by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

King Charles III & Queen Camilla wave from the Buckingham Palace balcony after their coronation; Credit – By HM Government – https://coronation.gov.uk/OGL 3, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=133959751

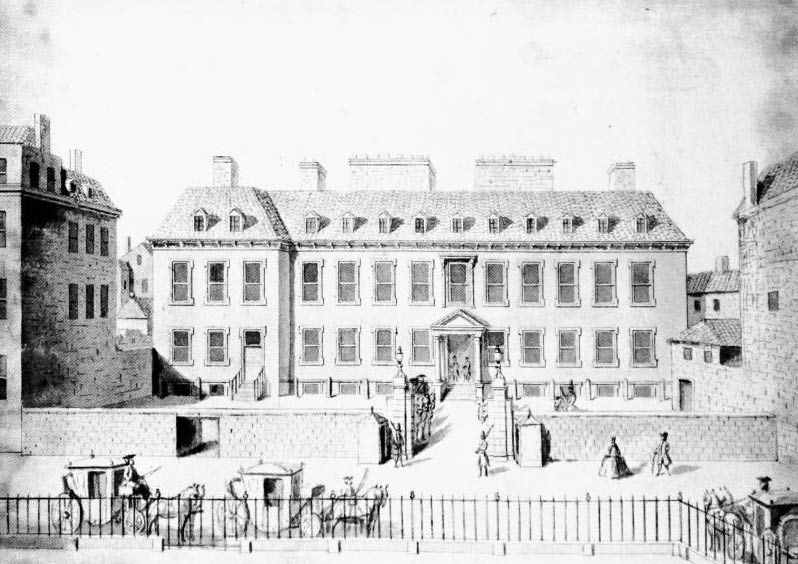

King Charles III acceded to the British throne on September 8, 2022, upon the death of his mother Queen Elizabeth II, the longest-reigning British monarch, having reigned 70 years, 214 days. The coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla took place at Westminster Abbey in London, England on Saturday, May 6, 2023, at 11:00 AM British Time.

Westminster Abbey; Photo Credit – By Σπάρτακος – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26334184

********************

The Procession

The Diamon Jubilee State Coach; Credit – By Grahamedown – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9426700

King Charles III and Queen Camilla arrived at Westminster Abbey in a procession that started from Buckingham Palace. They arrived in the 2014 Diamond Jubilee State Coach and returned to Buckingham Palace in the 1762 Gold State Coach.

The procession route was only 1.3 miles. The same route was used for the return trip to Buckingham Palace. The route is the normal route royals use to get to Westminster Abbey: leaving Buckingham Palace through the Centre Gate, and proceeding down The Mall, passing through Admiralty Arch and south of King Charles I Island, down Whitehall and along Parliament Street, around the east and south sides of Parliament Square to Broad Sanctuary, arriving at Westminster Abbey.

Queen Elizabeth II had somewhat the same route to the Abbey with a small .3-mile addition but had a five-mile return trip. On the map above, Charles’ route to and from is in red, Elizabeth’s route to the Abbey is in light blue and her route back to Buckingham Palace is in dark blue. Elizabeth’s route allowed for people to stand on 5.3 miles of street while Charles’ route allowed for people to stand on only 1.3 miles of street.

Participants

One of King Charles III’s grandchildren and three of Queen Camilla’s grandchildren and one of her great-nephews participated in the coronation.

Four pages of honour attended King Charles III:

Four pages of honour attended Queen Camilla:

- Gus Lopes, the Queen’s grandson, son of her daughter Laura Lopes

- Louis Lopes, the Queen’s grandson, son of her daughter Laura Lopes

- Frederick Parker Bowles, the Queen’s grandson, son of her son Tom Parker Bowles

- Arthur Elliot, the Queen’s great-nephew, son of her nephew Ben Elliot

In addition, Queen Camilla had two Ladies in Attendance:

Some Peers of the Realm carried standards, banners, and the coronation regalia in the procession and/or presented regalia during the coronation. Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal of England is the most senior peer in the Peerage of England. The Earl Marshal is a hereditary royal officeholder. The Dukes of Norfolk have held the office since 1672. The Earl Marshal organizes major ceremonial state occasions such as the monarch’s coronation and state funerals. He is also the leading officer of arms, oversees the College of Arms, and is the sole judge of the High Court of Chivalry.

Peers of the Realm Who Participated in the Coronation

- Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal of England

- Richard Scott, 10th Duke of Buccleuch and 12th Duke of Queensberry, carried the Sceptre with Cross

- Charles Wellesley, 9th Duke of Wellington, carried Queen Mary’s Crown

- Hugh Grosvenor, 7th Duke of Westminster, carried the Standard of the Royal Arms of England

- Charles Paget, 8th Marquess of Anglesey, carried the Standard of the Principality of Wales

- Anthony Lindsay, 30th Earl of Crawford and 13th Earl of Balcarres, Deputy to the Great Steward of Scotland

- Merlin Hay, 24th Earl of Erroll, Lord High Constable of Scotland

- Simon Abney-Hastings, 15th Earl of Loudoun, carried the Golden Spurs

- Alexander Scrymgeour, 12th Earl of Dundee, carried the Royal Banner of Scotland

- Nicholas Alexander, 7th Earl of Caledon, carried the Standard of the Royal Arms of Ireland

- Delaval Astley, 23rd Baron Hastings, carried the Golden Spurs

- Rupert Carington, 7th Baron Carrington, Lord Great Chamberlain of England, presented the Golden Spurs

- Valerie Amos, Baroness Amos, participated in the act of Recognition of His Majesty

- Helena Kennedy, Baroness Kennedy of The Shaws, carried The Queen Consort’s Rod

- Narendra Patel, Baron Patel, presented the Ring

- Elizabeth Manningham-Buller, Baroness Manningham-Buller, carried St. Edward’s Staff

- Floella Benjamin, Baroness Benjamin, carried the Sceptre with the Dove

- Nicholas True, Baron True, Leader of the House of Lords and Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

- Indarjit Singh, Baron Singh of Wimbledon, presented the Coronation Glove

- General David Richards, Baron Richards of Herstmonceux, carried the Sword of Spiritual Justice

- Angela Smith, Baroness Smith of Basildon, Leader of the Opposition in the House of Lords

- General Nicholas Houghton, Baron Houghton of Richmond, carried the Sword of Temporal Justice

- Richard Chartres, Baron Chartres, carried The Queen Consort’s Ring and presented The Queen Consort’s Sceptre with Cross

- Ara Darzi, Baron Darzi of Denham, carried the Armills

- Syed Kamall, Baron Kamall, presented the Armills

- Gillian Merron, Baroness Merron, presented the Robe Royal

- Air Chief Marshal Stuart William Peach, Baron Peach, carried the Sword of Mercy (The Curtana)

Armed Forces Who Participated in the Coronation

- General Sir Patrick Sanders, Chief of the General Staff, carried the Queen’s sceptre

- Cadet Warrant Officer Elliott Tyson-Lee, carried the Union Flag

- Petty Officer Amy Taylor, carried the Jewelled Sword of Offering

Others Who Participated in the Coronation

Penny Mordaunt memorably bore the heavy Sword of State throughout the coronation.

- Penny Mordaunt, Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons, presented the Jewelled Sword of Offering and carried the Sword of State

- Rupert Carington, 7th Baron Carrington, Lord Great Chamberlain, presented the Golden Spurs

- Rose Hudson-Wilkin, Bishop of Dover, presented The Queen Consort’s Rod

- John McDowell, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland, presented the Sovereign’s Orb

- Iain Greenshields, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, presented the Bible

- Mark Strange, Bishop of Moray, Ross and Caithness and Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church, presented the Sceptre with Cross

- Andrew John, Archbishop of Wales and Bishop of Bangor, presented the Sceptre with Dove

- John Armes, Bishop of Edinburgh, Usher of the White Rod

The Coronation Ceremony

King Charles III and Queen Camilla were crowned in Westminster Abbey in London in a service conducted by Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury assisted by David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster with other clergy participating.

Read about the British coronation regalia at the links below:

Like many other Christian churches, Westminster Abbey is built in the shape of a cross. The space where coronations happen, called the Coronation Theatre, is at the point at which the two parts of the cross meet, at the very center of Westminster Abbey, directly in front of the High Altar. It is here that the 700-year-old Coronation Chair, also called St. Edward’s Chair or King Edward’s Chair, is placed, facing the High Altar. The monarch sits on the Coronation Chair for the majority of the coronation service.

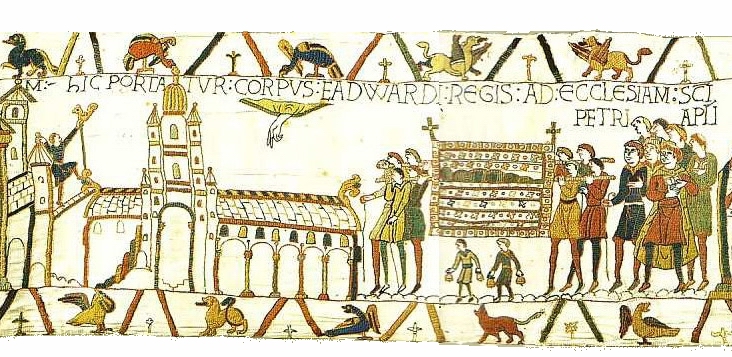

The coronation involves six basic stages based on the coronation service written by Saint Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury used in 973 for the coronation of Edgar the Peaceful, King of the English: the recognition, the oath, the anointing, the investiture/the crowning, the enthronement, and the homage.

The coronation service of King Charles III and Queen Camilla was shorter than past coronation services. The Coronation Liturgy for the coronation (link below) followed the six basic stages but the text of the service was quite different from the text of past coronations, and there were some changes from past coronations and some modern additions.

St. Edward’s Crown; Credit – By Firebrace – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116459012

King Charles III was crowned with the traditional St. Edward’s Crown and Queen Camilla was crowned with Queen Mary’s Crown, first worn by King Charles’ great-grandmother Queen Mary when she was crowned as Queen Consort with her husband King George V in 1911.

Coronation Music

The music at the coronation of King Charles III, who was very much involved in the music selection, featured twelve new orchestral, choral, and organ pieces commissioned for the coronation including a coronation anthem based on Psalm 98 by Andrew Lloyd Webber, Baron Lloyd Webber. One of the liturgical sections of the ceremony was performed in Welsh in tribute to King Charles III’s long tenure as Prince of Wales. At King Charles III’s request, Greek Orthodox music was included in tribute to his late father Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, born a Greek prince.

I Was Glad, with text from Psalm 122, has been sung at the entrance of the monarch at every coronation since that of King Charles I in 1626. Sir Hubert Parry wrote a setting of the psalm for the coronation of King Edward VII in 1902. It was also used for the coronations of King George V, King George VI, Queen Elizabeth II, and King Charles III.

At the coronation of every monarch since the coronation of King James II in 1685, the King’s (or Queen’s) Scholars of the Westminster School have had the privilege of acclaiming the monarch by shouting “Vivat” during the monarch’s procession from the Quire of Westminster Abbey towards the Coronation Theatre in front of the High Altar. The Vivat was incorporated into Sir Hubert Parry’s anthem I Was Glad, at the end. The Latin version of the names is used, and so “Vivat, Rex! / Vivat, Rex Carolus! / Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!” and “Vivat, Regina! / Vivat, Regina Camilla! / Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!” was heard.

In 1727, George Frederic Handel composed four coronation anthems for the coronation of King George II and his wife Queen Caroline. One of the anthems, Zadok the Priest, has been played at every British coronation since the coronation of King George II in 1727. It is traditionally performed just prior to the sovereign’s anointing, including at the coronation of King Charles III.

Zadok the Priest is the most famous of the anthems and is every bit as rousing as Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus from the oratorio The Messiah. The text of Zadok the Priest comes from the biblical account of the anointing of King Solomon of ancient Israel by Zadok, the High Priest of Israel and the prophet Nathan, and the rejoicing of the Israelites. These words have been used in every English coronation since King Edgar the Peaceful‘s coronation at Bath Abbey in 973.

From 1 Kings 1:34-45:

Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet anointed Solomon king.

And all the people rejoiced and said:

God save the King! Long live the King! God save the King!

May the King live forever. Amen. Hallelujah.

The Coronation Liturgy

Liturgy information is from THE AUTHORISED LITURGY FOR THE CORONATION RITE OF

HIS MAJESTY KING CHARLES III for use on Saturday 6th May 2023, 11:00 am at Westminster Abbey. Commissioned and Authorised by The Most Reverend & Right Honourable Justin Welby, The Archbishop of Canterbury. The liturgy and an excellent and informative commentary can be seen at the link below.

The Procession of The King & The Queen: As King Charles III and Queen Camilla entered Westminster Abbey, the choir sang I Was Glad by Sir Hubert Parry.

Greeting The King: A young person (a Chapel Royal chorister) greeted King Charles III, saying:

“Your Majesty, as children of the Kingdom of God we welcome you in the name of the King of Kings”. King Charles III responded: “In his name, and after his example, I come not to be served but to serve.”

Silent Prayer: King Charles III stood at his Chair of Estate, head bowed, in a moment of silent prayer.

Greeting and Introduction: Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury started the service with a blessing of God’s love, grace and presence for all who gathered in God’s name.

Kyrie eleison: Kyrie eleison, an ancient Christian prayer, is Greek for ‘Lord, have mercy’. Sir Bryn Terfel, a Welsh bass-baritone opera singer, performed Kyrie Eleison by Paul Mealor in Welsh, composed for the coronation.

The Recognition: The Archbishop of Canterbury along with Lady Elish Frances Angiolini (a Lady of the Order of the Thistle), Christopher Finney (a holder of the George Cross for bravery under friendly fire during the 2003 invasion of Iraq) and Valerie Ann Amos, Baroness Amos (a Lady of The Garter) presented King Charles III to the East, South, West, and North sides of the coronation theater. Each person said: “I here present unto you King Charles, your undoubted King: Wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service: are you willing to do the same?” Each time, the congregation responded, “God save King Charles.”

The Presentation of the Bible: Dr. Iain Greenshields, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, presented the Bible to King Charles III saying, “Sir: to keep you ever mindful of the law and the Gospel of God as the Rule for the whole life and government of Christian Princes, receive this Book, the most valuable thing that this world affords. Here is Wisdom; This is the royal Law; These are the lively Oracles of God.”

The Oath: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Your Majesty, the Church established by law, whose settlement you will swear to maintain, is committed to the true profession of the Gospel, and, in so doing, will seek to foster an environment in which people of all faiths and beliefs may live freely. The Coronation Oath has stood for centuries and is enshrined in law. Are you willing to take the Oath?” King Charles III replied, “I am willing.” King Charles III placed his hand on the Bible, and the Archbishop administered the Oath, saying, “Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, your other Realms and the Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?” King Charles III responded, “I solemnly promise so to do.” The Archbishop said, “Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgements? King Charles III responded, “I will.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Will you to the utmost of your power to maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? Will you to the utmost of your power maintain inthe United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law? Will you maintain and preserve inviolably the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England? And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?” King Charles III responded, “All this I promise to do. The things which I have here before promised I will perform and keep. So help me God.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Your Majesty, are you willing to make, subscribe and declare to the statutory Accession Declaration Oath?” King Charles III responded, “I am willing.”

King Charles III said, “I Charles do solemnly and sincerely in the presence of God profess, testify, and declare that I am a faithful Protestant, and that I will, according to the true intent of the enactments which secure the Protestant succession to the Throne, uphold and maintain the said enactments to the best of my powers according to law.”

During the signing of the Oath, the choir sang the anthem Prevent Us, O Lord by William Byrd.

The King’s Prayer: King Charles III said, “God of compassion and mercy whose Son was sent not to be served but to serve, give grace that I may find in thy service perfect freedom and in that freedom knowledge of thy truth. Grant that I may be a blessing to all thy children, of every faith and conviction, that together we may discover the ways of gentleness and be led into the paths of peace, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

Gloria: The choir sang Gloria from Mass for Four Voices by William Byrd.

Collect: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Let us pray. Lord, enthroned in heavenly splendour: look with favour upon thy servant Charles our King, and bestow upon him such gifts of wisdom and love that we and all thy people may live in peace and prosperity and in loving service one to another, to thine eternal glory; who with the Father and the Holy Spirit reigns supreme over all things, one God, now and for ever. Amen.”

The Epistle: The Prime Minister The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP read the Epistle of St. Paul Colossians 1: 9-17: “For this cause we also, since the day we heard it, do not cease to pray for you, and to desire that ye might be filled with the knowledge of his will in all wisdom and spiritual understanding; That ye might walk worthy of the Lord unto all pleasing, being fruitful in every good work, and increasing in the knowledge of God; Strengthened with all might, according to his glorious power, unto all patience and longsuffering with joyfulness; Giving thanks unto the Father, which hath made us meet to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light: Who hath delivered us from the power of darkness, and hath translated us into the kingdom of his dear Son: In whom we have redemption through his blood, even the

forgiveness of sins: Who is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature: For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by him, and for him: And he is before all things, and by him all things consist.”

The Prime Minister: This is the word of the Lord.

Congregation: Thanks be to God.

The Ascension Gospel Choir sang Sung Alleluia Psalm 47:1-2 by Debbie Wiseman

The Gospel: Dame Sarah Mullally, Bishop of London, Dean of HM Chapels Royal read the gospel according to Luke 4:16-21: ”

Dame Sarah Mullally: The Lord be with you

Congregation: And with thy spirit.

Dame Sarah Mullally: Hear the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Luke.

Dame Sarah Mullally Glory be to thee, O Lord.

Jesus came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up: and, as his custom was, he went into the synagogue on the sabbath day, and stood up for to read. And there was delivered unto him the book of the prophet Isaiah. And when he had opened the book, he found the place where it was written, The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the broken-hearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, To preach the acceptable year of the Lord. And he closed the book, and he gave it again to the minister, and sat down. And the eyes of all them that were in the synagogue were fastened on him. And he began to say unto them, This day is this scripture fulfilled in your ears.

Dame Sarah Mullally: This is the Gospel of the Lord.

Congregation: Praise be to thee, O Christ.

The Ascension Gospel Choir sang Sung Alleluia Psalm 47:6-7 Debbie Wiseman

Sermon: Given by Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury

The choir sang Veni Creator (Come Creator Spirit), Plainsong, mode VIII

Thanksgiving for the Holy Oil: The Archbishop of Canterbury was presented with the coronation oil, by The Most Reverend Dr Hosam Naoum, The Anglican Archbishop in Jerusalem. The Archbishop said, “Blessed art thou, Sovereign God, upholding with thy grace all who are called to thy service. Thy prophets of old anointed priests and kings to serve in thy name and in the fullness of time thine only Son was anointed by the Holy Spirit to be the Christ, the Saviour and Servant of all. By the power of the same Spirit, grant that this holy oil may be for thy servant Charles a sign of joy and gladness; that as King he may know the abundance of thy grace and the power of thy mercy, and that we may be made a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for thine own possession. Blessed be God, our strength and our salvation, now and for ever. Amen.

The Anointing: During the Annointing, the choir sang Zadok the Priest by George Frederic Handel. The Anointing was done in private. The Annointing screen was arranged around the Coronation Chair where King Charles III sat. The Dean of Westminster poured oil from the ampulla into the spoon and the Archbishop of Canterbury anointed the King on hands, breast, and head, and said, “Be your hands anointed with holy oil. Be your breast anointed with holy oil. Be your head anointed with holy oil, as kings, priests, and prophets were anointed. And as Solomon was anointed king by Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet, so may you be anointed, blessed, and consecrated King over the peoples, whom the Lord your God has given you to rule and govern; in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

The clergy returned to the High Altar. The Annointing screen was removed to the St. Edward the Confessor Shrine behind the High Altar. King Charles III moved to the faldstool in front of the High Altar, and knelt. The Archbishop of Canterbury said the ‘Oil of Gladness’ prayer of blessing: “Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who by his Father was anointed with the Oil of gladness above his fellows, by his holy Anointing pour down upon your Head and Heart the blessing of the Holy Spirit, and prosper the works of your Hands: that by the assistance of his heavenly grace you may govern and preserve the People committed to your charge in wealth, peace, and godliness; and after a long and glorious course of ruling a temporal kingdom wisely, justly, and religiously, you may at last be made partaker of an eternal kingdom, through the same Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

King Charles III was vested in the Colobium Sindonis, Supertunica , and Girdle.

The Presentation of Regalia:

The Spurs: The Spurs were brought forward from the altar by the Dean of Westminster and handed to The Lord Great Chamberlain. The Lord Great Chamberlain approached The King, and presented the regalia. The King acknowledged them. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive these spurs, symbols of honour and courage. May you be a brave advocate for those in need.” The spurs were returned to the altar.

The Sword: During Exchange of Swords, a Greek choir sang Psalm 72 (Psalm 71 in the Greek Septuagint Psalter) in honor of The King’s late father The Duke of Edinburgh who was born a Prince of Greece.

The Jewelled Sword was presented to The Lord President of the Council in its scabbard and passed to the Archbishop of Canterbury who held it up before the altar. The Archbishop said, “Hear our prayers, O Lord, we beseech thee, and so direct and support thy servant King Charles, that he may not bear the Sword in vain; but may use it as the minister of God to resist evil and defend the good, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.” The Archbishop returned the sword to The Lord President and it was carried to the King. The sword was placed in the King’s right hand. The Archbishop said, “Receive this kingly Sword. May it be to you, and to all who witness these things, a sign and symbol not of judgement, but of justice; not of might, but of mercy. Trust always in the word of God, which is the sword of the Spirit, and so faithfully serve our Lord Jesus Christ in this life, that you may reign for ever with him in the life which is to come. Amen. The King stood, the sword was clipped on the girdle, and the King sat.

The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “With this sword do justice, stop the growth of iniquity, protect the holy Church of God and all people of goodwill, help and defend widows and orphans, restore the things that are gone to decay, maintain the things that are restored, punish and reform what is amiss, and confirm what is in good order: that doing these things you may be glorious in all virtue; and so faithfully serve our Lord Jesus Christ in this life, that you may reign for ever with him in the life which is to come. Amen.”

The King stood, the sword was unclipped and The King stepped forward and offered the sword to the Dean of Westminster, who placed it on the altar. The sword was redeemed from the altar by The Lord President of the Council, who placed the redemption money on the almsdish, held by the Dean of Westminster. The sword was handed to the Lord President of the Council, who carried it thereafter before The King.

The Armills: The Armills were taken from the altar and given to Lord Kamall by the Dean of Westminster. Lord Kamall approached The King, and presented the regalia. The King

acknowledged them. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive the Bracelets of sincerity and

wisdom, tokens of God’s protection embracing you on every side.” The Armills were returned to the altar.

The Robe and Stole Royal: The Prince of Wales entered the Coronation Theatre. The Stole Royal and Robe Royal were brought to The King. The Bishop of Durham vested the King in the Stole Royal. Baroness Merron with The Prince of Wales and Assisting Bishops clothed The King in the Robe. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive this Robe. May the Lord clothe you with the robe of righteousness, and with the garments of salvation.”

The Orb: The Dean of Westminster gave the Anglican Archbishop of Armagh the Orb, who brought the Orb to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who placed it in the King’s right hand.

The Archbishop said, “Receive this Orb, set under the Cross, and remember always the kingdoms of this world are become the kingdoms of our Lord, and of his Christ.” The Orb was retrieved by The Archbishop of Armagh, who gives it to the Dean, who places it back on the altar.

The Ring: The Ring was taken from the altar and given to The Lord Patel, KT, by the Dean of Westminster. Lord Patel approached The King, and presented the Ring. The King acknowledged it. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive this Ring, a symbol of kingly dignity, and a sign of the covenant sworn this day between God and King, King and people.” The Ring was returned to the altar.

The Glove: The Glove was taken from the altar and given to The Lord Singh of

Wimbledon by the Dean of Westminster. Lord Singh approached The King, and presented the ring. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive this glove. May you hold authority with gentleness and grace, trusting not in your own power but in the mercy of God who has chosen you.” The King picked up the glove and placed it on his right hand.

The Sceptre and Rod: The Sceptre and Rod were taken from the altar and given to The Archbishop of Wales and The Primus of Scotland by the Dean of Westminster. The Archbishop of Canterbury delivered them into The King’s right and left hands respectively. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive the Royal Sceptre, the ensign of kingly power and justice; and the Rod of equity and mercy, a symbol of covenant and peace. May the Spirit of the Lord which anointed Jesus at his baptism, so anoint you this day, that you might exercise authority with wisdom, and direct your counsels with grace; that by your service and ministry to all your people, justice and mercy may be seen in all the earth: through the same Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Crowning: The Dean of Westminster brought The Crown of St Edward to The Archbishop of Canterbury who said the prayer of blessing: “King of kings and Lord of lords, bless, we beseech thee, this Crown, and so sanctify thy servant Charles upon whose head this day thou dost place it for a sign of royal majesty, that he may be crowned with thy gracious favour and filled with abundant grace and all princely virtues; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who with thee and the Holy Spirit liveth and reigneth, supreme over all things, one God, world without end. Amen.

The Archbishop of Canterbury brought the crown down onto The King’s head and said, “God save The King!” The congregation said, “God save The King!”

Fanfare: The Wiener Philharmoniker Fanfare by Richard Strauss was played and the the Abbey bells rang for 2 minutes. A fanfare was sounded followed by a Gun Salute by The King’s Troop Royal Horse Artillery stationed at Horse Guards Parade. There were Gun Salutes at His Majesty’s Fortress the Tower of London fired by the Honourable Artillery Company, and at all Saluting Stations throughout the United Kingdom, Gibraltar, Bermuda, and Ships at Sea.

The Blessing: The Archbishop of York said,”The Lord bless you and keep you. The Lord make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you. The Lord lift up the light of his countenance upon you, and give you his peace.”

The Greek Orthodox Archbishop of Thyateira & Great Britain said, “The Lord protect you in all your ways and prosper all your work in his name.”

The Moderator of The Free Churches said, “The Lord give you hope and happiness, that you may inspire all your people in the imitation of his unchanging love.”

The Secretary General of Churches Together in England said, “The Lord grant that wisdom and knowledge will be the stability of your times, and the fear of the Lord your treasure.”

The Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster said, “May God pour upon you the riches of his grace, keep you in his holy fear, prepare you for a happy eternity, and receive you at the last into immortal glory.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “…and the blessing of God Almighty, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, be with you and remain with you always. Amen.”

The choir sang the anthem O Lord, grant the king a long life by Thomas Weelkes.

Enthronment The King: King Charles III was set upon the throne. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Stand firm, and hold fast from henceforth this seat of royal dignity, which is yours by the authority of Almighty God. May that same God, whose throne endures for ever, establish your throne in righteousness, that it may stand fast for evermore.”

The Homage of The Church of England: The Archbishop led the words of fealty: “I, Justin, Archbishop of Canterbury, will be faithful and true, and faith and truth will bear unto you,

our Sovereign Lord, Defender of the Faith, and unto your heirs and successors according to law. So help me God.”

The Homage of Royal Blood: The Prince of Wales led the words of fealty. “I, William, Prince of Wales, pledge my loyalty to you and faith and truth I will bear unto you, as your liege man of life and limb. So help me God.”

The Homage of The People: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “I now invite those who wish to offer their support to do so with a moment of private reflection, by joining in saying ‘God save King Charles’ at the end, or, for those with the words before them, to recite them in full.”All who so desired, in the Abbey, and elsewhere, said together: “I swear that I will pay true allegiance to Your Majesty, and to your heirs and successors according to law. So help me God.”

A fanfare is played. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “God save The King.” The congregation said, “God save King Charles. Long live King Charles. May The King live for ever.”

The choir sang the anthem Confortare by Sir Walford Davies.

The Coronation of The Queen

The Annointing: The Dean of Westminster poured oil from the ampulla into spoon, and held the spoon for the Archbishop of Canterbury. Queen Camilla was anointed on the forehead as the

Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Be your head anointed with holy oil.” The Archbishop then said, “Almighty God, the fountain of all goodness; hear our prayer this day for thy servant Camilla, whom in thy name, and with all devotion, we consecrate our Queen. Make her strong in faith and love, defend her on every side, and guide her in truth and peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Ring: The Ring was presented by The Keeper of The Jewel House to The Queen who

acknowledged it. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive this Ring, a symbol of royal

dignity, and a sign of the covenant sworn this day.” The Ring was returned to the High Altar.

The Crowning: The Dean of Westminster brought Queen Mary’s Crown from the altar and handed it to the Archbishop of Canterbury who said, “May thy servant Camilla, who wears this crown, be filled by thine abundant grace and with all princely virtues; reign in her heart, O King of love, that, being certain of thy protection, she may be crowned with thy gracious favour; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.” The Archbishop of Canterbury brought the crown down onto The Queen’s head.

The Rod and Sceptre: The Rod was presented to The Queen by The Bishop of Dover, and the Sceptre by Lord Chartres and she acknowledged them both. The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Receive the Royal Sceptre and the Rod of equity and mercy. May the Spirit guide you in wisdom and grace, that by your service and ministry justice and mercy may be seen in all the earth.”

Enthroning The Queen: Queen Camilla was set upon the throne as the choir sang the anthem Make a Joyful Noise by Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Offertory Hymn: At the start of the communion service, the choir and congregation sang the hymn Christ Is Made the Sure Foundation.

Prayer over the Gifts: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Bless, O Lord, we beseech thee, these thy gifts, and sanctify them unto this holy use, that by them we may be made partakers of the Body and Blood of thine only-begotten Son Jesus Christ, and fed unto everlasting life of soul

and body: And that thy servant King Charles may be enabled to the discharge of his weighty office, whereunto of thy great goodness thou hast called and appointed him. Grant this, O Lord, for Jesus Christ’s sake, our only Mediator and Advocate. Amen.”

The Eucharistic Prayer:

The Archbishop of Canterbury: “The Lord be with you.”

Congregation: “And with thy spirit.”

The Archbishop: “Lift up your hearts.”

Congregation: “We lift them up unto the Lord.”

The Archbishop: “Let us give thanks unto the Lord our God.”

Congregation: “It is meet and right so to do.”

The Archbishop said, “It is very meet, right, and our bounden duty, that we should at all times and in all places give thanks unto thee, O Lord, holy Father, almighty, everlasting God, through Jesus Christ thine only Son our Lord; who hast at this time consecrated thy servant Charles to be our King, that, by the anointing of thy grace, he may be the Defender of thy Faith and the Protector of thy people; that, with him, we may learn the ways of service, compassion, and love,

and that the good work which thou hast begun in him this day may be brought to completion in the day of Jesus Christ. Therefore with angels and archangels, and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious name, evermore praising thee and saying:”

Sanctus:

All sang: “Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of hosts, heaven and earth are full of thy glory. Glory be to thee, O Lord most high.”

Eucharistic Prayer continues:

The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “All glory be to thee, almighty God, our heavenly Father, who, of thy tender mercy, didst give thine only Son Jesus Christ to suffer death upon the cross for our redemption; who made there, by his one oblation of himself once offered, a full, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation and satisfaction for the sins of the whole world; and did institute, and in his holy gospel command us to continue, a perpetual memory of that his precious death, until his coming again. Hear us, O merciful Father, we most humbly beseech thee, and grant that, by the power of thy Holy Spirit, we receiving these thy creatures of bread

and wine, according to thy Son our Saviour Jesus Christ’s holy institution, in remembrance of his death and passion, may be partakers of his most blessed body and blood; who, in the same night that he was betrayed, took bread; and when he had given thanks to thee, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying: Take, eat; this is my body which is given for you; do this in remembrance of me.”

The Archbishop continued, “Likewise after supper he took the cup; and when he had given thanks to thee, he gave it to them, saying: Drink ye all of this; for this is my blood of the new covenant, which is shed for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this, as oft as ye shall drink it, in remembrance of me.

Wherefore, O Lord and heavenly Father, we thy humble servants, having in remembrance the precious death and passion of thy dear Son, his mighty resurrection and glorious ascension,

entirely desire thy fatherly goodness mercifully to accept this our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving; most humbly beseeching thee to grant that by the merits and death of thy Son Jesus Christ, and through faith in his blood, we and all thy whole Church may obtain

remission of our sins, and all other benefits of his passion. And although we be unworthy, through our manifold sins, to offer unto thee any sacrifice, yet we beseech thee to accept this our bounden duty and service, not weighing our merits, but pardoning our offences; and to grant that all we, who are partakers of this holy communion, may be fulfilled with thy grace and

heavenly benediction; through Jesus Christ our Lord, by whom, and with whom, and in whom,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit, all honour and glory be unto thee, O Father almighty, world without end. Amen.

The Lord’s Prayer: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Let us pray with confidence as our

Saviour has taught us. All say: “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done; on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation; but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory,for ever and ever. Amen.

Agnus Dei: The choir sang Agnus Dei by Tarik O’Regan during which Holy Communion is

privately received by The King an Queen.

Prayer after Communion: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “O Almighty Lord, and everlasting God, vouchsafe, we beseech thee, to direct, sanctify and govern both our hearts and bodies, in the ways of thy laws, and in the works of thy commandments; that through thy most mighty

protection,both here and ever, we may be preserved in body and soul; through our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen.”

The Final Blessing: The Archbishop of Canterbury said, “Our help is in the Name of the Lord;Who hath made heaven and earth. Blessed be the Name of the Lord; Now and henceforth, world without end. Christ our King, make you faithful and strong to do his will, that you may reign with him in glory; and the blessing of God almighty, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, rest upon you, and all whom you serve, this day, and all your days. Amen.

Sung Amen: The choir sang a Sung Amen by Orlando Gibbons.

Hymn: The choir and congregation sang Praise my Soul by Henry Francis Lyte

Anthem: The choir sang the anthem The King Shall Rejoice by William Boyce

Te Deum: The choir sang The Coronation Te Deum by Sir William Walton

The National Anthem: The choir and congregation sang the national anthem God Save The King.

The King’s Outward Procession & Organ Voluntaries: The organist played Pomp & Circumstance March no 4 by Sir Edward Elgar, arranged by Iain Farrington and March from The Birds, Sir Hubert Parry, arranged by John Rutter.

Greeting Faith Leaders & Representatives and The Governors-Generals: At the end of the procession The King received a greeting by Leaders and Representatives from Faith Communities (Jewish, Hindu, Sikh, Muslim, Buddhist). As the King stood before the Leaders

and Representatives of the Faith Communities, they delivered the following greeting in unison.

Faith Leaders & Representatives: “Your Majesty, as neighbours in faith, we acknowledge the value of public service. We unite with people of all faiths and beliefs in thanksgiving, and in service with you for the common good.” The King acknowledged the greeting, and

turned to greet the Governors-General. The King acknowledged their greeting and proceeded to the Gold State Coach.

After the Coronation

The Imperial State Crown; Credit – By Cyril Davenport (1848 – 1941) – G. Younghusband; C. Davenport (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. London: Cassell & Co. p. 6. (See also The Jewel House (1921) frontispiece.), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37624150

King Charles III and Queen Camilla proceeded to St. Edward’s Chapel, directly behind the high altar, where the Shrine of St. Edward the Confessor, King of England stands. King Charles gave St. Edward’s Crown, the Sceptre, and the Rod to the Archbishop of Canterbury who placed them on the altar in the chapel. After a short period, King Charles III emerged from St. Edward’s Chapel wearing the Imperial State Crown with the Sceptre with the Cross in his right hand and the Orb in his left hand. King Charles III and Queen Camilla, still carrying her Sceptre with the Cross in her right hand and the Ivory Rod with the Dove in her left hand, left St. Edward’s Chapel to the singing of the National Anthem and then proceeded up the aisle to the West Door of the Westminster Abbey. They returned to Buckingham Palace in the Gold State Coach using the same route as their outgoing route.

Gold State Coach; Credit – By Crochet.david (talk) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7395195

********************

Guests

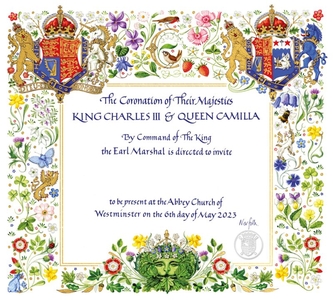

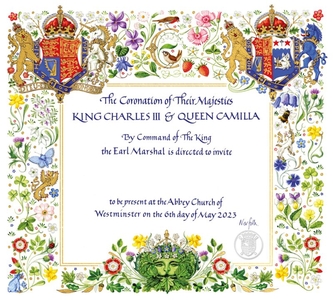

The Coronation Invitation designed by Andrew Jamieson, a heraldic artist and manuscript illuminator; Credit – Wikipedia

There were 8,000 guests at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Westminster Abbey was closed for five months prior to the coronation so that the construction needed for seating the 8,000 guests could be completed. However, because of the current safety and health regulations, Westminster Abbey’s capacity is legally approximately 2,000.

In 1953, 800 Members of Parliament and over 900 Peers were invited to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Because of the limited space, far fewer Members of Parliament and Peers were invited to the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla, causing a stir among Peers and Members of Parliament who believed they had a right to attend. Although some Members of Parliament were invited, the spouse of the British Prime Minister and the Head of Government Rishi Sunak was the only invited spouse of a Member of Parliament. The seven living past British Prime Ministers and their spouses were also invited.

450 recipients of the British Empire Medal. attended the coronation. They were invited to join the congregation at Westminster Abbey in recognition of their services and support to their local communities, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Representatives from the Commonwealth of Nations and foreign dignitaries from other countries attended. First Lady Jill Biden represented her husband Joe Biden, President of the United States.

Traditionally, foreign sovereigns have not attended British coronations. Instead, members of their royal houses were sent to represent them. King Charles III broke with that tradition, and invited foreign sovereigns, and a number of them attended. All current or former royal families who were invited sent guests except for the Kingdom of Cambodia.

The following world leaders were invited but did not attend:

- Zoran Milanović, President of Croatia was unable to attend due to a defect with the government’s plane.

- Aleksandar Vučić, President of Serbia cancelled his attendance following the Belgrade school shooting.

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, President of Turkey, declined his invitation, as he did to Elizabeth II’s funeral, due to the upcoming presidential election.

The governments of seven countries, Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, Myanmar, Russia, Syria and Venezuela, were not invited. Invitations were extended only to senior diplomats of North Korea and Nicaragua, and not their heads of state.

Note: This is a partial guest list. Links are from Unofficial Royalty or Wikipedia. Not all people listed have a link. A more complete list of guests can be seen at Wikipedia: List of guests at the coronation of Charles III and Camilla.

British Royal Family

Descendants of King Charles III

Descendants of Queen Elizabeth II

- Anne, The Princess Royal and Vice-Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence, the King’s sister and brother-in-law

- Peter Phillips, the King’s nephew

- Zara Tindall and Michael Tindall, the King’s niece and her husband

- Prince Andrew, The Duke of York, the King’s brother

- Princess Beatrice, Mrs. Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi, and Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi, the King’s niece and her husband

- Princess Eugenie, Mrs. Jack Brooksbank, and Jack Brooksbank, the King’s niece and her husband

- Prince Edward, The Duke of Edinburgh and Sophie, The Duchess of Edinburgh, the King’s brother and sister-in-law

- Lady Louise Mountbatten-Windsor, the King’s niece

- James Mountbatten-Windsor, Earl of Wessex, the King’s nephew

Descendants of King George VI

- David Armstrong-Jones, 2nd Earl of Snowdon, the King’s maternal first cousin

- Charles Armstrong-Jones, Viscount Linley, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed

- Lady Margarita Armstrong-Jones, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed

- Lady Sarah Chatto and Daniel Chatto, the King’s maternal first cousin and her husband

- Samuel Chatto, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed

- Arthur Chatto, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed

Descendants of King George V

- Prince Richard, The Duke of Gloucester and Birgitte, The Duchess of Gloucester, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed and his wife

- Alexander Windsor, Earl of Ulster, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Lady Davina Windsor, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Lady Rose Gilman, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Prince Edward, The Duke of Kent, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed

- George Windsor, Earl of St. Andrews, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Lady Helen Taylor, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Lord Nicholas Windsor, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed

- Prince Michael of Kent and Princess Michael of Kent, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed and his wife Marie-Christine

- Lord Frederick Windsor, the King’s maternal second cousin

- Lady Gabriella Kingston, the King’s maternal second cousin

Bowes-Lyon Family

- Sir Simon Bowes-Lyon and Caroline Bowes-Lyon, Lady Bowes-Lyon, the King’s maternal first cousin once removed and his wife

Mountbatten Family

Shand and Parker Bowles Families

- Brigadier Andrew Parker Bowles, the Queen’s former husband

- Thomas Parker Bowles, the Queen’s son

- Lola Parker Bowles, the Queen’s granddaughter

- Frederick Parker Bowles, the Queen’s grandson, one of the Queen’s pages of honour

- Laura Lopes and Harry Lopes, the Queen’s daughter and son-in-law

- Eliza Lopes, the Queen’s granddaughter

- Louis Lopes, the Queen’s grandson, one of the Queen’s pages of honour

- Gus Lopes, the Queen’s grandson, one of the Queen’s pages of honour

- Annabel Elliot, the Queen’s sister, one of the Queen’s two Ladies in Attendance

- Sir Benjamin Elliot and Mary-Clare Elliot, the Queen’s nephew and his wife

- Arthur Elliot, the Queen’s grandnephew, one of the Queen’s pages of honour

- Ike Elliot, the Queen’s great-nephew

- Alice and Luke Irwin, the Queen’s niece and her husband

- Otis Irwin, the Queen’s great-nephew

- Violet Irwin, the Queen’s great-niece

- Catherine Elliot, the Queen’s niece

- Ayesha Shand, the Queen’s niece, daughter of the Queen’s late brother

Middleton Family

Current Monarchies

King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia of Spain and King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium

- Sheikh Hamad bin Isa bin Salman al-Khalifa, King of Bahrain

- Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa

- King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of the Belgians, the King’s third cousin once removed and his wife

- King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck and his wife Queen Jetsun Pema of Bhutan

- Hassanal Bolkiah, Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei and a younger son Prince Abdul Mateen of Brunei

- Crown Prince Frederik and Crown Princess Mary of Denmark, the King’s third cousin once removed and his wife, representing his mother Queen Margrethe II of Denmark

- King Mswati III and his wife Inkhosikati LaMbikiza, Queen of Eswatini (formerly Swaziland)

- Crown Prince Akishino and his wife Crown Princess Kiko of Japan, representing his brother Emperor Naruhito of Japan

- King Abdullah II and his wife Queen Rania of Jordan

- Crown Prince Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah of Kuwait, representing his half-brother Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, Emir of Kuwait

- King Letsie III and his wife Queen Masenate Mohato Seeiso of Lesotho

- Hereditary Prince Alois and Hereditary Princess Sophie of Liechtenstein, the King’s fifth cousin once removed and his wife, representing his father Prince Hans-Adam of Liechtenstein

- Grand Duke Henri and Grand Duchess Maria Teresa of Luxembourg, the King’s third cousin once removed and his wife

- Al-Sultan Abdullah ibni Sultan Ahmad Shah, The Yang di Pertuan Agong and his wife Raja Permaisuri Agong of Malaysia

- Prince Albert II and Princess Charlene of Monaco, the King’s fifth cousin once removed and his wife

- Princess Lalla Meryem of Morocco, representing her brother King Mohammed VI of Morocco

- King Willem-Alexander and Queen Máxima of the Netherlands, the King’s fifth cousin and his wife

- Crown Prince Haakon and Crown Princess Mette-Marit of Norway, the King’s third cousin and his wife, representing his father King Harald V of Norway

- Crown Prince Theyazin bin Haitham Al Said of Oman, representing his father Haitham bin Tariq Al Said, Sultan of Oman

- Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, Emir of Qatar and his wife Sheikha Jawaher bint Hamad bin Suhaim Al Thani

- Prince Turki bin Mohammed Al Saud of Saudi Arabia, Minister of State, representing his uncle King Salman of Saudi Arabia

- King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia of Spain, the King’s second cousin once removed and his wife

- King Carl XVI of Sweden, the King’s third cousin once removed and his daughter Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden, the King’s fourth cousin

- King Maha Vajiralongkorn and his wife Queen Suthida of Thailand

- King Tupou VI and and his wife Queen Nanasipauʻu Tukuʻaho of Tonga

- Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi, Vice President of the United Arab Emirates, representing Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Ruler of Dubai and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates

Former Monarchies

- Bernhard, Margrave of Baden and Stephanie, Margravine of Baden, the King’s first cousin once removed and his wife

- Tsar Simeon II and Tsaritsa Margarita of Bulgaria, the King’s fourth cousin twice removed and his wife

- Queen Anne-Marie of Greece, the King’s third cousin once removed (born a Princess of Denmark) and widow of the King’s second cousin, the late King Constantine II

- Crown Prince Pavlos and Crown Princess Marie-Chantal of Greece, the King’s second cousin once removed through his father and fourth cousin through his mother, and his wife

- Donatus, Prince and Landgrave of Hesse, the King’s fourth cousin

- Philipp, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg and Princess Saskia of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the King’s first cousin once removed and his wife

- Margareta, Custodian of the Crown and Prince Radu of Romania, the King’s second cousin once removed and her husband

- Crown Prince Alexander and Crown Princess Katherine of Serbia, the King’s second cousin once removed and his wife

Ceremonial Monarchs

United Kingdom Government Officials

Prime Ministers

- Rishi Sunak, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and his wife Akshata Murty

- Sir John Major, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1990 – 1997)

- Sir Tony Blair, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1997 – 2007), and his wife Lady Blair

- Gordon Brown, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2007 – 2010), and his wife Sarah Brown

- David Cameron, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2010 – 2016), and his wife Samantha Cameron

- Theresa May, Lady May, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2016 – 2019), and her husband Sir Philip May

- Boris Johnson, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2019 – 2022), and his wife Carrie Johnson

- Liz Truss, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2022), and her husband Hugh O’Leary

Great Officers of State – England

Great Officers of State – Scotland

Officers of Arms – England

- David White, Garter Principal King of Arms

- Timothy Duke, Clarenceux King of Arms

- Robert Noel, Norroy and Ulster King of Arms

- Christopher Fletcher-Vane, Chester Herald

- Clive Cheesman, Richmond Herald

- John Allen-Petrie, Windsor Herald

- Peter O’Donaghue, York Herald

- Anne Curry, Arundel Herald Extraordinary

- John Martin Robinson, Maltravers Herald Extraordinary

- David Rankin-Hunt, Norfolk Herald Extraordinary

- Thomas Lloyd, Wales Herald Extraordinary

- Mark Scott, Bluemantle Pursuivant

- Dominic Ingram, Portcullis Pursuivant

- Adam Tuck, Rouge Dragon Pursuivant

- Thomas Johnston, Rouge Croix Pursuivant

Officers of Arms – Scotland

- Joseph Morrow, Lord Lyon King of Arms

- Adam Bruce, Marchmont Herald

- Liam Devlin, Rothesay Herald

- Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, Albany Herald Extraordinary

- George Way of Plean, Carrick Pursuivant

- John Stirling, Ormond Pursuivant

- Roderick Alexander Macpherson, Unicorn Pursuivant

- Colin Russell, Falkland Pursuivant Extraordinary

- Professor Gillian Black, Linlithgow Pursuivant Extraordinary

- Philip Tibbetts, March Pursuivant Extraordinary

Members of the Cabinet

- Oliver Dowden, Deputy Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Jeremy Hunt, Chancellor of the Exchequer

- James Cleverly, Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs

- Suella Braverman, Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Ben Wallace, Secretary of State for Defence

- Grant Shapps, Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero

- Michelle Donelan, Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology

- Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

- Steve Barclay, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

- Kemi Badenoch, Secretary of State for Business and Trade

- Thérèse Coffey, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- Mel Stride, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

- Gillian Keegan, Secretary of State for Education

- Mark Harper, Secretary of State for Transport

- Lucy Frazer, Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport

- Chris Heaton-Harris, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

- Alister Jack, Secretary of State for Scotland

- David TC Davies, Secretary of State for Wales

Leaders of Other United Kingdom Political Parties

Members of Parliament

- Sir Lindsay Hoyle, Speaker of the House of Commons and MP for Chorley

- Simon Baynes, MP for Clwyd South

- Ian Blackford, MP for Ross, Skye and Lochaber

- Andy Carter, MP for Warrington South

- Laura Farris, MP for West Berkshire

- Sarah Green, MP for Chesham and Amersham

- Mark Harper, MP for the Forest of Dean

- Richard Holden, MP for North West Durham

- Brendan O’Hara, MP for Argyll and Bute

- Kelly Tolhurst, MP for Rochester and Stroud

- Rory Stewart, former MP for Penrith and The Border, and his wife Shoshana Clark

First Ministers of Devolved Governments

- Humza Yousaf, First Minister of Scotland and Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland

- Mark Drakeford, First Minister of Wales and Keeper of the Welsh Seal

- Michelle O’Neill, First Minister-Designate of Northern Ireland

Leaders of Other Political Parties in Devolved Countries

- Jim Allister, Leader of the Traditional Unionist Voice

- Doug Beattie, Leader of the Ulster Unionist Party

- Alex Cole-Hamilton, Leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats

- Colum Eastwood, Leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party

- Naomi Long, Leader of the Alliance Party

- Douglas Ross, Leader of the Opposition in the Scottish Parliament and Leader of the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party

- Anas Sarwar, Leader of the Scottish Labour Party

Members of Devolved Parliaments

Peers of the Realm

- David Cholmondeley, 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley, Lord-in-Waiting and former Lord Great Chamberlain of England, and his wife Sarah Rose Cholmondeley, Marchioness of Cholmondeley

- Edward Stanley, 19th Earl of Derby

- James Ramsay, 17th Earl of Dalhousie, Deputy Captain General of the King’s Body Guard for Scotland

- David Ogilvy, 13th Earl of Airlie, and his wife Virginia Ogilvy, Countess of Airlie

- Patrick Stopford, 9th Earl of Courtown, Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard

- Peter St Clair-Erskine, 7th Earl of Rosslyn, Lord Steward of the Royal Household, and his wife Helen St Clair-Erskine, Countess of Rosslyn

- William Peel, 3rd Earl Peel, former Lord Chamberlain, and his wife Charlotte Peel, Countess Peel

- Rupert Ponsonby, 7th Baron de Mauley, Master of the Horse

- Jacob Rothschild, 4th Baron Rothschild

- Hugh Cavendish, Baron Cavendish of Furness, former Lord-in-Waiting, and his wife Grania Cavendish, Baroness Cavendish of Furness

- David Hope, Baron Hope of Craighead, representing the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle

- Robin Eames, Baron Eames, representing the Order of Merit

- Andrew Lloyd Webber, Baron Lloyd-Webber, composer of the coronation anthem “Make a Joyful Noise”, and his wife Madeleine Lloyd Webber, Baroness Lloyd-Webber

- Catherine Ashton, Baroness Ashton of Upholland, representing the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George

- Sebastian Coe, Baron Coe, representing the Order of Companions of Honour

- Rowan Williams, Baron Williams of Oystermouth, former Archbishop of Canterbury

- Susan Williams, Baroness Williams of Trafford, Captain of the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms

- Andrew Parker, Baron Parker of Minsmere, Lord Chamberlain

- John McFall, Baron McFall of Alcluith, Lord Speaker of the House of Lords

- Angela Smith, Baroness Smith of Basildon, Leader of the Opposition in the House of Lords

- Nicholas Soames, Baron Soames of Fletching

Other Politicians

- Hamza Taouzzale, Lord Mayor of Westminster

- Nicholas Lyons, Lord Mayor of London

- Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London

- Dan Norris, Mayor of the West of England

- Andy Street, Mayor of the West Midlands

- Tracy Brabin, Mayor of West Yorkshire

- Ben Houchen, Mayor of the Tees Valley

- Oliver Coppard, Mayor of South Yorkshire

- Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester

- Victoria Prentis, His Majesty’s Attorney General for England and Wales

Lord Lieutenants

Armed Forces

Civil Servants

- David McGill, Chief Executive of the Scottish Parliament

- Lesley Hogg, chief Executive of the Northern Ireland Assembly

- Antonia Romeo, Clerk of the Crown in Chancery in Great Britain

- Susanna McGibbon, His Majesty’s Procurator General and Solicitor for the Affairs of His Majesty’s Treasury

Representatives of Orders of Chivalry and Gallantry (Some representatives are listed elsewhere.)

Crown Dependencies

British Overseas Territories

- Dileeni Daniel-Selvaratnam, Governor of Anguilla

- Ellis Webster, Premier of Anguilla

- Paul Candler, Commissioner for the British Antarctic Territory and the British Indian Ocean Territory

- Rena Lalgie, Governor of Bermuda

- Edward David Burt, Premier of Bermuda

- Jane Owen, Governor of the Cayman Islands

- Wayne Panton, Premier of the Cayman Islands

- Alison Blake, Governor of the Falkland Islands and Commissioner of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

- Teslyn Barkman, Member of the Legislative Assembly of the Falkland Islands

- Sir David Steel, Governor of Gibraltar

- Fabian Picardo, Chief Minister of Gibraltar

- Sarah Tucker, Governor of Montserrat

- Easton Taylor-Farrell, Premier of Montserrat

- Iona Thomas, Governor of Pitcairn

- Simon Young, Mayor of Pitcairn

- Nigel Phillips, Governor of Saint Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha

- Julie Thomas, Chief Minister of Saint Helena

- James Glass, Chief Islander of Tristan da Cunha

- Anya Williams, Deputy Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands

- Charles Washington Misick, Premier of the Turks and Caicos Islands

- John Rankin, Governor of the British Virgin Islands

- Natalio Wheatley, Premier and Finance Minister of the British Virgin Islands

Commonwealth Realms

Antigua and Barbuda

- Sir Rodney Williams, Governor-General of Antigua and Barbuda, and his wife Lady Sandra Williams

- Gaston Browne, Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, and his wife Maria Bird-Browne

- Paula Frederick-Hunte, Permanent Secretary in the Office of the Governor-General

- Atlee Rodney, Commissioner of Police of the Royal Police Force of Antigua and Barbuda

- Dale Mercury, Aide-de-Camp to the Governor-General and Assistant Superintendent of Police

- Ickford Roberts, Accountant General

- Laurie Freeland Roberts, Registrar in the Civil Registry

- Bernard Warner, Field Officer at the Rehabilitation Centre for Persons with Disabilities

- Kiz Johnson, Senator, carried the flag of Antigua and Barbuda

Australia

- General David Hurley, Governor-General of Australia, and his wife Linda Hurley

- Anthony Albanese, Prime Minister of Australia, and his partner Jodie Haydon

- Margaret Beazley, Governor of New South Wales

- Linda Dessau, Governor of Victoria

- Jeannette Young, Governor of Queensland

- Christopher Dawson, Governor of Western Australia

- Frances Adamson, Governor of South Australia

- Barbara Baker, Governor of Tasmania

- Leanne Benjamin, retired Principal Dancer for the Royal Ballet

- Nicholas Cave, singer, songwriter, actor, novelist, and screenwriter

- Jasmine Coe, artist and the creator and curator of Coe Gallery

- Adam Hills, comedian, presenter, writer, and disability rights advocate

- Daniel Nour, founder of Street Side Medics

- Yasmin Poole, public speaker, board director, and youth advocate

- Emily Regan, London-based nurse who worked for the National Health Service

- Minette Salmon, studying for a PhD in Genomic Medicine and Statistics

- Claire Spencer, arts leader and the inaugural CEO of the Barbican Centre

- Merryn Voysey, Associate Professor of Statistics in Vaccinology at the Oxford Vaccine Group

- Corporal Daniel Keighran, recipient of the Victoria Cross for Australia

- Corporal Mark Donaldson, recipient of the Victoria Cross for Australia

- Warrant Officer Class Two Keith Payne, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Richard Joyes, recipient of the Australian Cross of Valour

- Yvonne Kenny, soprano

- Samantha Kerr, football (soccer) player, carried the flag of Australia

The Bahamas

- Sir Cornelius A. Smith, Governor-General of The Bahamas, and his wife Lady Smith

- Dame Marguerite Pindling, former Governor-General of The Bahamas

- Philip Davis, Prime Minister of The Bahamas, and his wife Ann Marie Davis

- Hubert Ingraham, former Prime Minister of The Bahamas

- Perry Christie, former Prime Minister of The Bahamas

- Hubert Minnis, former Prime Minister of The Bahamas

- Michael Pintard, Leader of the Opposition, and his wife Berlice Pintard

Belize

- Dame Froyla Tzalam, Governor-General of Belize, and her husband Daniel Mendez

- Francis Fonseca, Minister of Education, Culture, Science and Technology

- Cameron Gegg, finance professional, carried the flag of Belize

Canada

- Mary Simon, Governor General of Canada, and her husband Whit Fraser

- Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, and his wife Sophie Grégoire Trudeau

- Janice Charette, Clerk to the Privy Council of Canada and Secretary to the Cabinet

- RoseAnne Archibald, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations

- Natan Obed, President of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- Cassidy Caron, President of the Métis National Council

- Sarah Mazhero, member of the Prime Minister’s Youth Council

- Christina Caouette, CEO of Young Diplomats of Canada

- Rebeccah Raphael, founder of Halifax Helpers

- Marguerite Tölgyesi, President of the French-Canadian Youth Federation

- Maryam Tsegaye, winner of the Breakthrough Junior Challenge

- Jennifer Sidey-Gibbons, Canadian Space Agency astronaut

- Margaret MacMillan, member of the Order of Merit and companion of the Order of Canada

- Leslie Arthur Palmer, recipient of the Canadian Cross of Valour

- Colonel Jeremy Hansen, Canadian Space Agency astronaut, carried the flag of Canada

Grenada

- Dame Cécile La Grenade, Governor-General of Grenada

- Dickon Mitchell, Prime Minister of Grenada

- Kisha Abba Grant, High Commissioner for Grenada to the United Kingdom

- Sergeant Major Johnson Beharry, Victoria Cross recipient

- Afy Fletcher, athlete

- Lindon Victor, athlete

- Lance Sergeant Chen Charles, carried the flag of Grenada

Jamaica

- Sir Patrick Allen, Governor-General of Jamaica, and his wife Lady Patricia Allen

- David Salmon, 2023 Rhodes scholar, carried the flag of Jamaica

New Zealand

- Dame Cindy Kiro, Governor-General of New Zealand, and her husband Richard Davies

- Chris Hipkins, Prime Minister of New Zealand

- Phil Goff, High Commissioner for New Zealand to the United Kingdom

- Christopher Luxon, Leader of the Opposition

- Sir Tom Marsters, King’s Representative in the Cook Islands, and Lady Tuaine Marsters

- Richie McCaw, Order of New Zealand representative

- Willie Apiata, Victoria Cross for New Zealand representative

- Abdul Aziz, New Zealand Cross representative

- Dame Naida Glavish, former President of the Māori Party and

- Lorraine Toki, Māori advocate

- Ben Appleton, kaiāwhina and director of Ngāti Rānana

- Sarah Smart, UK general manager of The Dairy Collective

- Craig Fenton, 2023 UK New Zealander of the Year

- Rebecca Scown, former Olympic rower and CEO of Youth Experience in Sport

- Rhieve Grey, graduate student and 2021 Rhodes scholar

- Sergeant Hayden Smith, carried the flag of New Zealand

Papua New Guinea

- Sir Bob Dadae, Governor-General of Papua New Guinea, and his wife Lady Dadae

- Koni Iguan, Deputy Speaker of the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea

- Justin Tkatchenko, Minister for Foreign Affairs and his wife Savannah Tkatchenko

- Rainbo Paita, Minister for Finance and National Planning

- Taies Sansan, Secretary for the Department of Personnel Management

- Gisuwat Mangere Siniwin, former Vice Minister of Education and MP for Nawae

- Noel Leana, acting Chief of State Protocol, carried the flag of Papua New Guinea

Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Dame Marcella Liburd, Governor-General of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Terrance Drew, Prime Minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Hyleta Liburd, Deputy Governor-General for Nevis

- Mark Brantley, Premier of Nevis

- Denzil Douglas, Minister of Foreign Affairs, former Prime Minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Naeemah Hazelle, permanent secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office

- Christine Walwyn, Diaspora Ambassador

- Thouvia France, Protocol Foreign Service Officer in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Saint Lucia

Solomon Islands

- Sir David Vunagi, Governor-General of the Solomon Islands, and his wife Lady Vunagi

- Moses Kouni Mose, High Commissioner for the Solomon Islands to the United Kingdom

- Jeremiah Manele, Minister of Foreign Affairs and External Trade

Tuvalu

Other Commonwealth Countries

- Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh

- Dame Sandra Mason, President and former Governor-General of Barbados

- Mokgweetsi Masisi, President of Botswana

- Joseph Dion Ngute, Prime Minister of Cameroon, representing the President of Cameroon

- Nikos Christodoulides, President of Cyprus

- Charles Savarin, President of Dominica

- Wiliame Katonivere, President of Fiji, and First Lady Filomena Katonivere

- Ali Bongo Ondimba, President of Gabon, and First Lady Sylvia Bongo Ondimba

- Mohammed Jallow, Vice President of The Gambia

- Mamadou Tangara, Minister of Foreign Affairs of The Gambia

- Nana Akufo-Addo, President of Ghana

- Irfaan Ali, President of Guyana

- Jagdeep Dhankhar, Vice President of India, representing the President of India

- William Ruto, President of Kenya

- Lazarus Chakwera, President of Malawi

- Dato’ Zakri Jaafar, High Commissioner of Malaysia in London

- Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, President of Maldives, and First Lady Fazna Ahmed

- George Vella, President of Malta, and First Lady Miriam Vella

- Prithvirajsing Roopun, President of Mauritius

- Filipe Nyusi, President of Mozambique

- Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila, Prime Minister of Namibia

- Russ Kun, President of Nauru, and First Lady Simina Kun

- Muhammadu Buhari, President of Nigeria

- Shehbaz Sharif, Prime Minister of Pakistan

- Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda, and First Lady Jeannette Kagame

- Tuimalealiʻifano Vaʻaletoʻa Sualauvi II, O le Ao o le Malo of Samoa, and Masiofo Faʻamausili

- Leinafo

- Wavel Ramkalawan, President of Seychelles, and First Lady Linda Ramkalawan

- Julius Maada Bio, President of Sierra Leone, and First Lady Fatima Bio

- Halimah Yacob, President of Singapore

- Naledi Pandor, Minister of International Relations and Cooperation of South Africa

- Ranil Wickremesinghe, President of Sri Lanka, and First Lady Maithree Wickremesinghe

- Asha-Rose Migiro, High Commissioner of Tanzania

- Faure Gnassingbé, President of Togo

- General Jeje Odongo, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Uganda

- Hakainde Hichilema, President of Zambia, and First Lady Mutinta Hichilema

Foreign Dignitaries

Heads of State

- Bajram Begaj, President of Albania, and First Lady Armanda Begaj

- João Lourenço, President of Angola, and First Lady Ana Dias Lourenço

- Archbishop Joan Enric Vives i Sicília, Co-Prince of Andorra

- Vahagn Khachaturyan, President of Armenia

- Alexander Van der Bellen, President of Austria, and First Lady Doris Schmidauer

- Borjana Krišto, Chairwoman of the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, President of Brazil, and First Lady Rosângela Lula da Silva

- Galab Donev, Prime Minister of Bulgaria and his daughter Gabriella Doneva

- Azali Assoumani, President of Comoros, and First Lady Ambari Assoumani

- Petr Pavel, President of the Czech Republic, and First Lady Eva Pavlová

- Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, President of Djibouti

- Luis Abinader, President of the Dominican Republic, and First Lady Raquel Arbaje

- Mostafa Madbouly, Prime Minister of Egypt

- Alar Karis, President of Estonia, and First Lady Sirje Karis

- Sauli Niinistö, President of Finland, and First Lady Jenni Haukio

- Emmanuel Macron, President of France and Co-Prince of Andorra, and his wife Brigitte Macron

- Salome Zourabichvili, President of Georgia

- Frank-Walter Steinmeier, President of Germany, and First Lady Elke Büdenbender

- Katerina Sakellaropoulou, President of Greece

- Bernard Goumou, Prime Minister of Guinea

- Katalin Novák, President of Hungary, and First Gentleman István Attila Veres

- Guðni Jóhannesson, President of Iceland, and First Lady Eliza Reid

- Abdul Latif Rashid, President of Iraq

- Michael D. Higgins, President of Ireland, and his wife Sabina Higgins

- Leo Varadkar, Taoiseach of Ireland, and his partner Matthew Barrett

- Isaac Herzog, President of Israel, and First Lady Michal Herzog

- Sergio Mattarella, President of Italy, and his daughter Laura Mattarella, de facto First Lady

- Vjosa Osmani, President of Kosovo

- Egils Levits, President of Latvia, and First Lady Andra Levite

- Najib Mikati, Prime Minister of Lebanon, and his wife May Mikati

- George Weah, President of Liberia

- Mohamed al-Menfi, Chairman of the Presidential Council of Libya

- Gitanas Nausėda, President of Lithuania, and First Lady Diana Nausėdienė

- Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, President of Mauritania

- Maia Sandu, President of Moldova

- Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh, President of Mongolia, and First Lady Luvsandorjiin Bolortsetseg

- Milo Đukanović, President of Montenegro, and First Lady Lidija Đukanović

- Mohamed Bazoum, President of Niger, and First Lady Hadiza Bazoum

- Stevo Pendarovski, President of North Macedonia, and First Lady Elizabeta Gjorgievska

- Mario Abdo Benítez, President of Paraguay, and First Lady Silvana López Moreira

- Bongbong Marcos, President of the Philippines, and First Lady Liza Araneta Marcos

- Andrzej Duda, President of Poland, and First Lady Agata Kornhauser-Duda

- Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, President of Portugal

- Klaus Iohannis, President of Romania, and First Lady Carmen Iohannis

- Alessandro Scarano and Adele Tonnini, Captains Regent of San Marino

- Macky Sall, President of Senegal

- Zuzana Čaputová, President of Slovakia, and her domestic partner Juraj Rizman

- Nataša Pirc Musar, President of Slovenia, and First Gentleman Aleš Musar

- Alain Berset, President of the Swiss Confederation, and his wife Muriel Zeender

- Serdar Berdimuhamedow, President of Turkmenistan

- Denys Shmyhal, Prime Minister of Ukraine

- Võ Văn Thưởng, President of Vietnam

- Emmerson Mnangagwa, President of Zimbabwe

Governmental Representatives Representing the Head of State

- Ahmed Attaf, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Algeria

- Sahiba Gafarova, Speaker of the National Assembly of Azerbaijan

- Verónica Alcocer, First Lady of Colombia

- Álvaro Leyva, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Colombia

- Han Zheng, Vice President of the People’s Republic of China

- Christophe Mboso N’Kodia Pwanga, President of the National Assembly of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Arnoldo André, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Costa Rica

- Gordan Grlić-Radman, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Croatia

- Salvador Valdés Mesa, Vice President of Cuba

- Gustavo Manrique, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador

- Félix Ulloa, Vice President of El Salvador

- Renato Florentino, Vice President of Honduras

- Tiémoko Meyliet Koné, Vice President of Ivory Coast

- Han Duck-Soo, Prime Minister of South Korea

- Erlan Qoşanov, Head of the Majilis of the Parliament of Kazakhstan

- Yvette Sylla, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Madagascar

- Narayan Prakash Saud, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nepal

- Sayyid Badr Albusaidi, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Oman

- Janaina Tewaney, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Panama

- Aïssata Tall Sall, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Senegal

- Ivica Dačić, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Serbia

- Barnaba Marial Benjamin, Minister of Presidential Affairs of South Sudan

- Nabil Ammar, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Tunisia

- Fuat Oktay, Vice President of Turkey

- Olena Zelenska, First Lady of Ukraine

- Jill Biden, First Lady of the United States and Finnegan Biden, granddaughter of President Joe Biden

- John Kerry, Special U.S. Presidential Envoy for Climate

- Cardinal Pietro Parolin, Cardinal Secretary of State of the Vatican

- Frederick Shava, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Zimbabwe

- Mthuli Ncube, Minister of Finance of Zimbabwe

Diplomats Representing the Head of State

- Javier Esteban Figueroa, Argentinian Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Susana Herrera Quezada, Chilean Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Teferi Melesse Desta, Ethiopian Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- José Alberto Briz Gutiérrez, Guatemalan Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Euvrard Saint Amand, Haitian Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Iván Romero Martínez, Honduran Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Desra Percaya, Indonesian Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Josefa González Blanco Ortiz Mena, Mexican Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Hakim Hajoui, Moroccan Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Ahmed Albably, Consul at the Yemeni Embassy in the United Kingdom

International Organizations

Religious Leaders

Church of England