by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

Johanniterkirche; Credit Wikipedia by Von Matthias Süßen

History

Originally a Roman Catholic church of The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, also known as the Knights Hospitaller, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, Johanniterkirche (Saint John’s Church) is an Evangelical Lutheran church in Mirow, on the Mirow Castle Island in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. From 1704, Johanniterkirche was the court church and burial place of the Dukes and Grand Dukes of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Only the three-bay choir from the 14th century has been preserved from the original church. The wider nave was built around the time when the Dukes of Mecklenburg-Strelitz took possession of the church.

On September 4, 1742, lightning struck the church’s wooden tower, and the church burned down. The tower and the church’s furnishings were destroyed. During the reign of Adolf Friedrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg (reigned 1708 – 1752), the church was restored in the Baroque style. A large baroque tower was built, and the interior of the church was restored with baroque furnishings. The church was reconsecrated in 1744. The altarpiece was created in 1750 by court painter Charles Maucourt. (link in German). In 1868, the altarpiece was replaced by a copy of Christ on the Cross painted by Marie of Hesse-Kassel, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1796 – 1880), wife of Grand Duke Georg of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, after a painting by the German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer.

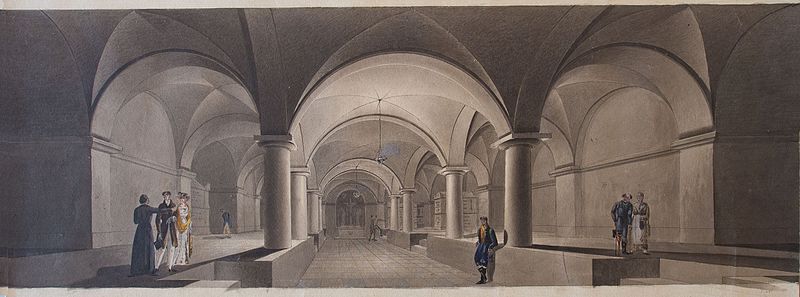

Interior before 1945; Credit – Wikipedia

On April 30, 1945, during World War II, the Johanniterkirche was destroyed by German Wehrmacht bombing. Only the outer walls and the princely crypt survived the bombing. Architect Paul Zühlke oversaw the restoration. His plans included the reconstruction of the building and plans for the altar, the pulpit, the baptismal font, and the central windows with the symbols of faith (a cross), hope (an anchor), and charity (a heart). On September 3, 1950, the Johanniterkirche was reconsecrated.

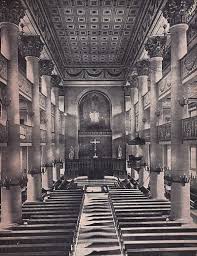

Interior of the Johanniterkirche in 2024; Credit – Wikipedia by Von Matthias Süßen

Burials

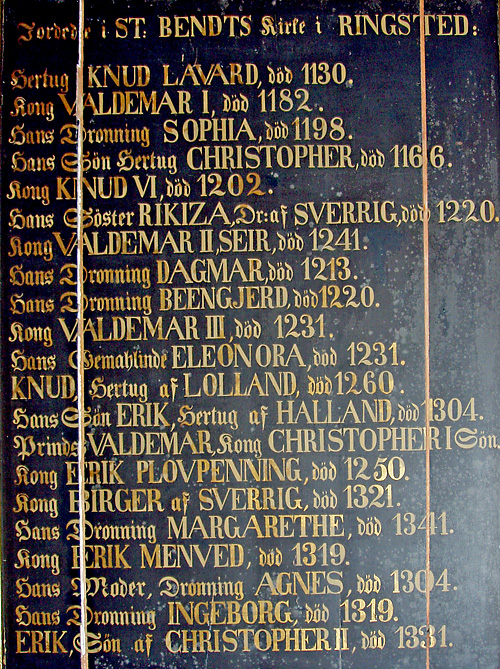

The crypt of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz; Credit – Wikipedia by Von Matthias

After the death of Johanna of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1680 – 1704), second wife of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, an older crypt was rededicated and expanded as the princely crypt and burial site of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The crypt was expanded several times, and the reigning dukes, their wives, and their closest members of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz were interred in the crypt.

In 1921, 52 coffins in four crypt rooms were documented. After the 1945 bombing of the church, many coffins were damaged and had been looted. In the publicly accessible part of the crypt, there are now 22 coffins, including those of five of the eight rulers of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. In 2015, the German federal government, the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern state government, and the Mirow local government pledged a combined amount of around 900,000 euros for the renovation of the princely crypt, which was completed in 2018.

Adolf Friedrich VI, the last Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, died by suicide on February 23, 1918, and was buried on Love Island, a small island off Castle Island, the site of the Grand Ducal Palace and the Johanniterkirche.

Members of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz who were buried at the Johanniterkirche

- Karl of Mecklenburg (1626 – 1670), son of Adolf Friedrich I, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Johann Georg of Mecklenburg (1629 – 1675), son of Adolf Friedrich I, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Johanna of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1680 – 1704), second wife of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1658 – 1708)

- Sophie Christiane Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1706 – 1708), daughter of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Magdalene Christine Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1711 -1713), daughter of Adolf Friedrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Maria Sophie of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1710 -1728), daughter of Adolf Friedrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Caroline of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1736), daughter of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and granddaughter of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Elisabeth Christine of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1739 – 1741), daughter of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and granddaughter of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Sophie Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1740 – 1742), daughter of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and granddaughter of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Gotthelf of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1745), son of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Christiane Emilie of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (1681 – 1751), third wife of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Adolf Friedrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1686 – 1752)

- Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1708 – 1752), son of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Elisabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen (1713 – 1761), wife of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Dorothea Sophie of Holstein-Sonderburg-Plön, Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1692 – 1765), wife of Adolf Friedrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg

- Caroline Auguste of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1771 – 1773), daughter of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1794 – 1815), Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1815 – 1816)

- Georg Karl Friedrich of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1772 – 1773), son of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1794 – 1815), Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1815 – 1816)

- Friedrich Georg Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1774), son of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (from 1794 to 1815), Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (from 1815 to 1816)

- Friederike of Hesse-Darmstadt, Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1752 -1782), first wife of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Grand Duke after her death), sister of Charlotte of Hesse-Darmstadt, Carl II’s second wife; Friederike died from complications delivering Augusta Albertine, below, who lived only one day. Her sister Charlotte also died in childbirth.

- Augusta Albertine of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1782), daughter of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Friedrich Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1781 – 1783), son of Carl II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Georg August of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1748 – 1785), son of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, grandson of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Charlotte of Hesse-Darmstadt, Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1755 – 1785), second wife of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Grand Duke after her death), sister of Friederike of Hesse-Darmstadt, Carl II’s first wife; both sisters died in childbirth

- Christiane of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1735 – 1794), daughter of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and granddaughter of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Adolf Friedrich IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1738 – 1794)

- Ernst Gottlob Albert of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1742 – 1814), son of Karl of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and grandson of Adolf Friedrich II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Carl II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1741 – 1816)

- Maria Luise Albertine of Leiningen-Dagsburg-Falkenburg, Princess of Hesse-Darmstadt (1729 – 1818), wife of Prince George William of Hesse-Darmstadt, mother of Friederike and Charlotte, the first and second wives of Carl II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (later Grand Duke). After her daughters died in childbirth, Maria Luise took over the care and education of her grandchildren.

- Georg Karl of Hesse-Darmstadt (1754 – 1830), brother of Friederike of Hesse-Darmstadt and Charlotte of Hesse-Darmstadt

- Karl of Mecklenburg (1785 – 1837), son of Carl II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1818 – 1842), daughter of Georg, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Friedrich Wilhelm of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1845), son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Nikolaus of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1854), son of Georg August of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and grandson of George, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Georg, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1779 – 1860)

- Marie of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1861), daughter of Georg August of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and granddaughter of George, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Caroline of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Crown Princess of Denmark (1821 – 1876), daughter of Georg, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, 2nd wife of the future Frederik VII, King of Denmark (divorced)

- Marie of Hesse-Kassel, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1796 – 1880), wife of Grand Duke Georg of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Friedrich Wilhelm, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1819 – 1904)

- Karl Borwin of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1888 – 1908), killed in a duel, son of Adolf Friedrich V, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Adolf Friedrich V, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1848 – 1914)

- Augusta of Cambridge, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1822 – 1916), wife of Friedrich Wilhelm, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and granddaughter of King George III of the United Kingdom

- Elisabeth of Anhalt, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1857 – 1933), wife of Adolf Friedrich V, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Georg Alexander of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1921 – 1996), Head of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz from 1963 until his death

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Aus der Geschichte von 1226 bis 1950 – Johanniterkirche zu Mirow. (2025). Johanniterkirche-Mirow.de. https://www.johanniterkirche-mirow.de/kirche/geschichte/

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2014, July 18). denkmalgeschütztes Kirchengebäude auf der Schlossinsel in Mirow in Mecklenburg. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johanniterkirche_Mirow

- Johanniterkirche in Mirow in Mirow, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern – Find a Grave Cemetery. (2021). Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2301129/johanniterkirche-in-mirow

- Johanniterkirche zu Mirow. (2025). Johanniterkirche-Mirow.de. https://www.johanniterkirche-mirow.de/

- Kirchgemeinde – Johanniterkirche zu Mirow. (2025). Johanniterkirche-Mirow.de. https://www.johanniterkirche-mirow.de/kirchenseiten/kirchgemeinde/

- Mecklenburgische Seenplatte. (2025). Johanniterkirche Zu Mirow. https://www.mecklenburgische-seenplatte.de/reiseziele/johanniterkirche-mirow