by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Notre-Dame Cathedral in Luxembourg City; Credit – By Francisco Anzola – Notre Dame, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32183261

Notre Dame Cathedral is a Roman Catholic church in Luxembourg City, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Luxembourg was under Habsburg rule from 1444 – 1794 and then under French rule from 1794 -1815. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Luxembourg was made a Grand Duchy and united in a personal union with the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The King of the Netherlands was also the Grand Duke of Luxembourg. The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg remained in personal union with the Netherlands until the death of King Willem III of the Netherlands in 1890. His successor was his daughter Wilhelmina who could not inherit the throne of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg due to the Salic Law which prevented female succession. The new Grand Duke of Luxembourg was Adolphe who had been Duke of Nassau until it was annexed to Prussia in 1866. The Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg was then, and still is, a member of the House of Nassau-Weilburg.

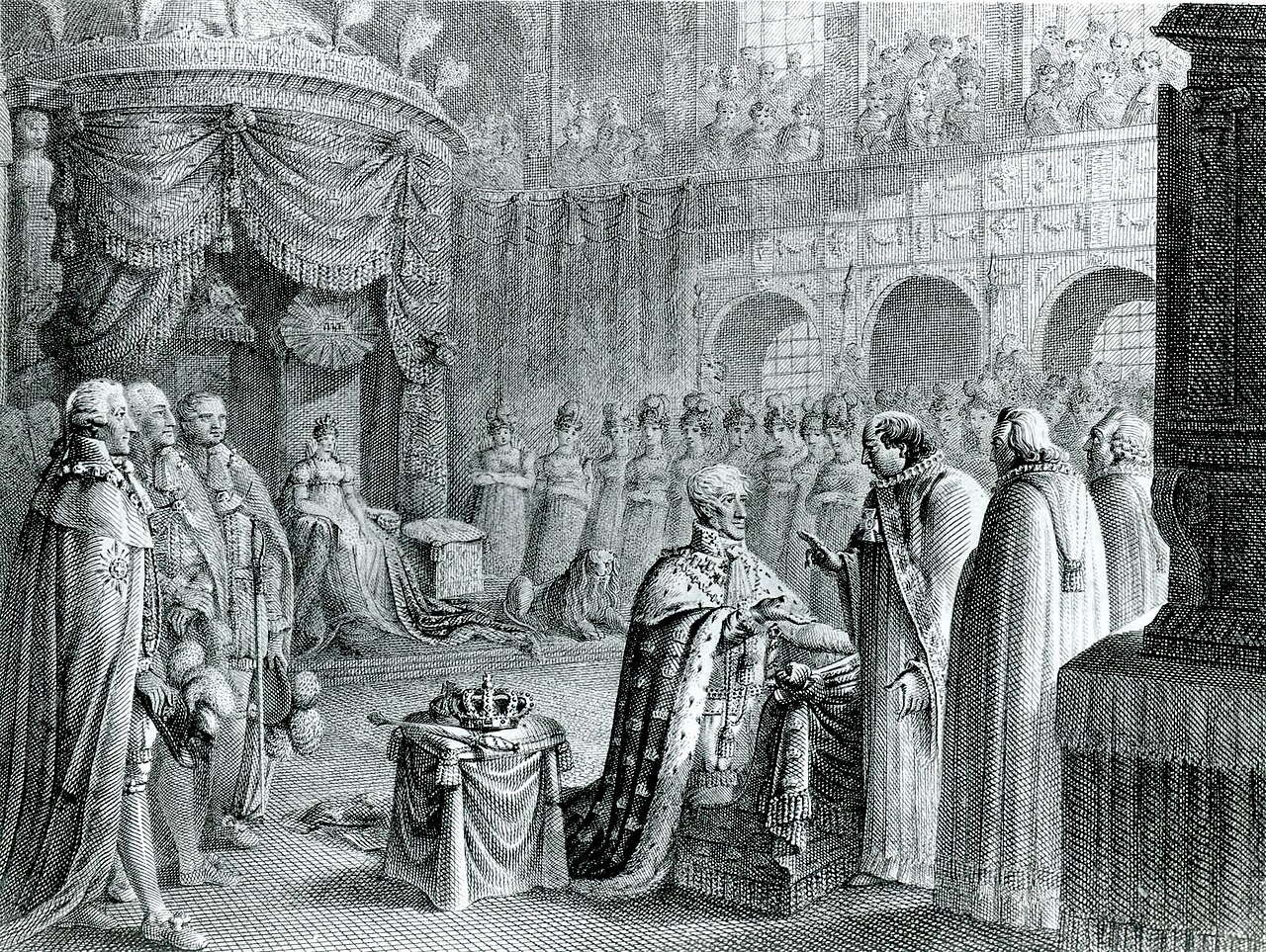

The Jesuit College of Luxembourg and its church in 1686; Credit – Wikipedia

The late Gothic style church was originally built for the Jesuit College of Luxembourg, (link in French) a Catholic Jesuit secondary school for boys. The church cornerstone was laid in 1613 and the church was consecrated and dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary in 1621. In 1773, the Jesuit order was suppressed and the school became the secular Luxembourg Athenaeum which is still in existence. At that time, the Habsburg ruler, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria gave the church to Luxembourg City.

The church became a parish church in 1778 under the name St. Nicolas and St. Thérèse, In 1801, the church once again changed its name to St. Peter before receiving its final name in 1848, Notre-Dame, French for Our Lady, referring to the Virgin Mary. In 1870, when Luxembourg became a diocese, Notre-Dame Church became Notre-Dame Cathedral and Nikolaus Adames became the first Bishop of Luxembourg. In 1988, the Diocese of Luxembourg was raised to an Archdiocese and Jean Hengen became the first Archbishop of Luxembourg.

Notre-Dame Cathedral in Luxembourg City; Credit – By Ich (Jeff Croisé) – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33037478

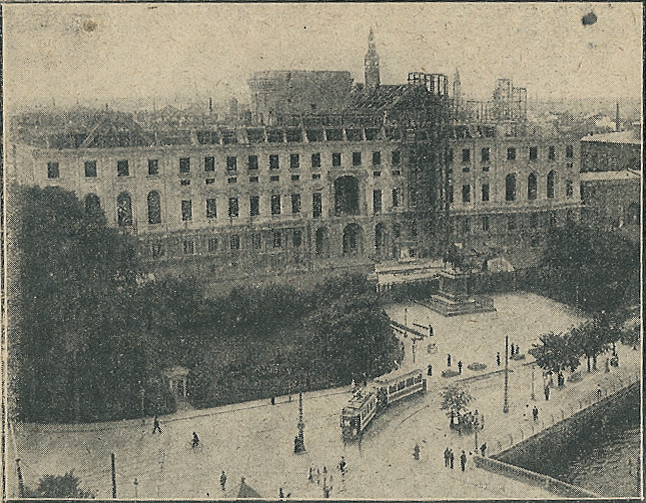

From 1935 to 1938 the cathedral was enlarged and expanded using the plans of the Luxembourgish architect Hubert Schumacher (link in German) who also supervised the construction. The west tower, the original tower of the Jesuit church which contains the bells, was joined by two new towers, the east tower and the central tower which stands over the transept. A crypt was built under the choir for the tombs of the Bishops and Archbishops of Luxembourg.

Interior of Notre-Dame Cathedral; Credit – By Johnny Chicago at lb.wikipedia – Own workTransferred from lb.wikipedia., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=644978

Another crypt was built for the Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg. The entrance to the Grand Ducal Crypt is marked by a gate with two bronze lions on either side designed by the Luxembourgish sculptor and painter Auguste Trémont (link in French).

Entrance to the Grand Ducal Crypt; Credit – By Joachim Specht – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44552120

Because the first three Grand Dukes of Luxembourg were also Kings of the Netherlands and Protestant, they were buried at the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) in Delft, the Netherlands, the traditional burial place of the Dutch Royal Family. Grand Duke Adolphe, his wife Adelheid-Marie of Anhalt-Dessau, and their son Grand Duke Guillaume were also Protestant and were all buried at the Castle Chuch of Schloss Weilburg, the former residence of the Counts and Dukes of Nassau-Weilburg, now in Weilburg, Hesse, Germany. However, because the majority of his subjects were Roman Catholic, Grand Duke Guillaume married the Roman Catholic Infanta Marie Anne of Portugal and their six daughters were raised in the Catholic religion. Since then, the Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg has been Roman Catholic.

Interior of the Grand Ducal Crypt; Credit – Par Abbaca — Travail personnel, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74928427

Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde of Luxembourg, who reigned 1912 – 1919, was the first family member to be buried in the Grand Ducal Crypt after she died of influenza in 1924 at the age of 29. However, there are royal remains in the Grand Ducal Crypt that are much older. In 1945, the remains of Jean of Bohemia, Count of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia were removed from his burial place and reinterred with military honors in the Grand Ducal Crypt of Notre-Dame Cathedral. Born in Luxembourg in 1296, Jean is famous for having died while fighting in the Battle of Crécy at age 50, after having been blind for a decade. He is considered a Luxembourg national hero.

Tomb of Jean of Bohemia, Count of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia; Credit – By Dudva – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79558829

Royal Weddings at Notre-Dame Cathedral

Wedding of Prince Guillaume, Hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg and Countess Stéphanie de Lannoy in 2012; Credit – Grand Ducal Court, photo: Vic Fischbach

- November 6, 1919: Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg married her first cousin, Prince Felix of Bourbon-Parma

- August 17, 1950: Princess Alix of Luxembourg married Antoine, 13th Prince de Ligne

- April 9, 1953: Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg married Princess Joséphine-Charlotte of Belgium – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of Grand Duke Jean and Princess Joséphine-Charlotte of Belgium

- May 9, 1956: Princess Elisabeth of Luxembourg married Franz, Duke of Hohenberg

- April 10, 1958: Princess Marie-Adélaïde of Luxembourg married Count Karl Josef Henckel von Donnersmarck

- February 14, 1981: Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg married Maria Teresa Mestre y Batista Falla – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of Grand Duke Henri and Maria Teresa Mestre y Batista Falla

- February 6, 1982: Princess Marie-Astrid of Luxembourg married her second cousin, Archduke Carl Christian of Austria

- March 20, 1982: Princess Margaretha of Luxembourg married Prince Nikolaus of Liechtenstein

- October 20, 2012: Prince Guillaume, Hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg married Countess Stéphanie de Lanoy – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of Hereditary Grand Duke Guillaume and Countess Stéphanie de Lannoy

Royal Burials at Notre-Dame Cathedral

Grand Duke Jean’s coffin resting in the Ducal Crypt after his funeral in 2019. Memorial plaques for family members are on the wall; Photo – www.cathol.lu

- Jean of Bohemia, Count of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia (1296 – 1346)

- Marie-Adélaïde, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, daughter of Grand Duke Guillaume (1894 – 1924) – abdicated in 1919 in favor of her sister Charlotte

- Maria Ana of Portugal, wife of Grand Duke Guillaume (1861 – 1942) – Maria Ana fled with her family when the German Army invaded Luxembourg in 1940. She died in New York City on July 31, 1942, and was temporarily interred at Calvary Cemetery in Queens in New York City. Her remains were later returned to Luxembourg and buried at Notre-Dame Cathedral.

- Felix of Bourbon-Parma, Prince Consort of Luxembourg, husband of Grand Duchess Charlotte I (1893 – 1970)

- Prince Charles of Luxembourg, son of Grand Duchess Charlotte (1927 – 1977)

- Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, daughter of Grand Duke Guillaume (1896 – 1985)

- Joséphine Charlotte of Belgium, wife of Grand Duke Jean (1927 – 2005)

- Jean, Grand Duke of Luxembourg, son of Grand Duchess Charlotte (1921 – 2019) – Unofficial Royalty: Funeral of Grand Duke Jean

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Notre-Dame Cathedral, Luxembourg – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Notre-Dame_Cathedral,_Luxembourg> [Accessed 11 September 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan and Mehl, Scott, 2012. Luxembourg Royal Burial Sites. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/royal-burial-sites/luxembourg-royal-burial-sites/> [Accessed 11 September 2021].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2021. Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Luxembourg — Wikipédia. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cath%C3%A9drale_Notre-Dame_de_Luxembourg> [Accessed 11 September 2021].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2021. Collège jésuite de Luxembourg — Wikipédia. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coll%C3%A8ge_j%C3%A9suite_de_Luxembourg> [Accessed 11 September 2021].