by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

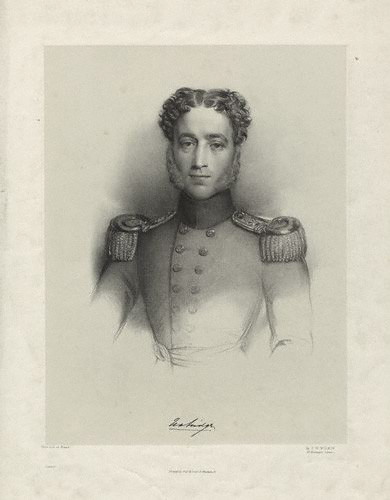

John Brown, circa 1860s; Credit – Wikipedia

John Brown served Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom as a ghillie at Balmoral (Scottish outdoor servant) from 1849 – 1861 and a personal attendant from 1861 – 1883.

Born on December 8, 1826, in Crathie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, John Brown was the second of eleven children of Scottish tenant farmer John Brown and his wife Margaret Leys. In 1842, Brown started work as a farmhand and eventually became a stable boy at Balmoral. In Scotland, outdoor servants were called ghillies.

At that time, Balmoral, owned by the Earl Fife, was leased to Sir Robert Gordon, a younger brother of George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, who made major alterations to the original castle at Balmoral. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert decided they wanted a home in Scotland. When Sir Robert died in 1847, an arrangement was made for Prince Albert to acquire the remaining part of the lease on Balmoral, together with its furniture and staff, sight unseen.

The old Balmoral Castle; Credit – Wikipedia

Renovations were considered, but by that time, negotiations were underway for Victoria and Albert to purchase Balmoral. In June 1852, the sale was complete with Prince Albert purchasing Balmoral for £32,000. Soon, Balmoral was too small for Victoria and Albert’s growing family, the staff, visiting friends, and official visitors. Construction on a new castle began during the summer of 1853. During the construction, the original castle could still be used. The new castle was completed in 1856, and the old castle was subsequently demolished.

The new Balmoral Castle; Photo Credit – By Stuart Yeates from Oxford, UK – Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=728182

Queen Victoria’s diary first mentions John Brown on September 8, 1849. She described a trip to Dhu Loch with ghillie John Brown, among others, accompanying her. From around 1851, John Brown became a permanent ghillie at Balmoral, often acting on behalf of Prince Albert, being responsible for the safety of Queen Victoria, or performing various outdoor tasks. Prince Albert enjoyed spending time with Brown and allowed him freedoms granted only to a very trusted servant. Three of Brown’s siblings also entered royal service. His brother Archibald Anderson “Archie” Brown, fifteen years younger than John, eventually became the personal valet of Victoria’s youngest son, Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany.

Princess Alice, Prince Leopold, Princess Louise, John Brown, and Princess Helena at Balmoral in 1860; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Albert’s untimely death in 1861 was a shock from which Queen Victoria never fully recovered. In 1864, Victoria’s personal physician Sir William Jenner ordered that she ride all winter. Victoria refused to be accompanied by a stranger, so John Brown was summoned to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight with Victoria’s Highland pony. His duties soon encompassed more than leading a horse. Brown became known as “the Queen’s Highland Servant” and took his orders exclusively from the Queen. Victoria called him “the perfection of a servant for he thinks of everything.”

Queen Victoria on ‘Fyvie’ with John Brown at Balmoral, 1863; Credit – Wikipedia

From then on, until his death nearly twenty years later, Brown was never far from Victoria’s side. There were rumors of a romance and a secret marriage, and Victoria was called Mrs. Brown. Brown treated the queen in a rough and familiar but kind manner, which she relished. In return, Brown was allowed many privileges, infuriating Victoria’s family. Victoria gave him gifts and created two medals for him:

- Victoria Devoted Service Medal, a gold medal inscribed “To John Brown, Esq., in recognition of his presence of mind and devotion at Buckingham Palace, February 29, 1872.”

- Faithful Servant Medal, a silver medal with bars denoting ten additional years of service.

John Brown took it upon himself the task of bringing bad news to the queen. It was Brown who brought Victoria the news that her daughter Alice had died on the same date as Albert’s death, seventeen years later. Victoria also sent him to inquire about the sick and dying. His presence was always a sign of the special and personal sympathy of Queen Victoria.

John Brown at Frogmore House, Home Park, Windsor by Carl Rudolph Sohn, 1883; Credit – Wikipedia

In March 1883, John Brown worked seven-day weeks despite having fever and chills. On March 27, 1883, at Windsor Castle, 56-year-old John Brown fell into a coma and died. The cause of death was erysipelas, a streptococcal skin infection. Queen Victoria wrote in her diary that she was “terribly moved by the loss that robs me of a person who has served me with so much devotion and loyalty and has done so much for my personal well-being. With him, I lose not only one Servant, but a real friend. ”

John Brown was buried in the cemetery at Crathie Kirk near Balmoral, next to his parents and some of his siblings. The inscription on his gravestone shows the affection between him and Queen Victoria:

“This stone is erected in affectionate and grateful remembrance of John Brown the devoted and faithful personal attendant and beloved friend of Queen Victoria in whose service he had been for 34 years.

Born at Crathienaird 8th Decr. 1826 died at Windsor Castle 27th March 1883.

That Friend on whose fidelity you count/that Friend given to you by circumstances/over which you have no control/was God’s own gift.

Well done good and faithful servant/Thou hast been faithful over a few things,/I will make thee ruler over many things/Enter through into the joy of the Lord.”

John Brown’s grave; Photo Credit – www.findagrave.com

Queen Victoria ordered that Brown’s room in Windsor Castle, where he had died, be left as it was during his lifetime, much like she had done with the room where Prince Albert had died. The Queen also commissioned a statue of John Brown from Sir Joseph Boehm to be set up at Balmoral. The Times published an obituary of Brown, which Queen Victoria had written herself. Victoria requested that upon her death, a lock of John Brown’s hair, a photo of him, and his mother’s wedding ring were to be placed in her coffin. Her physician Sir James Reid did as she requested without the knowledge of her family.

Statue of John Brown, sculpted by Sir Joseph Boehm at Balmoral; Credit – Wikipedia

Recommended Book – Serving Queen Victoria: Life in the Royal Household by Kate Hubbard

Works Cited

- Baird, Julia. Victoria The Queen. Random House, 2016.

- “Balmoral Castle”. En.Wikipedia.Org, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balmoral_Castle. Accessed 29 May 2018.

- Erickson, Carolly. Her Little Majesty: The Life of Queen Victoria.Simon and Schuster, 1997.

- Hubbard, Kate. Serving Victoria: Life In The Royal Household. Harper Collins Publishers, 2012.

- “John Brown (Diener)”. De.Wikipedia.Org, 2018, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown_(Diener). Accessed 29 May 2018.

- “John Brown (Servant)”. En.Wikipedia.Org, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown_(servant). Accessed 29 May 2018.

- Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. Cassell, 1998.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.