by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2016

Prince George of Denmark, Duke of Cumberland; Credit – Wikipedia

The husband of Queen Anne of Great Britain, Prince George of Denmark (Jørgen in Danish) was born at Copenhagen Castle in Denmark on April 2, 1653. He was the younger of the two sons and the fifth of the eight children of King Frederik III of Denmark and Sophie Amalie of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

George had seven siblings:

- King Christian V of Denmark (1646 – 1699), married Charlotte Amalie of Hesse-Kassel; had issue

- Anna Sophie (1647 – 1717), married Johann Georg III, Elector of Saxony; had issue

- Frederica Amalia (1649 – 1704), married Christian Albert, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp; had issue

- Wilhelmina Ernestina (1650 – 1706), married to Karl II, Elector Palatine

- Ulrika Eleonora (1656 – 1693), married King Karl XI of Sweden, had issue

- Frederik (1651 – 1652), died in infancy

- Dorothea (1657 – 1658), died in infancy

George was educated by the Hanoverian statesman Baron Otto Grote zu Schauen and then later by Danish Bishop Christen Jensen Lodberg. From 1668 – 1669, George undertook the traditional Grand Tour and visited France, England, Italy, and Germany. After the death of his father in 1670, he returned to Denmark, when his older brother succeeded to the throne as King Christian V. In 1674, George was briefly a candidate for the Polish throne, however, from the outset, there was little chance of success because George was a staunch Lutheran and would not convert to Catholicism.

On July 28, 1683, at the Chapel Royal in St. James’ Palace in London, England, George married Anne of England (the future Queen Anne), the youngest of the two surviving daughters of James, Duke of York (the future King James II of England) and his first wife Anne Hyde. Even though the marriage was arranged, the marriage was happy and they were faithful to each other. The couple’s London residence was a set of buildings at Whitehall Palace in London, England, called the Cockpit-in-Court.

Anne, circa 1684; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince George of Denmark, circa 1687; Credit – Wikipedia

Anne became pregnant a few months after the wedding, but she gave birth to a stillborn daughter in May 1684. Anne’s obstetrical history is tragic. She had 17 pregnancies with only five children being born alive. Two died on the day of their birth, two died at less than two years old within six days of each from smallpox, and one died at age 11. Anne suffered from what was diagnosed as gout and had pain in her limbs, stomach, and head. Based on these symptoms and her obstetrical history, Anne may have had systemic lupus erythematosus which causes an increased rate of fetal death.

- Stillborn daughter (May 12, 1684)

- Mary (June 2, 1685 – February 8, 1687), died of smallpox

- Anne Sophia (May 12, 1686 – February 2, 1687), died of smallpox

- Miscarriage (January 21, 1687)

- Stillborn son (October 22, 1687)

- Miscarriage (April 16, 1688)

- Prince William, Duke of Gloucester (July 24, 1689 – July 30, 1700)

- Mary (born and died October 14, 1690)

- George (born and died April 17, 1692)

- Stillborn daughter (March 23, 1693)

- Miscarriage (January 21, 1694)

- Miscarriage of daughter (February 17 or 18, 1696)

- Miscarriage (September 20, 1696)

- Miscarriage (March 25, 1697)

- Miscarriage of twins (early December 1697)

- Stillborn son (September 15, 1698)

- Stillborn son (January 24, 1700)

Anne and her longest surviving child, Prince William, Duke of Gloucester; Credit – Wikipedia

George was naturalized as an English subject in 1683, invested as a Knight of the Garter in 1684, and created Duke of Cumberland, Earl of Kendal, and Baron Wokingham in 1689. Prince George played no part in politics and had no real ambitions. His uncle by marriage, King Charles II, famously said of George, “I have tried him drunk, and I have tried him sober, and drunk or sober, there is nothing there.

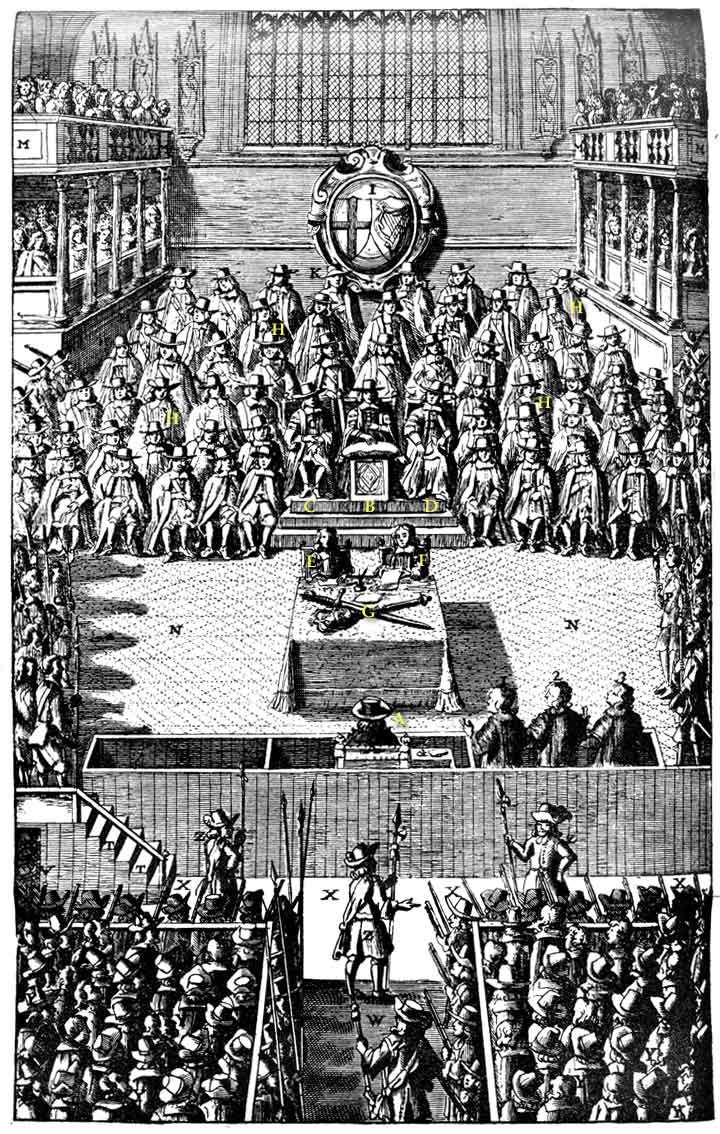

Upon the death of King Charles II in 1685, George’s father-in-law the Roman Catholic Duke of York came to the throne as King James II. Anne and George became the center of Protestant opposition against the new king. On November 5, 1688, William III, Prince of Orange landed in England with an invasion army. Married to Anne’s elder sister Mary, William III, Prince of Orange was the only child of Mary, Princess Royal, the eldest daughter of King Charles I of England, so he was third in the line of succession to the throne. The Glorious Revolution resulted, James fled to France, and Anne’s sister and brother-in-law became joint monarchs, King William III and Queen Mary II

On December 28, 1694, Anne’s sister Queen Mary II died of smallpox. She was just 32 years old. King William III continued to reign alone for the remainder of his life. As William and Mary had no children, Anne was now the heir presumptive to the throne and her son William was second in the line of succession.

On July 24, 1700, Anne’s son Prince William, Duke of Gloucester celebrated his eleventh birthday at a party held at Windsor Castle. Jenkin Lewis, his servant, reported, “He complained a little the next day, but we imputed that to the fatigues of a birthday so that he was much neglected.” In the evening, William complained of a sore throat and chills. Two days later, he was no better and had developed a fever and was delirious. The doctors suspected smallpox, but no rash appeared, so they used the usual treatments of the time, bleeding and blistering, which no doubt, made William’s condition worse. William died on the morning of July 30, 1700, at Windsor Castle, probably of pneumonia. His body was taken to the Palace of Westminster where it lay in state in his apartments. William was interred in the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey during the evening of August 7, 1700. His uncle, King William III wrote to the Duke of Marlborough, that William’s death was “so great a loss to me as well as to all of England, that it pierces my heart.”

Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, shortly before his death; Credit – Wikipedia

Anne and her husband George were devastated. This death and the failure of the Protestant Stuarts to produce heirs meant the end of the Protestant Stuart dynasty as the legitimate descendants of King Charles I were either childless or Roman Catholic. The Act of Settlement 1701 secured the Protestant succession to the throne after William’s sister-in-law and heir presumptive Princess Anne. The act excluded the former King James II (who died a few months after the act received royal assent) and the Roman Catholic children from his second marriage and also excluded the descendants of King James II’s sister Henrietta, the youngest daughter of King Charles I. Parliament’s choice was limited to the Protestant descendants of Elizabeth Stuart, Electress Palatine, the only other child of King James I not to have died in childhood. The senior Protestant descendant was Elizabeth’s youngest daughter Sophia, Electress of Hanover. The Act of Settlement put Sophia of Hanover and her Protestant heirs in the line of succession after Anne.

On February 20, 1702, King William III went riding on his horse at Hampton Court Palace. The horse stumbled on a molehill and fell and broke his collarbone. After a surgeon set his collarbone, William refused to rest. He insisted on returning to Kensington Palace. A week later, the fracture was not mending well and William’s right hand and arm were puffy and did not look right. His condition continued to worsen and by March 3, William had a fever and had difficulty breathing. King William III died on March 8, 1702, and was succeeded by his sister-in-law and cousin Anne.

Queen Anne’s coronation took place on St George’s Day, April 23, 1702. Despite being only 37 years old, Anne was so overweight and infirm that she had to be carried in a sedan chair to Westminster Abbey. At the coronation, Anne’s husband Prince George paid homage to her. He was the first husband of a reigning queen to do so and it was not to be repeated until Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh paid homage to his wife Queen Elizabeth II at her 1953 coronation.

Anne with her husband, Prince George of Denmark, painted by Charles Boit, 1706; Credit – Wikipedia

In March and April 1706, George became seriously ill but seemed to recover. He spent much of the summer of 1708 at Windsor Castle with asthma that was so bad he was not expected to live. Prince George died on October 28, 1708, at Kensington Palace in London at the age of 55. Queen Anne deeply grieved for him. She was desperate to remain with George’s body but reluctantly left after persuasion from her childhood friend and favorite Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. George was buried privately at midnight on November 13, 1708, at Westminster Abbey in a vault under the monument to George Monck, Duke of Albemarle in the Henry VII Chapel. Charles II, William III, Mary II, and George’s wife Anne were also buried in this vault.

Inscription on the floor of the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey marking the graves of Queen Anne and Prince George; Credit – findagrave.com

Stuart Royal Vault at Westminster Abbey; Photo Credit – www.westminster-abbey.org

House of Stuart Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Index

- House of Stuart Index

- Coronations after the Norman Conquest (1066 – present)

- History and Traditions: Stuart Weddings

- House of Stuart Burial Sites

- House of Stuart Christenings

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.