by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Erik XIV, King of Sweden; Credit – Wikipedia

Erik XIV, King of Sweden is known for the Sture Murders in which he and his guards killed six men. Deposed by his half-brother, Erik was imprisoned, and likely murdered by arsenic poisoning. He was born on December 13, 1533, at Tre Kronor Castle in Stockholm, Sweden, the only child of Gustav I Vasa, King of Sweden and his first wife Katharina of Saxe-Lauenburg. In September 1535, during a ball given in honor of her brother-in-law, Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway, who was visiting Sweden, the pregnant Katharina fell while dancing with Christian III. The fall confined her to bed and led to pregnancy complications, and she died on September 23, 1535, the day before her twenty-second birthday along with her unborn child. Erik was not yet two years old.

Gustav I Vasa, King of Sweden, Erik’s father; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1536, Erik’s father Gustav I married his second wife Margareta Leijonhufvud. Margareta was a member of the Leijonhufvud family, one of Sweden’s most powerful noble families. Her constant pregnancies took a toll on her health and she died from pneumonia at the age of 35 in 1551.

Erik had ten half-siblings from his father’s second marriage:

- Johan III, King of Sweden (1537 – 1592), married (1) Katarina Jagellonica of Poland, had three children including his successor Sigismund III Vasa, King of Sweden (2) Gunilla Bielke, had one son

- Katarina Gustavsdotter Vasa (1539 – 1610), married Edzard II, Count of East Frisia, had ten children

- Cecilia Gustavsdotter Vasa (1540 – 1627), married Christoph II, Margrave of Baden-Rodemachern, had seven children

- Magnus Gustavson Vasa, Duke of Östergötland (1542 – 1595), unmarried, mentally ill

- Karl Gustavson Vasa (born and died 1544), died in infancy

- Anna Gustavsdotter Vasa (1545 – 1610), married of Georg Johann I, Count Palatine of Veldenz, had eleven children

- Sten Gustavson Vasa (1546 – 1547), died in infancy

- Sofia Gustavsdotter Vasa (1547 – 1611), married Magnus II, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg, had six children but only one lived past infancy

- Elisabet Gustavsdotter Vasa (1549 – 1597), married Christoph, Duke of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch, had one daughter

- Karl IX, King of Sweden (1550 – 1611), married (1) Maria of Palatinate-Simmern, had six children but only one daughter survived childhood (2) Christina of Holstein-Gottorp, had four children including his successor Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden

In 1552, Erik’s father Gustav I married his third wife 17-year-old Katarina Stenbock, the daughter of Gustaf Olofsson Stenbock and Brita Eriksdotter Leijonhufvud, who was the sister of King Gustav I’s second wife Margareta Leijonhufvud. They had no children. Katarina survived her husband by sixty-one years, dying on December 13, 1621, aged 86.

Erik, along with his half-brother, the future Johan III, King of Sweden, was well-educated by tutors and excelled in foreign languages, mathematics, and history. In 1557, King Gustav I wrote his will and divided his kingdom into hereditary duchies for his sons: Erik, Duke of Kalmar; Johan, Duke of Finland; Magnus, Duke of Östergötland; and Karl, Duke of Södermanland. When Erik started to make public appearances, he was referred to as the “chosen king” (Swedish: utvald konung) until the Riksdag (parliament) granted him the title of “hereditary king” (Swedish: arvkonung) in 1560.

When Erik was in his early 20s, his relationship with his father became very strained. Against his father’s wishes, Erik entered into negotiations for a marriage with the future Queen Elizabeth I of England and pursued her for several years. The death of Gustav I Vasa, King of Sweden on September 29, 1560, prevented Erik from traveling to England to press Queen Elizabeth I for her hand in marriage. His later marriage proposals to Mary, Queen of Scots, Renata of Lorraine, Anna of Saxony, and Christine of Hesse were also rejected.

Erik XIV, King of Sweden opposed the Swedish nobility. He chose as his closest advisor Göran Persson who held the same views as Erik and who had narrowly escaped execution under the reign of Erik’s father. Erik summoned the Riksdag, the Swedish legislature, at Arboga where, under Erik’s urging, the Arboga Articles were adopted curtailing the authority of his half-brothers Johan and Karl in the dukedoms given to them by their father. As a further move against his half-brother Johan, Duke of Finland, Erik placed the city of Reval, now Tallinn, Estonia, under his protective power and led expansionist campaigns of conquest in Estonia.

Eriks’s brother Johan then turned to Sigismund II Augustus, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania for an alliance. He married Katarina Jagellonica of Poland, the sister of Sigismund II Augustus and in exchange received a substantial sum of money and land in Livonia (located in present-day Estonia and Latvia) which then hindered Erik’s expansionist policy. Erik’s response was to send 10,000 troops to besiege Johan’s home Turku Castle in Turku, Finland. On August 12, 1563, Turku Castle surrendered. Johan was tried for high treason and sentenced to death but he was pardoned and imprisoned with his wife at Gripsholm Castle in Mariefred, Södermanland, Sweden.

Karin Månsdotter, Erik XIV, and Göran Persson; Credit – Wikipedia

Sometime in 1565, Erik entered into a relationship with low-born Karin Månsdotter, a maid to his half-sister Elisabet. In 1567, Erik decided to marry Karin following the agreement he made with the state council in 1561 that he could marry whomever he pleased. The marriage plans were supported by his advisor Göran Persson. On December 29, 1567, Erik and Karin were married morganatically in a secret ceremony. A second official wedding was held in Storkyrkan (Great Church) in Stockholm, Sweden on July 4, 1568, followed the next day by Karin’s coronation as Queen of Sweden.

Erik and Karin Månsdotter had four children. The first two were born before the second official marriage in 1568 (see below) but were later legitimized. The last two died in early childhood.

- Princess Sigrid (1566 – 1633), married Henrik Klasson Tott, had three children

- Prince Gustav (1568 – 1607), unmarried

- Prince Henrik (1570 – 1574)

- Prince Arnold (1572 – 1573)

Erik had suffered from mental health issues and from 1563 onwards these issues worsened. His decisions became more illogical and he exhibited violent behavior. Erik’s suspicion of the nobility led him to be suspicious of the Sture family, then headed by Svante Stensson Sture who was married to Märta Erikdotter Leijonhufvud, the sister of Margareta Leijonhufvud, the second wife of Erik’s father. Erik lacked a legal heir and feared that the Sture family might claim his throne. These fears resulted in the Sture Murders, the murders of five incarcerated Swedish nobles and Erik’s former tutor.

Svante Stensson Sture; Credit – Wikipedia

On May 24, 1567, in Uppsala Castle, Erik and his guards killed six men. Svante Stensson Sture, and his sons Nils Svantesson Sture and Erik Svantesson Sture, Abraham Gustafsson Stenbock (brother of Katarina Gustavsdotter Stenbock, the third wife of King Gustav I Vasa), and Ivar Ivarsson Liljeörn were killed in their cells inside the castle. Erik personally stabbed Nils Svantesson Sture to death. After the murders, Erik’s former tutor Dionysius Beurreus found him outside the castle in a state of agitation. Beurreus tried to calm Erik but instead, Erik issued an order to kill Beurreus and vanished into a nearby forest. The guards then stabbed Beurreus to death. Abraham Gustafsson Stenbock and Ivar Ivarsson Liljeörn already had been sentenced to death but Svante Sture and his sons were executed without trial on Erik’s order and the unfortunate Beurreus was killed on a whim.

Johan III, King of Sweden, Erik’s eldest half-brother and successor; Credit – Wikipedia

On May 27, 1567, Erik was found in the village of Odensala, disguised as a peasant and confused, and was brought to Stockholm. Eventually, he calmed down and then asked both God and the Swedish people for forgiveness. He sought reconciliation with the relatives of the murdered. For a while, a regency council took over the government of the country, freed Erik’s half-brother Johan from prison, and sentenced Erik’s advisor Göran Persson to death. However, this death sentence was not carried out for fear of how Erik would react when he recovered. The king’s younger half-brothers led a revolt against Erik which ended in his removal as King of Sweden in September 1568 and his eldest half-brother succeeding to the throne as Johan III, King of Sweden. In January 1569, the Riksdag legally dethroned Erik.

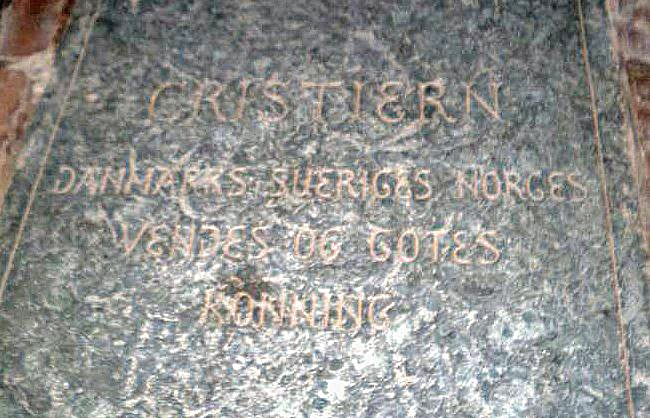

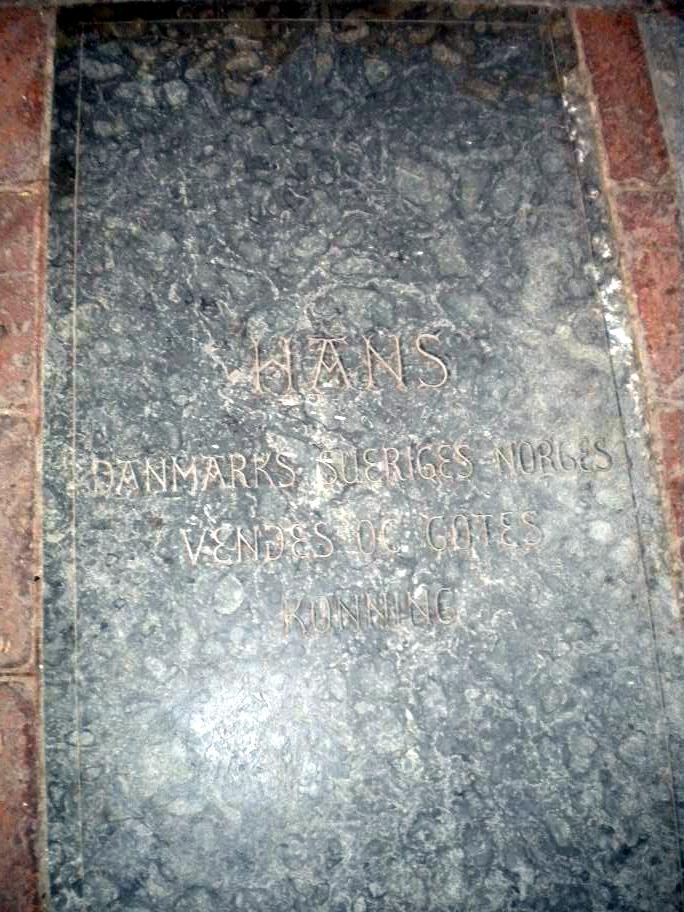

Erik was imprisoned in various castles for nine years. He died on February 26, 1577, aged 43, at Örbyhus Castle in Örbyhus, Sweden. He was most likely murdered due to the three major conspiracies that attempted to depose his half-brother Johan III and place Erik back on the Swedish throne. An examination of his remains in 1958 confirmed that Erik probably died of arsenic poisoning. Erik XIV, King of Sweden was originally buried in a crypt at Västerås Cathedral in Västerås, Västmanland, Sweden. In 1797, Erik’s remains were reburied at Västerås Cathedral in a Carrara marble sarcophagus that King Gustav III of Sweden originally ordered for himself.

Tomb of Erik XIV, King of Sweden; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Kingdom of Sweden Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Kingdom of Sweden Index

- Swedish Orders and Honours

- Swedish Royal Dates

- Swedish Royal Burial Sites

- Swedish Royal Christenings

- Swedish Royal FAQs

- Swedish Royal Residences

- Swedish Royal Weddings

- Line of Succession to the Throne of Sweden

- Profiles of the Swedish Royal Family

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2021. Erik XIV. – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erik_XIV.> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Eric XIV of Sweden – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_XIV_of_Sweden> [Accessed 30 April 2021].

- Sv.wikipedia.org. 2021. Erik XIV – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erik_XIV> [Accessed 30 April 2021].