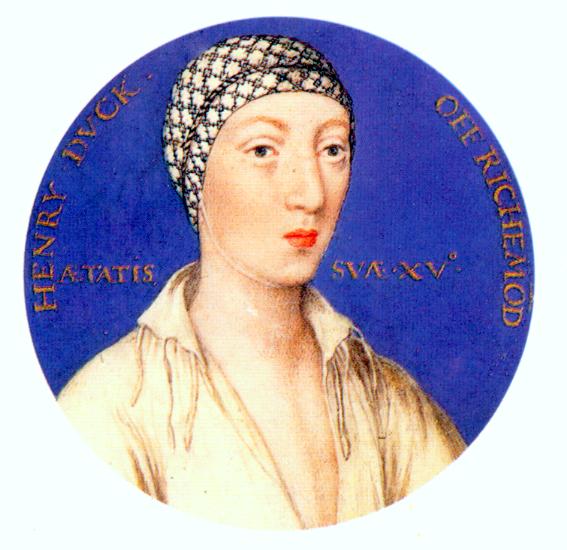

Prince Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine in 1860; Credit – Wikipedia

Ludwig was the eldest of the four children of Prince Karl of Hesse and by Rhine (a son of Grand Duke Ludwig II and younger brother of Grand Duke Ludwig III) and his wife Princess Elisabeth of Prussia (a granddaughter of King Friedrich Wilhelm II). After it became evident that Grand Duke Ludwig III of Hesse and by Rhine would have no children with his wife Mathilde of Bavaria, his nephew Ludwig was groomed as his successor.

Ludwig began his military training in 1854, along with his younger brother Heinrich, and the two later studied at the University of Göttingen and the University of Giessen. From an early age, Ludwig was destined for a military career. After his marriage to Alice, he would go on to lead the Hessian forces in both the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.

At the time of the wedding, Queen Victoria issued Letters Patent giving Ludwig the style Royal Highness. This would only be valid in the United Kingdom. Elsewhere, he was still a Grand Ducal Highness. Four days after the wedding, Ludwig was created a Knight of the Order of the Garter.

The Engagement

Alice and Ludwig in December 1860, after their engagement; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1858, Alice’s eldest sibling Victoria, Princess Royal (Vicky) married Prince Friedrich of Prussia, the future Friedrich III, German Emperor and King of Prussia, and Queen Victoria and Prince Albert had hoped to make an equally impressive marriage for Alice. A visit from Willem, Prince of Orange (son and heir of King Willem III of the Netherlands who predeceased his father), had failed to make a positive impression on Alice or her parents. Vicky had met Prince Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine in the early months of her marriage and suggested that he may be suitable for Alice. Ludwig and his brother Heinrich were invited to Windsor in 1860 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to look him over. Alice and Ludwig quickly developed a connection and on a second visit in December 1860, the couple became engaged. Following Queen Victoria’s formal consent, the engagement was announced on April 30, 1861. The Queen negotiated with Prime Minister Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston to get Parliament to approve a dowry of £30,000.

The Wedding Site

Osborne House; Credit – By Humac45 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35090565

Unfortunately for Alice and Ludwig, the deaths in 1861 of Alice’s maternal grandmother and father affected their wedding plans. The 1858 wedding of Victoria, Princess Royal at the Chapel Royal of St. James’s Palace in London had been a grand showcase but Alice’s wedding was a muted and sad private ceremony meant for family only. A spring wedding was out of the question but Queen Victoria declared that the wedding must be held sooner rather than later as Prince Albert had wished. A private wedding with far fewer guests than the weddings of Alice’s siblings was scheduled for July 1, 1862, at Osborne House in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, England.

Victoria and Albert, whose primary residences were Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, felt they needed residences of their very own. They purchased Osborne House in 1845 but they soon realized that the house was too small for their growing family. They decided to replace the house with a new, larger residence. The new Osborne House was built between 1845 and 1851. Albert’s architectural talents are evident in the seaside Italian-style palace. Osborne House and Balmoral Castle in Scotland, which Albert also helped to design, became their favorite homes.

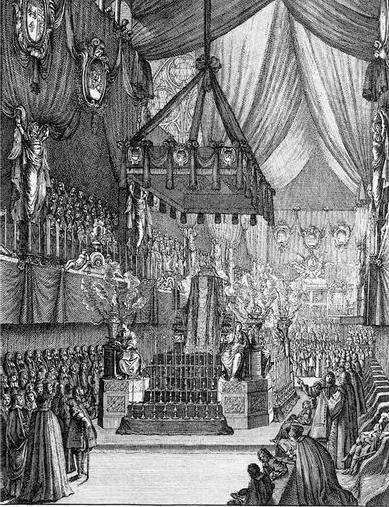

The Dining Room at Osborne House with the large painting of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their five eldest children by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, was converted into a temporary chapel for the wedding ceremony. Also, above the door was a Winterhalter painting of Queen Victoria’s mother. Below is a painting of the wedding The Marriage of Princess Alice, 1st July 1862 by George Housman Thomas.

The Marriage of Princess Alice, 1st July 1862 by George Housman Thomas; Credit – Royal Collection Trust

Information about the above painting from Royal Collection Trust: The Marriage of Princess Alice, 1st July 1862: The marriage of Princess Alice, the third child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and Prince Louis of Hesse took place ‘in the strictest privacy’ barely six months after the death of Prince Albert. The ceremony was held in the Dining Room at Osborne ‘which was very prettily decorated, the altar being placed under our large family picture’ (RCIN 405413), as the Queen recorded in her Journal. A portrait of Victoria, Duchess of Kent, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (RCIN 405129) also hangs on the back wall in this painting.

Wedding Guests

Royal Guests – The Bride’s Family

- Queen Victoria, mother of the bride

- The Prince of Wales, brother of the bride

- Prince Alfred, brother of the bride

- Prince Arthur, brother of the bride

- Prince Leopold, brother of the bride

- Princess Helena, sister of the bride

- Princess Louise, sister of the bride

- Princess Beatrice, sister of the bride

- The Duchess of Cambridge (Augusta of Hesse-Kassel), great-aunt of the bride

- The Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Augusta of Cambridge), first cousin once removed of the bride

- Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge, first cousin once removed of the bride

- Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, first cousin once removed of the bride

- Crown Prince Friedrich of Prussia, brother-in-law of the bride (Crown Princess Victoria, Alice’s sister was eight months pregnant with her third child and was unable to travel)

- Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, paternal uncle of the bride

- Prince August of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, first cousin once removed of the bride

- Princess August of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Clémentine of Orléans), wife of Prince August

- Princess Feodora of Leiningen, Princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, Queen Victoria’s half-sister, maternal half-aunt of the bride

- The Count Gleichen (Prince Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the son of Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora who made a morganatic marriage), half-first-cousin of the bride

Royal Guests – The Groom’s Family

- Prince Karl of Hesse and by Rhine, groom’s father

- Princess Karl of Hesse and by Rhine (Elisabeth of Prussia), groom’s mother

- Prince Heinrich of Hesse and by Rhine, brother of the groom

- Prince Wilhelm of Hesse and by Rhine, brother of the groom

- Princess Anna of Hesse and by Rhine, sister of the groom

Other Royal Guests

- Prince Louis of Orleans, Duke of Nemours

- Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar

- Maharajah Duleep Singh

Other Guests

Among the other guests, were several representatives of the British Government and friends of the royal family.

- Count von Goertz, Minister of the Grand Ducal Court of Hesse and by Rhine accredited to Great Britain

- Charles Longley, Archbishop of York

- Richard Bethell, 1st Baron Westbury, Lord Chancellor

- Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville, Lord President of the Council

- John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, First Lord of the Treasury

- Sir George Grey, Baronet, Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Jean-Sylvain Van De Weyer, Belgian Minister accredited to Great Britain, representing Leopold I, King of the Belgians, uncle to both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and the bride’s great-uncle

- James Hamilton, 2nd Marquess of Abercorn

- Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

- George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon

- George Byng, 7th Viscount Torrington

- Lord George Lennox, Gentleman of the Bedchamber to Prince Albert

- Lord Alfred Paget, Chief Equerry to Queen Victoria

- Lieutenant-General The Honourable Charles Grey and The Honourable Mrs. Charles

Grey, Private Secretary to Queen Victoria and his wife

- Major-General William Wylde

- Colonel The Honorable Alexander Gordon

- Colonel Francis Seymour

- The Reverend W. Jolly

- Dr. Becker, Prince Albert’s librarian

Her Majesty’s Household

- Mistress of the Robes – Elizabeth Wellesley, Duchess of Wellington

- Lady-in-Waiting – Anne Murray, Duchess of Atholl

- The Lady Superintendent – Lady Caroline Barrington

- Maids of Honor in Waiting – The Honorable Beatrice Byng, The Honorable Emily Cathcart

- The Lord Steward – Edward Eliot, 3rd Earl of St. Germans

- The Lord Chamberlain – John Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney

- The Master of the Horse – George Brudenell-Bruce, 2nd Marquis of Ailesbury

- The Vice-Chamberlain – Valentine Augustus Browne, 4th Viscount Castlerosse

- The Keeper of the Privy Purse – Colonel The Honourable Sir Charles Beaumont Phipps

- The Honourable Lady Phipps and The Honourable Miss Harriet Phipps (Maid of Honour in Ordinary to Queen Victoria, later served as a Woman of the Bedchamber from 1889 until Victoria’s death) – wife and daughter of Sir Charles Beaumont Phipps

- The Dean of Windsor and Resident Chaplain to The Queen – The Honourable and Very Reverend Gerald Wellesley and his wife The Honourable Mrs. Wellesley

- The Master of the Household – Colonel Thomas Biddulph and his wife The Honourable Mrs. Biddulph

- The Equerries in Waiting – Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Charles Fitzroy, Lieutenant-Colonel The Honourable Dudley de Ros

- Physicians in Ordinary – Sir James Clark, Baronet

- Librarian to The Queen – Mr. Bernard Woodward

- German Librarian to The Queen – Mr. Carl Ruland

- The Rector of Whippingham Church, Isle of Wight – Reverend G. Prothero

- Equerry to The Prince of Wales – Captain Gray

- Major Cowell – Major John Cowell

- Governor to Prince Arthur and Prince Leopold – Major Howard Elphinstone

- Lady-in-Waiting to The Duchess of Cambridge – Lady Geraldine Somerset

- Gentleman-in-Waiting to The Duchess of Cambridge – Lieutenant.Colonel Home Purves

- Equerry-in-Waiting to The Duke of Cambridge – Colonel Tyrwhitt

- Lady in Waiting to The Queen in Attendance on Princess Alice – Jane Spencer, Baroness Churchill

- Ladies in Waiting to Princess Alice – Baroness Von Schenck zu Schweinsberg, Baroness Von Grancy

- Equerry to the Queen in Attendance on Princess Alice – Major-General Francis Seymour

Foreign Royalty Attendants

- Gentleman-in-Waiting to Prince Ludwig of Hesse and by Rhine – Captain Westerweller

- Equerry to the Queen in Attendance on Prince and Princess Karl of Hesse and by Rhine – Lieutenant-Colonel du Plat

- Lady-in-Waiting to Princess Karl of Hesse and by Rhine – Baroness von Schaeffer-Bernstein

- Lady-in-Waiting to Princess Anna of Hesse and by Rhine – Baroness von Roeder

- Gentlemen in Waiting to Prince Karl of Hesse and by Rhine – Baron Von Ricou and Major Von Grolman

Bridesmaids and Supporters

Ludwig was supported by his 24-year-old brother Prince Heinrich of Hesse and by Rhine. Prince Albert’s elder brother Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, gave the bride away.

The bridesmaids were:

- Princess Helena of the United Kingdom, Alice’s 16-year-old sister

- Princess Louise of the United Kingdom, Alice’s 14-year-old sister

- Princess Beatrice of the United Kingdom, Alice’s 5-year-old sister

- Princess Anna of Hesse and by Rhine, Ludwig’s 19-year-old sister

The Wedding Attire

Princess Alice in her wedding dress; Credit – Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/2905616/princess-alice-in-her-wedding-dress

Although Alice and her mother took some joy in arranging her trousseau, all the outfits were black due to the required mourning. On the morning of the wedding, Alice’s sisters wore their black mourning dresses. They changed into their white bridesmaid’s dresses right before the wedding ceremony and changed back into their mourning dresses after the newlyweds left for their honeymoon.

Alice wore a dress with a deep flounce of Honiton lace and a border of orange blossoms at the bottom of the dress. The veil of Honiton lace was held in place by a wreath of orange blossoms and myrtle. The dress was a simple style and did not have a court train. The bridesmaids wore similar white dresses with violet trim as depicted in the wedding painting above.

The guests were required to wear mourning dress: the men in black evening coats, white waistcoats, grey trousers, and black neckcloths; the ladies in grey or violet mourning dresses, and grey or white gloves.

The Wedding Ceremony

Embed from Getty Images

The wedding service was conducted by Charles Longley, Archbishop of York in the “unavoidable absence” of the bedridden John Bird Sumner, Archbishop of Canterbury who died two months later and was succeeded by Longley. A local decorator had erected an altar in the Dining Room of Osborne House, covered in purple, velvet, and gold and surrounded by a gilt railing. No other decorating arrangements had been made.

At 1:00 PM, Queen Victoria accompanied by her four sons, The Prince of Wales, Prince Alfred, Prince Arthur, and Prince Leopold, and attended by Elizabeth Wellesley, Duchess of Wellington, Mistress of the Robes, and Anne Murray, Duchess of Atholl, Lady-in-Waiting were conducted from Queen Victoria’s apartments by the Lord Chamberlain, John Townshend, 1st Earl Sydney, to an armchair on the left side of the altar.

Next, the royal guests and the other guests were conducted to their places by the Lord

Chamberlain and the Vice-Chamberlain, Valentine Browne, 4th Earl of Kenmare. The parents of the bridegroom, Prince and Princess Karl of Hesse and by Rhine, and their youngest child Prince Wilhelm were placed on the left side of the altar. The Lord Chamberlain then conducted Ludwig, supported by his brother Prince Heinrich, to his place on the right side of the altar. Finally, the Lord Chamberlain proceeded to Queen Victoria’s apartments and conducted Alice to her place on the left side of the altar. Alice was supported by her uncle Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and was accompanied by her four bridesmaids, her sisters Princesses Helena, Louise, and Beatrice, and Ludwig’s sister Princess Anna. Once Alice was in her place, the wedding service began.

Queen Victoria sat in the armchair surrounded by her four sons, trying to maintain her composure. She spent the ceremony staring at the portrait of Prince Albert with his family hanging above the bride and groom. Queen Victoria would later describe the service to her daughter Vicky as “more of a funeral than a wedding.” Other guests similarly described the wedding as being a very sad occasion. Alice’s brothers cried throughout the service, as did the Archbishop of York. The death of Mathilde of Bavaria, the wife of Ludwig’s uncle Grand Duke Ludwig III of Hesse and by Rhine, a few weeks before the wedding, did nothing to raise the spirits of the wedding guests.

At the conclusion of the wedding ceremony, Alice and Ludwig were conducted by the Lord

Chamberlain to the nearby Horn Room. The guests were conducted to the Council Room where they had luncheon. Queen Victoria remained seated in her armchair until everyone had left, and then, with Princess Beatrice, also was conducted to the Horn Room, where they had luncheon with the newlywed couple.

The Honeymoon, Leaving England, Arriving in the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine

Embed from Getty Images

St. Clare Castle where Alice and Ludwig spent their honeymoon. In 1960, it was demolished after a fire.

At about 5:00 PM, Alice and Ludwig left Osborne House to travel to Ryde, a seaside town on the northeast coast of the Isle of Wight where they stayed at St. Clare Castle which belonged to Colonel Francis Vernon-Harcourt. Accompanying the newlyweds were Jane Spencer, Baroness Churchill (a Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Victoria from 1854 until 1900, the longest-serving member of Queen Victoria’s household), Major-General Francis Seymour (Prince Albert’s Groom in Waiting from 1840 until 1861), and Captain von Wenterweller (a courtier from the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine).

The day after the wedding, Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter Vicky, “A dagger is plunged in my bleeding, desolate heart when I hear from Alice this morning that she is proud and happy to be Louis’ wife.” Queen Victoria visited Alice and Ludwig twice during their stay at St. Clare Castle.

On July 9, 1862, Alice and Ludwig left England on the royal yacht Victoria and Albert for continental Europe on the way to their final destination, Darmstadt in the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine, now in the German state of Hesse. They visited Brussels, Belgium where they briefly stayed with Leopold I, King of the Belgians, born a Prince of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, the uncle of both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Alice and Ludwig arrived at the border of the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine on July 12, 1862. A train then took them to Mainz, then part of the Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine, where the first official reception took place. Alice and Ludwig crossed the Rhine River in a gaily decorated steamship. At the stop before Darmstadt, the capital of the Grand Duchy, Grand Duke Ludwig III and other members of the Hesse family boarded the steamship and accompanied the newlyweds to Darmstadt. At 4:30 PM on July 12, 1862, Alice and Ludwig made their state entry into Darmstadt. The streets were decorated with arches, flags, and flowers, the church bells were ringing and the assembled crowds enthusiastically cheered Alice and Ludwig.

Children

Alice, Ludwig, and their children, May 1875. Photo: The Royal Collection Trust

- Princess Victoria, Marchioness of Milford Haven (1863-1950), married Prince Louis of Battenberg (later Louis Mountbatten, Marquess of Milford Haven), had two sons and two daughters including Alice, the mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Louise who was the second wife of King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden (no children), and Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma

- Princess Elisabeth – “Ella” – Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia (1864-1919), married Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, no children

- Princess Irene (1866-1953), a hemophilia carrier, married Prince Heinrich of Prussia, had three sons

- Prince Ernst Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse (1868-1937), married (1) Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, had one daughter (2) Princess Eleonore of Solms-Hohensolms-Lich, had two sons

- Prince Friedrich – “Frittie” (1870-1873), died from a fall exacerbated by his hemophilia

- Princess Alix, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia (1872-1918), a hemophilia carrier, married Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia, had four daughters and one son

- Princess Marie – “May” (1874-1878), died from diphtheria a few weeks before her mother also died from diphtheria

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- 1884. Alice Grand Duchess Of Hesse, Princess Of Great Britain And Ireland – Biographical Sketch And Letters. London: John Murray.

- Mehl, Scott, 2015. Ludwig IV, Grand Duke Of Hesse And By Rhine. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/ludwig-iv-grand-duke-of-hesse-and-by-rhine/> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- Mehl, Scott, 2015. Princess Alice Of The United Kingdom, Grand Duchess Of Hesse And By Rhine. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/princess-alice-of-the-united-kingdom-grand-duchess-of-hesse-and-by-rhine/> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- Packard, Jerrold., 2013. Victoria’s Daughters. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Rct.uk. 2020. George Housman Thomas (1824-68) – The Marriage Of Princess Alice, 1St July 1862. [online] Available at: <https://www.rct.uk/collection/404479/the-marriage-of-princess-alice-1st-july-1862> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- The Gazette. 1862. Page 3429 | Issue 22641, 7 July 1862 | London Gazette /CEREMONIAL Observed At The Marriage Of HER ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS ALICE-MAUD-MARY,. [online] Available at: <https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/22641/page/3429> [Accessed 18 May 2020].

- The Royal Family. 2020. Royal Wedding Dresses Throughout History. [online] Available at: <https://www.royal.uk/wedding-dresses> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- Trove. 1862. THE MARRIAGE OF THE PRINCESS ALICE. – The Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864) – 25 Sep 1862. [online] Available at: <https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4608199> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- Van der Kiste, John, 2011. Queen Victoria’s Children. Stroud: The History Press.