by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2014

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of the United Kingdom; Credit – Wikipedia

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was born at the Untere Schloss (Lower Castle) (scroll down) in Mirow, Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, now in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, on May 19, 1744. Charlotte was the youngest daughter and the eighth of ten children of Duke Carl Ludwig Friedrich of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Princess Elisabeth Albertine of Saxe-Hildburghausen. Charlotte’s father died when she was eight-years-old and her mother died when she was 17, shortly before Charlotte married.

Charlotte had nine siblings:

- Duchess Christiane of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1735 – 1794), unmarried

- Duchess Caroline of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1736), died in infancy

- Adolph Friedrich IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1738 – 1794), unmarried

- Duchess Elisabeth Christine of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1739 – 1741), in early childhood

- Duchess Sophie Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1740 – 1742), died in early childhood

- Carl II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg (1741 – 1816), married (1) Princess Friederike of Hesse-Darmstadt, had issue (2) his first wife’s sister Princess Charlotte of Hesse-Darmstadt, had issue

- Duke Ernst Gottlob Albrecht of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1741 – 1814), unmarried

- Duke Gotthelf of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (born and died 1745), died in infancy

- Duke Georg August of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1748 – 1785), unmarried

At the time of Charlotte’s birth, Great Britain was ruled by King George II and his heir was his eldest son, Frederick, Prince of Wales. Frederick predeceased his father in 1751 and his eldest son George became heir to the throne. When King George II died in 1760, his 22-year-old grandson succeeded him as King George III. Before George became king, two attempts to marry him had failed and now that he had succeeded to the throne, the search for a wife intensified. The choice fell upon Charlotte and George’s mother Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales probably played a major role in the decision.

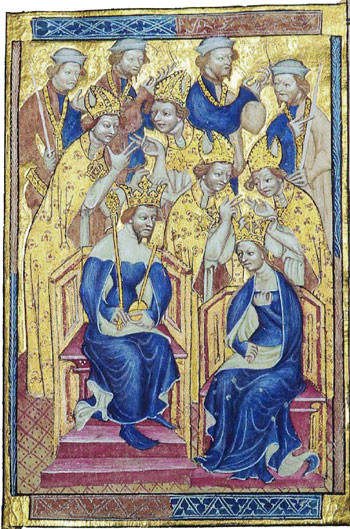

Charlotte’s journey to London took ten days and included a very stormy crossing of the British Channel. While most of her attendants were seasick, Charlotte practiced playing “God Save the King” on the harpsichord. On September 8, 1761, at 10 PM, George and Charlotte married in the Chapel Royal of St. James’ Palace in London, England. On September 22, 1761, their coronation was held at Westminster Abbey in London, England.

Coronation Portraits of King George III and Queen Charlotte by Allan Ramsey; Credit -http://www.royalcollection.org.uk

George and Charlotte’s marriage was a very happy one, and George remained faithful to Charlotte. Between 1762 – 1783, Charlotte gave birth to 15 children, and all survived childbirth. Only two of the children did not survive childhood. It is remarkable that in 1817 at the time of the death in childbirth of Princess Charlotte of Wales, who was second in line to the throne after her father the Prince of Wales, Princess Charlotte was the only legitimate grandchild of King George III, despite the fact that eleven of his fifteen children were still living.

The 15 children of King George III and Queen Charlotte:

- King George IV (1762 – 1830), married Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, had issue: Princess Charlotte of Wales who died in childbirth as did her child

- Prince Frederick, Duke of York (1763 – 1827), married Frederica of Prussia, no issue

- King William IV (1765 – 1837), married Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, no surviving legitimate issue, had illegitimate children

- Charlotte, Princess Royal (1766 – 1828), married King Friedrich I of Württemberg, no surviving issue

- Prince Edward, Duke of Kent (1767 – 1820), married Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, had issue: Queen Victoria, present British Royal Family are his descendants

- Princess Augusta Sophia (1768 -1840), never married, no issue

- Princess Elizabeth (1770 – 1840), married Friedrich, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg, no issue

- King Ernest Augustus I of Hanover, Duke of Cumberland (1771 – 1851), married Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz; had issue, has descendants today

- Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex (1773 – 1843), married twice, both in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 1) Lady Augusta Murray, had issue, marriage annulled 2) Lady Cecilia Buggin (later 1st Duchess of Inverness), no issue

- Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge (1774 – 1850), married Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, had issue, has descendants today, present British Royal Family are his descendants through his granddaughter Mary of Teck who married King George V of the United Kingdom

- Princess Mary (1776 – 1857), married Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester, no issue

- Princess Sophia (1777 – 1848), never married, possible illegitimate issue

- Prince Octavius (1779 – 1783), died in childhood

- Prince Alfred (1780 – 1782), died in childhood

- Princess Amelia (1783 – 1810), never married, no issue

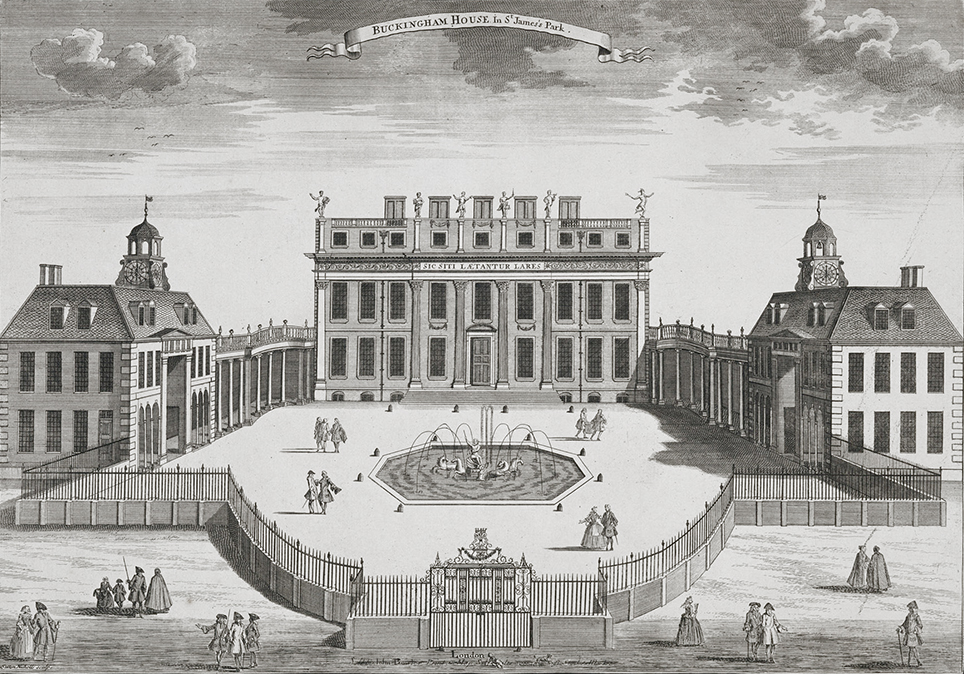

In the same year as his marriage, King George III purchased Buckingham House, originally built for John Sheffield, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Normanby in 1703. Originally purchased as a get-away for Charlotte who gave birth to 14 of her 15 children there, the house became known as the Queen’s House and was the architectural core of the present Buckingham Palace.

Buckingham House around 1710; Credit – Wikipedia

George and Charlotte led a simple life with their children, residing at the Queen’s House, Windsor Castle, and Kew Palace. The family took summer holidays at Weymouth in Dorset, England making Weymouth one of the first seaside resorts in England. The simplicity of the royal family’s life dismayed some of the courtiers. Upon hearing that the King, Queen, and the Queen’s brother went for a walk by themselves in Richmond, Lady Mary Coke said, “I am not satisfied in my mind about the propriety of a Queen walking in town unattended.”

Charlotte played no part in politics and was content in dealing with family affairs. She had some charities including the silk weavers of Spitalfields, but she spent most of her time dealing with her growing family. George and Charlotte were possessive parents and often made unwise decisions regarding their family. Charlotte thought the Prince of Wales could do no wrong and encouraged him in the cruel treatment of his wife Caroline. Charlotte and George’s six daughters were well brought up, kind and considerate, but all attempts by young, eligible men to marry them were stymied.

Queen Charlotte by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1789; Credit – Wikipedia

The only disruption in the family’s domestic lives was George’s attacks of illness. We now know that King George possibly suffered from porphyria and his attacks severely worried Charlotte. The stress caused by her husband’s illness caused Charlotte’s personality to change. She became bad-tempered and depressed and her relationships with her children were strained. In 1810, George became so ill that Parliament needed to pass the Regency Act of 1811. The Prince of Wales acted as Regent until his father died in 1820. Charlotte was her husband’s legal guardian, but could not bring herself to visit him due to his violent outbursts and erratic behavior.

Charlotte was extremely upset at the death of her granddaughter and namesake Princess Charlotte of Wales in 1817. She had been in Bath at the time of her granddaughter’s death and was criticized for not being present. During the last year of her life, Charlotte presided over the weddings of her aging sons who were marrying to provide heirs to the throne after the death of Princess Charlotte of Wales.

Queen Charlotte died on November 17, 1818, at Kew Palace seated in a small armchair holding the hand of her eldest son. She was buried in the Royal Tomb House at St. George’s Chapel Windsor. Charlotte is the second longest-serving consort in British history. Only her descendant, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, husband of Queen Elizabeth II, served as a consort longer. King George III was unaware of his wife’s death. He died at Windsor Castle on January 29, 1820, six days after the death of his fourth son, Edward, Duke of Kent. The Duke of Kent’s only child, a daughter, was only eight months old when her father died, but 17 years later she succeeded to the throne as Queen Victoria.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

House of Hanover Resources at Unofficial Royalty