by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

Never destined at birth to be a monarch or even married to a monarch, Princess Sophie Auguste Friederike of Anhalt-Zerbst achieved both. She was born on May 2, 1729 (New Style), in Stettin, Pomerania, Kingdom of Prussia (now Szczecin, Poland) where her father, a general in the Prussian Army, served as Governor of the city of Stettin. Sophie’s father was Prince Christian August, who reigned the Principality of Anhalt-Dornburg (now in Germany) jointly with his four brothers from 1704 – 1742. In 1742, Christian August and his surviving brother Johann Ludwig inherited the Principality of Anhalt-Zerbst upon the death of a childless cousin. Today, the territories of both principalities are located in the German federal state of Saxony-Anhalt.

Sophie’s father, Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst; Credit – Wikipedia

Sophie’s mother was Princess Johanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp, a daughter of Christian August of Holstein-Gottorp, Prince of Eutin. Even before Sophie’s birth, there already was a connection between the House of Holstein-Gottorp and the House of Romanov. Prior to his death in 1725, Peter I (the Great), Emperor of All Russia had arranged the betrothal of his daughters, his only surviving children, Anna Petrovna and Elizabeth Petrovna to two cousins from the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp. Anna Petrovna married Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp in 1725. Three years later, Anna Petrovna died as a result of childbirth complications shortly after the birth of her only child Carl Peter Ulrich, the future Peter III, Emperor of All Russia, who would marry his second cousin Sophie Auguste Friederike of Anhalt-Zerbst. Elizabeth Petrovna, the future Elizabeth I, Empress of All Russia, was due to marry Karl August of Holstein-Gottorp, the brother of Sophie’s mother Johanna Elisabeth, but he died before the wedding could be held.

Johanna of Holstein-Gottorp, Princess of Anhalt-Zerbst; Credit – Wikipedia

Sophie was the eldest of her parents’ five children and had four younger siblings but only one survived childhood:

Sophie’s governess Elizabeth Cardel, a French Huguenot known as Babet, oversaw her education. Babet instilled in Sophie a lifelong love of the French language and gave her encouragement and affection. Sophie’s fervent Lutheran father chose a strict Lutheran army chaplain, Pastor Wagner, to serve as his daughter’s teacher in religion, geography, and history. When Sophie was eight-years-old, her mother began taking her along on her travels to let the other minor German royalty know there was another princess available for marriage.

In 1739, Johanna’s brother Adolf Friedrich (the future King Adolf Frederik of Sweden) was appointed the guardian to the new Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, eleven-year-old Carl Peter Ulrich, Sophie’s future husband. As the mother of an eligible daughter and with her brother as guardian of a potential groom, Johanna took Sophie on a visit to see the new Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. Even at ten-years-old, Sophie knew that her mother and her aunts were whispering about a potential marriage between the two second cousins. In 1742, 14-year old Carl Peter Ulrich’s life dramatically changed when his unmarried maternal aunt Elizabeth I, Empress of All Russia, the surviving daughter of Peter I (the Great) Emperor of All Russia and the younger sister of Carl Peter Ulrich’s deceased mother Anna Petrovna, declared him her heir and brought him to St. Petersburg, Russia. Later that year, Carl Peter Ulrich Peter converted from Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy, was given the name Peter Feodorovich, the title Grand Duke and officially named the heir to the Russian throne.

A young Catherine shortly after arriving in Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

It was important to Empress Elizabeth that Grand Duke Peter Feodorovich, the grandson of Peter the Great, marry so that the Romanov dynasty could be continued. Whether it was a coincidence or a remembrance that she would have married Sophie’s uncle if he had not died, Empress Elizabeth picked Sophie to marry her nephew. On New Year’s Day of 1744, Sophie received an invitation to come to Moscow. Sophie was accompanied by her mother and the two immediately their journey began from Zerbst to Russia via Berlin, where they visited Friedrich II (the Great) King of Prussia, to Riga, Tallinn, Saint Petersburg, and finally to Moscow, where they arrived in February 1744.

Sophie wanted to become fully acquainted with Russia which she considered her new homeland and so she immediately began to study the Russian language, history and customs, and the Russian Orthodox religion. Among her teachers were Archbishop Simeon Feodorovich Theodorsky, a famous theologian, translator, and teacher, who instructed her in the Russian Orthodox religion, and Vasily Evdokimovich Adadurov, the author of the first Russian grammar book, who instructed her in the Russian language.

Sophie’s interest and studies in all things Russian greatly pleased Empress Elizabeth. She often studied at night, sitting at an open window in the frosty air. Soon she fell ill with a serious upper respiratory illness and her condition became so serious that her mother suggested bringing a Lutheran pastor. Sophie, however, refused the Lutheran pastor and instead sent for her religious instructor Archbishop Simeon Feodorovich Theodorsky. This incident greatly added to her popularity at the Russian court. On June 28, 1744, Sophie formally converted to Russian Orthodoxy and received the name Ekaterina (Catherine) Alexeievna, the same name and patronymic as Empress Elizabeth’s mother Catherine I, Empress of All Russia. The next day Catherine was formally betrothed to Peter.

Peter and Catherine; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine and Peter were married on August 21, 1745, at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan in St. Petersburg. A magnificent wedding banquet and ball were held at the Winter Palace. Later in the evening, Catherine and Peter were taken to their bedchamber and put to bed. The marriage was not consummated that night and many historians doubt that the marriage was ever consummated.

Peter and Catherine’s marriage was not happy but Catherine did have one son, the future Emperor Paul, and one daughter Anna Petrovna, who died in early childhood. Both children were taken by Empress Elizabeth to her apartments immediately after their births to be raised by her. Peter took Elizabeth Romanovna Vorontsova as his mistress and Catherine had affairs. Later Catherine claimed that her son and successor Paul was not the son of Peter and that they had never consummated their marriage. It is quite possible that Paul’s father was Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov, and, if this is true, then all subsequent Romanovs were not genetically Romanovs.

Children born during the marriage of Peter and Catherine:

- Paul I, Emperor of All Russia (1754 – 1801), married (1) Wilhelmina Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt (Natalia Alexeievna), died in childbirth, no issue (2) Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg (Maria Feodorovna), had issue including Emperor Alexander I, Emperor Nicholas I, Anna Pavlovna, Queen of the Netherlands

- Anna Petrovna (1757 – 1759), died in early childhood, probably the daughter of Stanisław August Poniatowski

- Alexei Grigorievich Bobrinsky (1762 – 1813), son of Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov, Catherine’s lover who helped overthrow her husband Peter III

The future Paul I, Emperor of All Russia as a child; Credit – Wikipedia

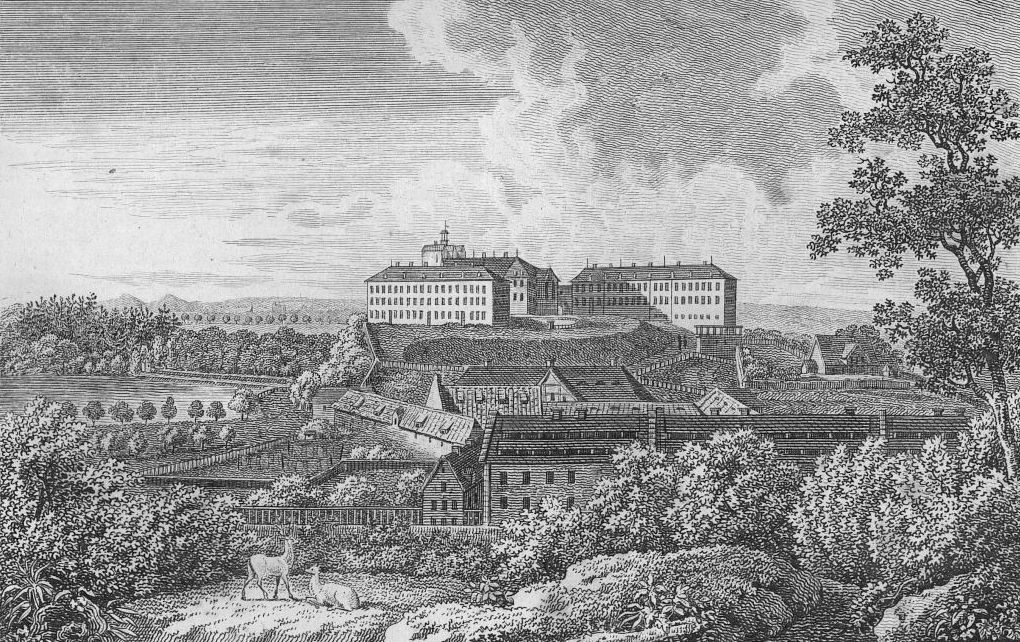

After their wedding, Peter and Catherine were granted the possession of two palaces, Oranienbaum near St. Petersburg and Lyubertsy near Moscow. While Catherine reveled in all things Russian, Peter did not. Peter’s tutors had considered him capable but lazy and never had much success with him. Peter never attempted to gain more knowledge about Russia, its people, and its history. He neglected Russian customs, behaved inappropriately during church services, and did not observe fasts and other rites. He spoke Russian poorly and infrequently. Empress Elizabeth did not allow Peter to participate in government affairs. Peter openly criticized the activities of the government, and during the Seven Years’ War publicly expressed sympathy for Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia.

Catherine and Peter’s palace at Oranienbaum; Photo Credit – Автор: IzoeKriv – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43632478

Meanwhile, Catherine became friends with Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova-Dashkova, the sister of Peter’s mistress, who introduced Catherine to several powerful political groups that opposed her husband Peter. Peter’s temperament became quite unbearable for those who resided in the palace. Catherine spent much time in her private boudoir to hide away from Peter’s abrasive personality.

Empress Elizabeth was often ill and was reluctant to show herself in public because of her ill health. In 1757, she suffered a stroke at a well-attended church service, and then her health situation became well-known. A difficult problem for her was the succession. She was childless and the Romanov dynasty had been extinct in the male line since the death of Peter II in 1730. Elizabeth did not love her nephew Peter and his political views did not suit her because he was an admirer of her enemy Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia. The sicker Elizabeth became, the more the courtiers turned away from her and tried to please the heir to the throne.

Empress Elizabeth; Credit – Wikipedia

On January 3, 1762, Elizabeth had a massive stroke and the doctors agreed she would not recover. Peter, Catherine, and others close to her gathered around her bed in the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. Elizabeth, alert and clear-headed, showed no signs of wishing to change the succession. She asked Peter to look after little Paul, whom she dearly loved. Peter quickly promised to do so, knowing that Elizabeth could change the succession with a single word. On January 5, 1762, Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia died at the age of 52 and her nephew became Peter III, Emperor of All Russia and Catherine became the Empress Consort.

Catherine in mourning clothes at the coffin of Elizabeth, Empress of All Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

As the death of Empress Elizabeth was announced to the court, the room was filled with moans and weeping. Peter was unpopular and few were looking forward to his reign. Later that day, when high government officials and military officers gathered to take the oath of allegiance to the new emperor, Peter insisted they wear bright, colorful clothing. After the oath, Peter gave a gala banquet for over a hundred guests. During the religious ceremonies for the lying-in-state of the deceased empress, Peter, according to Princess Dashkova “made faces, acted the buffoon, and imitated poor old ladies.” Peter did little to win the support of Empress Elizabeth’s friends and courtiers.

Peter’s foreign policy also did little to win supporters. At the time of Elizabeth’s death, Russia was on the verge of defeating Prussia in the Seven Years’ War. Instead, because Friedrich II (the Great), King of Prussia was his idol, Peter withdrew Russian troops from Berlin and marched against the Austrians, Russia’s ally. As Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, Peter planned war against Denmark to restore parts of Schleswig to his Duchy. This war would not benefit Russia and even the Prussian king advised Peter against taking this action. The Danish war was planned for June but never happened.

The last straw for Peter may have been the way he treated the Russian army. Peter abolished “the guard within the guard”, a group within the Preobrazhensky Regiment, created by Empress Elizabeth as her personal guard in remembrance of their support in the coup which brought her to the throne. He replaced “the guard within the guard” with his own Holstein guard and often spoke about their superiority over the Russian army.

Meanwhile, Catherine’s position deteriorated along with the position of three groups – the clergy, senior statesmen, and the Imperial Guard, the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Peter began to think about divorcing Catherine and marrying his mistress. Wisely, Catherine quietly aligned herself with the three groups. She remained calm and dignified even when Peter grossly insulted her in public. The devotion of the Preobrazhensky Regiment to Catherine was never in doubt because her lover Grigory Orlov and his four brothers were all members of the Guard.

Alexei and Grigory Orlov in the 1770s; Credit – Wikipedia

A conspiracy to overthrow Peter was planned and centered around the five Orlov brothers. On July 9, 1762 (June 29 in Old Style, the feast day of St. Peter and Paul), at Peterhof Palace, a celebration on Peter’s name day was planned. It was no coincidence that the conspirators chose this time for their attack. The day before, Peter was to travel from Oranienbaum to Peterhof. The brothers Alexei Orlov and Grigory Orlov made preparations during the weeks before the planned celebration. With threats and bribes of vodka and money, the brothers set up the guards against Peter.

Peter was late leaving Oranienbaum due to a hangover and his daily habit of reviewing his Holstein troops. He was to meet Catherine at Peterhof but when he arrived, she was not there. Eventually, Peter and the few advisers he had with him began to suspect what was happening. Peter sent members of his entourage to St. Petersburg to find out what was happening but none returned. He learned that Catherine had proclaimed herself Empress and that senior government officials, the clergy, and all the Guards supported her. Peter ordered his Holstein guards to take up defensive positions at Peterhof. They did so but were afraid to tell Peter they had no cannonballs to fire. Peter thought about fleeing but was told there were no horses available because his entourage had all arrived in carriages. Learning that Catherine and the Guards were approaching Peterhof, Peter made a desperate decision to sail Kronstadt, a fortress on an island. Upon arrival, Peter was refused admittance because all those in the fortress had sworn allegiance to Catherine. Peter rejected the advice of his advisors to go to the Prussian army and returned to Oranienbaum.

Peter and his Holstein guards were behind the gates at Oranienbaum and Alexei Orlov and his men had surrounded Oranienbaum. Peter sent a message that he would renounce the throne if he, his mistress Elizabeth Romanovna Vorontsova, and his favorite Russian general would be allowed to go to Holstein. Catherine sent Grigori Orlov with a Russian general to Oranienbaum insisting that Peter must write out a formal announcement of abdication in his handwriting. Orlov was to deal with the abdication and the general was to lure Peter out of Oranienbaum and back to Peterhof to prevent bloodshed. Orlov rode back to Peterhof with the signed abdication announcement and the general convinced Peter to go to Peterhof and beg Catherine for mercy. Upon arrival at Peterhof, Peter was arrested and taken by Alexei Orlov to Ropsha, a country estate outside of St. Petersburg.

Catherine II on a balcony of the Winter Palace on 28 June 1762, the day of the coup; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine had to deal with the same dilemma that Empress Elizabeth had to deal with regarding Ivan VI who she had deposed – keeping a former emperor around was a threat to her throne. Catherine intended to send Peter to Shlisselburg Fortress where Ivan VI had been imprisoned for more than twenty years. However, Catherine did not have to live with a living deposed emperor for long. The true circumstances of Peter’s death at the age of 34 on July 17, 1762, are unclear. It is possible Alexei Orlov murdered Peter. Another story is that Peter had been killed in a drunken brawl with one of his jailers. At the time, the official cause was “an acute attack of colic during one of his frequent bouts with hemorrhoids.” It is doubtful that Catherine played any role in Peter’s death. On July 19, 1762, Peter was buried without honors in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St. Petersburg.

Catherine’s coronation portrait by Vigilius Erichsen, circa 1765; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine II, Empress of All Russia crowned herself at the Assumption Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin on September 22, 1762. The Imperial Crown of Russia was created for her coronation and was used at the coronation for each subsequent Romanov emperor. The crown survived the Russian Revolution and the Soviet regime and is now displayed in the Moscow Kremlin Armory Museum. A photo of a copy of the crown is below.

Photo Credit – By Shakko – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30819221

During Catherine’s reign, Russia grew larger and stronger and was recognized as one of the great powers of Europe. The borders of the Russian Empire were significantly extended to the west and the south. Catherine reformed the government administration and many new cities and towns were founded on her orders. An admirer of Peter the Great, Catherine continued to modernize Russia along Western European lines. The economy continued depending on serfdom and the increasing demands of the state and private landowners led to increased reliance on serfs. This was one of the main reasons behind several rebellions during Catherine’s reign.

Russia finally became one of the great European cultural powers, promoted by Catherine herself. She was fond of literary activity, collecting masterpieces of painting and corresponding with French Enlightenment writers like Voltaire. The world-renowned Hermitage Museum, now occupying the whole Winter Palace, began as Catherine’s personal collection. The Smolny Institute, the first state-financed higher education institution for women in Europe, was established.

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin, Catherine’s great love; Credit – Wikipedia

Catherine never remarried and during her lifetime she had twelve lovers. After her disastrous marriage to her unbearable husband, Catherine wanted to love and be loved. Most long-term relationships ended after a few years. Only a few of her lovers were allowed to interfere in governmental affairs, although the others often tried. None of her lovers were persecuted or punished after their affairs were over. On the contrary, most of them received generous gifts from Catherine. Catherine gave birth to at least three children (listed above) and to a possible four others.

Catherine’s twelve lovers:

- Count Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov was Catherine’s first lover and probably the father of her son Paul. Their affair lasted from 1752 – 1754 while Catherine was still a Grand Duchess.

- Stanisław August Poniatowski became King of Poland through Catherine’s support. He was probably the father of her daughter Anna. Catherine’s affair with Poniatowski was from 1755 – 1757 while she was still a Grand Duchess.

- Count Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov was, along with his brother Alexei, instrumental in the fall of Catherine’s husband. He gave Catherine the famous Orlov Diamond which was used in the scepter of the Romanov rulers and was the father of at least one of Catherine’s children, Alexei Grigorievich Bobrinsky. Catherine and Orlov had a long-time relationship from 1759 – 1774, spanning the time Catherine was a Grand Duchess and Empress.

- Alexander Semyonovich Vasilchikov had a short relationship with Catherine from 1772 – 1774. After the affair, Vasilichikov said that he felt that he was treated like a male prostitute. Despite how he felt, he was given a substantial sum of money and several properties.

- Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin had a career in the civil service, was a member of the Imperial Council and president of the War College. Potemkin built the Black Sea Fleet and founded the cities of Sevastopol and Kherson. He is considered Catherine’s great love and the two could have secretly married. After a period of exclusivity, Grigory and Catherine worked out a new relationship that preserved their affection toward each other and their political collaborations but allowed each of them to choose other sexual partners. Their relationship lasted from 1774 until Potemkin’s death in 1791.

- Peter Vasilievich Zavadovsky was one of a series of short-term lovers Catherine had during the period she was still involved with Potemkin. He was Catherine’s lover from 1776-1777. Zavadovsky was jealous and demanded that Catherine give him exclusive intimacy. Potemkin, who had initially approved of Zavadovsky, asked for his removal. To make his point, he stayed away from Catherine’s birthday celebrations. Eventually, Potemkin got his way. In the summer of 1777, Zavadovsky was asked to leave the palace.

- Semyon Gavrilovich Zorich was introduced into the Russian court by Grigory Potemkin as a foil against Peter Zavadovsky. Zorich was another short-term lover from 1777 – 1778.

- Ivan Nikolaevich Rimsky-Korsakov was another short-term lover (1778 – 1779) introduced to Catherine by Potemkin In 1779, Catherine caught him being unfaithful with one of her ladies-in-waiting. Rimsky-Korsakov and the lady-in-waiting both lost their places at court.

- Alexander Dmitrievich Lanskoy was an aide-de-camp of Grigory Potemkin in 1779 and was introduced by Potemkin to Catherine in 1780. Lanskoy’s relationship with Catherine lasted until his death from diphtheria in 1784.

- Alexander Petrovich Yermolov was Catherine’s lover from 1785 – 1786. He was also introduced by Grigory Potemkin. Yermolov lost his position after unsuccessfully collaborating with enemies of Potemkin to have him removed.

- Count Alexander Matveyevich Dmitriev-Mamonov was Catherine’s lover from 1786 to 1789. Potemkin introduced Dmitriev-Mamonov to Catherine, hoping that he would care for her during his frequent absences due to government business. Dmitriev-Mamonov fell out of favor when he began an affair with a sixteen-year-old lady-in-waiting but Catherine treated him kindly until her death.

- Prince Platon Alexandrovich Zubov was Catharine’s last lover and the most powerful man in Russia during the last years of her reign. He was only 29-years-old at the time of Catherine’s death, 38 years younger than her. Their relationship lasted from 1789 until Catherine’s death in 1796.

Catherine and her son and heir, the future Paul I, maintained a distant relationship throughout her reign. Paul had been taken by his great-aunt Empress Elizabeth and raised under her supervision. Even after the death of Empress Elizabeth, Paul’s relationship with Catherine hardly improved. Paul’s early isolation from his mother created a distance between them which later events would reinforce. She never considered inviting him to share her power in governing Russia. Once Paul’s son Alexander (the future Alexander I, Emperor of All Russia) was born, it appeared that Catherine had found a more suitable heir. It is possible that Catherine intended to bypass Paul and name her grandson Alexander as her successor.

Catherine II; Credit – Wikipedia

On November 4, 1796, Catherine attended an evening assembly but left early because she felt slightly ill. The next day she seemed better and met with some of her counselors and her lover Zubov. She excused herself to use the toilet in her dressing room. When she did not return, her valet went to check on her and found her unconscious on the floor. Her face appeared purplish, her pulse was weak, and her breathing was shallow and labored. The court physician determined that Catherine had suffered a stroke. Despite all attempts to revive her, she fell into a coma from which she never recovered. Catherine II (the Great), Empress of All Russia died on November 6, 1796, at the age of 67 and after a reign of 34 years.

Immediately after the death of Catherine II, on the orders of her son and successor Paul I, Emperor of All Russia, the remains of Catherine’s husband, the deposed and murdered Peter III, Emperor of All Russia, were transferred first to the Grand Church of the Winter Palace and then to the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg, the burial site of the Romanovs. 60-year-old Alexei Orlov, who had played a role in deposing Peter III, was made to walk in the funeral procession, holding the Imperial Crown as he walked in front of the coffin. Peter III was reburied in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg at the same time as the burial of his wife Catherine II. Peter III had never been crowned so at the time of his reburial, Paul I personally performed the coronation ritual on Peter III’s remains. Ironically, Paul I, Emperor of All Russia suffered a fate similar to Peter III. Paul’s reign lasted five years, ending with his assassination by conspirators.

In 1767, five years after she came to the throne, the Legislative Assembly voted to name her Catherine the Great but she refused. Later in her reign, when she was again called Catherine the Great, she replied, “I beg you no longer to call me Catherine the Great because my name is Catherine II.” After her death, Russians began speaking of her as Catherine the Great and we still call her that today.

After the death of her lover Prince Grigory Potemkin in 1791, Catherine wrote the following idealized and modest epitaph for herself:

HERE LIES CATHERINE II

- Born in Stettin on April 21, 1729.

- In the year 1744, she went to Russia to marry Peter III. At the age of fourteen, she made the threefold resolution to please her husband, Elizabeth, and the nation. She neglected nothing in trying to achieve this. Eighteen years of boredom and loneliness gave her the opportunity to read many books.

- When she came to the throne of Russia she wished to do what was good for her country and tried to bring happiness, liberty, and prosperity to her subjects.

- She forgave easily and hated no one. She was good-natured, easy-going, tolerant, understanding, and of a happy disposition. She had a republican spirit and a kind heart.

- She was sociable by nature.

- She had many friends.

- She took pleasure in her work.

- She loved the arts.

The tombs of Catherine II and Peter III (back row) at the Peter and Paul Cathedral; Photo Credit – Автор: Deror avi – собственная работа, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8368144

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Romanov Resources at Unofficial Royalty

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Catherine the Great. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_the_Great [Accessed 19 Jan. 2018].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2018). Catherine II. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_II [Accessed 19 Jan. 2018].

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1981). The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias. New York, NY.: Doubleday

- Massie, R. (2016). Catherine the Great. London: Head of Zeus.

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Екатерина II. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%95%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B0_II#%D0%9B%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%8F_%D0%B6%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BD%D1%8C [Accessed 19 Jan. 2018].