by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

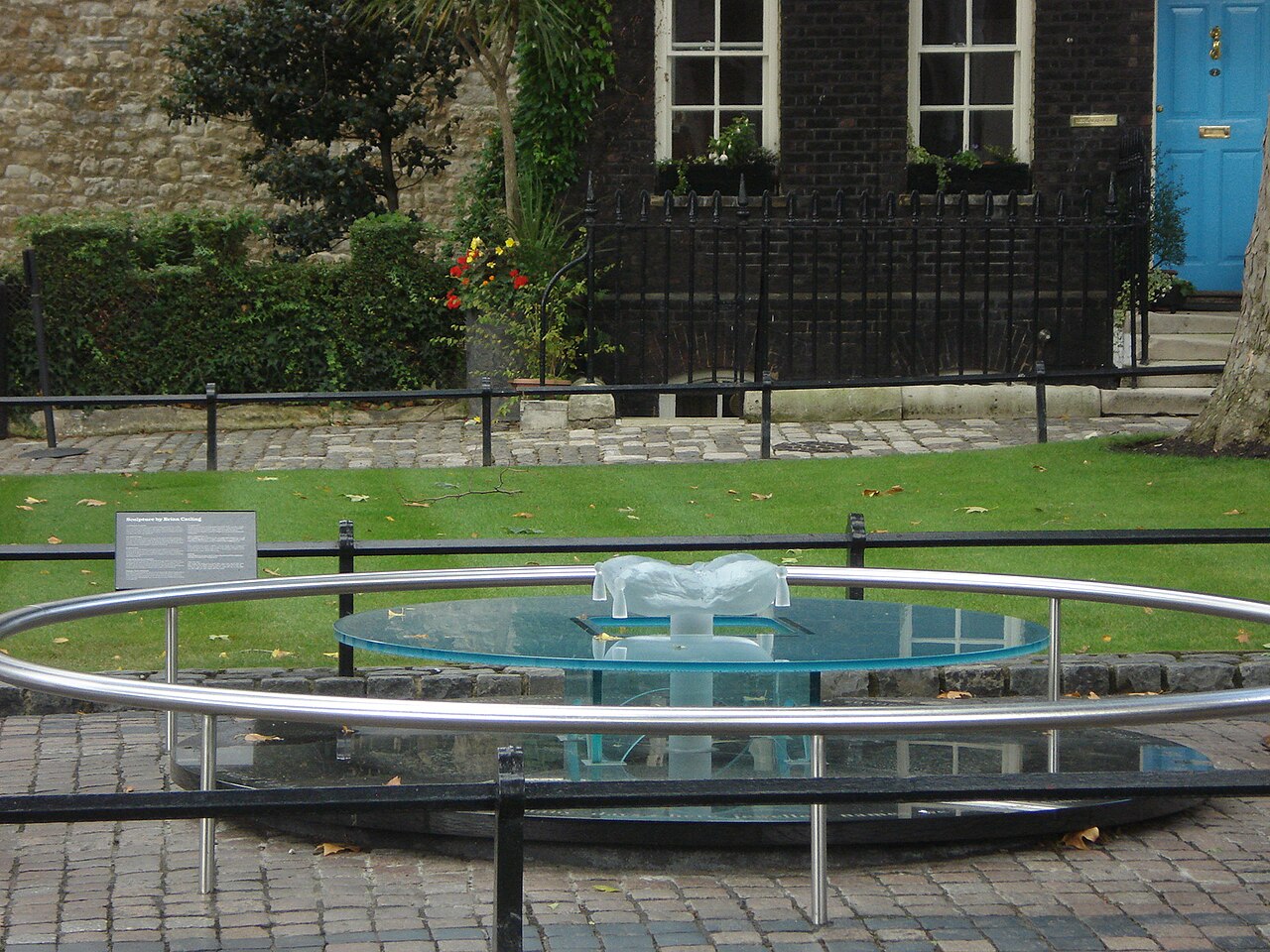

Model of Old St. Paul’s Cathedral; Credit – By Ben Sutherland – https://www.flickr.com/photos/bensutherland/7083572515, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51702266

- Oprah Book Clubs: Cathedral Floor Plan and Cathedral Building Terms

- Official Website: St. Paul’s Cathedral

Old St. Paul’s Cathedral stood on the site of the present St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, England until it was severely damaged in the Great Fire of London in 1666. There have been churches and religious communities on the site since Roman times. The first cathedral built on the site dedicated to St. Paul dates from 604. Historians think Old St. Paul’s Cathedral was the fourth church on the site. A major fire occurred in London in 1087, at the beginning of the reign of William II Rufus, King of England. The previous church was the most significant building to be destroyed in the 1087 fire. The fire also damaged the Palatine Tower, built by William I (the Conqueror), King of England on the banks of the River Fleet in London, so badly that the remains had to be pulled down. Part of the stone from the Palatine Tower was then used in the construction of Old St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Work on Old St. Paul’s Cathedral began in 1087 and construction was delayed by another fire in 1135. The cathedral was completed in 1240 and enlarged in 1256 – 1314, although it had been consecrated in 1300. In 1314, Old St. Paul’s Cathedral was the third-longest church in Europe at 586 feet/178 meters. The spire was completed in 1315 and, at 489 feet/149 meters, it was the tallest in Europe at that time. The walls of the cathedral were made of stone. However, the roof was mostly wood because stone would have been too heavy to support. The decision to use wood for the roof would lead to dire consequences in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

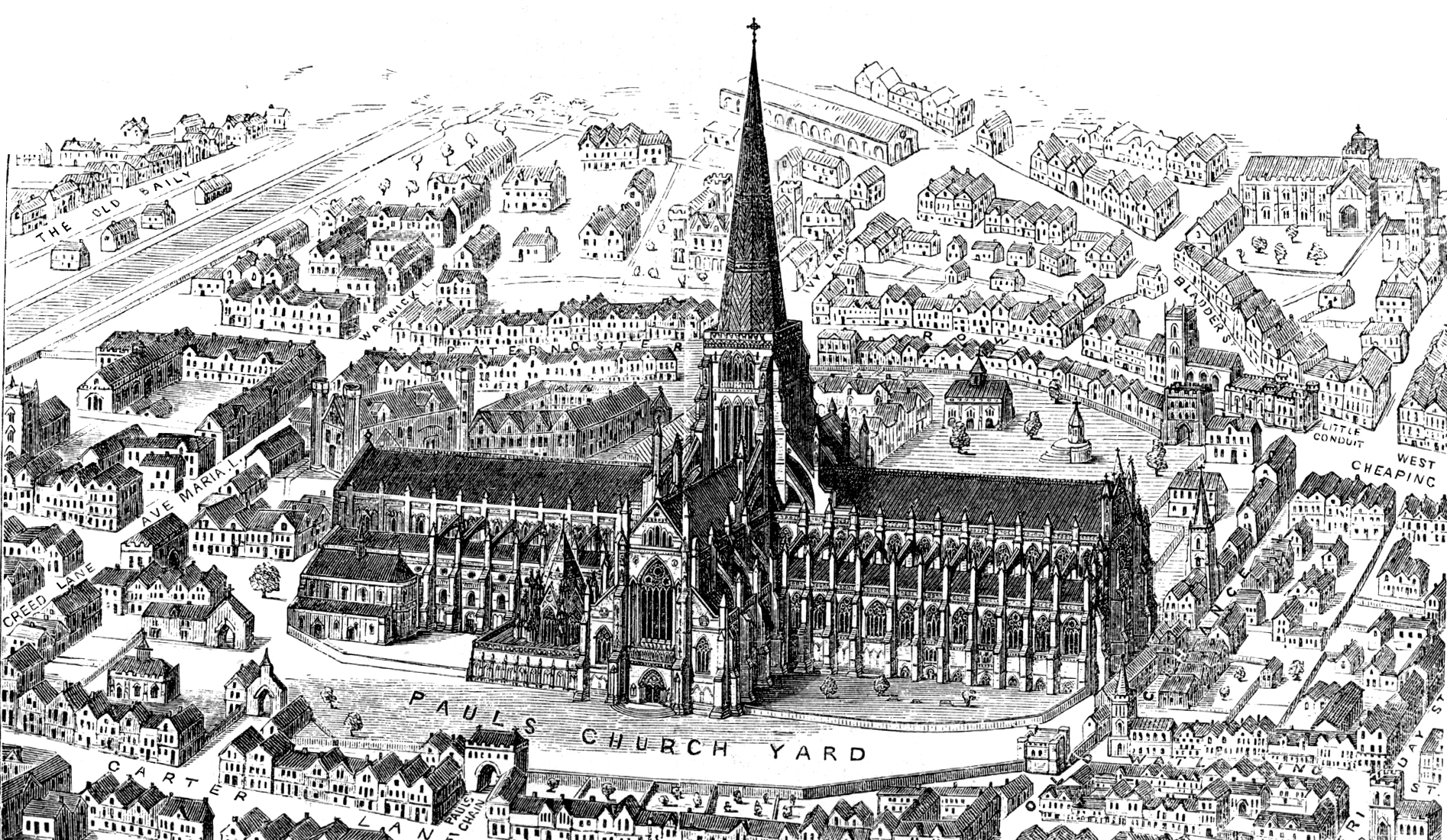

1916 engraving of Old St Paul’s as it appeared before the fire of 1561 in which the spire was destroyed; Credit – Wikipedia

By the 16th century, Old St. Paul’s Cathedral was deteriorating. In 1549, radical Protestant preachers incited a mob to destroy much of the cathedral’s interior. The spire caught fire in 1561 and crashed through the nave roof. The roof was repaired but the spire was never rebuilt. In 1621, King James I of England appointed architect Inigo Jones to restore the cathedral but the work stopped during the English Civil War and the Commonwealth of England. In 1660, after the restoration of the monarchy, King Charles II of England gave architect Sir Christopher Wren the job of continuing the restoration of the cathedral. That restoration was in progress when Old St. Paul’s Cathedral was severely damaged in the 1666 Great Fire of London. What remained of Old St. Paul’s Cathedral was demolished, and the present cathedral, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, was built on the site.

Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in flames; Credit – Wikipedia

Royal Events at Old St. Paul’s Cathedral

Richard II, King of England was deposed by his first cousin Henry of Bolingbroke who then reigned as Henry IV, King of England. Held in captivity at Pontefract Castle in Pontefract, West Yorkshire, England, Richard is thought to have starved to death and died on or around February 14, 1400. Although Henry IV has often been suspected of having Richard murdered, there is no substantial evidence to prove that claim. It can be positively said that Richard did not suffer a violent death. After his death, Richard’s body was put on public display for three days at the Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, both to prove to his supporters that he was truly dead and also to prove that he had not suffered a violent death. Whether Richard did indeed starve himself or whether that starvation was forced upon him is still up for speculation.

Richard II’s body is brought to Old St Paul’s Cathedral to let everyone see that he is dead – engraving from A Chronicle of England: B.C. 55 – A.D. 1485 by James William Edmund Doyle (1864); Credit – Wikipedia

English monarchs were often in attendance at the Old St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the court occasionally held sessions there. Arthur, Prince of Wales, son of King Henry VII of England, married Catharine of Aragon at Old St. Paul’s on November 14, 1501. Several kings, including Henry VI, and Henry VII, lay in state in Old St. Paul’s before their funerals at Westminster Abbey.

Royal Burials at Old St. Paul’s Cathedral

Commemoration of those who were buried or memorialized in Old St. Paul’s Cathedral but whose tombs or memorials have not survived; Credit – Wikipedia

Only the monument to poet John Donne survived the 1666 Great Fire of London. No other memorials or tombs of the many famous people buried at Old St. Paul’s Cathedral survived the fire. In 1913, an inscribed stone, set up on a wall in the crypt of the new St. Paul’s Cathedral, lists those known to have tombs or memorials lost in the Great Fire of London, including several royals listed below

- Saint Sæbbi, King of Essex, died 695

- Æthelred II, King of the English, died 1016

- Edward the Exile, son of Edmund II (Ironside), King of English, died 1057

- Blanche of Lancaster, Duchess of Lancaster, wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, died 1368

- John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, son of Edward III, King of England, died 1399

Tomb of John of Gaunt and his first wife Blanche of Lancaster, lost in the 1666 Great Fire of London; Credit – Wikipedia

Works Cited

- Britain Express. 2021. St. Paul’s Cathedral, London – early history. [online] Available at: <https://www.britainexpress.com/London/st-pauls.htm> [Accessed 4 April 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Old St Paul’s Cathedral – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_St_Paul%27s_Cathedral> [Accessed 4 April 2021].

- Es.wikipedia.org. 2021. Antigua catedral de San Pablo – Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. [online] Available at: <https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antigua_catedral_de_San_Pablo> [Accessed 4 April 2021].

- The Inside Page Ltd, 2004. St Paul’s Cathedral – Official Guide. London: Jerrold Publishing.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.