by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy; Credit – Wikipedia

Margaret of York was the third wife of Charles I the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Born on May 3, 1446, at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire, England, Margaret was the sixth of the twelve children and the third of the four daughters of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, both great-grandchildren of King Edward III of England, and the sister of two Kings of England, Edward IV and Richard III. Margaret’s paternal grandparents were Richard of Conisbrough, 3rd Earl of Cambridge and his first wife Anne Mortimer. Her maternal grandparents were Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland and his second wife Joan Beaufort.

Margaret had eleven siblings:

- Anne of York (1439 – 1476), married (1) Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter, had one daughter (2) Sir Thomas St. Leger, Anne died giving birth to a daughter

- Henry of York (born and died 1441), died in infancy

- Edward IV, King of England (1442 – 1483), married Elizabeth Woodville, had ten children including the ill-fated Edward V, King of England and Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII, King of England

- Edmund, Earl of Rutland (1443 – 1460), unmarried, killed at the Battle of Wakefield during the Wars of the Roses

- Elizabeth of York (1444 – circa 1503), wife of John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, had eleven children

- William of York (born and died 1447), died in infancy

- John of York (born and died 1448), died in infancy

- George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence (1449 – 1478), married Isabel Neville, had four children, George was executed by his brother King Edward IV

- Thomas of York (born and died circa 1450/1451), died in infancy

- Richard III, King of England (1452 – 1485), married Anne Neville, had one son Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales who predeceased his father, Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field

- Ursula of York (born and died 1455), died in infancy

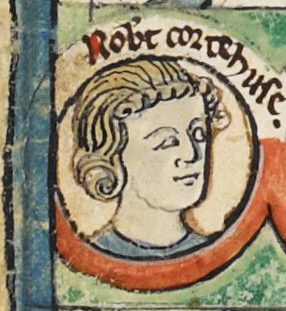

Margaret’s father Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, detail from the frontispiece of the illuminated manuscript Talbot Shrewsbury Book; Credit – Wikipedia

Margaret’s father Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York was the leader of the House of York during the Wars of the Roses until he died in battle in 1460. In 1399, Henry of Bolingbroke, the eldest son of John of Gaunt, the third surviving son of King Edward III, deposed his first cousin King Richard II and assumed the throne as King Henry IV. Henry IV’s reigning house was the House of Lancaster as his father was Duke of Lancaster and Henry had assumed the title upon his father’s death. Henry IV’s eldest son King Henry V retained the throne but died when his only child King Henry VI was just nine months old. Henry VI’s right to the crown was challenged by Margaret’s father Richard, 3rd Duke of York, who could claim descent from Edward III’s second and fourth surviving sons, Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence and Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York.

During the early reign of King Henry VI, Margaret’s father held several important offices and quarreled with the Lancastrians at court. In 1448, he assumed the surname Plantagenet and then assumed the leadership of the Yorkist faction in 1450. The first battle in the long dynastic struggle called the Wars of the Roses was the First Battle of St. Albans in 1455. As soon as Margaret’s brothers Edward, the future King Edward IV, known then as the Earl of March, and Edmund, Earl of Rutland were old enough, they joined their father, fighting for the Yorkist cause. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York was killed on December 30, 1460, at the Battle of Wakefield along with his son Edmund who was only 17 years old.

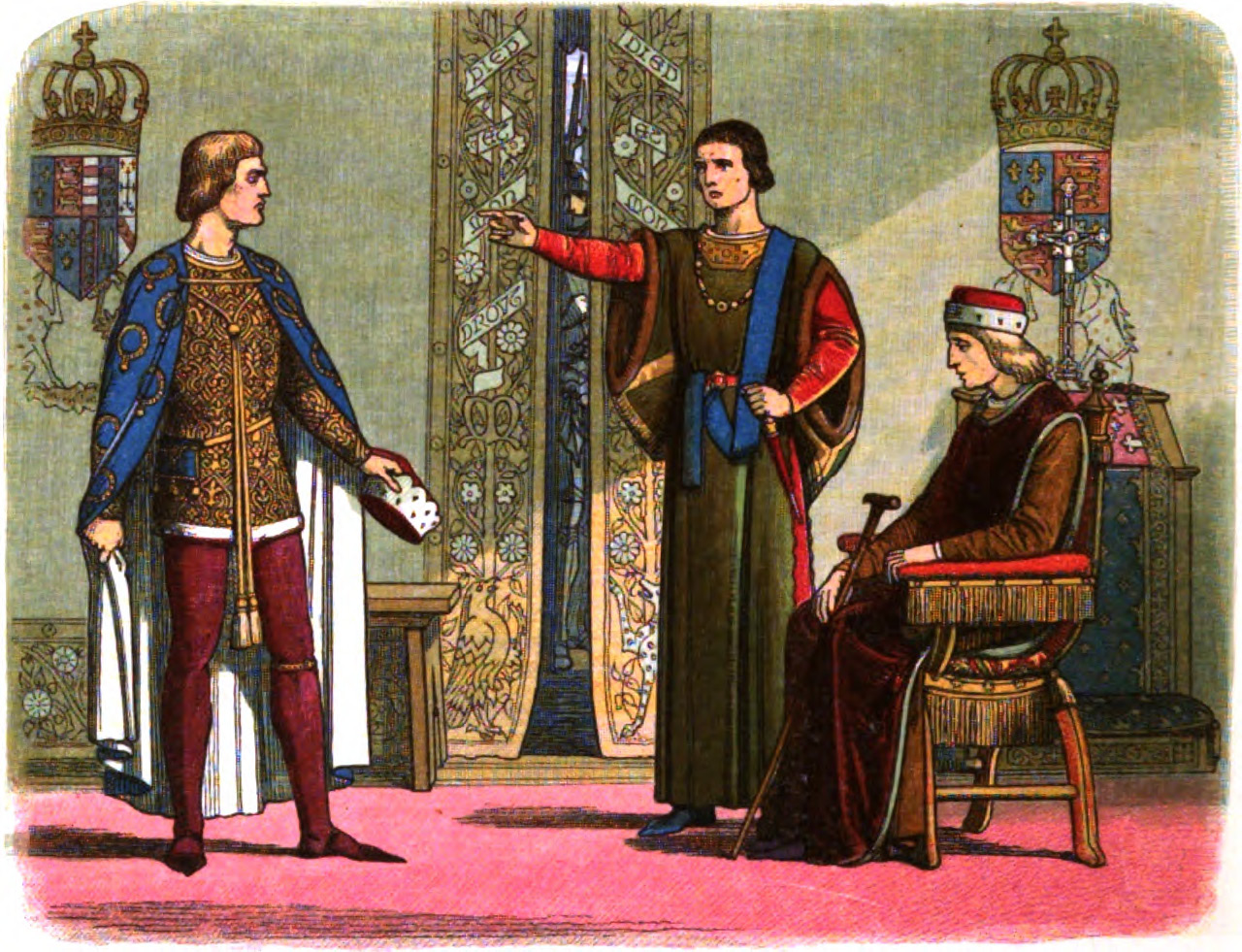

Margaret’s brother King Edward IV of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Margaret’s brother Edward, Earl of March (the future King Edward IV) was now the leader of the Yorkist faction. On February 3, 1461, Edward defeated the Lancastrian army at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross. Edward then took a bold step and declared himself King of England on March 4, 1461. His decisive victory over the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton on March 29, 1461, cemented his status as King of England. He was crowned at Westminster Abbey on June 28, 1461. However, the former king, Henry VI, still lived and fled to Scotland.

Margaret’s husband Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy; Credit – Wikipedia

In February 1468, arrangements were made for Margaret to marry Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy after the death of his second wife Isabella of Bourbon. Margaret and Charles were half-second cousins. They were both great-grandchildren of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the third surviving son of King Edward III but from different wives of John. The Burgundian State consisted of parts of the present-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, and Germany. On June 23, 1468, Margaret left England to sail across the English Channel to the County of Flanders, part of the Burgundian State, now part of Belgium

Margaret arrived in Flanders on June 25, 1468. The following day, Margaret met Charles’s mother Isabella of Portugal and Charles’s only child 11-year-old Mary of Burgundy, the daughter of his second wife Isabella of Bourbon. Their meeting was a resounding success, and the three of them would remain close for the rest of their lives. On June 27, 1468, Margaret met Charles for the first time. They were married privately on July 3, 1468, at the home of a wealthy merchant in Damme, Flanders.

Margaret’s stepdaughter Mary, Duchess of Burgundy; Credit – Wikipedia

Margaret and Charles had no children but Margaret was the stepmother to Charles’s daughter Mary, Duchess of Burgundy:

- Mary, Duchess of Burgundy (1457 – 1482), married Maximilian, Archduke of Austria, later Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, had three children

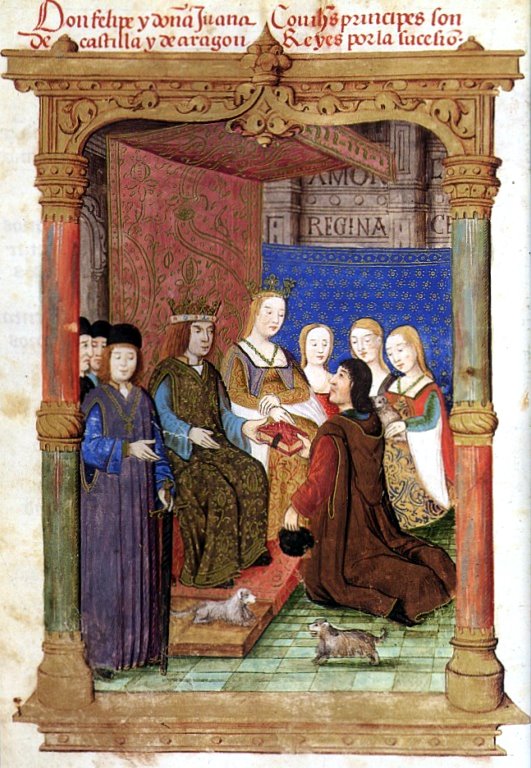

Mary married Maximilian, Archduke of Austria in 1477. After Mary’s death, he became Holy Roman Emperor. Mary and Maximilian had three children including Philip of Habsburg who inherited his mother’s domains following her death but predeceased his father. Philip married Juana I, Queen of Castile and León, becoming King-Consort of Castile upon her accession in 1504, and they were the parents of the Holy Roman Emperors Charles V and Ferdinand I, and the grandparents of Felipe II, King of Spain.

Meanwhile, in England, Henry VI returned from Scotland in 1464 and participated in an ineffective uprising. In 1465, Henry VI was captured and taken to the Tower of London. King Edward IV had a falling out with his major supporters, his brother George, Duke of Clarence and his first cousin Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as the Kingmaker. Henry VI’s wife Margaret of Anjou, Clarence, and Warwick formed an alliance at the urging of King Louis XI of France. Edward IV was forced into exile, and Henry VI was restored to the throne on October 30, 1470. Edward and his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III) fled to Burgundy where they knew they would be welcomed by their sister Margaret and her husband Charles the Bold. Charles provided funds and troops to Edward to enable him to launch an invasion of England in 1471. Edward returned to England in early 1471 and defeated the Lancastrians at the Battle of Barnet. The final decisive Yorkist victory was at the Battle of Tewkesbury on May 4, 1471, where Henry VI’s child Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales was killed. Henry VI was returned to the Tower of London and died on May 21, 1471, probably murdered on orders from Edward IV. Edward IV remained King of England until he died in 1483, a few weeks before his 41st birthday.

The Burgundian State during the reign of Charles the Bold; Credit – By Marco Zanoli, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3977827

Charles the Bold’s main objective was to become a king by acquiring territories bordering and in between the territories of the Burgundian State. This caused the Burgundian Wars (1474 – 1477). The war ended when Charles was killed at the Battle of Nancy in 1477. He was interred at the Church of Our Lady in Bruges in Flanders, now in Belgium.

The Duchy of Burgundy and several other Burgundian lands then became part of France, and the Burgundian Netherlands and Franche-Comté were inherited by Charles’s daughter Mary, who was now the reigning Duchess of Burgundy. Mary’s lands eventually passed to the House of Habsburg upon her death because of her marriage to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. After Charles the Bold died, Margaret proved to be invaluable to Burgundy. Regarded as skillful and intelligent, Margaret provided guidance and advice to her stepdaughter Mary, using her own experiences in the court of her brother King Edward IV of England.

In 1482, five years after the death of her husband in battle, Margaret was dealt another devastating blow. Despite being pregnant, Mary participated in a hunt in the woods near Wijnendale Castle in Flanders. She was an experienced rider and held her falcon in one hand and the reins in the other hand. However, Mary’s horse stumbled over a tree stump while jumping over a newly dug canal. The saddle belt under the horse’s belly broke causing Mary to fall out of the saddle and into the canal with the horse on top of her. Mary was seriously injured and was transported to Prinsenhof, her palace in Bruges, where she died, aged twenty-five, several weeks later from internal injuries. Mary was buried next to her father in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges in Flanders, now in Belgium.

Mary’s brother King Richard III of England; Credit – Wikipedia

Margaret suffered more personal tragedies. Her brother George, Duke of Clarence was found guilty of plotting against his brother King Edward IV, imprisoned in the Tower of London, and privately executed on February 18, 1478. Edward IV died on April 9, 1483, a few weeks before his 41st birthday. His cause of death is not known for certain. King Edward IV was very briefly succeeded by his 12-year-old son as King Edward V until he and his brother Richard, Duke of York (Unofficial Royalty article coming soon) were declared illegitimate by an Act of Parliament and their uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester crowned King Richard III. Margaret’s nephews Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York were the Princes in the Tower, whose fate remains unknown. Margaret’s brother King Richard III lost his life and his crown at the Battle of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. On that day, Henry Tudor, the Lancastrian faction leader, became the first monarch of the House of Tudor, King Henry VII. Margaret’s niece Elizabeth of York, Edward IV’s daughter, married King Henry VII in 1486, and they were the parents of King Henry VIII.

Margaret was a strong supporter of anyone willing to challenge King Henry VII. She backed both Lambert Simnel, who claimed to be first Richard, Duke of York, (son of Margaret’s brother King Edward IV, one of the Princes in the Tower), and then Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick (son of Margaret’s brother George, Duke of Clarence, executed for treason in 1499) and Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be Richard, Duke of York. King Henry VII found Margaret problematic but there was little he could do since she was protected by her step-son-in-law Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor. Lambert Simnel became the figurehead of a Yorkist uprising that was crushed in 1487. He was pardoned because of his young age and was thereafter employed by the royal household. Margaret acknowledged Perkin Warbeck as her nephew and offered financial backing to support Warbeck’s attempt to take the throne, hiring mercenaries to accompany him on an expedition to England in 1495. Warbeck made several landings in England but met strong resistance and surrendered in 1497. After his capture, Warbeck was imprisoned in the Tower of London and executed in 1499.

Margaret remained an influential matriarch in the family and devoted the last years of her life to the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of her husband Charles the Bold. In 1500, she became the godmother of Charles V, the future Holy Roman Emperor, King of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Lord of the Netherlands, Duke of Burgundy, and the grandson of Mary, Duchess of Burgundy and Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Mechelen Palace where Margaret spent much of her widowhood, and died; Credit – By Ad Meskens – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12476932

Margaret survived her husband Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy by twenty-six years, dying on November 23, 1503, at the age of 57, at her main residence during her widowhood, Mechelen Palace, in Mechelen, then in the County of Flanders, part of the Burgundian State, now in Belgium. In her will, Margaret asked to be buried in the Church of the Cordeliers, the church of the Franciscan or Grey Friars in Mechelen. Part of this church survives as part of the Mechelen Cultural Centre but Margaret’s tomb was destroyed at the end of the 16th century.

Margaret is the major character in the 2008 novel A Daughter of York by Anne Easter Smith, where this writer was first introduced to her. The book begins in 1460 with fourteen-year-old Margaret mourning the death at the Battle of Wakefield of her father and brother, Richard, 3rd Duke of York and Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and continues through her marriage and the aftermath of her husband’s death.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De Win, Paul, 2005. Danse Macabre Around the Tomb and Bones of Margaret of York. [online] The Ricardian. Available at: <http://www.thericardian.online/> [Accessed 28 August 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Charles the Bold – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_the_Bold> [Accessed 28 August 2022].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2022. Margaret of York – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_of_York> [Accessed 28 August 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2022. Cecily Neville, Duchess of York. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/cecily-neville-duchess-of-york/> [Accessed 28 August 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2016. King Edward IV of England. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-edward-iv-of-england/> [Accessed 28 August 2022].

- Flantzer, Susan, 2022. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/richard-plantagenet-3rd-duke-of-york/> [Accessed 28 August 2022].

- Jones, Dan, 2012. The Plantagenets. New York: Viking.

- Weir, Alison, 1995. The Wars of the Roses. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Williamson, David, 1996. Brewer’s British Royalty. London: Cassell.