by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

On September 10, 1898, while walking to a ferry landing on Lake Geneva in Geneva, Switzerland with her lady-in-waiting, sixty-year-old Empress Elisabeth of Austria was stabbed in the heart by twenty-five-year-old Luigi Lucheni.

Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria

Empress Elisabeth of Austria, 1897; Credit – Wikipedia

Elisabeth, Duchess in Bavaria, known as Sisi, was born on December 24, 1837, at Herzog-Max-Palais (Duke Max Palace) in Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, now in Bavaria, Germany. She was the fourth of the nine children of Maximilian Joseph, Duke in Bavaria, from a junior branch of the House of Wittelsbach, and Princess Ludovika of Bavaria, the daughter of Maximilian I Joseph, King of Bavaria and his second wife Caroline of Baden.

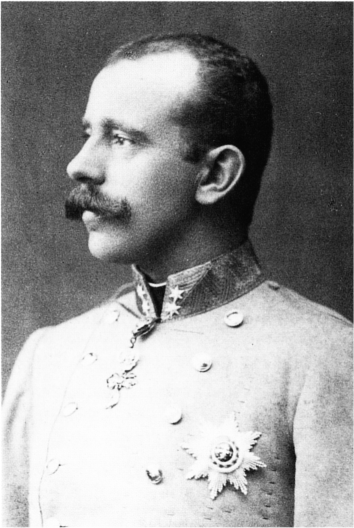

In 1853, Helene, the eldest daughter in the family, traveled to the resort of Bad Ischl, Upper Austria with her mother and younger sister Elisabeth to meet her first cousin Franz Joseph, Emperor of Austria with the hopes that Helene would become his bride. Instead, Franz Joseph fell in love with the 15-year-old Elisabeth. Franz Joseph told his mother that if he could not marry Elisabeth, he would not marry at all. Five days later their engagement was officially announced. Franz Joseph and Elisabeth were married on April 24, 1854, at the Augustinerkirche, the parish church of the Imperial Court of the Habsburgs, a short walk from Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria.

Elisabeth and Franz Joseph had three daughters and a son. Their eldest daughter died in childhood. The heir to the throne was their son Crown Prince Rudolf. The marriage was not a happy one for Elisabeth. Although her husband loved her, Elisabeth had difficulties adjusting to the strict Austrian court and did not get along with Imperial Family members, especially Sophie Friederike of Bavaria, Archduchess of Austria, her controlling mother-in-law who was also her maternal aunt. Elisabeth felt emotionally distant from her husband and fled from him, as well as her duties at court, by frequent traveling.

Crown Prince Rudolf married Princess Stephanie of Belgium, daughter of King Leopold II of the Belgians. The couple had one child, a daughter. On January 30, 1889, at Mayerling, a hunting lodge in the Vienna Woods which Rudolf had purchased, Rudolf shot his 17-year-old mistress Baroness Mary Vetsera and then shot himself in an apparent suicide plot.

The Assassin – Luigi Lucheni

Lucheni’s police file; Credit – Wikipedia

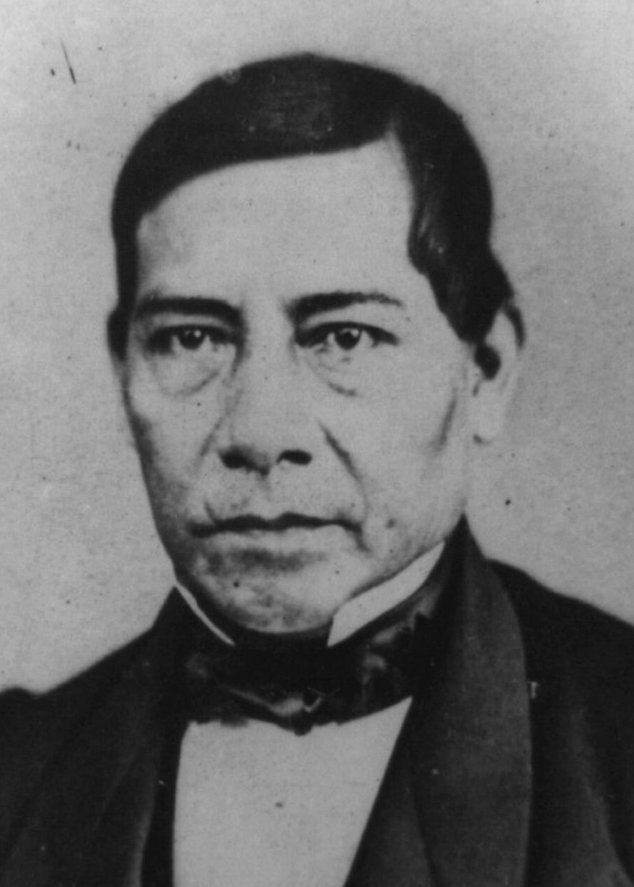

Twenty-five-year-old Luigi Lucheni was born in Paris, France on April 22, 1873. His father is unknown and his mother was an Italian worker named Luigia Laccheni who left her son at a foundling hospital. Lucheni moved to Italy in 1874 and spent his childhood in orphanages and with foster families. He left foster care when he was sixteen years old and worked odd jobs in Italy, Switzerland, and Austria-Hungary. Lucheni served in the Italian Army from 1894 – 1897.

In 1898, Lucheni returned to Switzerland where he did some construction work. The poverty of the lower classes and of his own life made Lucheni hate authority. He began to turn to the philosophy of anarchy – a society without authorities or a governing body. Soon he began to call himself an anarchist although he was not in contact with any other anarchists. Lucheni came to the conclusion that emperors, empresses, kings, queens, princes, and princesses were annoying parasites.

In May 1898, when King Umberto I of Italy brutally suppressed a workers’ uprising in Milan, Lucheni vowed revenge. He made plans to assassinate Umberto I but had no money for a trip to Italy. King Umberto I was assassinated in 1900 by anarchist Gaetano Bresci, an act of revenge for what happened in Milan.

Lucheni then focused his attention on assassinating a royal person traveling in Switzerland. He originally wanted to assassinate Prince Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the Orléanist claimant to the throne of France, but he had left Geneva earlier than expected. Lucheni then selected Elisabeth as his victim when a Geneva newspaper revealed that the woman traveling under the pseudonym of “Countess of Hohenembs” was Empress Elisabeth of Austria. Because he did not have enough money to purchase a proper weapon, Lucheni chose a simple file to which he added a wooden handle as the murder weapon.

The file that was used to stab Elisabeth on display at the Hofburg Palace; Credit – http://www.hofburg-wien.at

The Assassination

Last photograph of Elisabeth and her lady-in-waiting the day before her death; Credit – Wikipedia

After Crown Prince Rudolf’s suicide, Elisabeth spent little time with her husband, preferring to travel. In September 1898, despite being warned about possible assassination attempts, Elisabeth traveled incognito to Geneva, Switzerland where she stayed at the Hotel Beau-Rivage.

An artist’s rendition of the stabbing of Elisabeth by Luigi Lucheni; Credit – Wikipedia

On September 10, 1898, Elisabeth was due to take a ferry across Lake Geneva to the town of Territet. As Elisabeth and Countess Irma Sztáray, her lady-in-waiting, were walking to the ferry’s landing, Luigi Lucheni rushed at her and stabbed her in the heart with a pointed file. The puncture wound was so small that it was initially not noticed and it was thought that Elisabeth had just been punched in the chest. Elisabeth thanked all the people who had rushed to help and conversed with Countess Irma Sztáray about the incident.

Embed from Getty Images

Elisabeth being carried on an improvised stretcher

Only when onboard the ferry did she finally collapse and then the severity of Elisabeth’s injury was realized. The ferry captain ordered the ferry back to Geneva and the empress was taken back to the hotel on an improvised stretcher. A doctor and a priest were summoned. The doctor confirmed that there was no hope and a priest administered the Last Rites. Empress Elisabeth of Austria died without regaining consciousness.

The Funeral

The funeral procession Of Empress Elisabeth in Vienna, (September 17, 1898); Credit – Wikipedia

Elisabeth’s body was placed in a triple coffin: two inner ones of lead and the third exterior one in bronze. The coffins were fitted with two glass panels, covered with doors, which could be slid back to allow her face to be seen. On September 13, 1898, Emperor Franz Joseph’s official representatives arrived in Geneva to identify the body. The coffins were then sealed. The next day, Elisabeth’s final journey back to Vienna began aboard a funeral train. Upon arriving in Vienna, Elisabeth’s coffin was brought to the Hofburg Palace chapel to lie in state.

Embed from Getty Images

Empress Elisabeth’s coffin lying in state at Hofburg Palace chapel

Elisabeth had wanted to be buried in Corfu, Greece where she had built a home for herself near the sea. However, arrangements were made to bury her in the Imperial Crypt at the Capuchin Church in Vienna, the traditional burial site for the Habsburgs, which is in the care of the monks from the cloister. The burial place of the Habsburgs is so unlike the soaring cathedral containing the other royal burial sites that this author has visited. The Capuchin Church is small and is on a street with traffic, shops, stores, restaurants, and cafes. Walking past the church, one would never think the burial place of emperors is there.

Capuchin Church in Vienna (Cloister on left, Church in middle, Imperial Crypt on right); Credit – Susan Flantzer

On September 17, 1898, a procession formed at the Hofburg Palace to take Elisabeth the short distance to her final resting place at the Capuchin Church. Eighty-two sovereigns and other royalty along with high-ranking nobles, other dignitaries, court servants, pages, and footmen followed the funeral cortege to Capuchin Church where Cardinal Anton Josef Gruscha, Archbishop of Vienna conducted a short service. The coffin was then taken down the stairs to the Imperial Crypt (Kaisergruft in German) and the graveside committal service was held.

Embed from Getty Images

Empress Elisabeth’s coffin being carried into the Capuchin Church

By 1908, the seven vaults of the Imperial Crypt already held 129 coffins. In commemoration of Franz Joseph’s sixty years on the throne and to provide much-needed room for future interments, the Franz Joseph Vault was built along with the Crypt Chapel which now holds the most recent burials. Elisabeth’s coffin, along with that of her son Rudolf, were moved to the new Franz Joseph Vault. When Franz Joseph died in 1916, his coffin was placed in the middle with Elisabeth’s on the left and Rudolf’s on the right.

Elisabeth’s tomb on the left, Franz Joseph’s tomb in the middle, Rudolf’s tomb on the right; Credit – Susan Flantzer

What happened to the assassin, Luigi Lucheni?

Luigi Lucheni, smiling and proud after his first interrogation regarding the assassination of Empress Elisabeth, is returned to jail; Credit – Wikipedia

After stabbing Elisabeth, Lucheni ran along the Rue des Alpes heading toward the Square des Alpes. However, he was grabbed by two cab drivers who had witnessed the stabbing. They escorted Lucheni to a police officer who escorted him to a police station. Lucheni did not resist arrest. In fact, he seemed to be joyful about as he sang, “I did it! She must be dead!” When Lucheni went before a magistrate, he confessed to the murder saying, “I am an anarchist by conviction…I came to Geneva to kill a sovereign, with the object of giving an example to those who suffer and those who do nothing to improve their social position; it did not matter to me who the sovereign was whom I should kill…It was not a woman I struck, but an Empress; it was a crown that I had in view.”

Lucheni’s trial began in October 1898 and he was furious that the Canton of Geneva did not have the death penalty. He demanded his extradition to Italy, where the death penalty had not been abolished. Lucheni wanted to be executed so he could be a martyr for the anarchist movement. On November 10, 1898, Lucheni was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Lucheni acted aggressively while imprisoned, and several times he was in solitary confinement. Most of the time, he was in a large cell, with a comfortable bed, a writing desk, and a bookcase filled with books. On October 17, 1910, he became very violent, smashed everything in his cell, and was put in a straitjacket. When Lucheni became calmer, the straitjacket was removed. During the afternoon of October 19, 1910, the guards heard him singing for several hours. As night fell, the singing stopped. The guards became alarmed with the sudden silence. When they checked Lucheni’s cell, they found him hanging from the window bars by his belt which he had twisted around his neck. Efforts to revive him failed.

After Lucheni’s suicide, his head was severed from his body. His brain was removed and examined with no abnormalities detected. The head was then stored in a jar of formaldehyde at the Institute of Forensic Science of the University of Geneva. In 1985, the head was given to the Federal Museum of Pathology and Anatomy in Vienna, Austria. Lucheni’s head was buried at the Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) in Vienna in 2000.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. (2019). Elisabeth von Österreich-Ungarn. [online] Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth_von_%C3%96sterreich-Ungarn [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- De.wikipedia.org. (2019). Luigi Lucheni. [online] Available at: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Lucheni [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Empress Elisabeth of Austria. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empress_Elisabeth_of_Austria [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Luigi Lucheni. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Lucheni [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- Flantzer, Susan. (2012). A Visit to the Kaisergruft (Imperial Crypt) in Vienna. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/royal-burial-sites/austrian-imperial-burial-sites/a-visit-to-the-kaisergruft-imperial-crypt-in-vienna/ [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- Flantzer, Susan. (2016). Elisabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/elisabeth-of-bavaria-empress-of-austria/ [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- Timesmachine.nytimes.com. (1910). EMPRESS’S ASSASSIN A SUICIDE IN JAIL; Luccheni, Who Killed Elizabeth of Austria in 1898, Hangs Himself in His Cell.. [online] Available at: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1910/10/20/102049489.html [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- Timesmachine.nytimes.com. (1898). EMPRESS OF AUSTRIA SLAIN; Stabbed on a Geneva Quay by an Italian Anarchist. THE MURDERER ARRESTED Says He Went There to Kill the Duc D’Orleans. PART OF AN ANARCHIST PLOT? Reported Movement to Assassinate Principal European Sovereigns. Emperor Francis Joseph Apprised of the Tragedy While on His Way to the Army Manoeuvres in Hungary.. [online] Available at: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1898/09/11/102076759.html?pageNumber=1 [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].

- Timesmachine.nytimes.com. (1898). THE EMPRESS LAID AT REST; Vienna Crowded with Dignitaries and Visitors Generally Who Witnessed the Ceremonies. CITY DRAPED WITH BLACK Sad and Impression Scenes in the Church Attended the Benediction — Twenty-three Persons Fainted During the Procession.. [online] Available at: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1898/09/18/102077419.html?pageNumber=7 [Accessed 9 Dec. 2019].