by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula; Credit – By I, Luc Viatour, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4789498

While the construction of the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, a Roman Catholic Church in Brussels, Belgium, which this writer has visited, began in 1226, its connection with the Kingdom of Belgium is short because Belgium has been a country only since 1830. In August 1830, the southern provinces (modern-day Belgium) of the Kingdom of the Netherlands rebelled against Dutch rule. International powers meeting in London agreed to support the independence of Belgium, even though the Dutch refused to recognize the new country. On April 22, 1831, Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, the uncle of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and her husband Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, was asked by the Belgian National Congress if he wanted to be king of the new country. Leopold swore allegiance to the new Belgian constitution on July 21, 1831, and became the first King of the Belgians. Under the Belgian Constitution, the Belgian monarch is styled “King/Queen of the Belgians” to reflect that the monarch is “of the Belgian people.”

The various predecessor states of the Kingdom of Belgium whose royalty also used the cathedral will be noticed below in the listing of royal events that occurred at the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula over the centuries. Before 1830, going back to the twelfth century, the predecessor states of Belgium were:

- Duchy of Brabant – a state of the Holy Roman Empire established in 1183. It developed from the Landgraviate of Brabant and formed the core of the historic Low Countries. It was part of the Burgundian Netherlands and the Habsburg Netherlands. Today, the title of Duke or Duchess of Brabant is the title of the heir apparent to the Belgium throne.

- Burgundian Netherlands (1384 – 1482) – Holy Roman Empire and French fiefs ruled in personal union by the Dukes of Burgundy of the House of Valois-Burgundy and later by their Habsburg heirs.

- Habsburg Netherlands (1482 – 1797) is the collective name of Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire’s House of Habsburg.

- Spanish Netherlands (1556 – 1714) – was the name for the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714

- Austrian Netherlands (1714 – 1797) – was the name for the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by Governors from the Austrian House of Habsburg. It existed from the end of the Spanish War of Succession in 1714 until the conquest by French revolutionary troops and the annexation to the French Republic in 1797.

- France (1797 – 1815) – France took over the Austrian Netherlands during the French Revolutionary Wars.

- Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815 – 1830) – After the defeat of Napoleon, Willem V, Prince of Orange, urged on by the powers who met at the Congress of Vienna, proclaimed the Netherlands a monarchy on March 16, 1815. The new United Kingdom of the Netherlands consisted of territories that had belonged to the former Dutch Republic, Austrian Netherlands, and Prince-Bishopric of Liège

********************

Credit – Door SMYRKINNE – Eigen werk, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16769142

The current Belgian royal family has used the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula for weddings and funerals but not for burials. All the monarchs, all the consorts, and some other members of the Belgian royal family have been buried at the neo-gothic Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of Laeken in Brussels, Belgium. The church was built in memory of Queen Louise-Marie, wife of Belgium’s first monarch King Leopold I. Since the reign of Albert I, King of the Belgians, most royal baptisms have been held at the Church of Saint Jacques-sur-Coudenberg in Brussels. Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld stood on the steps Church of Saint Jacques-sur-Coudenberg when he took the oath that made him Leopold I, the first King of the Belgians on July 21, 1831.

Above: Statues of Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint Gudula in the Cathedral of Saint Michael and Saint Gudula; Credit – Wikipedia

The patron saints of the church, Saint Michael and Saint Gudula, are also the patron saints of the City of Brussels. Saint Michael is the familiar Saint Michael the Archangel. A local female saint, Saint Gudula of Brabant, was born circa 646 in Brabant in present-day Belgium and died between 680 and 714. The cathedral stands on what was Treurenberg Hill in Brussels where there was a crossroads of two important old roads – Flanders to Cologne and Antwerp to Brussels. A chapel to St. Michael was built on Treurenberg Hill in the ninth century and was replaced by a Romanesque church in the eleventh century. In 1047, Lambert II, Count of Louvain and his wife Oda of Verdun founded a canon, a community of non-monastic clergy, in honor of Saint Gudula. Lambert arranged for the relics of St. Gudula to be transferred from another church in Brussels. From that time, the church became known as the Collegiate Church of St. Michael and St. Gudula.

In 1200, under Henri I, Duke of Brabant, the church was restored and enlarged. However, in 1226, Henri II, Duke of Brabant decided to build a new Gothic-style church. The choir was constructed between 1226 – 1276. The nave and transept date from the 14th and 16th centuries. The façade and the two towers were built from 1470 – 1485. The new church was completed in 1519. Several chapels were added in the 16th and 17th centuries. Restoration work was carried out in the 19th century and further restoration occurred from 1983 – 1999.

Detail of the painting Pastoral Instruction, showing the church with the north tower still incomplete, c. 1480; Credit – Wikipedia

On June 6, 1579, the church was pillaged by the Protestant Geuzen, a group of Calvinist Dutch nobles, and Saint Gudula’s relics were scattered and lost. In February 1962, the church was given cathedral status, and since then it has been the seat of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Mechelen-Brussels.

********************

Please note, the lists below may not be complete.

Royal Baptisms

The baptism of Louis-Philippe of Belgium, son of Leopold I, King of the Belgians; Credit – Wikipedia

- 1480: Margaret of Austria – daughter of Mary, Duchess of Burgundy in her own right (daughter of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy) and Maximilian of Austria, later Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

- 1498: Eleanor of Austria – daughter of Philip of Austria, Duke of Burgundy (son of Mary, Duchess of Burgundy and Maximilian of Austria, later Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor) and Juana I, Queen of Castile, Queen of Aragon

- 1833: Louis Philippe, Crown Prince of Belgium – son of Leopold I, King of the Belgians, died before his first birthday

Royal Weddings

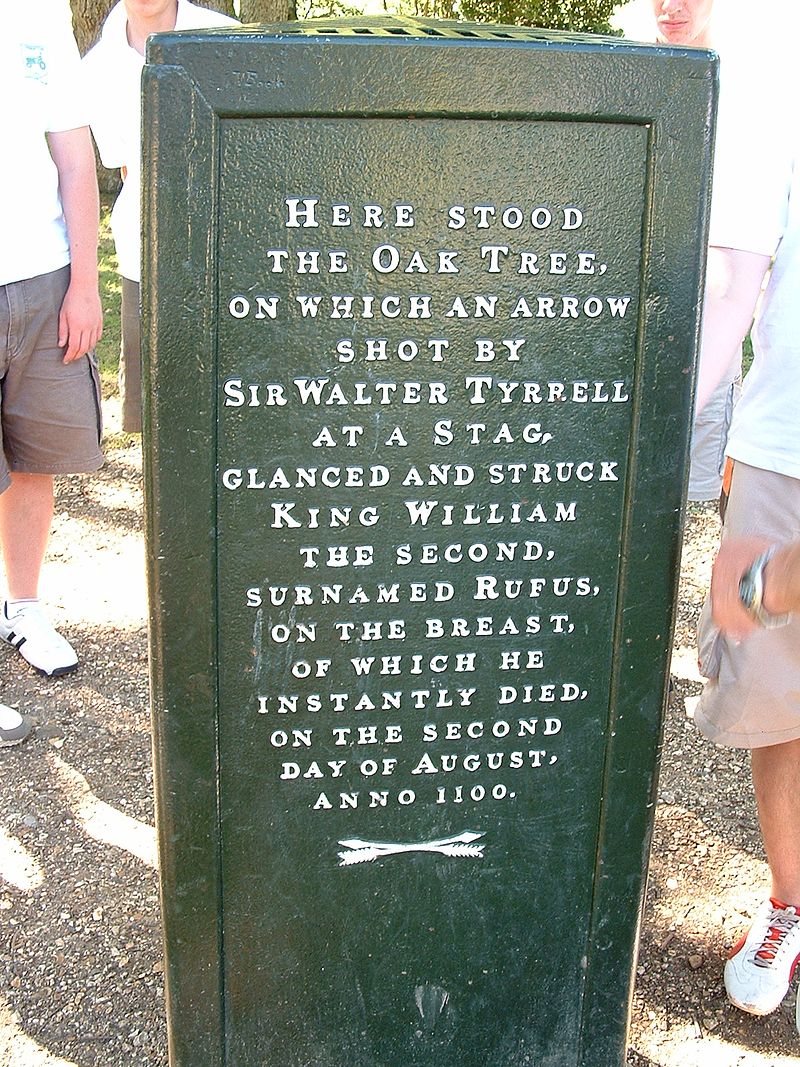

Wedding of the future Albert II, King of the Belgians and Paola Ruffo di Calabri

- August 22, 1853: Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant (the future Leopold II, King of the Belgians) and Marie-Henriette of Austria

- November 10, 1926: Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant (the future Leopold III, King of the Belgians) and Princess Astrid of Sweden – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of King Leopold III and Princess Astrid of Sweden

- July 2, 1959: Prince Albert, Prince of Liège (the future Albert II, King of the Belgians) and Paola Ruffo di Calabri – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of King Albert II and Paola Ruffo di Calabria

- December 15, 1960: Baudouin, King of the Belgians and Fabiola de Mora y Aragón – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of King Baudouin I and Fabiola de Mora y Aragón

- December 4, 1999: Prince Philippe, Duke of Brabant (the future Philippe, King of the Belgians) and Mathilde d’Udekem d’Acoz – Unofficial Royalty: Wedding of King Philippe and Mathilde d’Udekem d’Acoz

- April 12, 2003: Prince Laurent of Belgium and Claire Coombs

Royal Funerals

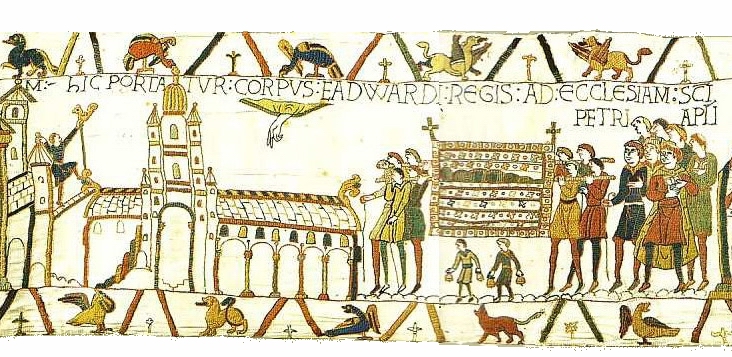

The royal families of Belgium and Luxembourg pray during the funeral mass for Baudouin, King of the Belgians. From left to right: Prince Laurent of Belgium, Prince Philippe of Belgium, Queen Paola of the Belgians, Baudouin’s brother King Albert II of the Belgians, Baudouin’s widow Queen Fabiola in white, Baudouin’s sister Grand Duchess Joséphine-Charlotte of Luxembourg, Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg, and Princess Astrid of Belgium

- 1312: Jean II, Duke of Brabant

- 1333: Margaret of England, Duchess of Brabant – wife of Jean II, Duke of Brabant, daughter of Edward I, King of England

- 1446: Catherine of France, Countess of Charolais – first wife of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, daughter of Charles VII, King of France

- 1595: Archduke Ernst of Austria – son of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor

- 1621: Albrecht VII, Archduke of Austria – Governor of the Spanish Netherlands

- 1745: Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria – Governor of the Austrian Netherlands, wife of Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine

- 1780: Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine – Governor of the Austrian Netherlands

- February 22, 1934: Albert I, King of Belgians – fell to his death in a mountain climbing accident

- September 3, 1935: Astrid, Queen of the Belgians – born Princess Astrid of Sweden, wife of Leopold III, King of the Belgians, killed in a car accident

- November 30, 1965: Elisabeth, Queen of the Belgians – born Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria, wife of Albert I, King of the Belgians

- August 7, 1993: Baudouin I, King of the Belgians

- December 12, 2014: Fabiola, Queen of the Belgians – born Fabiola de Mora y Aragón, wife of Baudouin I, King of the Belgians

Royal Burials

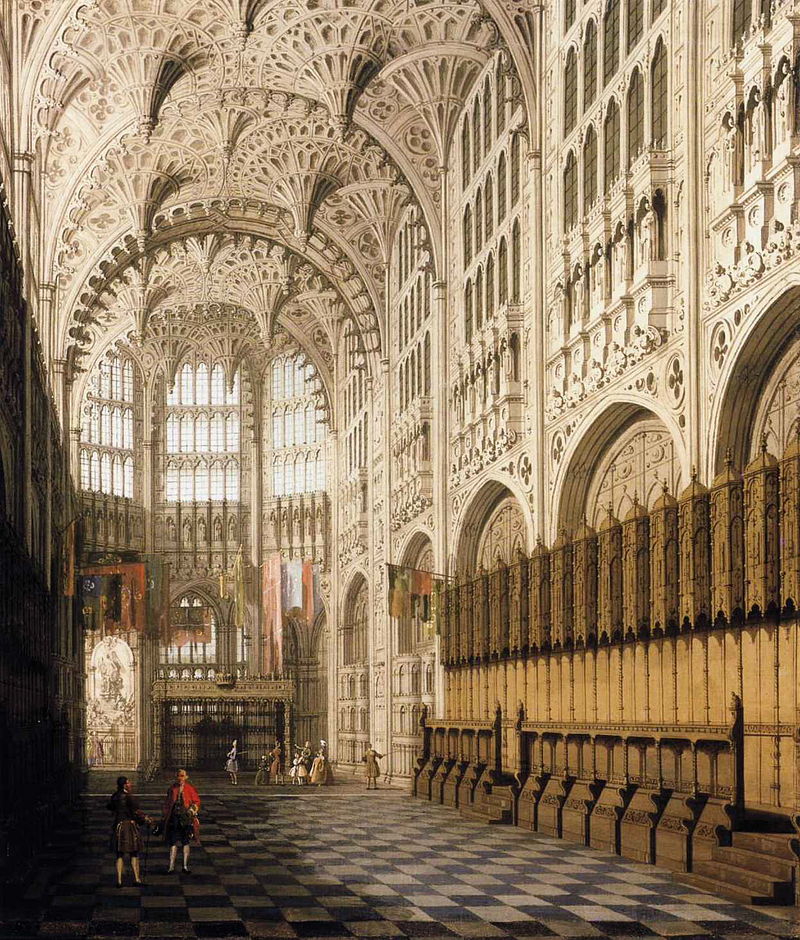

Tomb of Archduke Ernst of Austria; Credit – By PMRMaeyaert – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17308156

- 1312: Jean II, Duke of Brabant

- 1318: Margaret of England, Duchess of Brabant – wife of Jean II, Duke of Brabant, daughter of Edward I, King of England

- 1446: Catherine of France, Countess of Charolais – first wife of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, daughter of Charles VII, King of France

- 1595: Archduke Ernst of Austria – son of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor

- 1621: Albrecht VII, Archduke of Austria – Governor of the Spanish Netherlands

- 1650: Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain, Archduchess of Austria – Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, wife of Albrecht VII, Archduke of Austria, daughter of Felipe II, King of Spain (reinterred seventeen years after her death)

- 1780: Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine – Governor of the Austrian Netherlands

- 1834: Louis Philippe, Crown Prince of Belgium – infant son of Leopold I, King of the Belgians, died before his first birthday. In 1993, during the restoration of the Cathedral of Saint Michael and Saint Gudula, Crown Prince Louis Philippe’s remains were transferred to the Church of Our Lady of Laeken, the burial church of the Belgian royal family where they were buried in a side chapel of the crypt.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Cathedralisbruxellensis.be. 2021. Brussels Cathedral | Saint Michael and Saint Gudula Cathedral in Brussels. [online] Available at: <https://www.cathedralisbruxellensis.be/en/> [Accessed 17 July 2021].

- Commons.wikimedia.org. 2021. Category:Tombs in the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula – Wikimedia Commons. [online] Available at: <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Tombs_in_the_Cathedral_of_St._Michael_and_St._Gudula> [Accessed 17 July 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathedral_of_St._Michael_and_St._Gudula> [Accessed 17 July 2021].

- Findagrave.com. 2021. Memorials in Cathedral of Saint Michael and Saint Gudula – Find A Grave. [online] Available at: <https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/639544/memorial-search?page=1#sr-19231> [Accessed 17 July 2021].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. 2021. Cathédrale Saints-Michel-et-Gudule de Bruxelles — Wikipédia. [online] Available at: <https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cath%C3%A9drale_Saints-Michel-et-Gudule_de_Bruxelles> [Accessed 17 July 2021].

- Nl.wikipedia.org. 2021. Kathedraal van Sint-Michiel en Sint-Goedele – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathedraal_van_Sint-Michiel_en_Sint-Goedele> [Accessed 17 July 2021].