by Scott Mehl

© Unofficial Royalty 2019

The Coronet of a Marquess. photo: By SodacanThis W3C-unspecified vector image was created with Inkscape. – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10963961

Marquess is the second-highest title in the British peerage, holding precedence following Dukes, in order of creation. Currently, there are 55 Marquessates, held by 51 people. For 34 of them, Marquess is their senior title, while the others are subsidiary titles of Dukes.

The word Marquess comes from the french marchis, mean ruler of a border area. Marchis was itself derived from marche – “frontier”, coming from the Latin marcha. Women holding a Marquessate in their own right and wives of a Marquess hold the title Marchioness.

The title of Marquess was first used in England in 1385, when Robert de Vere, the 9th Earl of Oxford was created Marquess of Dublin by King Richard II. Less than a year later, the title was revoked, and de Vere was created Duke of Ireland. In 1397, two additional marquessates – Dorset and Somerset – were granted to John Beaufort, the 1st Earl of somerset. These, two, were revoked two years later. It would be 1442 before the title of Marquess was granted again, and continued so until the 1930s. In total, 135 Marquessates have been created, consisting of 125 different titles. These include 1 woman created a Marchioness in her own right (a title which went extinct upon her death).

The Peerage of England (1385-1707)

- 33 Marquessates created

- 30 different titles

- 1 Marchioness in her own right

- 6 still extant

The Peerage of Scotland (1488-1707)

- 23 Marquessates created

- 22 different titles

- 13 still extant

The Peerage of Great Britain (1707-1801)

- 22 Marquessates created

- 22 different titles

- 8 still extant

The Peerage of Ireland (1642-1801-1825)

- 24 Marquessates created

- 19 different titles

- 10 still extant

The Peerage of the United Kingdom (1801-present)

- 33 Marquessates created

- 32 different titles

- 18 still extant

The most senior Marquess, known as The Premier Marquess of England, is the Marquess of Winchester whose title was created in 1551. He is also the only Marquess in the Peerage of England with no higher ranking Dukedom.

The last non-Royal Marquessate – Marquess of Willingdon – was granted in 1936. However, it became extinct in 1979. The last created, and still extant, is the Marquess of Reading, created in 1926.

Frederick, Prince of Wales. source: Wikipedia

The last Royal Marquessates were granted in 1726 by King George II to two of his sons:

- Prince Frederick was created Duke of Edinburgh, Marquess of the Isle of Ely, Earl of Eltham, Viscount Launceston and Snowdon. Frederick later became Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay, and was the father of King George III. His titles passed to his son, and reverted to the crown upon his accession in 1760.

- Prince William was created Duke of Cumberland, Marquess of Berkhamsted, Earl of Kennington, Viscount Trematon and Baron Alderney. These titles became extinct upon his death in 1765.

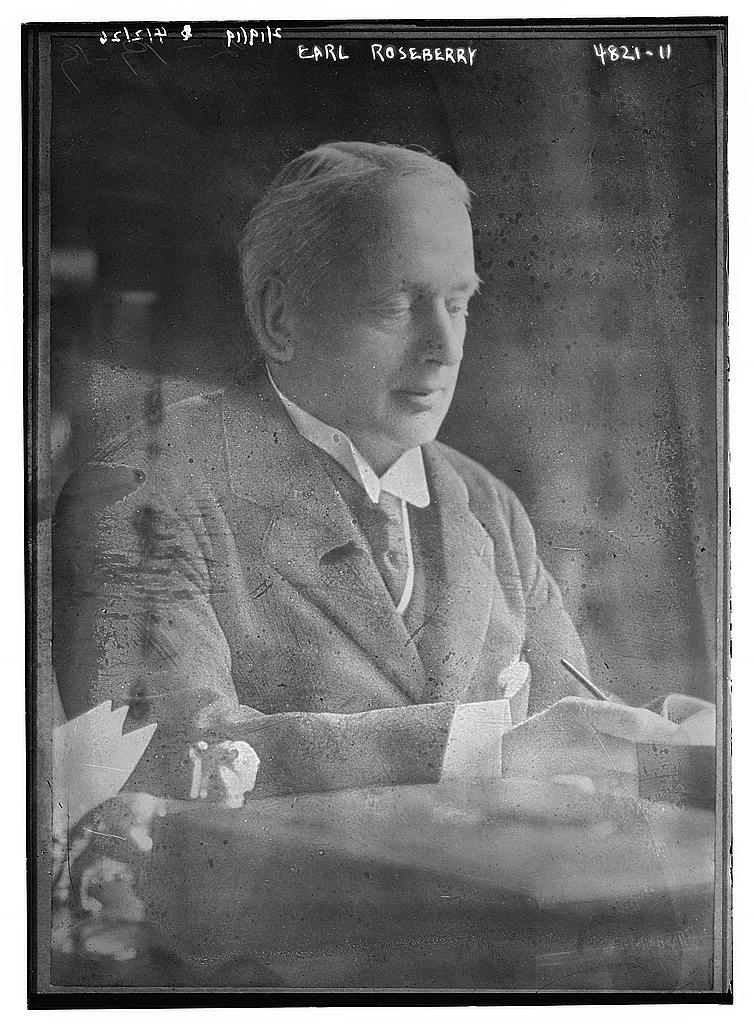

The Marquess of Milford Haven, formerly Prince Louis of Battenberg. source: Wikipedia

In addition, three Marquessates were created for relatives of the Royal Family in November 1917, when King George V asked his relatives to relinquish their German titles and styles:

- Prince Adolphus of Teck, The Duke of Teck – became Adolphus Cambridge, was created Marquess of Cambridge, Earl of Eltham and Viscount Northallerton

- Prince Louis of Battenberg – became Louis Mountbatten, was created Marquess of Milford Haven, Earl of Medina and Viscount Alderney

- Prince Alexander of Battenberg – became Alexander Mountbatten, created Marquess of Carisbrooke, Earl of Berkhamsted and Viscount Launceston

Anne Boleyn, Queen of England. source: Wikipedia

There has only been one woman created a Marchioness in her own right:

Anne Boleyn (c1501-1536) – in preparation for her wedding to King Henry VIII, she was created Marchioness of Pembroke in her own right in an investiture ceremony held at Windsor Castle on September 1, 1532. The couple married several months later, and Anne was Queen of England until her beheading in 1536. The title was created with remainder to her “heirs male”, making it the first hereditary peerage granted to a woman. However, as she had no sons, the title became extinct upon her death.

Styles and Titles

- A Marquess is styled The Most Honourable The Marquess of XX, and referred to as ‘My Lord’ or ‘Your Lordship’.

- A Marchioness is styled The Most Honourable The Marchioness of XX, and referred to as ‘My Lady’ or ‘Your Ladyship’.

- The eldest son of a Marquess traditionally uses his father’s most senior, but lower-ranking, subsidiary title as a courtesy title. (If the senior subsidiary title is similar to the name of the Marquessate, the next senior title is used). This is used without the article ‘The’ preceding it. For example, the eldest son of the Marquess of Milford Haven is styled ‘Earl of Medina’.

- Younger sons and all daughters of a Marquess are styled as ‘Lord/Lady (first name) (surname)’. Example: Lady Tatiana Mountbatten is the daughter of The Marquess of Milford Haven.

LIST OF EXTANT DUKEDOMS, in order of creation:

PEERAGE OF ENGLAND

Marquess of Winchester

Marquess of Worcester – subsidiary title of the Duke of Beaufort

Marquess of Tavistock – subsidiary title of the Duke of Bedford

Marquess of Hartington – subsidiary title of the Duke of Devonshire

Marquess of Blandford – subsidiary title of the Duke of Marlborough

Marquess of Granby – subsidiary title of the Duke of Rutland

PEERAGE OF SCOTLAND

Marquess of Huntly

Marquess of Douglas – subsidiary title of the Duke of Hamilton and Brandon

Marquess of Clydesdale – subsidiary title of the Duke of Hamilton and Brandon

Marquess of Montrose – subsidiary title of the Duke of Montrose

Marquess of Atholl – subsidiary title of the Duke of Atholl

Marquess of Queensberry

Marquess of Dumfriesshire – subsidiary title of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry

Marquess of Tweeddale

Marquess of Kintyre and Lorne – subsidiary title of the Duke of Argyll

Marquess of Lothian

Marquess of Tullibardine – subsidiary title of the Duke of Atholl

Marquess of Graham and Buchanan – subsidiary title of the Duke of Montrose

Marquess of Bowmont and Cessford – subsidiary title of the Duke of Roxburghe

PEERAGE OF GREAT BRITAIN

Marquess of Lansdowne

Marquess of Stafford – subsidiary title of the Duke of Sutherland

Marquess Townshend

Marquess of Salisbury

Marquess of Bath

Marquess of Abercorn – subsidiary title of the Duke of Abercorn

Marquess of Hertford

Marquess of Bute

PEERAGE OF IRELAND

Marquess of Kildare – subsidiary title of the Duke of Leinster

Marquess of Waterford

Marquess of Downshire

Marquess of Donegall

Marquess of Headfort

Marquess of Sligo

Marquess of Ely

Marquess of Londonderry

Marquess Conyngham

Marquess of Hamilton – subsidiary title of the Duke of Abercorn

PEERAGE OF THE UNITED KINGDOM

Marquess of Exeter

Marquess of Northampton

Marquess Camden

Marquess of Wellington – subsidiary title of the Duke of Wellington

Marquess Douro – subsidiary title of the Duke of Wellington

Marquess of Anglesey

Marquess of Cholmondeley

Marquess of Ailesbury

Marquess of Bristol

Marquess of Ailsa

Marquess of Westminster – subsidiary title of the Duke of Westminster

Marquess of Normanby

Marquess of Abergavenny

Marquess of Zetland

Marquess of Linlithgow

Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair

Marquess of Milford Haven

Marquess of Reading

Multiple Marquessate Holders

The Duke of Abercorn holds the Marquessates of Abercorn and Hamilton

The Duke of Atholl holds the Marquessates of Atholl and Tullibardine

The Duke of Hamilton and Brandon holds the Marquessates of Douglas and Clydesdale

The Duke of Wellington holds the Marquessates of Wellington and Douro

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.