by Emily McMahon © Unofficial Royalty 2017

King Leopold III of the Belgians and Princess Astrid of Sweden; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant (the future King Leopold III of the Belgians) and Princess Astrid of Sweden were married in a civil ceremony in the throne room of the Royal Palace in Stockholm, Sweden on November 4, 1926, and in a religious ceremony on November 10, 1926, at the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula in Brussels, Belgium.

Leopold’s Early Life

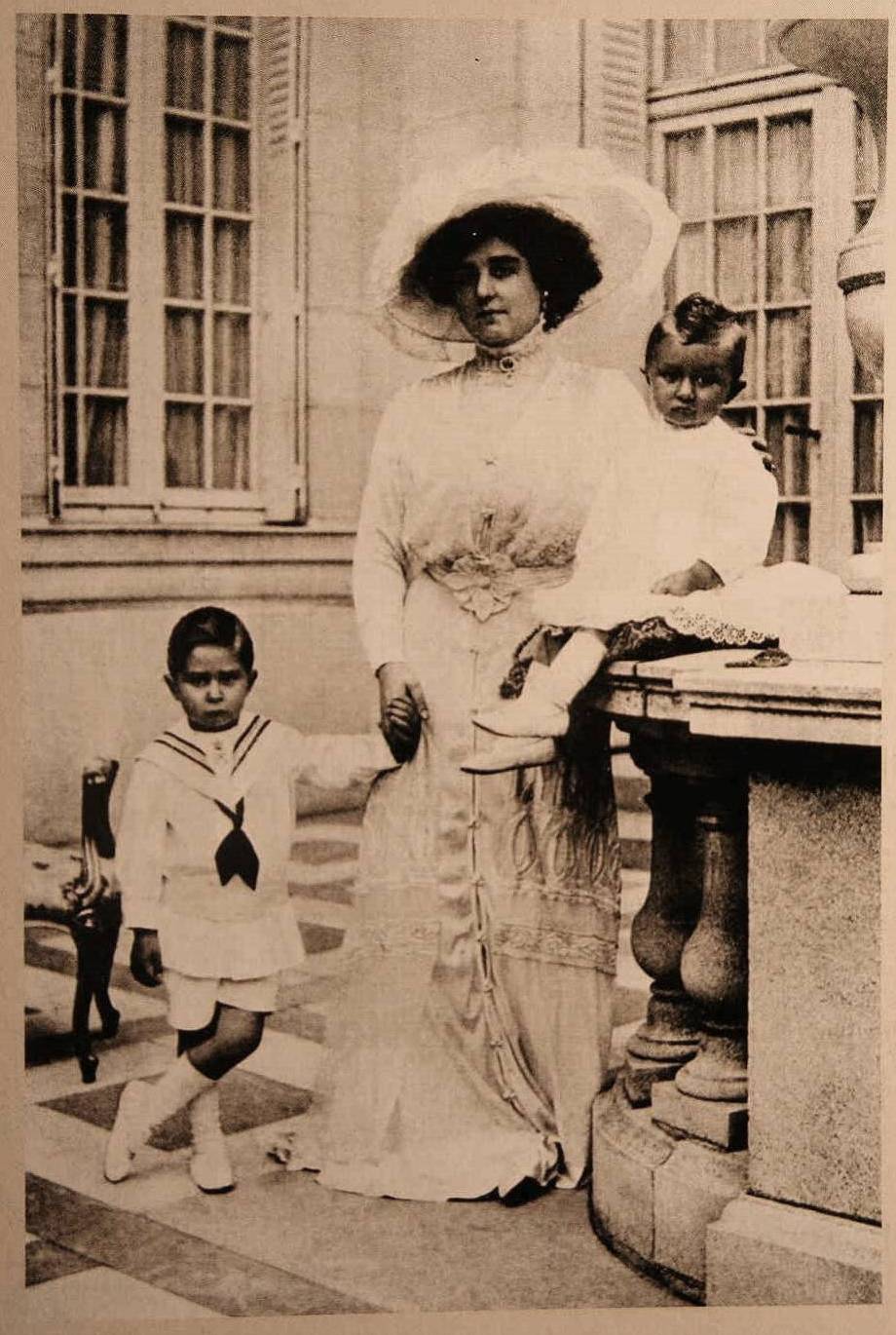

Left to right Leopold, his brother Charles, his mother Queen Elisabeth, and his sister Marie José;Credit – Wikipedia

Leopold was born in Brussels, Belgium on November 3, 1901, to the future Albert I, King of the Belgians and Elisabeth of Bavaria. Leopold had a younger brother Charles who later served as the Regent of Belgium. His younger sister Marie-Jose was briefly Queen of Italy after World War II. Leopold was educated in the United Kingdom at Eton College, in Belgium at Ecole Militare (the Belgian equivalent of Sandhurst), and later in the United States at St. Anthony Seminary in California.

The product of a happy marriage (particularly for a royal couple), Leopold had a contented, rather bohemian upbringing. Unlike his uncle and predecessor King Leopold II, Albert preferred a quieter, almost middle-class domestic life for his family. Albert and Elisabeth were well-educated and enthusiastic about developing a Belgian cultural scene. Elisabeth was particularly supportive of musicians. She was also an avid gardener and encouraged her son’s budding interest in botany. Albert was known to jump into haystacks with his children while on vacation in the Belgian countryside. Leopold was close to his father and shared with him a love of outdoor sports.

Following a short stay with his siblings in the United Kingdom, Leopold served as a private and later a sergeant in the 12th Belgian Regiment during World War I, particularly devastating to his home country. Leopold held the unique position of being the youngest known soldier to fight for Belgium during the war. He was fully enlisted by his father at the age of 13. The enlistment was not a ceremonial one. Leopold was treated as any other Belgian private during his service. The 12th Belgian Regiment was later named in honor of its most famous soldier.

Leopold thrived at sports during his school years. After he completed his education, Leopold maintained his physical regimen by swimming, riding, and, like his father, mountain climbing. He also enjoyed some of the typical pursuits of young royal men of the time, fast cars, airplanes, and photography. Leopold also had a very keen interest in boxing, later following well-known American boxers such as Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney.

After the war, Leopold served as a lieutenant in the Belgian Grenadiers. He also traveled extensively throughout Europe and Africa as the capstone of an education interrupted by the war. Leopold reportedly said to a friend that if had he not been born an heir to a kingdom, he would have become a sea captain and traveled the world.

During his young adulthood, Leopold continued to cultivate his interest in nature, particularly in tropical vegetation and animals. In 1925, Leopold made a long trip to the Congo, where he took extensive notes and collected several specimens of the flora and fauna he encountered. Leopold remained fascinated with botany and zoology throughout his life, keeping hothouses and apiaries at his various homes.

For more information about Leopold see:

Astrid’s Early Life

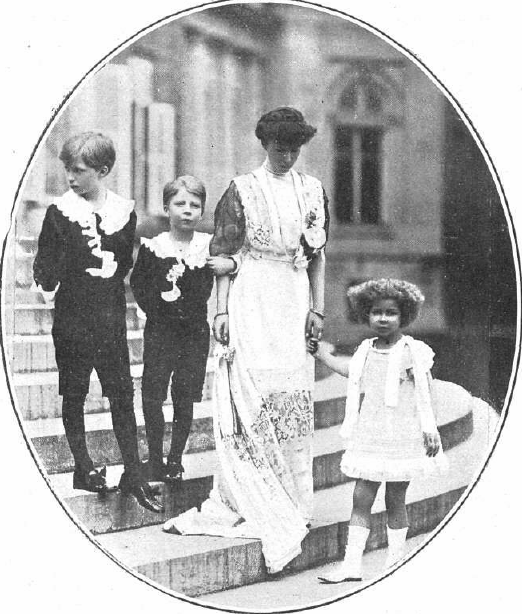

Left to right: Astrid’s sister Margareta, her mother Princess Ingeborg, her sister Märtha and Astrid; Photo Credit – By Municipal Archives of Trondheim – Flickr: H. K. H. Prinsessan Ingeborg med Prinsessorna Margareta, Märta och Astrid (1910), CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25766188

Astrid was born in Stockholm, Sweden on November 17, 1905, to Prince Carl, Duke of Västergötland, and Princess Ingeborg of Denmark. Astrid was the grandchild of both King Frederik VIII of Denmark and King Oscar II of Sweden. Astrid’s uncle was King Gustav V of Sweden, her father’s older brother. She had two older sisters, Margaretha, who married into the Danish royal family, and Märtha, who married the future King Olav V of Norway. Astrid’s only brother Carl was born in 1911. Astrid spent most of her childhood at Arvfurstens Palace in central Stockholm and at the family’s summer residence in Fridhem.

Although never academic, Astrid had a warm, friendly personality, social ease, and considerable charm. She collected Swedish folk art and was an expert in the regional variations of needlework. Astrid also enjoyed the outdoors and sports – swimming, skiing, climbing, horseback riding, and golf – loves she later shared with her husband. As she was not a direct descendant of the Swedish king (Gustav V), Astrid and her sisters enjoyed more freedom and the benefits of a less formal schedule. The girls were occasionally seen shopping unaccompanied on the streets of Stockholm.

Like many princesses of the time, Astrid was encouraged to undertake works of public service in preparation for a life devoted to charitable causes. Astrid worked for a time at a Stockholm orphanage, caring for infants. She also completed a home economics course at a Swedish school dedicated to preparing women for domestic lives. During that time, Astrid developed a flair for cooking and would often try out new recipes on her family.

For more information about Astrid see:

The Engagement

Astrid and Leopold’s engagement photo; Credit – Wikipedia

Leopold came of age during World War I, a watershed and devastating time for much of Europe. Several Catholic princesses who may have been available before the war were now left destitute or on the side of Belgium’s former enemies. Many, such as the daughters of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, were simply too young for Leopold. Albert and Elisabeth realized that a suitable bride would likely need to come from an area less affected by the Great War.

Knowing her son’s love of travel, Elisabeth began organizing trips to various European countries to meet eligible princesses. There was some interest in the two eldest daughters of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and a Romanian princess (likely the future Maria of Yugoslavia or her sister Ileana), but despite trips to these areas, no engagement came about.

Astrid and Leopold first met during Leopold’s trip to Scandinavia in the fall of 1925. Leopold and Elisabeth traveled under the name “de Rethy” to avoid public speculation about the reason for the trip. During the first visit, Leopold and Astrid chatted in their common language (English) and developed an attachment to one another immediately.

Following this initial meeting, the residents of Fridhem began to notice a plainly dressed young man arrive for frequent visits. He traveled by third-class carriage and carried his own luggage. Some assumed that the man, dignified, but otherwise unassuming, was a new butler for Astrid’s father, as he entered Prince Carl’s home via the rear entrance. The young man was actually Leopold continuing to visit Astrid semi-incognito.

As the Great War had left a shortage of Protestant, non-German princesses eligible for marriage, Astrid and her sisters became unexpectedly popular potential brides for the royalty of the time. At the beginning of 1926, Astrid was repeatedly linked to Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) as his likely bride. As late as August 1926, Astrid was romantically tied to the future King Olav V of Norway, who later became her brother-in-law. Meanwhile, Leopold periodically visited Astrid privately in Sweden. The couple was exchanging letters while they were separated.

After the announcement of their engagement, the international press amusingly remarked on how Astrid’s culinary skills supposedly impressed Leopold. At a dinner during one of his visits to Sweden, Leopold was said to have been bowled over by an endive salad of Astrid’s own recipe and creation. At least one newspaper printed a handwritten copy of the recipe with an English translation for eager girls to win over their own princes.

The two met again publicly at the christening of Prince Michael of Bourbon-Parma in the middle of 1926. On September 21, 1926, shortly after the christening, Astrid and Leopold announced their engagement. Whereas royal marriages were often arranged purely for convenience or political gain, this engagement seemed different. Not long after the announcement Astrid and Leopold were seen periodically in Stockholm holding hands.

Albert and Elisabeth were delighted at their son’s choice of a bride. They found Astrid quite pretty, yet natural and unassuming. Elisabeth remarked of Astrid, “I might not, even had I tried, have succeeded in finding for my son an ideal bride, but Leopold has done more, he has found for me an ideal daughter-in-law!” An amused (and short-statured) Elisabeth also remarked that Astrid was tall enough to reach Leopold’s eyes. Albert declared this engagement, “a love match … a marriage of inclination,” decided entirely by Leopold and Astrid and not solely for political gain.

King Gustav V held a celebratory dinner in honor of his niece and her new fiancé the night of the announcement. Gustav toasted the couple among members of both families, the Belgian ministry, and the Swedish cabinet.

Wedding Preparations

At the time of the engagement, both countries had sizable socialist populations. The fathers of Astrid and Leopold were concerned about the impact of criticism about the wedding from socialists. Carl selected Stockholm’s socialist mayor Carl Lindenhagen to officiate the civil ceremony despite Lindenhagen’s previous record of calling for the dissolution of the monarchy.

Previous royal weddings in Belgium had been held with excessive formality, particularly with the official arrival of the bride. Albert was careful to note that Astrid’s arrival in Belgium would be marked by as little ceremony as possible. However, the Belgian public was keenly interested in their soon-to-be princess. Wax figures and photographs of Astrid began appearing in shops soon after the engagement was announced. News footage of Astrid was also included before feature films in theaters. Seats on balconies along wedding parade routes in Antwerp (where Astrid would arrive in Belgium) and Brussels sold for several hundred francs.

Unusual for a royal bride at the time, Astrid initially kept her Lutheran faith after marrying Leopold. A dispensation was sought (and granted) to Leopold by Pope Pius XI for marrying a non-Catholic. Astrid agreed that any children born of the marriage would be raised Catholic. Leopold urged Astrid to adopt the Catholic faith only if she felt an individual desire to do so. Astrid later converted three years after the marriage.

The Belgians and Swedes extended the good cheer surrounding the events to the prison inmates of both countries. Convicts had their sentences reduced or were released, based on their behavior during incarceration, their crimes, and the length of their sentences.

Leopold left Belgium for Sweden on October 30, 1926, in preparation for the civil wedding scheduled for November 4, 1926. He stayed at the home of his in-laws in order to spend as much time with Astrid as possible. In the days leading up to the wedding, he and his fiancée were seen periodically walking around Stockholm, arm in arm.

The remainder of the Belgian royal family arrived in Stockholm on November 3, 1926. A crowd gathered to welcome the family as Leopold met his parents and siblings outside the city. Crown Prince Olav of Norway, Prince Axel of Denmark, and Princess Margaretha of Denmark joined the spectators in street clothes and went unrecognized as royalty. Meanwhile, Astrid tried on her wedding dress and baked a chocolate cake for Leopold’s 25th birthday celebrations. Lean reindeer steaks, a Swedish delicacy, were served to the receptive Belgian guests. Following the dinner, the couple and several members of the entourage attended an opera performance.

The Civil Wedding in Sweden

The Royal Palace in Stockholm, Sweden where the civil wedding was held; Credit – Wikipedia

The civil ceremony was held in the throne room of the Swedish Royal Palace in Stockholm on November 4, 1926. King Gustav V of Sweden and Queen Elisabeth of Belgium led the procession of royal guests into the Throne Room, followed by King Haakon VII of Norway, King Christian X and Queen Alexandrine of Denmark, Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg, and several minor princes and princesses. Astrid and Leopold followed, holding hands, to the strains of the Swedish processional, “The Peasant’s Wedding.”

The ceremony was officiated by Carl Lindhagen, the mayor of Stockholm and a socialist. The wedding marked the first time a couple had been married at the Swedish Royal Palace by anyone other than a member of the clergy. For his part, Mr. Lindhagen said he was happy to marry a couple who appeared to be so in love. The groom presented his bride with a simple gold band as a wedding ring. Astrid and Leopold were reported to have smiled throughout the ceremony. At the close of the service, the orchestra played the Belgian and Swedish national anthems.

The light snow that fell on the day of the wedding was seen as a sign of good luck, as per an old Swedish proverb that foretold of a happy marriage if snow fell on the bride’s myrtle crown. Hundreds of Swedish and Belgian flags decorated the streets of the capital city

A 21-gun salute announced the marriage to the Swedish public, followed by a dinner given by Gustav V to the guests. Despite an unseasonably cold evening, Astrid and Leopold left the palace by horse-drawn carriage through illuminated Stockholm.

As they had not yet been religiously married, Astrid and Leopold were allowed only four hours alone after the civil wedding. The couple then departed separately with their families – Astrid to Malmo and Leopold to Gothenburg.

The Religious Wedding in Belgium

St. Michael and St. Gudula Cathedral in Brussels, Belgium; Photo Credit – By I, Luc Viatour, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4789498

The religious wedding was held on November 10, 1926, at 11:15 AM in the 13th-century St. Michael and St. Gudula Cathedral in Brussels, Belgium. The cathedral was reportedly full an hour before the scheduled ceremony with an estimated 9,000 guests. The weather was reported to be bright and mild for a November day. Leopold and Astrid set off from the royal palace just before 11:00 AM on a street lined with soldiers, ordinary citizens, and decorations. The remainder of the royal entourage followed, all in open carriages.

The streets of Brussels had not seen such large crowds since Armistice Day in 1918. So enthusiastic were the 200,000-300,000 spectators gathered to see the newly married couple that several injuries were reported due to trampling and crowding. As in Antwerp, Belgian and Swedish flags were displayed on the streets of Brussels. An estimated 15,000 soldiers joined the crowds, many World War I veterans who gathered specifically for the occasion.

Female guests were instructed not to wear black (the color of mourning) or white (as it was thought to be distracting), but instead wore mostly pastel dresses popular at the time. Most covered their heads in lace or, in the case of wealthier guests, donned tiaras.

The international press again took delight in reporting Astrid and Leopold’s affections for one another, declaring the marriage a true love match and lamenting the long distance that had separated the two during their courtship. The ceremony was also broadcast on the radio, a first for Belgian royal weddings.

The ceremony began at 11:30 AM, later than planned due to slow traffic. As the couple entered the church, a 21-gun salute sounded. The cheering was apparently so loud that the salute could barely be heard.

Bells were rung throughout the wedding both inside and outside of the church. The religious service, lasting about forty minutes, was officiated by Archbishop Van Roey, a cleric who had originally declined to participate due to the differences in religion between Leopold and Astrid. No Nuptial Mass was performed as Astrid was not a practicing Catholic. A choir of sixty men and 100 children sang songs of celebration during the processional and recessional. During the ceremony, Leopold gave Astrid a large diamond ring to compliment her plain gold wedding band presented at the civil wedding.

Upon leaving the church, the new couple waved at the crowds before passing under a tunnel of swords held up by Leopold’s former classmates at the Ecole Militaire. Following a carriage processional through Brussels, Leopold and Astrid appeared on the palace balcony again waving at the crowds.

A reception from 3:00 PM-5:00 PM followed the religious service with 3,000 guests, mostly other royals and members of the wedding party. Shortly after the reception, Leopold and Astrid left by car for an undisclosed honeymoon location.

The wedding celebrations had hardly ended before speculation began on another Belgian-Scandinavian union – Olav of Norway and Leopold’s sister Marie-Jose.

Wedding Attire

Astrid wore different dresses for her two wedding ceremonies, both of satin. The Swedish dress featured a scooped neckline with scalloped layers of lace-trimmed satin at the hem. At the Belgian wedding, Astrid wore a cream wrap dress with sprigs of lilies of the valley at her waist. The train was trimmed with embroidered flowers and seed pearls. The color was reported to be “very becoming” to the dark-haired Astrid. The skirt of her dress featured more Brussels lace, with a train carried by four pages dressed in white. Astrid carried a bouquet of lilies of the valley and orchids.

Astrid’s veil was made of Brussels, fitting for her future role as Queen of the Belgians, which had previously been worn by her mother and older sister Margaretha. During the Swedish ceremony, Astrid wore the crown of myrtle in her hair, typical for Swedish brides. While Astrid wore the same veil for both weddings, the wearing of the Swedish myrtle crown necessitated a slightly different style for the veil. Astrid and her bridesmaids wore their hair in short, shingled styles. The bridesmaids wore sleeveless apricot-colored dresses of crepe georgette with hems that fell just below the knees.

Leopold wore the khaki field uniform of the Belgian Grenadiers. He was photographed in this uniform in many official pictures. However, Leopold’s attire differed slightly by the orders worn at the Swedish and Belgian ceremonies. At the Swedish civil wedding, Leopold wore the Order of the Seraphim, the Order of Leopold, and the Order of Leopold II. In addition to the first three, Leopold included the Order of the Crown, the Order of the African Star, and the Royal Order of the Lion at the religious wedding in Belgium.

The Wedding Party

Astrid and Leopold chose a mix of royal attendants (all were also family members of the couple) and their non-royal friends. Aside from Astrid and Leopold, there were four future monarchs and consorts serving as bridesmaids or groomsmen.

Astrid’s bridesmaids were Marie-Jose of Belgium, Leopold’s sister and future queen of Italy; Martha of Sweden, sister of Astrid and future Crown Princess of Norway; Feodora of Denmark, daughter of Prince Harald of Denmark and a cousin of the bride; and Ingrid of Sweden, another cousin of the bride and future Queen of Denmark and mother of Queen Margrethe II. Four of Astrid’s non-royal friends also served as bridesmaids: Alfhild Ekelund, Anne Marie von Essen, Margareta Stähl, and Anna Adelswärd. The bridesmaids traveled with Astrid from Malmo to Antwerp.

Leopold’s supporters were Prince Charles of Belgium, the groom’s younger brother; Prince Carl of Sweden, brother of the bride; Crown Prince Olav of Norway, a cousin of the bride; Prince Gustav Adolf of Sweden, a cousin of the bride; Count Folke Bernadotte, another of Astrid’s cousins; Count Claes Sparre, Baron Sigvard Beck-Friis, Baron Carl Strömfelt, all friends of Leopold.

Wedding Guests

Sweden hosted more than 1,200 at the civil wedding, while more than 3,000 attended the Belgian service. The guests at both events included the following royalty and dignitaries:

- Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

- King Albert I and Queen Elisabeth of Belgium

- Prince Carl and Princess Ingeborg of Sweden

- Princess Carl, Duke of Ostergotland

- Princess Märtha of Sweden

- King Gustav V and Queen Victoria of Sweden

- King Christian X and Queen Alexandrine of Denmark

- King Haakon VII and Queen Maud of Norway

- Olav, Crown Prince of Norway

- Crown Prince Gustav Adolf and Crown Princess Louise of Sweden

- Prince Gustav Adolf of Sweden, Duke of Västerbotten

- Prince Sigvard of Sweden, Duke of Uppland

- Princess Ingrid of Sweden

- Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg and Prince Felix of Bourbon-Parma

- Prince Knud and Princess Caroline-Mathilde of Denmark

- Prince Harald and Princess Helena of Denmark

- Princess Thyra of Denmark

- Prince Axel and Princess Margaretha of Denmark

- Robert Woods Bliss, U.S. Envoy to Sweden, and his wife, Mildred Barnes Bliss

- Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma

- Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma

- Prince Rene of Bourbon-Parma

- Count Carl de Wisborg

- Count Folke de Wisborg

The Honeymoon

Ciergnon Castle; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Leopold and Astrid began their honeymoon with a brief stay at Castle Ciergnon, a secluded royal property in a heavily wooded area in Namur, Belgium. Rumors had circulated that the couple was on their way to Switzerland and Cairo. These rumors may have been fabricated to allow the newlyweds some privacy. Leopold and Astrid the traveled through France via Paris to the Riviera. Outside Paris, the two stopped and toured around Montmartre, a former artists’ colony. The couple was known to be staying at a hotel in Menton (near the Italian border) in mid-December under the names of Monsieur and Madame Losange. Unrecognized in southern France, the couple visited tourist sites as any other honeymooning couple. Locals noticed the two taking several long walks together along the countryside.

Leopold and Astrid had three children:

- Princess Josephine-Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg (1927-2005), married Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg, had five children, Grand Ducal Family of Luxembourg descends from this marriage

- Baudouin, King of the Belgians (1930-1993), married Fabiola de Mora y Aragón, no children

- Albert II, King of the Belgians (born 1934), married Paola Ruffo di Calabria, had three children, Belgian Royal Family descends from this marriage

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.