by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Edward, Prince of Wales as Knight of the Order of the Garter, illustration from the Bruges Garter Book 1453; Credit -Wikipedia

Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales was born at Woodstock Palace near Oxford in Oxfordshire, England on June 15, 1330. He was the eldest of the fourteen children of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Today, Edward of Woodstock is commonly referred to as “The Black Prince” although he was not called that in his lifetime. The first appearance of the reference occurred more than 150 years after his death. It may refer to Edward’s black shield, and/or his black armor or his brutal reputation, particularly towards the French in Aquitaine.

Edward of Woodstock was one of the seven Princes of Wales who never became King. The others are:

- Edward of Westminster, predeceased his father King Henry VI who was later deposed

- Edward of Middleham, predeceased his father King Richard III, two years later his father lost his crown and his life at the Battle of Bosworth Field

- Arthur Tudor, predeceased his father King Henry VII

- Henry Frederick Stuart, predeceased his father King James I

- James Francis Edward Stuart, his father King James II was deposed

- Frederick Louis, predeceased his father King George II

Edward had thirteen siblings:

- Isabella of England (1332 – 1379) married Enguerrand VII de Coucy, 1st Earl of Bedford, had issue

- Joan of England (1333/1334/1335 – 1348), died of the plague on the way to marry Pedro of Castile

- William of Hatfield (born and died 1337)

- Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence (1338 – 1368), married (1) Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster, had issue (2) Violante Visconti, no issue

- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (1340 – 1399), married (1) Blanche of Lancaster, had issue including King Henry IV of England (2) Infanta Constance of Castile, had issue (3) Katherine Swynford (formerly his mistress), had issue

- Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York (1341 – 1402), married (1) Infanta Isabella of Castile, had issue (2) Joan Holland, no issue

- Blanche of the Tower (born and died March 1342)

- Mary of Waltham (1344 – 1362), married John V, Duke of Brittany, no issue

- Margaret of Windsor, Countess of Pembroke (1346 – 1361), married John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, no issue

- Thomas of Windsor (1347 – 1348), died of the plague

- William of Windsor (born and died 1348), died of the plague

- Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester (1355 – 1397), married Eleanor de Bohun, had issue

In 1333, three-year-old Edward was created Earl of Chester and four years later, he was created Duke of Cornwall, the first creation of a dukedom in England. In 1343, he was created Prince of Wales. Marriage negotiations for a bride for Edward started when he was seven years old. His father’s first choice was a French princess, hoping that such a marriage would break up France and Scotland’s alliance, but nothing came of this possibility. Likewise, nothing came of negotiations with King Afonso IV of Portugal or John III, Duke of Brabant for the hands of their daughters.

Queen Philippa chose her almoner, philosopher Walter Burley, as Edward’s tutor. Edward was educated with a small group of companions. One of these companions, Simon de Burley, a relative of Walter Burley, became Edward’s lifelong friend and was later trusted with the education of Edward’s son, the future King Richard II. Edward’s knightly and military training was conducted by Walter Manny, 1st Baron Manny. Manny taught Edward the code of chivalry and the art of jousting. Edward participated in small tournaments and served as a page to his father at large tournaments.

Battle of Crécy from an illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles; Credit – Wikipedia

Best known for his military career in the Hundred Years War, Edward accompanied his father to France in the summer of 1346, participating in the Battle of Crécy, his first major battle, on August 26, 1346, where the English had a decisive victory. 16-year-old Edward, Prince of Wales commanded the vanguard with John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford, Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick, and Sir John Chandos. Edward was one of the 25 founding knights (the second knight after his father King Edward III) of the Order of the Garter in 1348. On September 19, 1356, Edward distinguished himself by winning a great victory at the Battle of Poitiers, taking King John II of France prisoner. Edward served as Lieutenant of Aquitaine from 1355 – 1372 and was created Prince of Aquitaine in 1362.

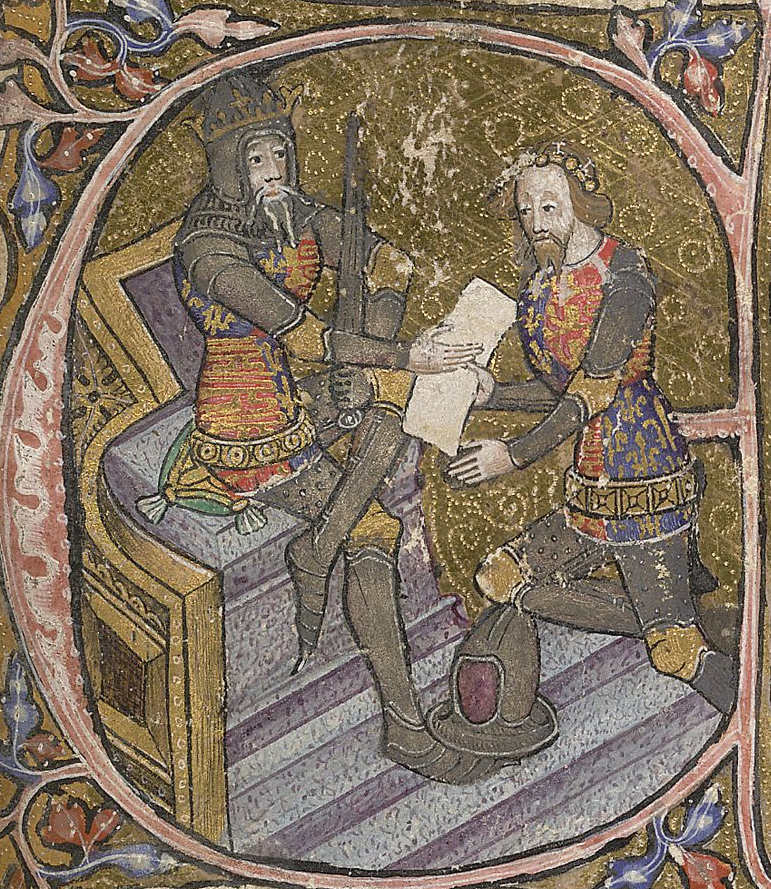

Edward, the Black Prince, is granted Aquitaine by his father King Edward III; Credit – Wikipedia

Edward married Joan, 4th Countess of Kent, his father’s first cousin, on October 10, 1361, at Windsor Castle. Joan was the daughter and heiress of Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent, the younger son of King Edward I of England by his second wife Margaret of France. In 1362, Edward was invested as Prince of Aquitaine, a region of France that belonged to the English crown since the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine and King Henry II. Joan and Edward then moved to Bordeaux, the capital of Aquitaine, where they spent the next nine years. Both of their children were born in France:

- Edward of Angoulême (1365 – 1372), died of the plague at the age of five

- Richard of Bordeaux, later King Richard II of England (1367 – 1400), married (1) Anne of Bohemia, no issue (2) Isabella of Valois (no issue)

Edward of Angouleme and Joan of Kent, depicted on the Wilton Diptych, 1395; Credit – Wikipedia

Richard II of England, portrait at Westminster Abbey, mid-1390s; Credit – Wikipedia

Around the time of the birth of his younger son, Edward was lured into an unsuccessful war on behalf of King Pedro of Castile. Edward contracted an illness during this war that ailed him until he died in 1376. It was believed that he contracted dysentery, which killed more medieval soldiers than battle, but it is unlikely that he could survive a ten-year battle with dysentery. Other possible diagnoses include edema, nephritis, or cirrhosis. By 1371, Edward could no longer perform his duties as Prince of Aquitaine and returned to England. In 1372, he forced himself to attempt one final campaign, hoping to save his father’s French possessions, but the prevailing winds off the shores of France prevented the ships from landing and the campaign was aborted.

Edward’s health was now completely shattered. On June 8, 1376, a week before his forty-sixth birthday, Edward died at the Palace of Westminster. His father King Edward III died a year later, on June 21, 1377, and was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson King Richard II, the surviving son of Edward the Black Prince. Edward had requested to be buried in the crypt at Canterbury Cathedral. He was buried at Canterbury Cathedral but not in the crypt. He was buried in a tomb with a bronze effigy on the south side of the shrine of Thomas Becket behind the choir. Edward’s heraldic helmet and gauntlets were placed above his tomb. Today, replicas hang above his tomb and the originals are in a glass case nearby. The epitaph inscribed around his effigy:

Such as thou art, sometime was I.

Such as I am, such shalt thou be.

I thought little on th’our of Death

So long as I enjoyed breath.

On earth I had great riches

Land, houses, great treasure, horses, money and gold.

But now a wretched captive am I,

Deep in the ground, lo here I lie.

My beauty great, is all quite gone,

My flesh is wasted to the bone.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

“Edward, the black prince.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Nov. 2016. Web. 1 Dec. 2016.

Joelson, Annette. England’s Princes of Wales. New York: Dorset Press, 1966. Print.

Toulouse illustrée, Histoire de. “Édouard de Woodstock.” Wikipedia. N.p.: Wikimedia Foundation, 23 June 1330. Web. 1 Dec. 2016.

Williamson, David. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell, 1996. Print.