by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2019

Princess Louise of the United Kingdom and John Sutherland Campbell, then styled Marquess of Lorne, later 9th Duke of Argyll, were married at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in Windsor England on March 21, 1871.

Louise’s Early Life

Princess Louise in the 1860s; Credit – Wikipedia

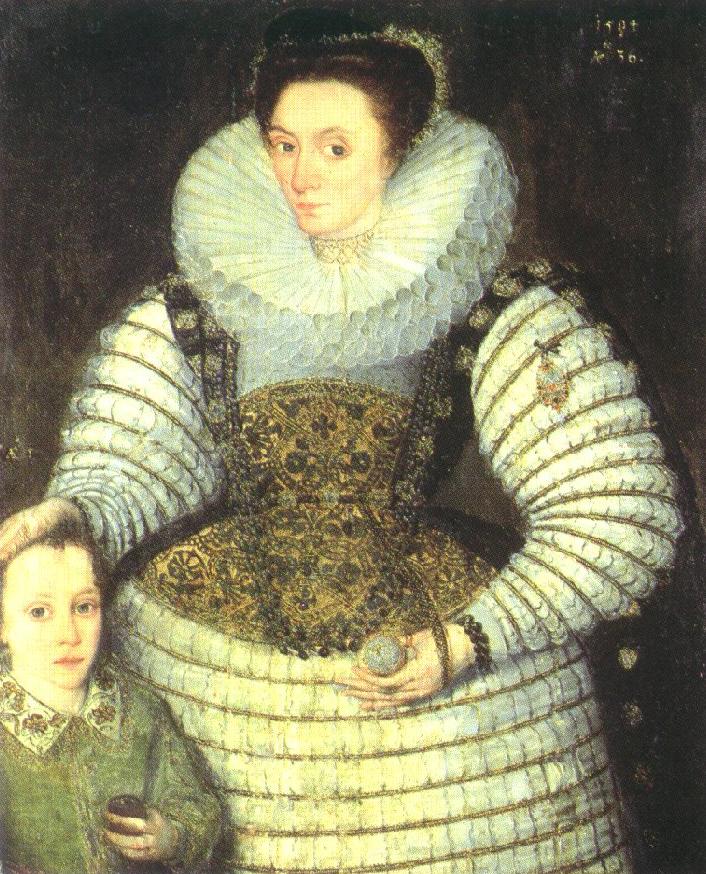

Princess Louise Caroline Alberta was born March 18, 1848, at Buckingham Palace, the fourth daughter of the five daughters and the sixth child of the nine children of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Louise was educated at home with her siblings and developed a strong interest in the arts. In 1863, Queen Victoria permitted Louise to enroll at The National Art Training School, to pursue her interests and she became a very skilled painter and sculptor. Later in life, she sculpted a statue of Queen Victoria which stands today in the grounds of Kensington Palace.

For more information on Princess Louise, see Unofficial Royalty: Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll

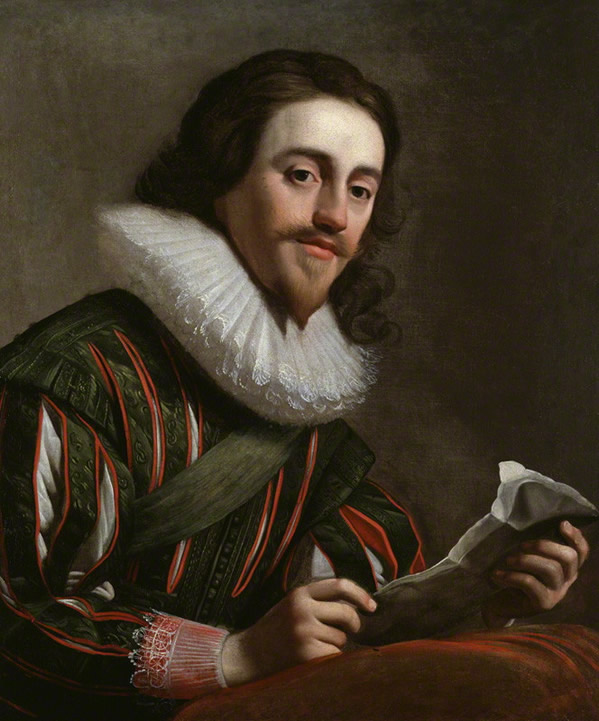

Lorne’s Early Life

Lorne with his mother; Credit – Wikipedia

John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell was born on August 6, 1845, in London, England. He was the eldest son of George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll, Head of the Highland Clan of the Campbells, and Lady Elizabeth Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, the eldest child of George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland. At the time of his birth, he was styled, by courtesy, Earl of Campbell. Less than two years later, his father succeeded his father as Duke of Argyll, and he was then styled Marquess of Lorne. He became the 9th Duke of Argyll upon his father’s death in 1900.

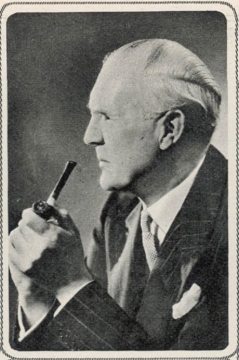

Lorne attended Edinburgh Academy, Eton College, the University of St. Andrews, and Trinity College, Cambridge. He also studied at the National Art Training School. Lorne served in the House of Commons, representing Argyllshire, Scotland from1868 – 1878 and Manchester South, England from 1895 – 1900, when he succeeded to the Dukedom of Argyll and became a member of the House of Lords. Lorne and Louise spent five years in Canada when Lorne served as Governor-General of Canada from 1878 – 1883.

For more information, see Unofficial Royalty: John Sutherland Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll

The Engagement

Louise and Lorne’s engagement photo (W & D Downey, 1870); Credit – Wikipedia

Several foreign princes were put forward as possible husbands for Louise, including the future King Frederik VIII of Denmark, Prince Albert of Prussia, and Willem, Prince of Orange, son of King Willem III of the Netherlands who ultimately predeceased his father. However, none of these princes was agreeable to Queen Victoria, and Louise herself wanted nothing to do with marriage to a prince. Queen Victoria began to pursue the idea that she could have a British son-in-law and she started a search through the noble houses and came upon the Scottish John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne and heir to the Dukedom of Argyll.

Queen Victoria met with Lorne’s father George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll about a possible marriage between their children. The duke tried to persuade Queen Victoria that at the present time, it was not a good idea. He wanted his son to marry a bit later so he could experience the life his privileged position could offer. However, the Duke of Argyll felt that any decision about marriage should be solely his son’s decision. When Queen Victoria told Louise about her meeting, she showed little interest and during 1870, several other peers and peers’ sons were paraded before Louise. Lorne felt that matters were unsettled between him and Louise and he refused to consider another possible marriage until either he or Louise definitely ended the possibility of marriage.

Meanwhile, Louise had been asking her mother if she could attend more social occasions and Queen Victoria allowed Louise to attend one of Prime Minister William Gladstone’s famous breakfast parties. By chance, Lorne was also in attendance. In the high society atmosphere and away from her mother, Louise was enchanted by the sophisticated Lorne. In 1870, Louise found herself falling in love with Lorne and he proposed to her during a walk at Balmoral, Queen Victoria’s Scottish estate, on October 3, 1870.

Although the British public loved the idea of a princess marrying a British subject, the marriage was met with much opposition in the royal family, as Lorne was not royal. There had been no marriage between a daughter of a sovereign and a British subject since 1515, when Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, married King Henry VIII’s sister Mary Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII. The Prince of Wales found it appalling that his sister should marry below her class. However, despite protests from some of Louise’s siblings as well as the Prussian court, Queen Victoria saw the marriage as an opportunity to “infuse new and healthy blood” into the royal family. The Queen offered Lorne a peerage, something she would do many times over the years, with the intent of resolving issues of precedence and giving him a rank closer to that of his wife. Lorne refused for several reasons – he would one day inherit the Argyll dukedom, and he did not want to give up his place in the House of Commons.

Wedding Site

Embed from Getty Images

St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in Windsor, England was begun in 1475 by King Edward IV and completed by King Henry VIII in 1528. It is a separate building located in the Lower Ward of Windsor Castle. The chapel seats about 800 people and has been the location of many royal ceremonies, weddings, funerals, and burials. Members of the Order of the Garter meet at Windsor Castle every June for the annual Garter Service which is held at St. George’s Chapel.

There had been no royal weddings at St. George’s Chapel until 1863 when Queen Victoria’s eldest son, the future King Edward VII, married Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Four more of Queen Victoria’s children were married there and it has become a popular site for royal weddings.

Wedding Guests

Guests Arrive At Windsor Castle To Attend The Wedding Of Princess Louise and John Campbell, Marquess of Lorne

Royal Guests

- Queen Victoria, mother of the bride

- The Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, brother of the bride

- The Princess of Wales, born Princess Alexandra of Denmark, sister-in-law of the bride

- Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia, The Princess Royal, sister of the bride

- Crown Prince Friedrich of Prussia, the future Friedrich III, German Emperor, brother-in-law of the bride

- Prince Arthur, brother of the bride

- Prince Leopold, brother of the bride

- Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (Princess Helena), sister of the bride

- Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, brother-in-law of the bride

- Princess Beatrice, sister of the bride

- Prince Albert Victor of Wales, nephew of the bride

- Prince George of Wales, the future King George V, nephew of the bride

- Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge, maternal first cousin once removed of the bride

- Duchess of Cambridge, great-aunt of the bride, born Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel

- Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, paternal uncle of the bride

- Prince Philippe of Belgium, Count of Flanders, paternal and maternal first cousin once removed of the bride

- Prince Francis of Teck and his wife, born Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, maternal first cousin once removed of the bride

- Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar

- Maharajah Duleep Singh and his wife Maharani Bamba

- Prince Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (Count of Gleichen), nephew of Queen Victoria via her half-sister Feodora of Leiningen, and his morganatic wife Laura Seymour, Countess of Gleichen

The Queen’s Household

- Anne Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, Duchess of Sutherland – Mistress of the Robes

- Susanna Innes-Ker, Duchess of Roxburghe – Lady of the Bedchamber in Waiting

- The Honorable Lucy Kerr – Maid of Honor in Waiting

- The Honorable Horatia Stopford – Maid of Honor in Waiting

- The Honorable Mrs. Alexander Gordon – Bedchamber Woman in Waiting

- John Ponsonby, 5th Earl of Bessborough – Lord Steward

- John Townshend, 3rd Viscount Sydney – Lord Chamberlain

- George Brudenell-Bruce, 2nd Marquess of Ailesbury – Master of the Horse

- Major-General Sir Thomas Biddulph – Keeper of the Privy Purse

- Colonel Henry Ponsonby – Private Secretary

- George Warren, 2nd Baron de Tabley – Treasurer of the Household

- Lord Otho Fitzgerald – Comptroller of the Household

- Valentine Browne, Viscount Castlerosse – Vice Chamberlain

- General George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan – Gold Stick in Waiting

- George Phipps, 2nd Marquess of Normanby – Captain of the Gentlemen-at-Arms

- William Beauclerk, 10th Duke of St. Albans – Captain of the Yeoman of the Guard

- Richard Boyle, 9th Earl of Cork – Master of the Buckhounds

- Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Cowell – Master of the Household

- Frederick Methuen, 2nd Baron Methuen – Lord in Waiting

- Major-General Sir Francis Seymour – Baronet, Groom in Waiting

- Lord Alfred Paget – Clerk Marshal

- Colonel C. T. Du Plat – Equerry in Waiting

- Colonel George Conyngham, Earl of Mount-Charles – Equerry in Waiting

- Mr. Henry David Erskine of Cardross – Groom of the Robes

- Colonel The Honorable Dudley de Ros – Silver Stick in Waiting

- Colonel Higginson – Field Officer in Brigade Waiting

- The Honorable Spencer Ponsonby – Comptroller in The Lord Chamberlain’s Department

- Mr. E. H. Anson – Gentleman Usher Daily Waiter

- Major-General H. F. Stephens – Senior Gentleman Usher Quarterly Waiter

- Sir Albert W. Woods – Garter King at Arms

- Mr. H Murray Lane – Chester Herald

- Mr. J. R. Planche – Somerset Herald

Representatives of Foreign Governments

- His Excellency The Turkish Ambassador

- His Excellency The Austro-Hungarian Ambassador

- His Excellency The Russian Ambassador

- The Danish Minister

- The Saxon Minister

- The Belgian Minister

- The Portuguese Minister

The Clergy

- John Jackson, Bishop of London – Dean of the Chapels Royal

- John Mackarness, Bishop of Oxford – Chancellor of the Order of the Garter

- Henry Philpott, Bishop of Worcester – Clerk of the Closet

- The Honorable Gerald Wellesley, Dean of Windsor – Lord High Almoner, Registrar of the Order of the Garter, and Domestic Chaplain

Government Officials

- William Wood, 1st Baron Hatherley – Lord High Chancellor

- Charles Wood, 1st Viscount Halifax – Lord Privy Seal

- William Ewart Gladstone – Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury

- Henry Bruce – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville – Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs

- John Wodehouse, 1st Earl of Kimberley – Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Edward Cardwell – Secretary of State for War

- George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll – Secretary of State for India, and the bridegroom’s father

- Robert Lowe – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- George Goschen – First Lord of the Admiralty

- Chichester Fortescue – President of the Board of Trade

- James Stansfeld – President of the Poor Law Board

- William Edward Forster – Vice President of the Board of Education

- William Monsell – Postmaster General

- Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Earl of Dufferin – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Acton Smee Ayrton – First Commissioner of Works

- Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Airey – Adjutant-General

- General Sir Frederick Haines – Quartermaster-General

- Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk – Earl Marshal

Household in Attendance on the Prince of Wales

- Lord Alfred Hervey – Lord of the Bedchamber in Waiting

- The Honorable C. L. Wood – Groom of the Bedchamber in Waiting

- General Sir William Knollys – Comptroller and Treasurer

- Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Ellis – Equerry in Waiting

Household in Attendance on the Princess of Wales

- George Harris, 3rd Baron Harris – Lord Chamberlain

- Fanny Osborne, Marchioness of Carmarthen – Lady of the Bedchamber in Waiting

- The Honorable Mrs. Francis Stonor – Woman of the Bedchamber in Waiting

Attendants on Other Royalty

- Count von Seckendorff – Chamberlain to Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia, The Princess Royal

- Lieutenant-Colonel Elphinstone – Governor of Prince Arthur

- Lieutenant Fitzgerald – Equerry in Attendance on Prince Arthur

- Dr. George Poore – Gentleman in Attendance on Prince Leopold

- Mr. R. W. Collins – Gentleman in Attendance on Prince Leopold

- Lieutenant-Colonel G. G. Gordon – Treasurer to Prince and Princess Christian (Helena)

- Lady Susan Leslie-Melville – Lady in Attendance on Princess Christian

- Mrs. G. G. Gordon – Lady in Attendance on Princess Christian

- Lady Caroline Barrington – Lady in Attendance on Princess Beatrice

- Colonel Clifton – Gentleman in Attendance on The Duchess of Cambridge

- Lady Geraldine Somerset – Lady in Attendance on The Duchess of Cambridge

- Colonel Tyrwhitt – Equerry in Waiting on The Duke of Cambridge

- Colonel Airey – Gentleman in Attendance on The Prince and Princess of Teck

- Lady Caroline Cust – Lady in Attendance on The Princess of Teck

- Colonel Oliphant – Gentleman in Attendance on The Maharajah and the Maharani

- Major Von Schrabisch – Gentleman in Attendance on The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

- Lieutenant Von Zigesar – Gentleman in Attendance on The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

- Lieutenant-Colonel Burnell – Aide-de-Camp to The Count of Flanders

Invited Guests

(Some spouses are not listed here because they were in attendance or on duty during the wedding.)

- George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll and Elizabeth Campbell, Duchess of Argyll, parents of the bridegroom

- Anne Campbell, Dowager Duchess of Argyll, paternal step-grandmother of the groom

- Edith Percy, Countess Percy, sister of the groom and wife of Henry Percy, Earl Percy, who was one of the groom’s supporters

- Lord and Lady Archibald Campbell, brother of the groom and his wife

- Lord Colin Campbell, brother of the groom

- Lady Victoria Campbell – sister of the groom

- Lady Evelyn Campbell – sister of the groom

- Lady Frances Campbell – sister of the groom

- Lady Mary Campbell – sister of the groom

- Lady Constance Campbell – sister of the groom

- Hugh Grosvenor, 3rd Marquess of Westminster and Constance Grosvenor, Marchioness of Westminster, maternal aunt of the bridegroom and her husband

- Lord Albert Levenson-Gower, maternal uncle of the groom

- Charles Stuart, 12th Lord Blantyre, brother-in-law of the groom and his daughters The Honorable Miss Stuarts, nieces of the groom

- Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Offaly, maternal first cousin of the groom

- Victor Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor – first cousin of the groom

- Lady Florence Leveson-Gower – first cousin of the groom

- Lady Elizabeth Grosvenor – first cousin of the groom

- Lady Beatrice Grosvenor – first cousin of the groom

- Charles Gordon-Lennox, 6th Duke of Richmond and Frances Gordon-Lennox, Duchess of Richmond

- Sybil Beauclerk, Duchess of St. Albans

- James Innes-Ker, 6th Duke of Roxburghe

- Arthur Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington and Elizabeth Wellesley, Duchess of Wellington

- Francis Seymour, 5th Marquess of Hertford, Emily Seymour, Marchioness of Hertford, and Lady Florence Seymour

- Jane Loftus, Marchioness of Ely

- Mary Brudenell-Bruce, Marchioness of Ailesbury

- Elizabeth Butler, Marchioness of Ormonde

- Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby and Mary Stanley, Countess of Derby

- John Montagu, 7th Earl of Sandwich and Mary Montagu, Countess of Sandwich

- Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

- Frances Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough

- Castila Rosalind Levenson-Gower, Countess Granville

- George Byng, 7th Viscount Torrington

- Alexander Hood, 1st Viscount Bridport, Mary Hood, Viscountess Hood, and The Honorable Miss Hood

- Mary Disraeli, Viscountess Beaconsfield and Benjamin Disraeli

- Francis Leveson-Gower, Viscount Tarbat

- Emily Townshend, Viscountess Sydney

- Eliza Agar-Ellis, Viscountess Clifden

- Sir David Baird, 3rd Baronet

- Sir Donald Campbell, 3rd Baronet of Dunstaffnage

- Sir William Jenner, 1st Baronet – Physician in Ordinary to Queen Victoria

- Lady Arthur Lennox

- Lady Wriothesley Russell

- Lady Edward Cavendish

- The Honorable Miss and Miss B. Lascelles

- The Honorable C. Howard

- The Honorable H. Howard

- Major-General The Honorable Alexander Gordon

- Reverend The Honorable Francis Grey and Lady Elizabeth Grey

- Captain The Honorable Charles Eliot

- The Honorable F. Wood

- Colonel The Honorable G. Augustus Liddell

- The Honorable Mrs. Wellesley

- The Honorable Eva Macdonald

- The Honorable Lady Biddulph

- Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Dean of Westminster and Lady Augusta Stanley

- Sir John and Lady Clark

- Lady Cowell

- Monsieur Jean-Sylvain, former Prime Minister of Belgium and Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Madame Van de Weyer and Miss Van de Weyer

- Mrs. Gladstone – wife of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone

- Mr. Frederick Gibbs – former tutor to The Prince of Wales and Prince Alfred

- Mr. Campbell of Islay – Scottish author and scholar who specialized in Celtic studies

- Mr. Colin Campbell of Stonefield

- Mr. and Mrs. William Russell

- Lieutenant-Colonel George Ashley Maude, Crown Equerry of the Royal Mews

- Mademoiselle Raluka Musurus, Greek pianist

- Reverend Canon Henry Mildred Birch, Chaplain to The Prince of Wales

- Reverend James St. John Blunt, Chaplain-in-Ordinary to Queen

- Reverend Robinson Duckworth, tutor to Prince Leopold

- Reverend Henry Ellison, Chaplain-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria

- Reverend Dr. Thomas Guthrie – Scottish minister and social reformer

- Reverend N. Macpherson

- Reverend William Lake Onslow – special naval instructor to Prince Alfred

- Reverend Canon George Prothero, Chaplain-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria, Rector of St. Mildred’s Church, Whippingham, Isle of Wight, where Queen Victoria’s family worshipped when at Osborne House

- Reverend W. Story

- Reverend C. F. Tarver – former tutor to The Prince of Wales

- Reverend Dr. Taylor

- Reverend Principal John Tulloch – Scottish theologian

- Mr. Hermann Sahl, Librarian and German Secretary to Queen Victoria

- Mr. Holmes

- Mr. Arthur Helps – Clerk of the Privy Council

- Mr. Theodore Martin – Scottish poet, biographer, and translator.

- Mr. Quintin Hogg – football (player) and philanthropist

- Mr. Francis Knollys – Private Secretary to The Prince of Wales

- Mr. M. Holzmann

- Mr. Herbert Fisher

- Dr. Douglas Argyll Robertson – Surgeon Oculist to Queen Victoria

- Dr. William Marshall – Resident Physician to Queen Victoria

- Dr. William Carter Hoffmeister – Surgeon to Queen Victoria

- Miss Ottilie Bauer, German tutor to Queen Victoria’s children

- Mademoiselle Norelle – French tutor to Queen Victoria’s children

- Madame Dalmas

- Miss Sarah Anne Hildyard – tutor to Queen Victoria’s children

- Dr. James Ellison – Apothecary to Queen Victoria

- Dr. Thomas Fairbank – Apothecary to Queen Victoria

- Mr. Meyer

- Mrs. Lucy Anderson – piano teacher to Queen Victoria and her family

- Mr. Edward Corbould – instructor of historical painting to Queen Victoria and her family

- Mr. Evans, Junior

- Mr. Brasseur – former French tutor to The Prince of Wales

Bridesmaids and Supporters

Princess Louise was supported by her mother Queen Victoria, her eldest brother The Prince of Wales and her paternal uncle Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Jane Spencer, Baroness Churchill, Lady of the Bedchamber to the Queen, was in attendance on Princess Louise.

There were eight bridesmaids, all unmarried daughters of Dukes, Marquesses, or Earls.

- Lady Mary Butler, daughter of John Butler, 2nd Marquess of Ormonde, married The Honorable William Henry Fitzwilliam

- Lady Elizabeth Campbell, sister of the groom, daughter of George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll, married Lt.-Col. Edward Harrison Clough-Taylor

- Lady Mary Cecil, daughter of James Gascoyne-Cecil, 2nd Marquess of Salisbury, married Alan Stewart, 10th Earl of Galloway

- Lady Alice FitzGerald, daughter of Charles FitzGerald, 4th Duke of Leinster, married Sir Charles John Oswald FitzGerald

- Lady Grace Gordon, daughter of Charles Gordon, 10th Marquess of Huntly, married Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale

- Lady Florence Gordon-Lennox, daughter of Charles Gordon-Lennox, 6th Duke of Richmond, unmarried

- Lady Florence Montagu, daughter of John Montagu, 7th Earl of Sandwich, married Alfred Charles Duncombe

- Lady Constance Seymour, daughter of Francis Seymour, 5th Marquess of Hertford, married Frederick St John Newdigate Barne

The supporters for the bridegroom were Henry Percy, Earl Percy and Lord Ronald Sutherland-Leveson-Gower. Henry Percy was styled Earl Percy, one of the subsidiary titles of his father Algernon Percy, 6th Duke of Northumberland. He was the groom’s brother-in-law, the husband of the groom’s eldest sister, and later was the 7th Duke of Northumberland. Lord Ronald was the youngest of the four sons and the tenth of the eleven children of George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland. His eldest sister was the groom’s mother and so Lord Ronald was the groom’s maternal uncle. He was the same age as the groom so he was more a friend than an uncle.

Wedding Attire

Princess Louise in her wedding dress; Credit – Wikipedia

Louise wore a white silk wedding gown with deep flounces of flower-strewn Honiton lace. The dress was trimmed with orange blossoms, white heather, and myrtle and had a train that corresponded with the rest of the dress. On her head, Louise wore a wreath of orange blossoms and myrtle with a short wedding veil of Honiton lace that she designed herself. Her veil was held in place by two of the three diamond daisy brooches given to her by her three youngest siblings Prince Arthur, Prince Leopold, and Princess Beatrice. The diamond daisy brooches are now the property of Princess Michael of Kent, whose husband had been willed them from his mother Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent. Princess Louise liked her great-nephew Prince George, Duke of Kent and his wife Princess Marina. When Louise died in 1939, she left several pieces of jewelry to Marina including the diamond daisy brooches. You can see and read more about the daisy brooches here: Artemisia’s Royal Jewels: Focus on… Kent Jewels: The Argyll Daisy Brooches.

Louise received a beautiful bracelet from her future husband. The center, with a sapphire mounted with diamonds and pearls and a pearl drop, could be worn as a pendant ornament. Princess Louise wore this pendant on a diamond necklace on her wedding day, and it can be seen in her wedding photographs. She also wore an emerald bracelet given to her by the Prince and Princess of Wales and a diamond bracelet that had been given to her maternal grandmother, the Duchess of Kent, born Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, by the people of Windsor.

While Lorne’s male kinsmen wore kilts of the Campbell tartan, he wore the uniform of the Royal Argyllshire Artillery Volunteers.

The bridesmaids’ dresses were of white glacé-silk, trimmed with satin, with a tunic of gossamer and fringe, decorated with cerise roses, white heather, and sand ivy. On their heads, they wore corresponding floral wreaths. Each of the bridesmaids wore a locket made from cristal de roche, richly decorated with blue and white enamel. In the center of the locket was a purple scroll inscribed with “Louise 1871” surrounded by a wreath of roses and forget-me-nots. The loop was formed of a Princess’ coronet studded with emeralds and rubies attached to a true lover’s knot of turquoise enamel suspended from a gold chain.

Wedding

Embed from Getty Images

Guests arrived by a special train from London and were met at the Windsor train station by carriages which took them to the entrance of St. George’s Chapel near Wolsey Chapel, now known as the Albert Memorial Chapel, and they were then shown to their seats. The groom’s parents, the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, and other close relatives of the groom arrived from Windsor Castle and were taken to their seats near the altar. Next, the clergy participating in the wedding ceremony took their places at the altar.

Members of the British royal family and other royalty assembled in the Green Drawing Room of Windsor Castle. At twelve noon, the royalty along with their attendants were taken by carriages to the south entrance of St. George’s Chapel. They proceeded up the nave to their seats in the choir while The Festal March composed especially for Princess Louise’s wedding by the St. George’s Chapel organist George Elvey was played on the organ.

The bridegroom arrived from Windsor Castle with his two supporters and was shown into the Bray Chapel. After all the royalty was seated, Lorne was escorted to his place near the altar, accompanied by his two supporters. As he proceeded to his place, the March from George Fredrich Handel’s oratorio Joseph was played on the organ. Meanwhile, the bridesmaids assembled at the West Door to St. George’s Chapel where they waited in a room for the arrival of the bride.

At 12:15 PM, Princess Louise, accompanied by her supporters, her mother Queen Victoria, her brother the Prince of Wales, and her paternal uncle Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, along with their respective attendants, left Windsor Castle in carriages for the short ride to the West Door of St. George’s Chapel. The bridal procession formed at the West Door and proceeded through the nave to the choir while Felix Mendelssohn’s March from Athalie was played on the organ. The bride was supported by Queen Victoria on her right and the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on the left.

Queen Victoria, who gave her daughter away, was seated near the bride as were the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The wedding ceremony was performed by John Jackson, Bishop of London in the absence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. During the ceremony, the choir sang two psalms composed by George Elvey and a chorus by Ludwig von Beethoven.

At the conclusion of the wedding ceremony, a royal salute was fired. The newlyweds and the royalty left St. George’s Chapel via the West Door as the organ played the March from Occasional Oratorio by George Friedrich Handel.

Post-Wedding

Upon returning to Windsor Castle, the marriage registry was signed by the bride and groom, Queen Victoria, and other royalty and members of the government in the White Drawing Room. A private luncheon was served to the royalty in the Oak Room while a buffet luncheon for the other guests was served in the Waterloo Gallery.

The wedding cake was quite spectacular. It stood five feet high and weighed over 225 pounds. The cake had four tiers and was shaped like a tower. Atop the cake was a classical female figure. Cherubs, flowers, vases, Greek Corinthian columns, and other figures decorated the cake which was finished with fine white icing. Queen Victoria’s chief confectioner Samuel Ponder worked on the cake for three months.

At 3:30 PM, a special train left Windsor, taking the guests back to London. The newlyweds left Windsor Castle at 4:00 PM, attended by Jane Spencer, Baroness Churchill, a Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Victoria, and Colonel George Conyngham, Earl of Mount-Charles, Equerry in Waiting to Queen Victoria, for a four-day honeymoon at Claremont House in Esher in Surrey, England.

Later in the evening, a banquet was held in the Waterloo Chamber and then an evening party was held in St. George’s Hall.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Artemisiasroyaljewels.blogspot.com. (2013). Focus on… Kent Jewels: The Argyll Daisy Brooch. [online] Available at: http://artemisiasroyaljewels.blogspot.com/2013/02/british-royal-jewels-kent-jewels-argyll.html [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Britten, Nick. (2009). Royal wedding cake from 1871 goes on sale. [online] Telegraph.co.uk. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/theroyalfamily/5158418/Royal-wedding-cake-from-1871-goes-on-sale.html [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Wedding Dress of Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wedding_dress_of_Princess_Louise,_Duchess_of_Argyll [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Google Books. (1871). Bulletins and Other State Intelligence – Ceremonial observed at the marriage of Her Royal Highness The Princess Louise and John Douglas Sutherland, Marquis of Lorne. [online] Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=V3ouAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA252&lpg=PA252&dq=London+Gazette+Marriage+of+Princess+Louise+21+March+1871&source=bl&ots=rWX5fibV05&sig=ACfU3U3N_Zq-sJmrJ9C6GSKdyc9vzuNFbA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwja34aF75nkAhUOVd8KHf4QD9EQ6AEwC3oECB0QAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Hawksley, L. (2017). Queen Victoria’s Mysterious Daughter. New York, N.Y.: Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin’s Griffin.

- Mehl, Scott. (2015). John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/john-campbell-9th-duke-of-argyll/ [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Mehl, Scott. (2014). Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/march-18-1948-birth-of-the-princess-louise-duchess-of-argyll/ [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Packard, Jerrold. (1998). Victoria’s Daughters. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- The Royal Family. (2019). The History of Royal Wedding Cakes. [online] Available at: https://www.royal.uk/royal-wedding-cakes-history [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Trove. (1871). MARRIAGE OF THE PRINCESS LOUISE AND THE MARQUIS OF LORNE. – Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser (Vic. : 1842 – 1843; 1854 – 1876) – 18 May 1871. [online] Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/65424977 [Accessed 8 Sep. 2019].

- Van der Kiste, J. (2011). Queen Victoria’s Children. Stroud: The History Press.