by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2025

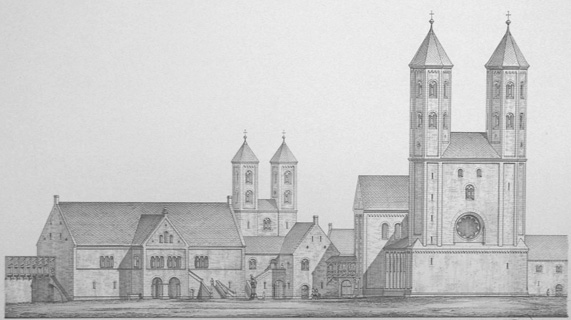

St. Michael’s Church in Pforzheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany; Credit – Wikipedia

History

Originally a Roman Catholic church dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel, and then a Lutheran church after the Protestant Reformation, Saint Michael‘s Church, located in Pforzheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, is currently a member of the Evangelical Church in Germany, a federation of twenty Lutheran, Reformed, and United Protestant regional Churches in Germany. Saint Michael’s Church is owned by the state of Baden-Württemberg, and is rented to the Evangelical Church in Pforzheim.

From 1538, Saint Michael’s Church was designated as the burial place of the Ernestine line of the House of Baden. Until 1860, almost all members of that branch of the House of Baden were buried at St. Michael’s Church. In 1556, Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach introduced the Protestant Reformation in the Margraviate of Baden, and Saint Michael’s Church became a Lutheran church.

In 1220, Herman V, Margrave of Baden chose Pforzheim as his residence. Five years later, a castle was built that became the residence of the Margraves of Baden and their descendants. Because Saint Michael’s Church was so close to the castle, it was often called Schlosskirche (Castle Church).

Saint Michael’s Church and the archive tower of the castle built by Herman V, Margrave of Baden are the last surviving medieval structures in Pforzheim. Pforzheim’s other medieval structures were destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648), the Nine Years’ War (1688 – 1697), and most recently in World War II (1939 – 1945).

In 1535, the Margraviate of Baden was split into the Margraviate of Baden-Durlach and the Margraviate of Baden-Baden. In 1565, Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach chose Durlach as his new residential town. However, Pforzheim remained one of the administrative centers. In 1738, ten-year-old Karl Friedrich succeeded as Margrave of Baden-Durlach upon his grandfather’s death. Baden-Durlach was one of the branches of the Margraviate of Baden, which had been divided several times over the previous 500 years. When August Georg, Margrave of Baden-Baden, died in 1771 without heirs, his territory was inherited by Karl Friedrich. This brought all of the Baden territories together once again, and Karl Friedrich became Margrave of Baden. Upon the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Karl Friedrich declared himself sovereign, as Grand Duke, of the newly created Grand Duchy of Baden. In 1918, after Germany’s defeat in World War I, all the constituent monarchies in the German Empire, including the Grand Duchy of Baden, were abolished. The land encompassing the Grand Duchy of Baden is now in the German state of Baden-Württemberg.

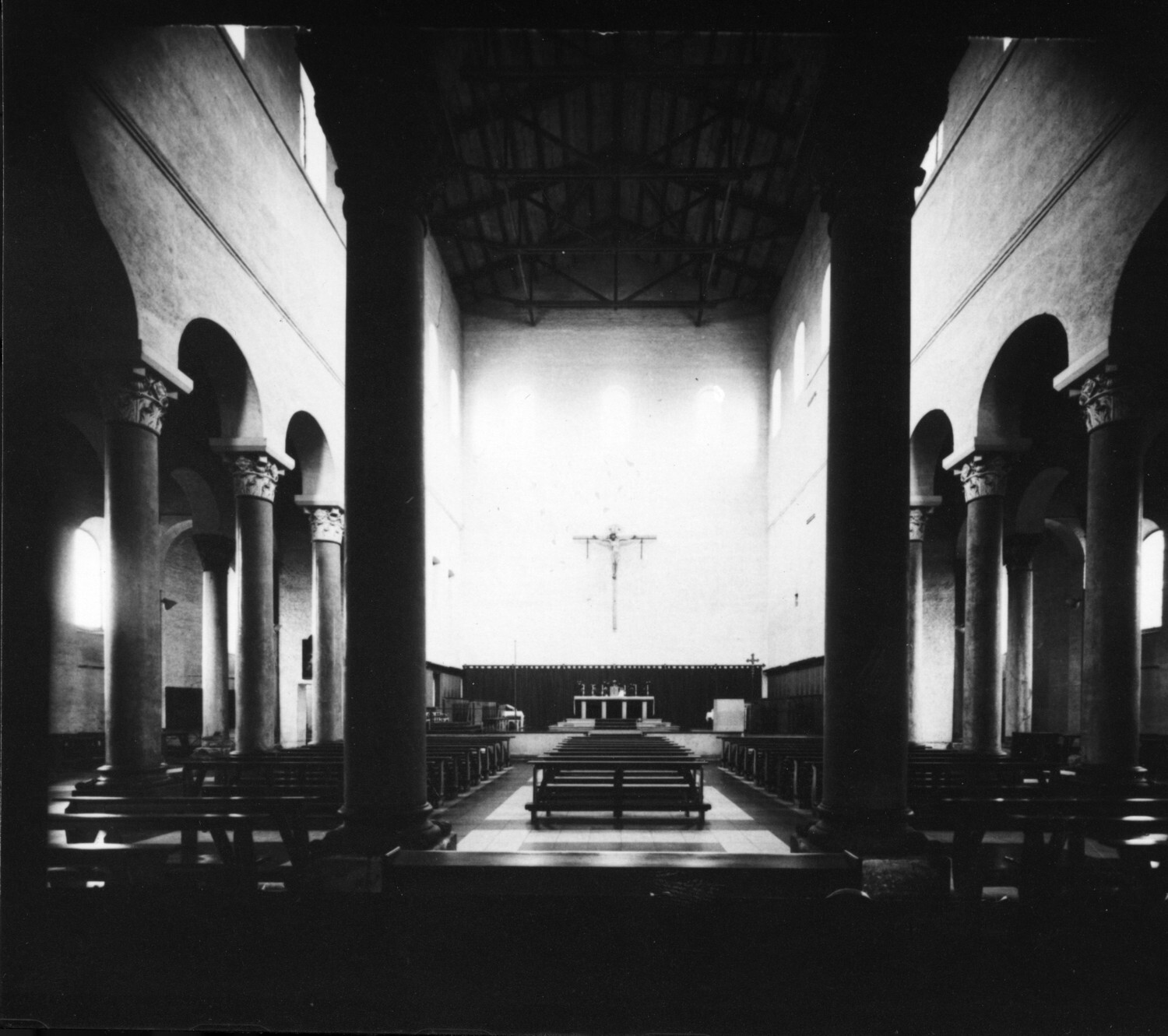

Interior of St. Michael’s Church; Credit – Von SchiDD – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42939836

Saint Michael’s Church was built on the site of a Romanesque church between 1225 and 1475 in the Romanesque and late Gothic style. The first nave was completed around 1270. The choir and Saint Margaret’s Chapel were built between 1290 and 1310. Around 1470, Pforzheim stonemason Hans Spryss von Zaberfeld built a late Gothic choir at the eastern end and a rood screen between the choir and the nave. The church was damaged during the Nine Years’ War (1688 – 1697), but extensive restoration work was not carried out until the 19th century.

Hans Spryss von Zaberfeld’s rood screen; Credit – Von Moleskine – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76589652

*********************

World War II Destruction

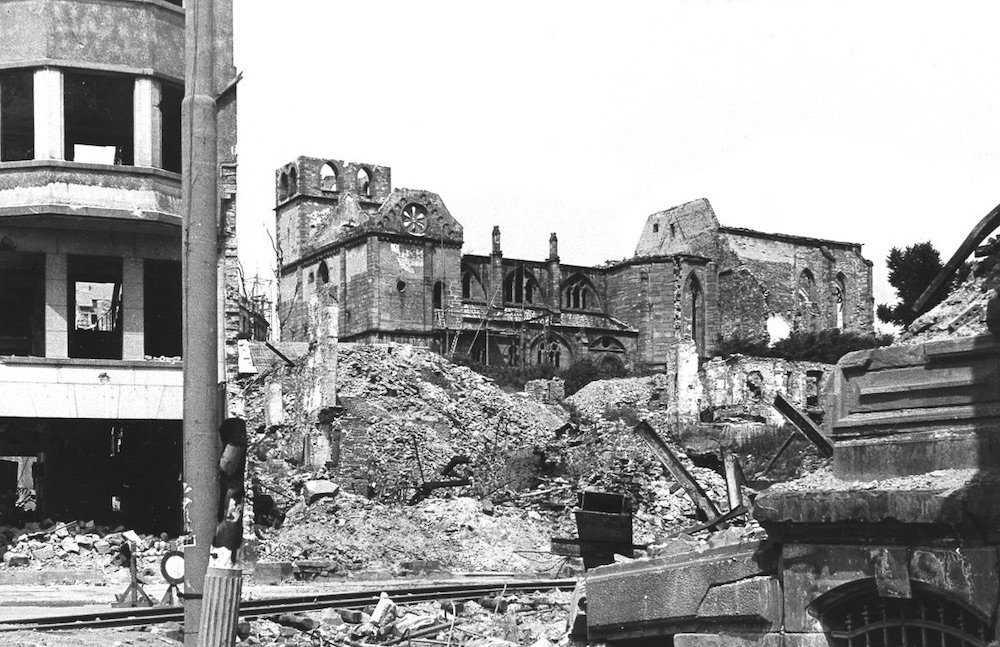

The Pforzheim in 1946; Credit – Wikipedia

On February 23, 1945, Pforzheim was nearly totally destroyed in an air raid by 379 British bombers within 22 minutes. At least 17,600 people, a third of the population, were killed. St. Michael’s Church avoided destruction, but the bombing caused severe damage.

Pforzheim before the bombing. St. Michael’s Church can be seen in the upper right. Credit – https://www.foerderverein-schlosskirche.de/schlosskirche

The damage to St. Michael’s Church from World War II bombing; Credit – https://www.foerderverein-schlosskirche.de/schlosskirche

*********************

Restoration

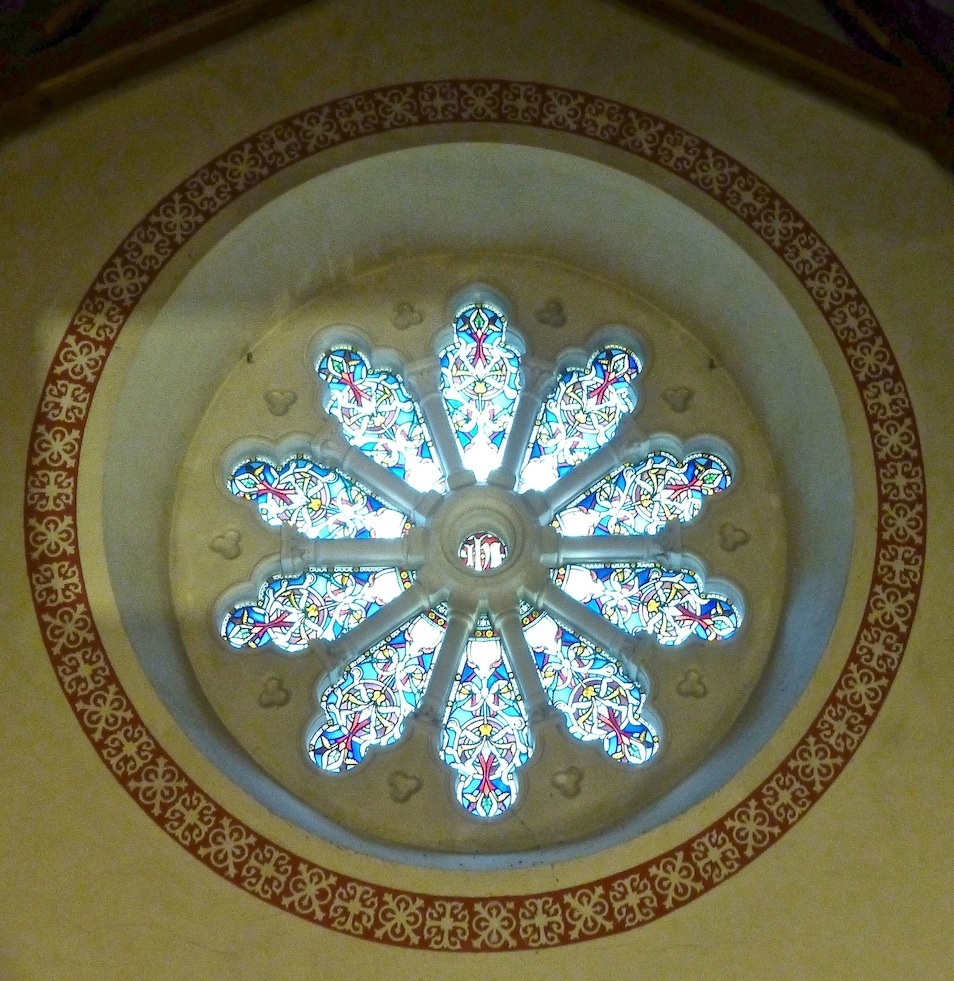

The State Building Authority supervised the restoration of Saint Michael’s Church after World War II with the support of the Friends of the Castle Church Foundation. German sculptor Oskar Loos (1903 – 1990) recreated the sculptures. The stained-glass windows in the choir were created by German painter and stained glass artist Charles Crodel, in collaboration with German architect Hermann Hampe (link in German).

The church’s portal, covered with bronze plates, was created in 1959 by German sculptor Jürgen Weber (link in German). Six biblical scenes appear in the work. The pulpit was designed by German painter, restorer, and glass painter Valentin Peter Feuerstein. (link in German).

Stained glass windows by Klaus Arnold; Credit – Von Moleskine – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75940522

In 1966, Klaus Arnold (1928 – 2009), German sculptor, painter, and professor at Karlsruhe Art Academy, was commissioned to design the windows of the nave of Saint Michael’s Church. His colored stained glass windows are spectacular works of post-war modern art. Arnold complemented the early Gothic architecture with its heavy pillars and cave-like side aisles with a dark, glowing color palette of blue, red, and orange tones in the abstract stained glass windows.

********************

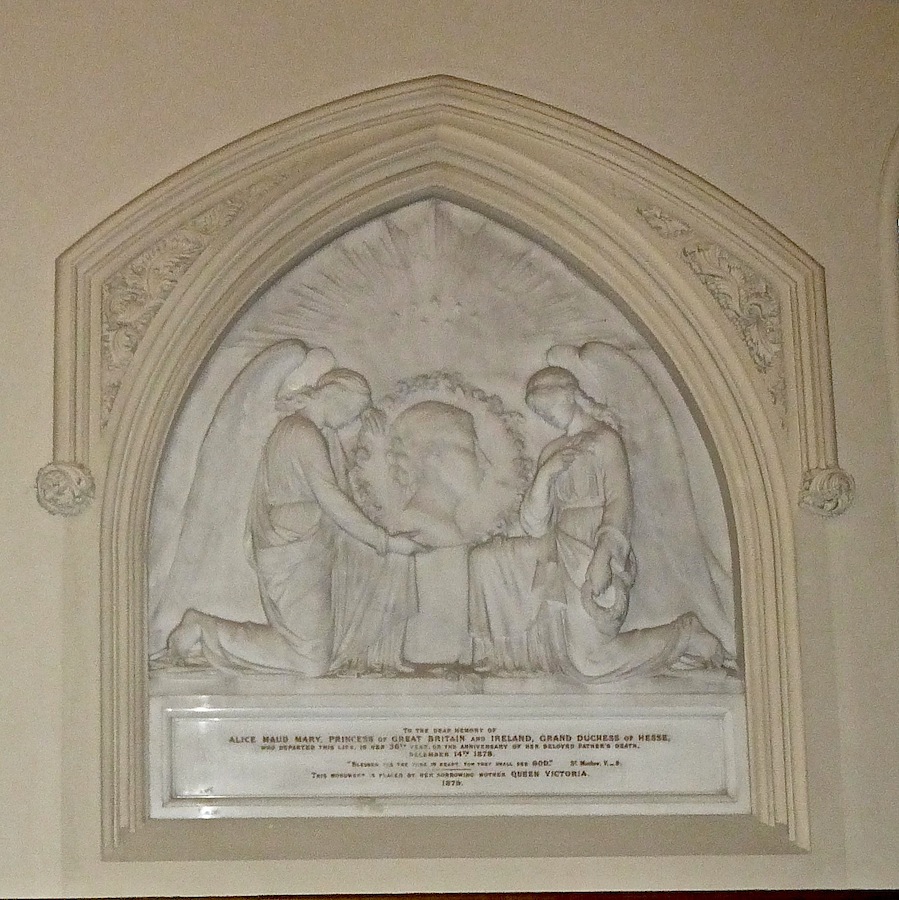

Burial Site

From 1538, Saint Michael’s Church was designated as the burial place of the Ernestine line of the House of Baden. Until 1860, almost all members of that branch of the House of Baden, which had become Protestant, were buried at St. Michael’s Church. The chancel contains grave markers of family members, and a two-chamber crypt is located under the floor.

1840 steel engraving by Louis Friedrich Hoffmeister – The Princely Crypt of the House of Baden in the St. Michael’s Church. In the center, brightly lit is August Moosbrugger’s 1833 monument to Karl Friedrich, first Grand Duke of Baden, which was destroyed in the World War II bombing. r; Credit – Wikipedia

Burials at Saint Michael’s Church

Note: This does not purport to be a complete list.

- Ursula of Rosenfeld (circa 1499 – 1538), second wife of Ernst I, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Ernst I, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1482 – 1553)

- Bernard IV, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1517 – 1553)

- Kunigunde of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1524 – 1558), wife of Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Marie of Baden-Durlach (1553 – 1561), daughter of Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach, died in childhood

- Anna Marie of Baden-Durlach (1565 – 1573), daughter of Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach, died in childhood

- Albrecht of Baden-Durlach (1555 – 1574), son of Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach, died in his teens

- Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1529 – 1577)

- Maria Cleopha of Baden-Durlach (1515 – 1580), daughter of Ernst I, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Anna of Pfalz-Veldenz, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1540 – 1586), wife of Karl II, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Jakob III, Margrave of Baden-Hachberg (1562 – 1590)

- Ernst Friedrich, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1560 – 1604)

- Friedrich zu Salm-Dhaun-Neufville (1547 – 1608)

- Juliane Ursula Wild und Rheingräfin zu Salm-Dhaun-Neufville, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1572 – 1614), first wife of Georg Friedrich, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Barbara of Württemberg, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1593 – 1627), first wife of Friedrich V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Eleonore zu Solms-Laubach (1605 – 1633), second wife of Friedrich V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Georg Friedrich, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1573 – 1638)

- Friedrich Kasimir of Baden-Durlach (1643 – 1644), infant son of Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Eleonore Katharine of Baden-Durlach (born and died 1646), infant daughter of Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Albrecht II Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach (1522 – 1557), son of Kasimir, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach

- Friedrich V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1594 – 1659)

- Maria Elisabeth of Waldeck-Eisenberg (1608 – 1643), third wife of Frederick V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Anna Maria zu Hohengeroldseck (1593 – 1649), fourth wife of Frederick V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Eleonore Friederike of Baden-Durlach (1653 – 1658), daughter of Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach, died in childhood

- Friedrich V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1594 – 1659)

- Friederike Christiane of Baden-Durlach (1658 – 1659), infant daughter of Karl Magnus of Baden-Durlach and granddaughter of Friedrich V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Christina Magdalena of the Palatinate-Zweibrücken, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1616 – 1662), wife of Frederick VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Friedrich Magnus of Baden-Durlach (born and died 1672), infant son of Friedrich VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Friederike Auguste of Baden-Durlach (1673 – 1674), infant daughter of Friedrich VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Elisabeth Eusebia of Fürstenberg (? – 1676), fifth wife of Frederick V, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Christine Sophie of Baden-Durlach (1674 – 1676), daughter of Friedrich VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlach, died in childhood

- Klaudia Magdalena Elisabeth of Baden-Durlach (1675 – 1676), infant daughter of Friedrich VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1617 – 1677)

- Friedrich Rudolf of Baden-Durlach (1681 – 1682), infant son of Karl Gustav of Baden-Durlach and grandson of Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Karl Gustav of Baden-Durlach (1648 – 1703), son of Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Friedrich VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1647 -1709)

- Christoph of Baden-Durlach (1684 – 1723), son of Friedrich VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Auguste Marie of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1649 – 1728), wife of Friedrick VII Magnus, Margrave of Baden-Durlack

- Friedrich of Baden-Durlach, Hereditary Prince of Baden-Durlach (1703 – 1732), son of Karl III Wilhelm, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Katharina Barbara of Baden-Durlach (1650 – 1733), daughter of Friedrich VI, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Magdalena Wilhelmine of Württemberg, Margravine of Baden-Durlach (1677 – 1742), wife of Karl III Wilhelm, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Princess Luise Auguste of Baden (born and died 1767), infant daughter of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden, from his first marriage

- Amalia of Nassau-Dietz, Hereditary Princess of Baden-Durlach (1710 – 1777), wife of Friedrich, Hereditary Prince of Baden-Durlach

- Karoline Luise of Hesse-Darmstadt, Margravine of Baden (1723 – 1783), 1st wife of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden

- Karl Friedrich of Baden-Durlach (1784 – 1785), infant son of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden

- Wilhelm Ludwig of Baden-Durlach (1732 – 1788), son of Prince Friedrich of Baden-Durlach and grandson of Karl III Wilhelm, Margrave of Baden-Durlach

- Friedrich Alexander of Baden (born and died 1793), infant son of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden, from his second marriage

- Karl Ludwig, Hereditary Prince of Baden (1755 – 1801), son of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden, from his first marriage

- Karl Friedrich of Baden (1728 – 1811), Margrave of Baden-Durlach (1738 – 1771), Margrave of Baden (1771–1803), Elector of the Holy Roman Empire (1803 – 1806), and first Grand Duke of Baden (1806 – 1811)

- Marie Elisabeth Wilhelmine of Baden, Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1782 – 1808), daughter of Karl Ludwig, Hereditary Prince of Baden and wife of Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- Unnamed son of Karl, Grand Duke of Baden (born and died 1812)

- Prince Alexander, Hereditary Grand Duke of Baden (born and died 1816), infant son of Karl, Grand Duke of Baden

- Prince Friedrich of Baden (1756 – 1817), son of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden, from his first marriage

- Karl I, Grand Duke of Baden (1786 – 1818)

- Luise Karoline Geyer von Geyersberg, Countess of Hochberg (1768 – 1820), 2nd wife of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden

- Prince Ludwig of Baden (born and died 1822), infant son of Leopold, Grand Duke of Baden

- Amalie Christine Luise of Baden (1776 – 1823), daughter of Karl Ludwig, Hereditary Prince of Baden, granddaughter of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden

- Christine Luise of Nassau-Usingen (1776 – 1829), wife of Prince Friedrich of Baden, son of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden

- Amalie of Hesse-Darmstadt, Hereditary Princess of Baden (1754 – 1832), wife of Karl Ludwig, Hereditary Prince of Baden

- Prince Wilhelm of Baden (1792 – 1859), son of Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden, from his second marriage

- Stéphanie de Beauharnais, Grand Duchess of Baden (1789 – 1860), wife of Karl I, Grand Duke of Baden

Works Cited

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2009). Deutscher Künstler. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klaus_Arnold_(Maler)

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2002). Großstadt in Baden-Württemberg, Deutschland. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pforzheim

- Autoren der Wikimedia-Projekte. (2004). Kirchengebäude in Pforzheim. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Michael_(Pforzheim)

- Black Forest Highlights. (2025). Blackforest-Highlights.com. https://www.blackforest-highlights.com/poi/detail/schloss-und-stiftskirche-st.-michael-9a0fa678e8

- Mehl, Scott. Baden Royal Burial Sites. (2017). Unofficial Royalty. https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/former-monarchies/german-royals/grand-duchy-of-baden/baden-royal-burial-sites/

- Die Schlosskirche St. Michael in Pforzheim. (2025). EKIBA. https://www.ekiba.de/detail/nachricht-seite/id/7224-/?cataktuell=407

- Schloßkirche — Förderverein Schloßkirche Pforzheim. (2022). Förderverein Schloßkirche Pforzheim. Förderverein Schloßkirche Pforzheim. https://www.foerderverein-schlosskirche.de/schlosskirche

- Schlosskirche Pforzheim. (2020). Schlosskirche-Pforzheim.guide. https://schlosskirche-pforzheim.guide/

- Schlosskirche St. Michael Pforzheim in Pforzheim, Baden-Württemberg – Find a Grave Cemetery. (2025). Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2190881/schlosskirche-st.-michael-pforzheim

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2024). Margraviate of Baden. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation

- Wikipedia Contributors. (2025). Pforzheim. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation.

- Współtwórcy projektów Fundacji Wikimedia. (2024, July 25). Kolegiata zamkowa św. Michała w Pforzheimie. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolegiata_zamkowa_%C5%9Bw._Micha%C5%82a_w_Pforzheimie

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.