by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2023

Maria Amalia of Saxony, Queen of Spain, Queen of Naples & Sicily; Credit – Wikipedia

Maria Amalia of Saxony was the wife of King Carlos III of Spain who also was King Carlo VII of Naples from 1735 – 1759 and King Carlo V of Sicily from 1734 – 1759. Born on November 24, 1724, at Dresden Castle, in Dresden, Electorate of Saxony, now in the German state of Saxony, Maria Amalia Christina Franziska Xaveria Flora Walburga was a Princess of Poland and a Princess of Saxony. She was the fourth of the fourteen children and the eldest of the seven daughters of Augustus III, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, who was also Friedrich August II, Elector of Saxony, and Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria. Maria Amalia’s paternal grandparents were Augustus II, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, who was also Friedrich August I, Elector of Saxony, and Christiane Eberhardine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth. Her maternal grandparents were Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I and Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick -Lüneburg.

Maria Amalia had thirteen siblings:

- Friedrich August of Saxony (1720 – 1721), died in infancy

- Joseph August of Saxony (1721 – 1728), died in childhood

- Friedrich Christian, Elector of Saxony (1722 – 1763), married Maria Antonia of Bavaria, had eight children

- Maria Margaretha of Saxony (1727 – 1734), died in childhood

- Maria Anna Sophie of Saxony (1728 – 1797), married Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria, no children

- Franz Xavier, Regent of Saxony (1730 – 1806), married morganatically Maria Chiara Spinucci, had ten children known as Counts and Countesses of Lusatia

- Maria Josepha of Saxony (1731 – 1767), married Louis, Dauphin of France, son of King Louis XV of France, had eight children including three Kings of France: Louis XVI, Louis XVIII, and Charles X

- Karl Christian of Saxony (1733 – 1796), married Countess Franciszka Krasińska, had two children

- Maria Christina of Saxony, Princess-Abbess of Remiremont (1735 – 1782), unmarried

- Maria Elisabeth Apollonia of Saxony (1736 – 1818), unmarried

- Albrecht Kasimir of Saxony, Duke of Teschen and Governor of the Austrian Netherlands (1738 – 1822), married Archduchess Maria Christina of Austria, had one daughter who lived for one day

- Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony, Archbishop of Trier (1739 – 1812), unmarried

- Maria Kunigunde of Saxony, Princess-Abbess of Thorn and Essen (1740 – 1826), unmarried

Dresden Castle where Maria Amalia was born and raised; Credit – By X-Weinzar – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7530258

Maria Amalia was raised at her father’s court at Dresden Castle in Dresden, Electorate of Saxony, now in the German state of Saxony. She received instruction in foreign languages, mathematics, foreign cultures, theater, and dancing. Maria Amalia was also an excellent musician and sang and played the piano from an early age.

Maria Amalia’s husband Carlos as King of Naples and Sicily; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1738, a marriage was arranged for fourteen-year-old Maria Amalia and twenty-two-year-old Carlos of Spain, then sovereign of two Italian kingdoms as King Carlo VII of Naples and King Carlo V of Sicily. Carlos was the eldest son of Felipe V, the first Bourbon King of Spain and his second wife Elisabeth Farnese of Parma, who had arranged the marriage. Carlos was not expected to become King of Spain because he had two elder surviving brothers from his father’s first marriage to Maria Luisa of Savoy.

On May 8, 1738, a proxy marriage was held in Dresden, Electorate of Saxony, now in Germany with the bride’s brother Friedrich Christian of Saxony standing in for Carlos. Shortly afterward, Maria Amalia traveled to the Kingdom of Naples, and on June 19, 1738, at Portella, a village on the border of the Kingdom of Naples, Carlos and Maria Amalia met for the first time and were married.

Three children of Maria Amalia and Carlos: Francisco Javier, Maria Luisa, and Carlos III’s successor, the future King Carlos IV; Credit – Wikipedia

Maria Amalia and Carlos had thirteen children but only seven survived childhood. Their children who were born before Carlos became King of Spain were Princes and Princesses of Naples and Sicily. Their children who survived until Carlos became King of Spain were then Infantes and Infantas of Spain.

- Princess Maria Isabel of Naples and Sicily (1740 – 1742), died in early childhood

- Princess Maria Josefa of Naples and Sicily (born and died 1742), died in infancy

- Princess Maria Isabel Ana of Naples and Sicily (1743 – 1749), died in childhood

- Infanta Maria Josefa of Spain (1744 – 1801), unmarried

- Infanta Maria Luisa of Spain (1745 – 1792), married Pietro Leopoldo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany, later Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, had sixteen children

- Infante Felipe of Spain, Duke of Calabria (1747 – 1777), unmarried, excluded from the succession due to learning disabilities and epilepsy, died from smallpox

- Carlos IV, King of Spain (1748 – 1819), married Princess Maria Luisa of Parma, had fourteen children

- Princess Maria Teresa of Naples and Sicily (1749 – 1750), died in infancy

- Ferdinando I, King of the Two Sicilies (1751 – 1825), married (1) Maria Carolina of Austria, had seventeen children (2) Lucia Migliaccio, Duchess of Floridia, morganatic marriage, no children

- Infante Gabriel of Spain (1752 – 1788), married Infanta Mariana Vitória of Portugal, had three children

- Princess Maria Ana of Naples and Sicily (1754 – 1755), died in infancy

- Infante Antonio Pascual of Spain (1755 – 1817), married his niece Infanta Maria Amalia of Spain, no children

- Infante Francisco Javier of Spain (1757 – 1771), died in his teens from smallpox

Royal Palace of Caserta in Caserta, Italy; Credit – By Carlo Pelagalli, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=52612424

As Queen of Naples and Sicily, Maria Amalia had great influence and actively participated in state affairs. After the birth of her first son in 1747, she was given a seat on the council of state. Maria Amalia ended the careers of several politicians she disliked. She played an important role in the planning and construction of the Royal Palace of Caserta.

Maria Amalia’s in-laws: King Felipe V of Spain and Elisabeth Farnese of Parma, Queen of Spain in 1739

Carlos’ father Felipe V, King of Spain died of a stroke at the age of 62 on July 9, 1746, and Carlos’ only surviving elder half-brother Fernando succeeded to the Spanish throne as Fernando VI, King of Spain, and reigned for thirteen years. However, Fernando’s marriage to Barbara of Portugal produced no children, and so upon his death in 1759, his elder surviving half-brother, Maria Amalia’s husband Carlos, succeeded him as King Carlos III of Spain. With great sadness, by both Carlos and the people of Naples and Sicily, Carlos abdicated the thrones of Naples and Sicily in favor of his eight-year-old third son Ferdinando with a regency council ruling until his sixteenth birthday.

Maria Amalia, her husband, and their surviving children moved from Naples to Madrid, Spain in the autumn of 1759. Besides leaving their third son Ferdinando who was now King of Naples and Sicily, they left their eldest son Felipe who was excluded from the succession due to learning disabilities and epilepsy. Felipe lived hidden away at the Palace of Portici in the Kingdom of Naples, occasionally being visited by his brother King Ferdinando. Felipe died, aged 30, in 1777, from smallpox.

Maria Amalia had lived in her husband’s Italian kingdoms for twenty-one years and did not like Spain. She complained about the food, the language, which she refused to learn, the climate, the Spaniards, whom she regarded as passive, and the Spanish courtiers, whom she regarded as ignorant and uneducated. She planned reforms for the Spanish court but did not have time to complete them.

A posthumous portrait of Maria Amalia, circa 1761; Credit – Wikipedia

On September 27, 1760, a year after arriving in Spain, 35-year-old Maria Amalia died from tuberculosis at the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid, Spain. She was buried in the Pantheon of Kings in the Royal Crypt of the Monastery of El Escorial. Upon Maria Amalia’s death, her husband Carlos said, “In twenty-two years of marriage, this is the first serious upset that Amalia has given me.” After Maria Amalia’s death, Carlos remained unmarried. He survived his wife by twenty-eight years, dying, aged 72, on December 14, 1788, at the Royal Palace of Madrid in Spain. He was buried in the Pantheon of Kings in the Royal Crypt of the Monastery of El Escorial.

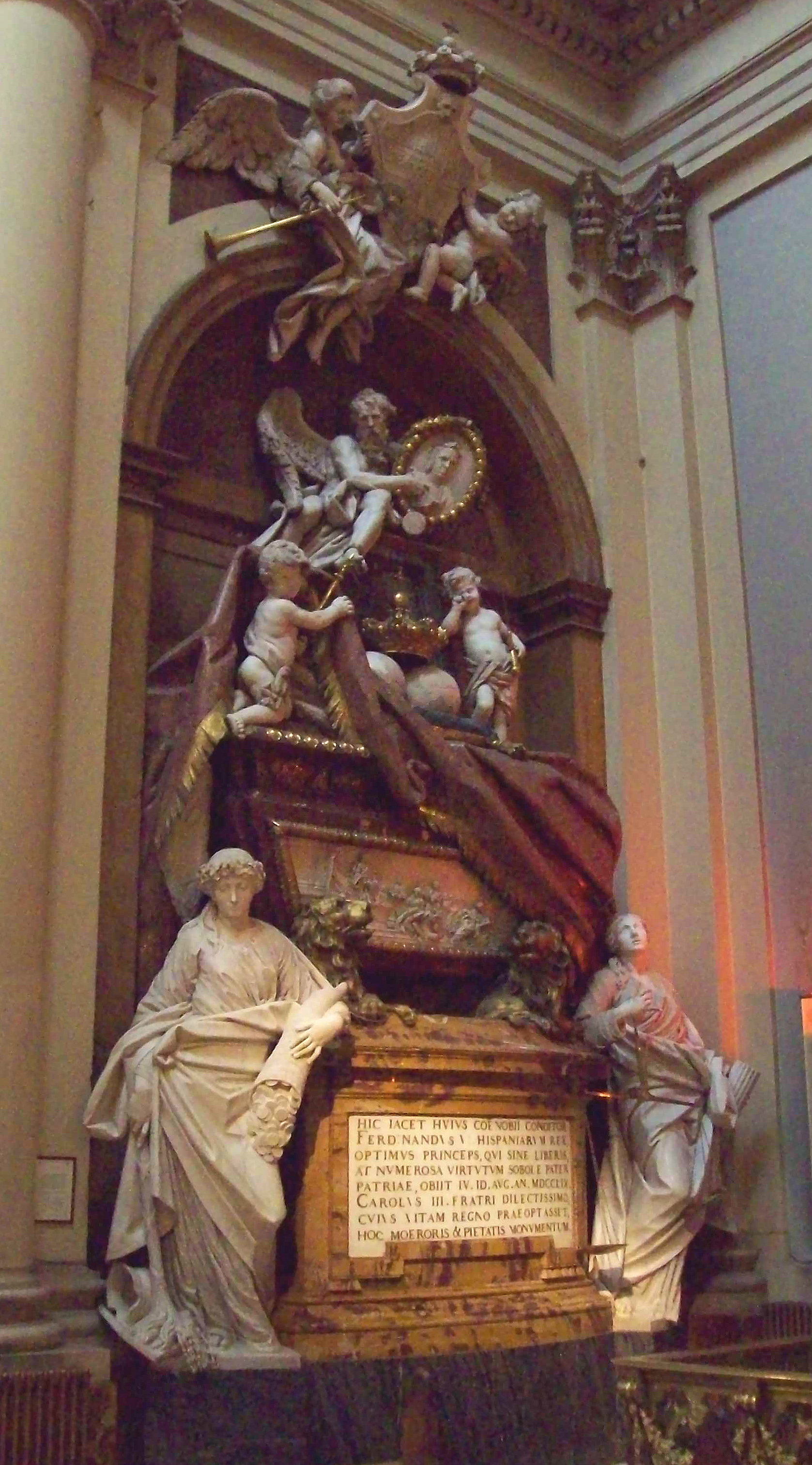

Tomb of Maria Amalia of Saxony, Queen of Spain; Credit – www.findagrave.com

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Augustus III of Poland (2022) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_III_of_Poland (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

- Flantzer, Susan. (2023) Carlos III, King of Spain, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, King of Naples, King of Sicily, Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/carlos-iii-king-of-spain-duke-of-parma-and-piacenza-king-of-naples-king-of-sicily/ (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

- María Amalia de Sajonia (2022) Wikipedia (Spanish). Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mar%C3%ADa_Amalia_de_Sajonia (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

- Maria Amalia di Sassonia (2022) Wikipedia (Italian). Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Amalia_di_Sassonia (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

- Maria Amalia of Saxony (2022) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Amalia_of_Saxony (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

- Maria Amalia von Sachsen (1724–1760) (2023) Wikipedia (German). Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Amalia_von_Sachsen_(1724%E2%80%931760) (Accessed: January 2, 2023).