by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Capuchin Church in Vienna (Cloister on left, Church in middle, Imperial Crypt on right); Credit – © Susan Flantzer

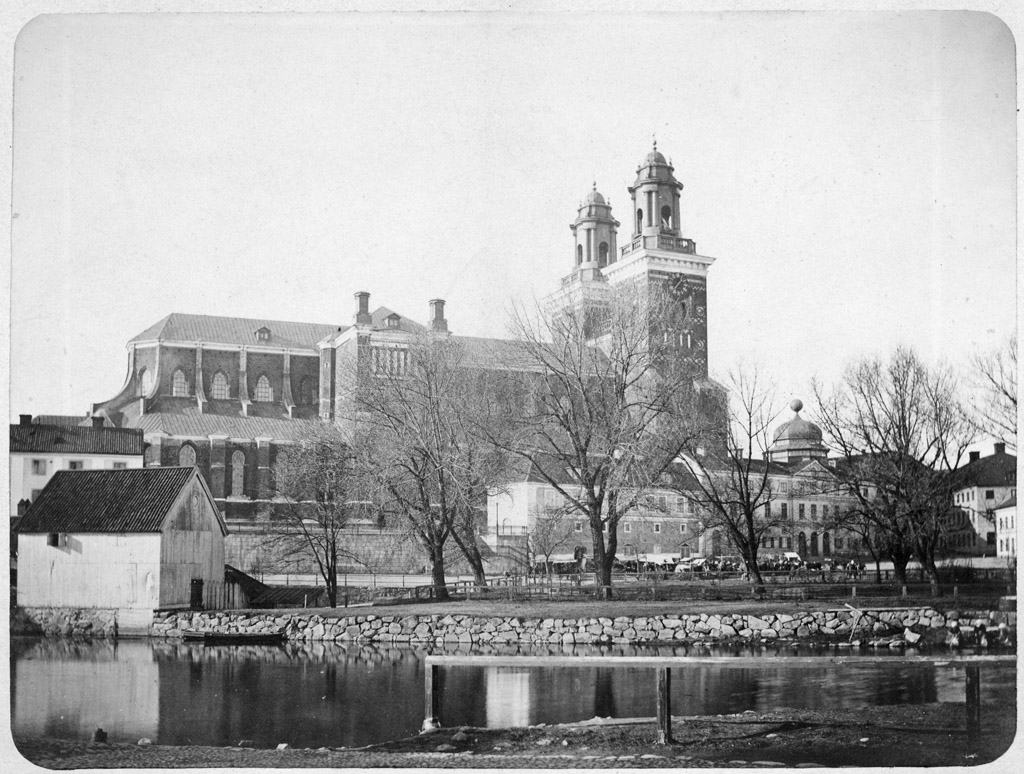

The Capuchin Church (German: Kapuzinerkirche), a Roman Catholic church in Vienna, Austria, which this writer has visited, contains the Imperial Crypt, the burial site for members of the House of Habsburg. The Imperial Crypt is in the care of the Capuchin monks from the cloister attached to the church. The burial place of the Habsburgs is so unlike the soaring structures containing the other burial sites I have visited and certainly not as grandiose. The Capuchin Church is small and is on a street with traffic, shops, stores, restaurants, and cafes. One cafe is directly across from it. Walking past the church, one would never think the burial place of emperors was there.

The Capuchin Church was founded by Anna of Tyrol and her husband Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor in 1617. Anna of Tyrol had come up with the idea of a Capuchin monastery and burial place for her and her husband and wanted to build it near Hofburg Palace in Vienna. In her will, Anna left funds to provide for the church’s construction. Anna died in December 1618, a year after she had made her will, and her husband Matthias died three months later. The foundation stone was laid in 1622, but the church was not completed and dedicated until 1632 because of the Thirty Years’ War. On Easter of 1633, the two sarcophagi containing the remains of Matthias and Anna were transferred to the Capuchin Church and placed in what is now called the Founders Vault.

*********************

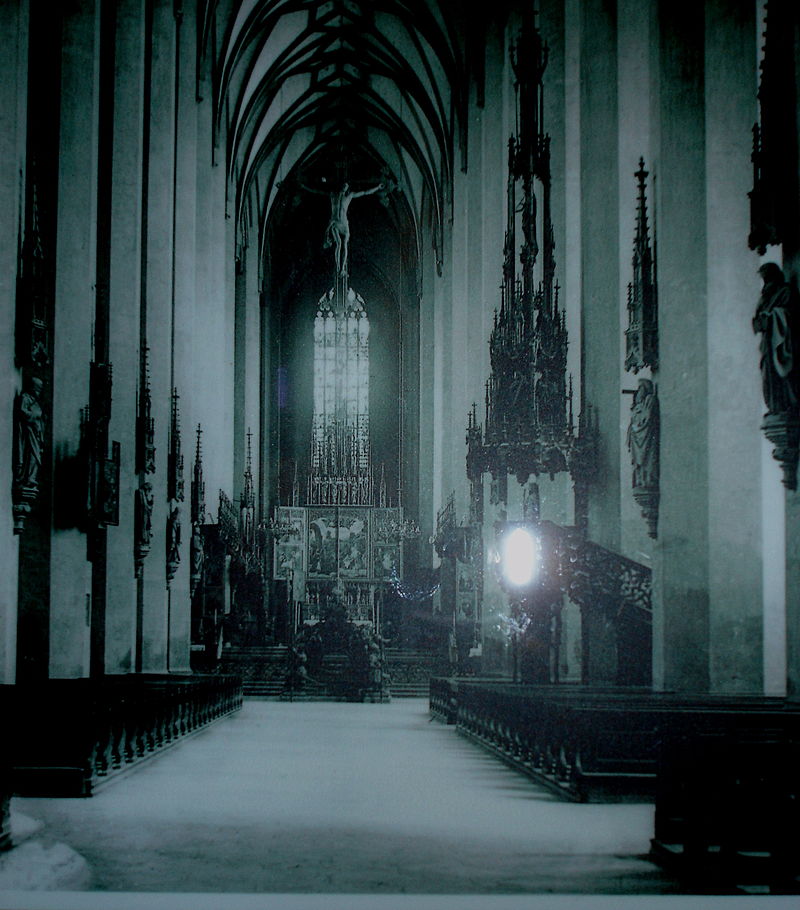

Interior of the Capuchin Church; Credit – Wikipedia

Although there have been renovations over the years, the main part of the church is more like a chapel with one main altar and two side altars. Father Norbert Baumgartner (1710 – 1773), a Capuchin friar at the cloister, painted the three altarpieces.

The High Altar; Credit – By Ricardalovesmonuments – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69156888

The right side altar is dedicated to St. Felix of Cantalice, the first Capuchin friar to be named a saint.

The right side altar; Credit – By Ricardalovesmonuments – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69156891

The left side altar is dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua.

The left side altar; Credit – By Ricardalovesmonuments – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69156894

Two side chapels contrast the simpler church. The Imperial Chapel contains a series of life-size statues of rulers from the House of Habsburg and a high altar with a painting of Mary, Help of Christians. The last heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Otto von Habsburg, who died in July 2011, and his wife Regina of Saxe-Meiningen, who died in 2010 but was temporarily interred elsewhere, lay in repose in the Imperial Chapel before their burial in the Imperial Crypt.

The coffins of Otto von Habsburg and his wife Regina of Saxe-Meiningen lying in repose in the Imperial Chapel; Credit – By Gryffindor – CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17173925

The Pietà Chapel has a marble altar with a life-size Pietà, created by Austrian sculptor and painter Peter Strudel. The statue was originally in the Imperial Crypt and was moved into the Pietà Chapel at the end of the 18th century. In the floor in front of the altar is the burial place of Blessed Marco d’Aviano, an Italian Capuchin friar beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2003. Marco d’Aviano’s name has often been given to Austrian royals and other Roman Catholic royals. See Wikipedia: Marco d’Aviano Honorary Protection.

The altar in the Pietà Chapel; Credit – By Ricardalovesmonuments – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69156907

*********************

What is Separate Burial?

A separate burial is a form of partial burial in which internal organs are buried separately from the rest of the body. Separate burials of the heart, viscera (the intestines), and the body were common in the House of Habsburg starting with the death of Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans in 1654 until the death of Archduke Franz Karl in 1878. Ferdinand IV of the Romans (1633 – 1654), son of Holy Emperor Ferdinand III, had a strong devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary and requested that his heart be interred in the Loreto Chapel at the Augustinekirche in Vienna. This established the tradition of interring the hearts of members of the Habsburg family in a crypt alongside the heart of Ferdinand IV. Until then, the hearts of Habsburgs had mostly been buried with the body in the coffin at the Imperial Crypt in the nearby Capuchin Church in Vienna or in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna where the entrails of the Habsburgs were traditionally interred. With the death of Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans, it became traditional for the body to be interred in the Imperial Crypt in the Capuchin Church in Vienna, the heart to be placed in an urn in the Herzgruft, the Heart Crypt in the Loreto Chapel of the Augustinerkirche in Vienna, and the entrails to be placed in an urn in the Ducal Crypt of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna.

After the end of the monarchy in 1918, some members of the Habsburg family resumed the tradition of heart burial but not viscera burial. When Karl I, the last Emperor of Austria, died in 1922, he was not allowed to be buried in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna and instead was buried at the Church of Our Lady of Monte on the island of Madeira in Portugal. His heart remained with his widow Empress Zita until it was interred in the Loreto Chapel of the Muri Monastery in Switzerland in 1971. When Empress Zita died in 1989, her body was buried in the Imperial Crypt at the Capuchin Church in Vienna and her heart was interred with her husband’s heart in the Loreto Chapel of the Muri Monastery in Switzerland. Karl and Zita’s son Otto von Habsburg, the last Crown Prince of Austria, requested that his heart be buried in the crypt of the Benedictine Abbey of Pannonhalma in Hungary. His body was interred in the Imperial Crypt at the Capuchin Church. The body of Otto’s wife Regina of Saxe-Meiningen was also interred in the Imperial Crypt but she requested that her heart be interred in her family’s crypt at Veste Heldburg (link in German) in Heldburg, Germany.

*********************

The Imperial Crypt is entered by descending the stairs marked by a sign “Zur Kaisergruft” (To the Imperial Crypt); Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Underneath the Capuchin Church lies the Imperial Crypt (German: Kaisergruft) which contains nearly 150 tombs of the Habsburg family. Through the years, additional vaults have been added and Capuchin friars still look after the tombs. By tradition, the bodies of the Habsburgs were buried at three locations. The hearts were interred in the Heart Crypt (German: Herzgruft) in the nearby Augustinerkirche in Vienna. The intestines were placed in copper urns in the Ducal Crypt (German: Herzogsgruft) of the Catacombs in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Their bodies were entombed in the Imperial Crypt. All the caskets and tombs in the Imperial Crypt are labeled in German with the identity of the person and the relationship to a Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of Austria, or Archduke.

Read more about my visit to the Imperial Crypt at Unofficial Royalty: A Visit to the Kaisergruft (Imperial Crypt) in Vienna.

Credit – Wikipedia

A. Founders Vault: is the oldest part of the Imperial Crypt, dating from the original construction of the church which was completed in 1632.

B. Children’s Columbarium: was built in the 1960s and contains the sarcophagi of 12 children who had previously been in either the Founders Vault or the main hall of Leopold’s Vault

C. Leopold’s Vault: was built under the nave of the Capuchin Church beginning in 1657 by Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I following the edict of his father Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III that the hereditary burial place of the imperial family would be in the Capuchin Church.

D. Karl’s Vault: was built in 1710 by Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I and extended in 1720 by Holy Roman Emperor Karl VI

E. Maria Theresa’s Vault: started construction in 1754. It is behind the Capuchin Church with its dome rising into the cloister courtyard.

F. Franz’s Vault: was built in 1824 by former Holy Roman Emperor Franz II, now Emperor Franz I of Austria. The octagonal Franz’s Vault is attached to the right wing of the Maria Theresa Vault.

G. Ferdinand’s Vault: was built in 1842, along with the Tuscan Vault, in conjunction with the reconstruction of the cloister above. There are only two visible sarcophagi but Ferdinand’s Vault contains one-fourth of the Imperial Crypt’s burials, walled up into the corner piers.

H. New Vault: was built between 1960 and 1962 under the monastery grounds as an enlargement to eliminate overcrowding in the other nine vaults, and to provide a climate-controlled environment to protect the metal sarcophagi from further deterioration.

I. Franz Joseph’s Vault: and the adjacent crypt chapel (J) were built in 1908 as part of the celebrations of Emperor Franz Joseph’s 60 years on the throne.

J. Crypt Chapel: The Crypt Chapel was built, along with the Franz Joseph Vault, in 1908. It is usually entered from the south doorway of the Franz Joseph Vault. The most recent burials are here.

K. The Tuscan Vault: was built in 1842, along with the Ferdinand Vault. This vault takes its name from burials here of the many descendants of the younger sons of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, who reigned as Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1765 – 1790, before he became Holy Roman Emperor.

Founders Crypt

Tombs of Holy Roman Emperor Matthias and his wife Anna of Tyrol, Holy Roman Empress; Credit – Von Welleschik – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6619836

Located under the Imperial Chapel, the Founders Crypt is the oldest part of the Imperial Crypt, dating from the original construction of the Capuchin Church. The Founders Crypt cannot be entered by visitors and is visible through a gate from the Leopold Crypt. It contains the two sarcophagi of the founders of the Capuchin Church.

Leopold’s Crypt

Leopold’s Crypt; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Leopold’s Crypt was built under the nave of the Capuchin Church beginning in 1657 by Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I following the edict of his father Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III that the burial place of the House of Habsburg would be at the Capuchin Church.

- Maria Anna of Spain, Holy Roman Empress (1606 – 1646) – 1st wife of Holy Emperor Ferdinand III

- Maria Leopoldine of Austria, Holy Roman Empress (1632 – 1649) – 2nd wife of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Ferdinand IV, King of Bohemia, King of Hungary and Croatia, King of the Romans (1633-1654) – eldest son of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III (1608 – 1657)

- Claudia Felicitas of Austria-Tyrol, Holy Roman Empress (1653 – 1676) – 2nd wife of Holy Emperor Leopold I, heart urn interred, at her request, dressed in the habit of a Dominican nun, she was entombed beside her mother in the Dominican Church in Vienna

- Archduke Leopold Joseph of Austria (1682 – 1684) – son of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Eleonora Magdalena Gonzaga of Mantua, Holy Roman Empress (1630 – 1686) – 3rd wife of Holy Emperor Ferdinand III

- Maria Anna Josepha of Austria, Electress of the Palatinate (1654 -1689) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Margarita Teresa of Spain, Holy Roman Empress (1651 – 1673) – 1st wife of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I

- Maria Antonia of Austria, Electress of Bavaria (1669 – 1692) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I

- Archduchess Maria Theresia of Austria (1684 – 1696) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I

- Eleonora Maria of Austria, Queen of Poland (1653–1697 – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, wife of King Michael of Poland

- Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria (1687 – 1703) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I

- Archduke Leopold Johann of Austria (born and died 1716) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Karl VI

- Eleonora Magdalena of Pfalz-Neuburg, Holy Roman Empress (1655 – 1720) – 3rd wife of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I

- Archduchess Maria Amalia of Austria (1724 – 1730) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Karl VI

- Archduchess Maria Magdalena of Austria (1689 – 1743) – daughter of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Maria Anna of Austria, Queen of Portugal (1683 – 1754) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, wife of King João V of Portugal, heart urn interred, her body was buried at the Monastery of St. John Nepomuk of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon, Portugal, which she founded

Children’s Columbarium

Children’s Columbarium; Credit – By Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada – Austria-00826 – Emperor Tomb, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66921927

In the 1960s, the Children’s Columbarium, twelve niches in the wall of Leopold’s Crypt, was built for the coffins of twelve young children. The coffins were originally in the Founders Crypt or Leopold’s Crypt.

- Archduke Philipp August of Austria (1637 – 1639) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Archduke Maximilian Thomas of Austria (born and died 1639) – son of Holy Emperor Ferdinand III

- Archduchess Theresia Maria of Austria (1652 – 1653) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Archduke Ferdinand Josef of Austria (1657 – 1658) – son of Holy Emperor Ferdinand III

- Archduke Ferdinand Wenzel of Austria (1667 – 1668) – son of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Archduke Johann Leopold of Austria (born and died 1670) – son of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria (born and died 1672) – daughter of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Archduchess Anna Maria Sophia of Austria (born and died 1674) – daughter of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Archduchess Maria Josepha (1675 – 1676) – daughter of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Archduchess Christina of Austria (born and died 1679) – daughter of Holy Emperor Leopold I

- Unnamed (born and died 1686) – son of Johann Wilhelm of Pfalz-Neuberg and Archduchess Maria Anna Josepha of Austria and grandson of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Archduchess Maria Margareta of Austria (1690 – 1691) – daughter of Holy Emperor Leopold I

Karl’s Crypt

Tomb of Karl VI, Holy Roman Emperor; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

What is now known as Karl’s Crypt was first built in 1710 by Holy Roman Emperor Joseph. In 1720, the crypt was enlarged on the orders of Holy Roman Emperor Karl VI. Karl VI’s famous tomb has a death’s head at each corner wearing one of the crowns of his major realms, the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Kingdom of Hungary, and the Archduchy of Austria.

Maria Theresa’s Crypt

Tomb of Maria Theresa and her husband with the tomb of their son Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II in the foreground; Credit – By Wotau – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 at, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21894136

A Note About Maria Theresa: Born Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria, she was the second and eldest surviving child of Holy Roman Emperor Karl VI. Her only brother died several weeks before she was born and her two younger siblings were sisters. The fact that Maria Theresa’s father did not have a male heir caused many problems. Maria Theresa’s right to succeed to her father’s Habsburg territories in her own right was the cause of the eight-year-long War of the Austrian Succession. Upon her father’s death in 1740, Maria Theresa became the sovereign in her own right of all the Habsburg territories which included Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Transylvania, Mantua, Milan, Lodomeria and Galicia, the Austrian Netherlands, and Parma. However, she was unable to become the sovereign of the Holy Roman Empire because she was female. The Habsburgs had been elected Holy Roman Emperors since 1438, but in 1742 Karl Albrecht, Duke of Bavaria and Prince-Elector of Bavaria from the Bavarian House of Wittelsbach was elected Holy Roman Emperor Karl VII. He died in 1745 and via a treaty Maria Theresa arranged for her husband Francis Stephen, Duke of Lorraine to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. Despite the snub, the formidable Maria Theresa wielded the real power and in reality, ruled the Holy Roman Empire. She is generally referred to by historians simply as Empress Maria Theresa and that is how she is referred to in this article. Maria Theresa and her husband had sixteen children. Eight of the couple’s children died in childhood and four of the eight died from smallpox.

Construction of the Maria Theresa Crypt started in 1754. It is located behind the Capuchin Church with its dome rising into the monastery courtyard.

Franz’s Crypt

Tomb of Holy Roman Emperor Franz II/Emperor Franz I of Austria; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Holy Roman Emperor Franz II = Emperor Franz I of Austria: Upon the death of his father Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II in 1792, Franz was elected the last Holy Roman Emperor and reigned as Holy Roman Emperor Franz I. Franz feared that Napoleon Bonaparte could take over his personal Habsburg territories within the Holy Roman Empire, so in 1804 he proclaimed himself Emperor Franz I of Austria and reigned until his death in 1835. Franz’s decision proved to be a wise one. Two years later, after Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved and lands that had been held by the Holy Roman Emperor were given to Napoleon’s allies creating the Kingdom of Bavaria, the Kingdom of Württemberg, and the Grand Duchy of Baden. Franz is referred to as Emperor Franz I of Austria in this article.

In 1824, Emperor Franz I of Austria built the octagonal Franz’s Crypt attaching it to the Maria Theresa Crypt. The crypt contains the tomb of Franz surrounded by the caskets of his four wives (two died in childbirth, one died of tuberculosis, and one survived him) in the crypt’s corners.

Tomb of Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily, second wife of Emperor Franz I of Austria and the mother of his children. Maria Theresa died giving birth to her twelfth child who also died; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Ferdinand’s Crypt

Tomb of Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria; Credit – By Jebulon – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19158475

Ferdinand’s Crypt was built in 1842, along with the Tuscan Crypt, during the renovation of the monastery which is above the crypt. Only two sarcophagi, those of Emperor Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Maria Anna of Savoy, are visible, but 25% of the tombs in the Imperial Crypt are interred in the walls of Ferdinand’s Crypt.

Sarcophagi placed in the vault:

Interred in wall niches:

- Archduchess Ludovica Elisabeth of Austria (1790 – 1791) – daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduchess Karoline Leopoldine of Austria (1794 – 1795) – daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduke Alexander Leopold of Austria (1772 – 1795) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduchess Maria Amalia of Austria (1780 – 1798) – daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduchess Karoline Louise of Austria (1795 – 1799) – daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Luisa of Naples and Sicily, Grand Duchess of Tuscany (1773 – 1802), granddaughter of Empress Maria Theresa, first wife of Ferdinando III, Grand Duke of Tuscany

- Archduchess Amalie Therese of Austria (born and died 1807) – daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduke Joseph Franz of Austria (1799 – 1807) – son of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduke Johann Nepomuk Karl of Austria (1805 – 1809) – son of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduchess Karoline Ferdinanda of Austria (1793 – 1802), daughter of Grand Duke Ferdinand III of Tuscany and granddaughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria (1835 – 1840) – sister of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

- Archduchess Maria Karolina of Austria (1821 – 1844) – daughter of Archduke Rainer of Austria and granddaughter of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduchess Sophie Friederike of Austria (1855 – 1857) – daughter of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

- Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria (1804 – 1858) – daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduchess Maria Eleonore of Austria-Teschen (born and died 1864) – daughter of Archduke Karl Ferdinand of Austria-Teschen

- Maria Ferdinanda of Saxony, Grand Duchess of Tuscany (1796 – 1865) – 2nd wife of Grand Duke Ferdinand III of Tuscany

- Archduchess Maria Antoinetta of Austria (1858 – 1883) – daughter of Grand Duke Ferdinand IV of Tuscany

- Archduchess Henriette Maria of Austria (1884 – 1886) – daughter of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Archduke Rainer Salvator of Austria (1880 – 1889) – son of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Archduchess Stephanie of Austria (1886 – 1890) – daughter of Archduke Friedrich of Austria, Duke of Teschen

- Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria (1874 – 1891) – daughter of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Archduke Ferdinand Salvator of Austria (1888 – 1891) – son of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria (1839 – 1892) – son of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany

- Archduke Robert Ferdinand (1885 – 1895) – son of Grand Duke Ferdinand IV of Tuscany

- Archduke Albrecht Salvator of Austria (1871 – 1896) – son of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Archduchess Natalie of Austria (1884 – 1898) – daughter of Archduke Friedrich of Austria, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Leopold of Austria (1823 – 1898) – son of Archduke Rainer of Austria and grandson of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Maria Antonia of the Two Sicilies, Grand Duchess of Tuscany (1814 – 1898) – 2nd wife of Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany

- Maria Immaculata of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Archduchess of Austria (1844 – 1899) – wife of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Archduke Ernst of Austria (1824 – 1899) – son of Archduke Rainer of Austria and grandson of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Adelgunde of Bavaria, Duchess of Modena (1823 – 1914) – wife of Francesco V, Duke of Modena

- Archduchess Marie Caroline of Austria-Teschen (1825 – 1915) – daughter of Archduke Karl, Duke of Teschen and wife of Archduke Rainer Ferdinand of Austria

- Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria (1847 – 1915) – son of Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany

- Archduke Joseph Ferdinand of Austria (1872 – 1942) – son of Grand Duke Ferdinand IV of Tuscany

- Maria Theresa of Portugal, Archduchess of Austria (1855 – 1944) – 3rd wife of Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria, brother of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria

- Archduke Leopold of Austria (1897 – 1958) – son of Archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria

Tuscan Crypt

Tuscan Crypt; Credit – By Welleschik – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6656990

The Tuscan Crypt was built in 1842 at the same time as the Ferdinand Vault. The vault takes its name from the many descendants of the younger sons of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II. Leopold reigned as Pietro Leopoldo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1765 – 1790. He abdicated as Grand Duke of Tuscany in favor of his second son Ferdinando when he was elected Holy Roman Emperor.

- Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II (1747 – 1792), reigned 1765 – 1790 as Pietro Leopoldo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany, abdicated in favor of his son Ferdinando when he was elected Holy Roman Emperor

- Maria Luisa of Spain, Holy Roman Empress (1745 – 1792) – wife of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduchess Maria Christina of Austria, Duchess of Teschen (1742 – 1798) – daughter of Empress Maria Theresa and wife of Prince Albrecht of Saxony, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Ferdinand Karl of Austria-Este (1754 – 1806) – son of Empress Maria Theresa, husband of Maria Beatrice d’Este, the heiress of Modena and Reggio, founders of the House of Austria-Este

- Maria Carolina of Austria, Queen of Naples and Sicily (1752 – 1814) – daughter of Empress Maria Theresa and 1st wife of King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Sicily

- Albert, Duke of Saxony-Teschen (1738 – 1822) – husband of Archduchess Maria Christina of Austria

- Maria Beatrice d’Este, Duchess of Massa, Archduchess of Austria (1750 – 1829) – wife of Archduke Ferdinand Karl of Austria-Este

- Archduke Anton Viktor of Austria (1779 – 1835) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduke Ferdinand Karl Joseph of Austria-Este (1781 – 1850) – son of Archduke Ferdinand Karl of Austria-Este

- Archduke Ludwig Joseph of Austria (1784 – 1864) – son of Holy Emperor Leopold II

- Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1797 – 1870)

- Francesco V, Duke of Modena (1819 – 1875)

- Ferdinand IV, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1835 – 1908)

- Archduke Rainer Ferdinand of Austria (1827 – 1913) – son of Archduke Rainer Joseph of Austria and grandson of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

New Crypt

New Crypt: Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

The New Crypt was built under the monastery grounds from 1960 – 1962 to provide more space. The two most famous tombs in the New Vault stand directly across from each other: Empress Marie-Louise of France, daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria and the second wife of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French and Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, second son of Archduke Franz Karl and brother of Emperor Franz Joseph. Emperor Maximilian of Mexico was deposed and executed by a firing squad.

- Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria (1614 – 1662) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II

- Archduke Karl Joseph of Austria (1649 – 1664) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Karl Joseph of Lorraine, Archbishop and Prince-Elector of Trier (1680 – 1715) – son of Archduchess Eleonora Maria of Austria and grandson of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III

- Archduke Maximilian Franz of Austria, Archbishop and Elector of Cologne, (1756 – 1801) – son of Empress Maria Theresa

- Archduke Rudolf of Austria (born and died 1822) – son of Archduke Karl of Austria, Duke of Teschen

- Henrietta of Nassau-Weilburg, Archduchess of Austria (1797 – 1829) – wife of Archduke Karl of Austria, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Rudolph of Austria, Cardinal-Archbishop of Olomouc (1788 – 1831) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Unnamed stillborn son (1840) – son of Archduke Franz Karl of Austria and grandson of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Archduke Karl of Austria, Duke of Teschen (1771 – 1847) – son of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II

- Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, Empress of the French (1791 – 1847) – daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria, 2nd wife of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French

- Archduke Karl Albrecht of Austria (1847 – 1848) – son of Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen

- Margaretha of Saxony, Archduchess of Austria (1840 – 1858) – 1st wife of Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria

- Hildegard of Bavaria, Archduchess of Austria, Duchess of Teschen (1825–1864) – wife of Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen

- Archduchess Mathilde of Austria-Teschen (1849 – 1867) – daughter of Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Maximilian of Austria, Emperor Maximilian of Mexico (1832- 1867) – son of Archduke Franz Karl of Austria, grandson of Emperor Franz I of Austria

- Maria Annunciata of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Archduchess of Austria (1843 – 1871) – 2nd wife of Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria

- Sophie of Bavaria, Archduchess of Austria (1805 – 1872) – wife of Archduke Franz Karl of Austria and mother of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

- Archduke Karl Ferdinand of Austria-Teschen (1818 – 1874) – son of son of Archduke Karl, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Franz Karl of Austria (1802 – 1878) – son of Emperor Franz I of Austria and father of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

- Archduke Wilhelm of Austria-Teschen (1827 – 1894) – son of Archduke Karl, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Albrecht of Austria, Duke of Teschen (1817 – 1895) – son of Archduke Karl, Duke of Teschen

- Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria (1833 – 1896) – son of Archduke Franz Karl of Austria, brother of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, father of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

- Archduke Otto of Austria (1865 – 1906) – son of Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria, nephew of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, father of Karl I, the last Emperor of Austria

- Archduke Rainer Karl of Austria (1895 – 1930) – son of Archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria

- Archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria (1863 – 1931) – son of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria

- Maria Josepha of Saxony, Archduchess of Austria (1867 – 1944) – wife of Archduke Otto of Austria and mother of Karl I, the last Emperor of Austria

Franz Joseph’s Crypt

Left to Right: Tombs of Empress Elisabeth, Emperor Franz Joseph I, and Crown Prince Rudolf; Credit – By Bwag – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 at, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28243562

In 1908, Franz Joseph’s Crypt was built along with the adjacent Crypt Chapel in celebration of Emperor Franz Joseph’s sixty years on the throne. Currently, Franz Joseph, with a reign of 67 years and 355 days, is the sixth longest-reigning monarch in history. Along with Franz Joseph’s tomb, the crypt contains the tombs of his wife Elisabeth of Bavaria, known as Sissi, who was assassinated, and their only son Crown Prince Rudolf who died by suicide along with his mistress Baroness Mary Vetsera at his Mayerling hunting lodge.

Crypt Chapel

Crypt Chapel; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

The Crypt Chapel, where the most recent interments have occurred, was built in 1908 along with Franz Joseph’s Crypt. Zita of Bourbon-Parma, the wife of Karl I, the last Emperor of Austria, two of her sons Otto and Carl Ludwig, and Otto’s wife Regina of Saxe-Meiningen are buried here. There is a space reserved for Carl Ludwig’s widow Princesse Yolande de Ligne. The Crypt Chapel contains a memorial to Emperor Karl I, who has been beatified by the Roman Catholic Church and who is buried at the Church of Our Lady of Monte on the island of Madeira, Portugal. There is also a memorial to Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg. Both were assassinated at Sarajevo, an event that was one of the causes of World War I. Franz Ferdinand and his wife are buried at Artstetten Castle in Austria.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2021. Kaisergruft – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaisergruft> [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- De.wikipedia.org. 2021. Kapuzinerkirche (Wien) – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapuzinerkirche_(Wien)> [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Capuchin Church, Vienna – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capuchin_Church,_Vienna> [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Imperial Crypt – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Crypt> [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2012. A Visit to the Kaisergruft (Imperial Crypt) in Vienna. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/royal-burial-sites/austrian-imperial-burial-sites/a-visit-to-the-kaisergruft-imperial-crypt-in-vienna/> [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2012. Burial Sites – House of Habsburg-Lorraine: Emperors of Austria. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/royal-burial-sites/austrian-imperial-burial-sites/house-of-habsburg-lorraine-emperors-of-austria/> [Accessed 22 December 2021].