by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

King John of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Born at Beaumont Palace in Oxford, England on December 24, 1167, King John of England was the fourth surviving son and the youngest of the eight children of King Henry II of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right. His mother was around 44 years old at the time of his birth.

John had seven siblings:

- William IX, Count of Poitiers (1153 – 1156), died in childhood

- Henry the Young King (1155 – 1183), married Marguerite of France, no children

- Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria (1156 – 1189), married Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, had five children, including Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

- King Richard I of England (1157 – 1199), married Berengaria of Navarre, no children

- Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany (1158 – 1186), married Constance, Duchess of Brittany, had three children

- Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile (1162 – 1214), married King Alfonso VIII of Castile, had twelve children including King Enrique I of Castile; Berengaria, Queen Regnant of Castile and Queen of León; Urraca, Queen of Portugal; Blanche, Queen of France, and Eleanor, Queen of Aragon

- Joan of England, Queen of Sicily (1165 – 1199), married (1) King William II of Sicily, no surviving children (2) Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, had two children, Joan died in childbirth with her third child who also died

13th-century depiction of Henry and his legitimate children: (l to r) William, Young Henry, Richard, Matilda, Geoffrey, Eleanor, Joan, and John; Credit – Wikipedia

John also had two half-sisters from his mother’s first (annulled) marriage to King Louis VII of France:

-

- Marie of France (1145 – 1198), married Henry I, Count of Champagne, had issue

- Alix of France (1151 – 1197/1198), married Theobald V, Count of Blois, had issue

As a young child, John was sent to Fontevrault Abbey in his father’s possession of Anjou. Later, he was brought up in the household of his eldest brother Henry the Young King, who was crowned king during his father’s reign as was customary in the French monarchy. His teacher was Ranulf de Glanville, a legal scholar, and later the Chief Justiciar of England. As a young child, John received the nickname Lackland from his father because it appeared he would not inherit substantial land like his three elder brothers. Henry the Young King would be King of England and receive his father’s Duchy of Normandy and the County of Anjou. Richard was to receive his mother’s possessions, the Duchy of Aquitaine and the County of Poitou. Geoffrey was to become Duke of Brittany through his marriage.

As Henry’s children grew up, tensions over the future inheritance of the empire began to emerge, encouraged by King Louis VII of France and then his son King Philippe II of France. In 1173, Henry the Young King rebelled in protest and was joined by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey, and their mother Eleanor. France, Scotland, Flanders, and Boulogne allied themselves with the rebels. Henry II eventually defeated the revolt and had Eleanor imprisoned for the next sixteen years for her part in inciting their sons.

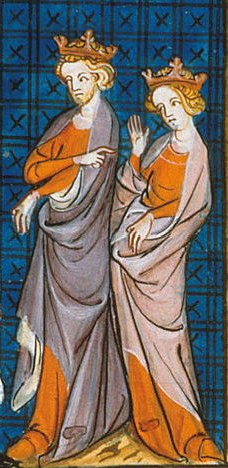

John’s parents, Henry II and Eleanor, holding court; Credit – Wikipedia

After the revolt of his sons, Henry II promised John an annuity of 1,000 pounds from England and 1,000 livres from Normandy and Anjou. Little by little, Henry II began to find land for John, usually at his nobles’ expense. When Reginald de Dunstanville, 1st Earl of Cornwall died in 1175 without surviving legitimate male offspring, Henry II gave the estates to John.

In 1176, Henry betrothed John to Isabella of Gloucester, the daughter of William Fitz Robert, 2nd Earl of Gloucester. The 2nd Earl was a first cousin of King Henry II as his father Robert Fitzroy, 1st Earl of Gloucester was the illegitimate son of King Henry I and Henry II’s mother Empress Matilda was the legitimate daughter of King Henry I. Robert was Matilda’s chief military support during her long civil war with their cousin Stephen of Blois (King Stephen of England) for the English throne. Isabella stood to inherit part of her father’s estate along with her two elder sisters because their only brother had died. However, Henry disinherited Isabella’s elder sisters so that John would eventually receive the whole Gloucester estate. As Isabella was only three and John was only nine, the marriage had to be delayed.

In 1185, Henry II sent 18-year-old John to Ireland as Lord of Ireland to complete the Norman conquest of Ireland. John arrived in Ireland in April 1185 and by December 1185, he was back in England, most likely due to the lack of money and the rude nature with which he treated the Irish leaders.

Henry the Young King; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1182 – 1183, Henry the Young King had a falling out with his brother Richard when Richard refused to pay homage to him on the orders of King Henry II. As he was preparing to fight Richard, Henry the Young King became ill with dysentery (also called the bloody flux), the scourge of armies for centuries, and died. In 1186, Henry II’s third son Geoffrey was trampled to death during a jousting tournament in Paris, leaving a posthumous son Arthur I, Duke of Brittany and a daughter Eleanor.

By the time Henry II turned age 56 in 1189, he was prematurely aged. Two sons were left: Richard, the second son, Eleanor’s favorite and the heir since his elder brother’s death, and John, the youngest child and Henry’s favorite. King Philip II of France successfully played upon Richard’s fears that Henry would make John King, and a final rebellion broke out in 1189. Decisively defeated by Philip and Richard and suffering from a bleeding ulcer, Henry retreated to his favorite residence, the Château de Chinon in Anjou. There he was told that John had publicly sided with Richard in the rebellion, and this broke his heart. Only his illegitimate son Geoffrey, Archbishop of York was at his father’s deathbed when King Henry II died on July 6, 1189.

King Henry II of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Upon hearing of his father’s death, Richard set out for England, stopping at Rouen, the capital of the Duchy of Normandy, where he was invested as Duke of Normandy on July 20, 1189. He was crowned King Richard I of England at Westminster Abbey on September 3, 1189. A few days earlier, on August 29, 1189, John and Isabella of Gloucester were married at Marlborough Castle in Wiltshire, and John assumed the Earldom of Gloucester in her right. Because John and Isabella were second cousins, Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury declared the marriage null due to consanguinity. but he was overruled by Pope Clement III. The couple was not a good match and they had no children.

King Richard I of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Richard spent very little time in England, perhaps as little as six months, during his ten-year reign. Most of his reign was spent on Crusade, in captivity, or actively defending his lands in France. Richard was back in Normandy by Christmas 1189, preparing to leave on the Third Crusades. Later, when Richard was captured in Germany on his way home from the crusades, Eleanor negotiated his ransom by going to Germany. At the same time, John and King Philippe II of France, offered Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor 80,000 marks to hold Richard prisoner until September 1194, but the offer was rejected. Finally, with the ransom in the emperor’s possession, Richard was released on February 4, 1194. Philippe II of France warned Richard’s brother John, “Look to yourself. The devil is loose.”

When Richard arrived in England in March 1194, he found that John had been depleting the treasury and was planning to overthrow him. However, when Richard and John met in person, Richard forgave John and named him as his heir in place of their nephew Arthur, Duke of Brittany. Arthur was the posthumous son of John’s older brother Geoffrey and had a better primogeniture claim to the English throne than John. During Richard’s long absence, his enemies including King Philippe II of France threatened his French possessions. Richard spent most of his time regaining lost territory and strengthening his hold over his French possessions. In late March 1199, when Richard was dying of gangrene from an arrow wound, his mother Eleanor made her way to his deathbed. Richard died in his mother’s arms on April 6, 1199, and the last son John became King of England.

On April 25, 1199, John was invested as Duke of Normandy in Rouen, the capital. He then left for England and his coronation was held at Westminster Abbey on May 27, 1199. John’s next order of business was to have his marriage to Isabella of Gloucester annulled. Isabella had not been acknowledged as queen and the marriage was easily annulled using the grounds of consanguinity. John kept Isabella’s lands and Isabella did not contest the annulment. Isabella married two more times:

- Geoffrey de Mandeville, 2nd Earl of Essex in January 1214: King John charged Geoffrey 20,000 marks to buy her in marriage and to obtain her title, Jure uxoris, a Latin term that means “by right of his wife.” The marriage had no issue and Geoffrey died in 1216.

- Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent in September 1217: Within a few weeks, on October 14, 1217, Isabella died at age 43 and was buried at Canterbury Cathedral. Isabella’s nephew Gilbert de Clare, the son of her sister, Amice and Richard de Clare, became the 5th Earl of Gloucester.

Isabella of Angoulême; Credit – Wikipedia

It came to John’s attention that 12-year-old Isabella of Angoulême, the only child of Aymer III, Count of Angoulême and therefore destined to be Countess of Angoulême in her own right, had become betrothed to Hugh de Lusignan, the heir of Hugh IX de Lusignan, Count of La Marche. This marriage would join La Marche and Angoulême, and the de Lusignan family would then control a vast, rich, and strategic territory between the two Plantagenet strongholds, Bordeaux and Poitier. To prevent this threat, King John of England decided to marry Isabella. Isabella of Angoulême’s parents had no objection to the marriage with the 34-year-old John. After all, he was a king and their daughter would be a queen. Isabella and John were married on August 24, 1200, and then Isabella was crowned Queen of England on October 8, 1200, at Westminster Abbey. Isabella’s father died in 1202, and she succeeded him as Countess of Angoulême in her own right. However, her title was largely empty because John denied the control of her inheritance. John appointed a governor, Bartholomew de Le Puy, who conducted most of the administrative affairs of Angoulême until John died in 1216.

John and Isabella had five children:

- King Henry III of England (1207 – 1272), married Eleanor of Provence, had five children including King Edward I of England

- Richard, Earl of Cornwall, King of the Romans (1209 – 1272), married (1) Isabel Marshal, had three sons and a daughter, only one son survived childhood, Isabel died in childbirth (2) Sanchia of Provence, had two sons, only one son survived childhood (3) Beatrice of Falkenburg, no children

- Joan of England (1210 – 1238), married Alexander II, King of Scots, no children

- Isabella of England (1214 – 1241), married Friedrich II, Holy Roman Emperor, had at least four children

- Eleanor of England (1215 – 1275), married (1) William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, no children (2) Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, had seven children

13th-century depiction of John and his children, (l to r) Henry, Richard, Isabella, Eleanor, and Joan; Credit – Wikipedia

John had many illegitimate children. His most noteworthy one was a daughter Joan (or Joanna) In 1205, Joan married Llywelyn Fawr (Llywelyn the Great), Prince of Gwynedd and Prince of Powys Wenwynwyn. In 1216, Llewellyn received the allegiance of other Welsh lords and although he never used the title, was the de facto Prince of Wales. Llywelyn dominated Wales for 45 years, and was one of only two Welsh rulers to be called “the Great.” Joan, Llywelyn, and their family are among the characters in Sharon Penman‘s historical fiction trilogy, The Welsh Trilogy.

When John became King, the succession had bypassed the children of his deceased elder brother Geoffrey who had better claims to the throne based upon the laws of primogeniture. In 1166, as part of an agreement by Henry II to end his attacks on Conan IV, Duke of Brittany, Geoffrey had been betrothed to Conan’s daughter and heir Constance. The couple married in 1181 and had two surviving children, Arthur, who became Duke of Brittany upon his father’s death in 1186, and Eleanor, known as the Fair Maid of Brittany.

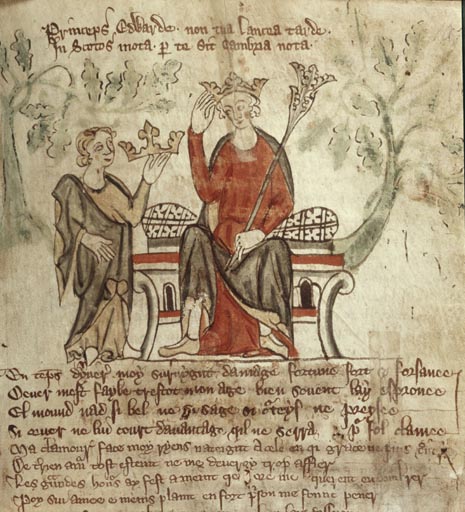

Arthur I, Duke of Brittany paying homage to King Philip II of France; Credit – Wikipedia

Many members of the French nobility refused to recognize John upon his accession to the English throne and his French lands. They believed that Arthur had a better claim because his father was John’s elder brother. In 1202, 15-year-old Arthur started a campaign against his uncle John in Normandy with the support of King Philip II of France. John’s territory of Poitou revolted in support of Arthur. Arthur besieged his grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, John’s mother, in the Château de Mirebeau in Poitou. John marched on Mirebeau, taking Arthur by surprise on July 31, 1202. Arthur was captured and imprisoned in the Château de Falaise in Falaise, Normandy. By 1203, Arthur had disappeared. His fate is unknown, but presumably, he was murdered on the orders of his uncle John.

Eleanor of Brittany; Credit – Wikipedia

Arthur’s sister Eleanor was also King John’s prisoner because she and any future children posed a threat to John’s throne. She remained imprisoned for her entire life, into the reign of John’s son King Henry III of England, dying in 1241 at the age of 57 or 59. Her imprisonment in England made it impossible for her to claim her inheritance as Duchess of Brittany. During her 39-year imprisonment, Eleanor, apparently innocent of any crime, was never tried or sentenced. She was considered a state prisoner, was forbidden to marry, and guarded closely even after her childbearing years. Arthur was succeeded by his half-sister Alix of Thouars, the daughter of his mother Constance and her third husband Guy of Thouars.

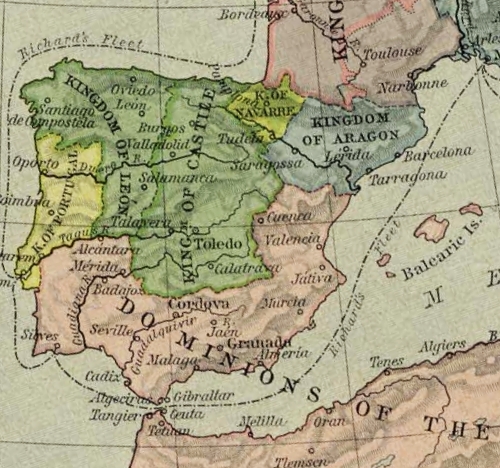

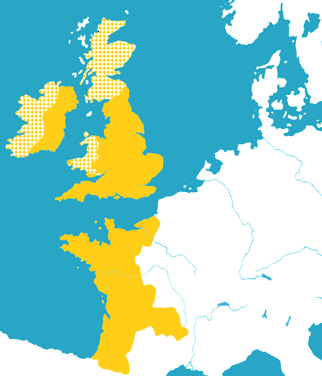

Angevin Empire around 1172, solid yellow shows Angevin possessions, checked yellow shows areas where there was Angevin influence; By Cartedaos (talk) 01:46, 14 September 2008 (UTC) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4781085

At the time of John’s accession to the English throne, his territories, the Angevin Empire, formed by his paternal grandparents, Geoffrey V of Anjou and Empress Matilda, his parents King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, and preserved and protected by his brother King Richard I of England, were basically what appears on the map above. The apparent murder of Arthur, Duke of Brittany on the orders of John, outraged King Philip II of France. Philip, as the overlord of both the Duchy of Brittany and John’s possession, the Duchy of Normandy, declared Normandy forfeit and began an invasion. Château Gaillard, built to defend Normandy by John’s brother King Richard I, fell to Philip in March 1204. In June 1204, the French king entered Rouen, the capital city of Normandy. Philip’s war against John eventually cost John his territories of Normandy, Maine, Touraine, Anjou, and Poitou, all ancestral territories of his Norman or Angevin ancestors.

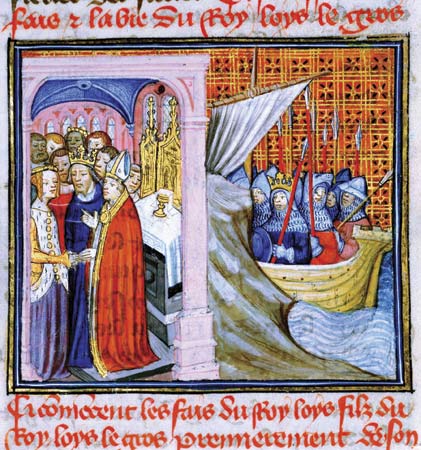

King John and King Philip II of France making peace with a kiss; Credit – Wikipedia

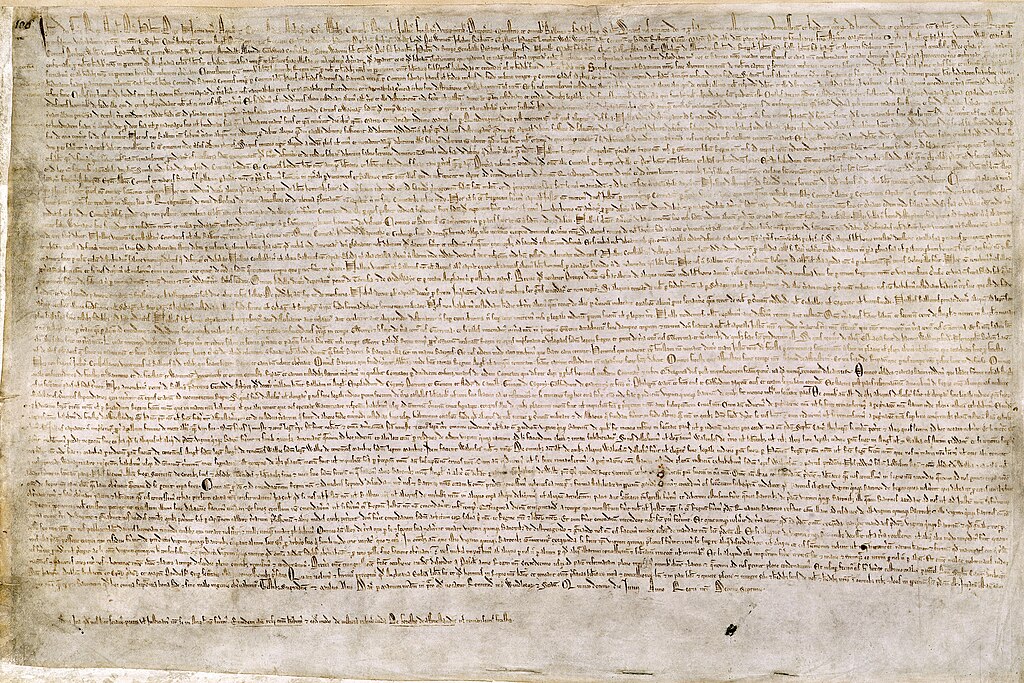

While John was trying to save his French territories, his discontented English barons led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, were protesting John’s continued misgovernment of England. The result of this discontent was the best-known event of John’s reign, the Magna Carta, the “great charter” of English liberties, forced from King John by the English barons and sealed at Runnymede near Windsor Castle on June 15, 1215. Among the liberties were the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown. The Magna Carta is still an important symbol of liberty and is held in great respect by the British and American legal communities. Four versions of the original 1215 charter remain in existence. Two are held by the British Library and one each is at Lincoln Cathedral and Salisbury Cathedral.

One of the remaining four versions of the original Magna Carta; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Infuriated by being forced to agree to the Magna Carta, John turned to Pope Innocent III, who declared the Magna Carta null and void and the rebel barons excommunicated. The conflict between John and the barons was transformed into an open civil war, the First Barons’ War (1215-1217). The rebels appealed to the French king and offered his son, the future King Louis VIII, the English crown. The war continued after John’s death, but William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, slowly managed to get most barons to switch sides from Louis to the new King Henry III and attack Louis. The Magna Carta was reissued in King Henry III’s name with some of the clauses omitted and was sealed by the nine-year-old king’s regent William Marshal.

King John of England in battle with the Franks (left), Louis VIII of France on the march (right); Credit – Wikipedia

Amid the First Barons’ War, John was traveling through East Anglia, from Spalding in Lincolnshire to Bishop’s Lynn, in Norfolk, became ill with dysentery, and decided to turn back, taking the longer road route. However, he sent his baggage train, including his crown jewels, through The Wash, the large indentation in the coastline of Eastern England that separates the curved coast of East Anglia from Lincolnshire. This route, flat, low-lying, and often marshy, was usable only at low tide. The horse-drawn wagons moved too slowly for the incoming tide, and many were lost.

John managed to ride to Swineshead Abbey where he spent the night. The next day, he was taken by a litter to Newark Castle where he died on October 19, 1216, at the age of 49. At his request, King John was buried in Worcester Cathedral as close to the shrine of St. Wulfstan as possible. A new tomb was made in 1232, during the reign of his son and heir King Henry III.

King John’s Tomb; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1217, John’s widow Isabella of Angoulême left her young son King Henry III of England in the care of his regent, William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, and returned to France to assume control of her inheritance, the County of Angoulême. There, she once again met her jilted fiancé Hugh de Lusignan, now the 10th Count of La Marche, who had never married. Isabella and Hugh married on May 10, 1220, and they had nine children. Isabella died on May 31, 1246, at Fontevrault Abbey and was initially buried in the common graveyard there at her request. In 1254, her son King Henry III visited Fontevrault and personally supervised the reburial of his mother’s remains in the abbey church next to the tombs of his grandparents King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

England: House of Angevin Resources at Unofficial Royalty