by Emily McMahon and Susan Flantzer, revised May 2020

© Unofficial Royalty 2013

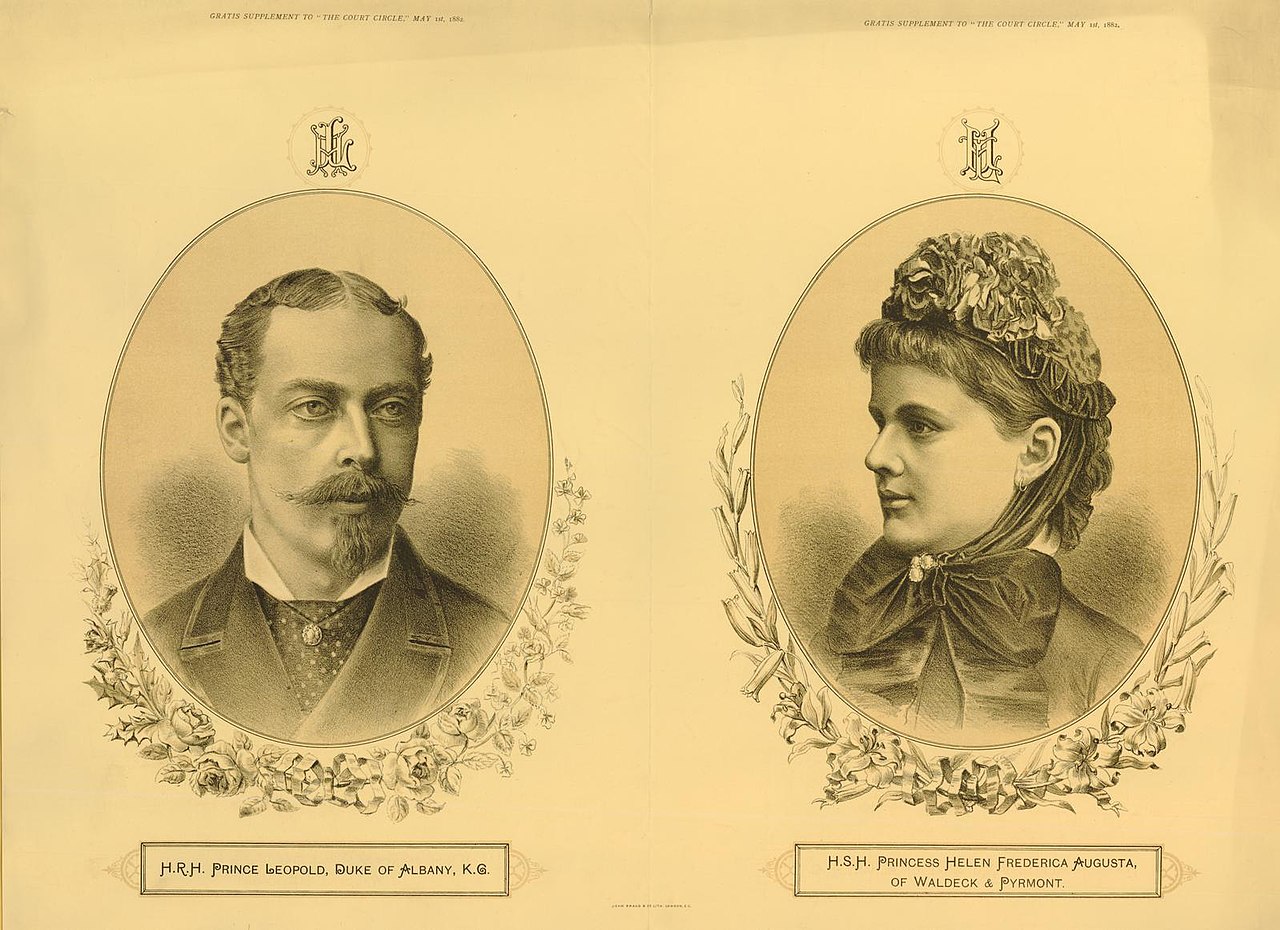

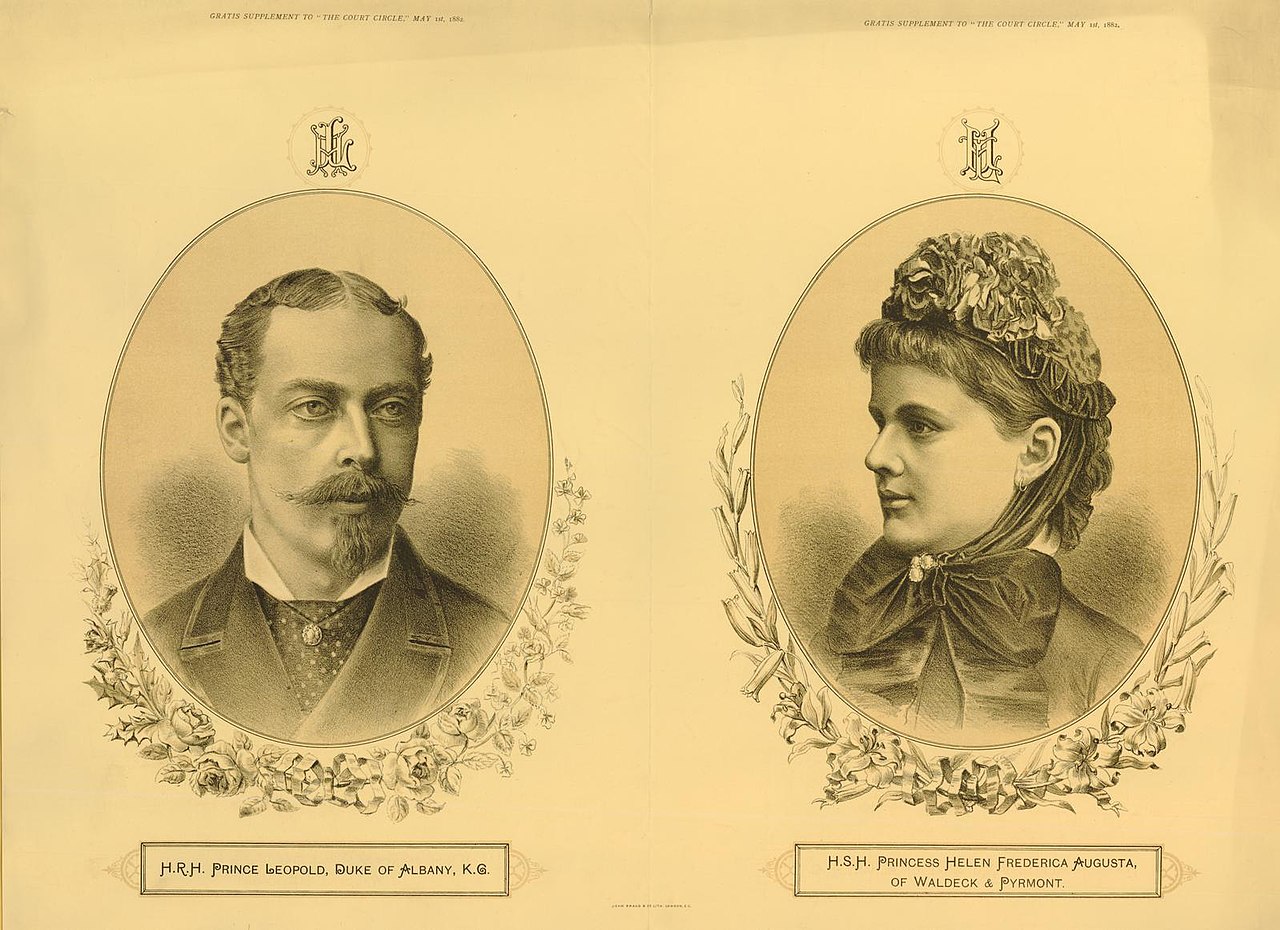

Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany and Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont; Credit – Wikipedia

Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, aged 29, and 21-year-old Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont were married on April 27, 1882, at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in Windsor, England. Sadly, Leopold and Helena’s marriage lasted only two years. The couple’s daughter Alice was born in 1883. Helena was pregnant with their second child when Leopold died on March 28, 1884, following a fall, apparently of a cerebral hemorrhage, the injuries having been exacerbated by his hemophilia. Their son Charles Edward was born several months after Leopold died in 1884. Charles Edward is the grandfather of King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.

Leopold’s Early Life

Prince Leopold at the University of Oxford in 1875; Credit – Wikipedia

Leopold was the eighth of the nine children and the fourth and youngest son of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. It became apparent that Leopold suffered from the genetic disease hemophilia and was the first of the nine hemophiliacs among Queen Victoria’s descendants.

Naturally, Leopold’s childhood activities were curtailed due to his hemophilia. He was perhaps Queen Victoria’s most intellectual child and had the artistic tastes of his father Prince Albert. Leopold somehow managed to convince his mother to allow him to spend four years (1872-1876) at Christ Church College, University of Oxford and he received an honorary doctorate in civil law in 1876. After Oxford, Leopold was involved in the patronage of various charitable organizations and also served as a secretary and advisor to his mother.

Helena’s Early Life

Princess Helena, circa 1880; Credit – Wikipedia

Helena was the fifth of six daughters and the fifth of the seven children of Georg Victor, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont and Helena of Nassau. Through both of her parents, Helena was a descendant of Anne, Princess Royal, the eldest daughter of King George II of Great Britain. Helena’s sister Princess Marie married Prince Wilhelm of Württemberg, later King Wilhelm II of Württemberg, but died in childbirth. Another sister, Princess Emma, married King Willem III of the Netherlands and had one child Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands.

Helena’s family lived mostly at Arolsen Castle, a Baroque-style home built during 1713-1728, in Arolsen, Principality of Waldeck and Pyrmont, now in Hesse, Germany. The Scottish philosopher, historian, and writer Thomas Carlyle was a great friend of Helena’s mother and a frequent visitor to Arolsen Castle. Carlyle described life at Arolsen Castle as a “pumpernickel court.” Helena had a Lutheran education from a very liberal-minded pastor.

The Engagement

Prince Leopold and Princess Helena in 1882; Credit – Wikipedia

Leopold saw marriage as a way to become independent from Queen Victoria, his overbearing mother. Besides having hemophilia, Leopold also had mild epilepsy. Although hemophilia had more serious consequences, it was a disease that was not completely understood at the time, and it was Leopold’s epilepsy that caused him problems while seeking a bride. Epilepsy was considered a social stigma and many families hid away their epileptic relatives.

After Leopold was rejected by several potential royal brides, Queen Victoria and her eldest daughter Victoria, Crown Princess of Prussia stepped in and made arrangements for Leopold and Helena to meet in Darmstadt, Grand Duchy of Hesse and by Rhine in September 1881 where Leopold was staying with Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, the widower of Leopold’s sister Alice. The two liked one another immediately, and after being briefed on Leopold’s health, the Waldeck-Pyrmont family had no objections to the marriage.

During a visit to Arolsen Castle, Helena’s home, Leopold and Helena became engaged on November 17, 1881. Leopold was ecstatic when he wrote of the news to his brother-in-law Ludwig, widower of his sister Alice: “…we became engaged this afternoon…Oh, my dear brother, I am so overjoyed, and you, who have known this happiness, you will be pleased for me, won’t you?… You only know Helena a little as yet – when you really know her, then you will understand why I’m mad with joy today.”

The Wedding Site

Embed from Getty Images

The wedding was planned for April 27, 1882, at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in Windsor, England. St. George’s Chapel was begun in 1475 by King Edward IV and completed by King Henry VIII in 1528. It is a separate building, located in the Lower Ward of Windsor Castle. The chapel seats about 800 people and has been the location of many royal ceremonies, weddings, funerals, and burials. Members of the Order of the Garter meet at Windsor Castle every June for the annual Garter Service which is held at St. George’s Chapel.

There had been no royal weddings at St. George’s Chapel until 1863 when Queen Victoria’s eldest son, the future King Edward VII, married Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Three other children of Victoria were also married at St. George’s Chapel: Princess Louise in 1871, Prince Arthur in 1879, and Prince Leopold in 1882.

Wedding Guests

CLICK TO ENLARGE The Marriage of the Duke of Albany, 27th April 1882 by Sir James Dromgole Linton; Credit – Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/404481/the-marriage-of-the-duke-of-albany-27th-april-1882

About the above painting from Royal Collection Trust: The Marriage of the Duke of Albany, 27th April 1882: Leopold, Duke of Albany (1853-1884), was the eighth child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He married Princess Helen of Waldeck and Pyrmont in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, in 1882. In the painting the bride and groom stand in front of the altar after their marriage. Queen Victoria stands on the right. She stated in her Journal that she wore for the first time ‘my own wedding lace over black satin, & my own wedding veil, which I had not worn since my wedding day in 1840, surmounted by my small diamond crown’. Sir Frederick Leighton was asked if he could suggest a rising young artist to paint a small picture of the wedding for Queen Victoria. She wanted ‘a simple representation of the group at the altar’. Leighton put forward Linton. Progress on the painting was slow, mainly because the artist had difficulty obtaining access to the dresses and uniforms worn by the participants. It was nearing completion in early 1884 when the Duke of Albany died of a brain haemorrhage and the painting that had begun as a celebration became a memorial. In December of that year the Queen described it as ‘not nearly finished, but promising to be good’, although she found the artist had been ‘very slow & tiresome’. The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1885. Signed and dated: JD Linton. 1885.

Special trains for the guests left Paddington Station in London for Windsor at 10:35 AM and returned from Windsor at 3:10 PM and 4:30 PM, and after the State Banquet at 11:00 PM. When the guests arrived at the Windsor train station, they proceeded in carriages to the South Entrance of St. George’s Chapel and were shown to the seats reserved for them by Her Majesty’s Gentlemen Ushers.

Royal Guests – The Groom’s Family

- Queen Victoria, mother of the groom

- The Prince of Wales, brother of the groom

- The Princess of Wales (Alexandra of Denmark), sister-in-law of the groom

- Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, brother of the groom

- The Duchess of Edinburgh (Marie Alexandrovna of Russia), sister-in-law of the groom

- Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, brother of the groom

- The Duchess of Connaught (Louise Margaret of Prussia) sister-in-law of the groom

- Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (Princess Helena), sister of the groom

- Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, brother-in-law of the groom

- Princess Louise, Marchioness of Lome, sister of the groom

- Princess Beatrice, sister of the groom

- Princess Louise of Wales, niece of the groom

- Princess Victoria of Wales, niece of the groom

- Princess Maud of Wales, niece of the groom

- Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, first cousin once removed of the groom

- The Duchess of Teck (Mary Adelaide of Cambridge), first cousin once removed of the groom

- The Duke of Teck, husband of Mary Adelaide of Cambridge

- Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, brother-in-law of the groom

- Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine, niece of the groom

- Ernst Leopold, 4th Prince of Leiningen, half-first cousin of the groom

- Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Augusta of Cambridge), first cousin once removed of the groom

- Friedrich Wilhelm, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, husband of Augusta of Cambridge

Royal Guests – The Bride’s Family

- Georg Victor, Reigning Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, father of the bride

- Princess of Waldeck and Pyrmont (Helena of Nassau), mother of the bride

- Princess Elisabeth of Waldeck and Pyrmont, sister of the bride

- Friedrich, Hereditary Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, brother of the bride

- King Willem III of the Netherlands, brother-in-law of the bride

- Queen Emma of the Netherlands (Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont), sister of the bride

Other Royal Guests

- Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar

- Maharajah Duleep Singh

- Maharanee Bamba, wife of Maharajah Duleep Singh

- Prince Philip of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

- Princess Philip of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Louise of Belgium), wife of Prince Philip

- Alexis, Hereditary Prince of Bentheim

Other Guests

- Charles Gordon-Lennox, 6th Duke of Richmond and Frances Gordon-Lennox, Duchess of Richmond

- William Beauclerk, 10th Duke of St. Albans and Grace Beauclerk, Duchess of St. Albans

- Francis Russell, 9th Duke of Bedford

- George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll and Amelia Campbell, Duchess of Argyll

- William Cavendish-Bentinck, 6th Duke of Portland

- Arthur Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington and Elizabeth Wellesley, Duchess of Wellington

- Countess of Dornburg, morganatic wife of Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar

- Countess Laura Gleichen, widow of the groom’s half first-cousin Prince Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg and her children Countess Feodora Gleichen and Count Edward Gleichen

- Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury and Georgina Gascoyne-Cecil, Marchioness of Salisbury

- Francis Seymour, 5th Marquis of Hertford and Emily Seymour, Marchioness of Hertford

- John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquis of Bute and Gwendolen Crichton-Stuart, Marchioness of Bute

- Caroline Loftus, Dowager Marchioness of Ely

- Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 6th Marquis of Londonderry and TheresaVane-Tempest-Stewart, Marchioness of Londonderry

- Henry Francis Conyngham, 4th Marquis Conyngham and Jane Conyngham, Marchioness Conyngham and Lady Jane Seymour Conyngham, sister of the 4th Marquis Conyngham

- Frances Butler, Dowager Marchioness of Ormond

- James Lindsay, 26th Earl of Crawford and Emily Lindsay, Countess of Crawford

- Alma Campbell, Countess of Breadalbane

- Katrine Cowper, Countess Cowper

- Robert St Clair-Erskine, 4th Earl of Rosslyn and Blanche St Clair-Erskine, Countess of Rosslyn

- Thomas Anson, 3rd Earl of Lichfield and Mildred Anson, Countess of Lichfield

- Charlotte Spencer, Countess Spencer

- Gertrude Browne, Countess of Kenmare

- George Greville, 4th Earl of Warwick and Anns Greville, Countess of Warwick and their daughter Lady Eva Greville

- Charles Yorke, 5th Earl of Hardwicke and Sophia Yorke, Countess of Hardwicke

- Nina Leveson-Gower, Countess Granville

- Florence Wodehouse, Countess of Kimberley

- Emily Townshend, Countess Sydney

- Edward Bootle-Wilbraham, 1st Earl of Lathom and Alice Bootle-Wilbraham, Countess of Lathom

- Lord Charles Fitzroy

- Lord Archibald Campbell

- Lord Ronald Leveson Gower

- Alexander Hood, 1st Viscount Bridport

- Hugo Charteris, Lord Elcho and Mary Constance Charteris, Lady Elcho

- Lady Marion Alford

- William Elphinstone, 15th Lord Elphinstone

- Lady Agneta Montagu, wife of Rear-Admiral The Honorable Victor Montagu

- Emily Cavendish, Lady Waterpark

- Colonel George Harris, 4th Baron Harris

- Paul Methuen, 3rd Baron Methuen

- Charles Cochrane-Baillie, 2nd Baron Lamington and Mary Cochrane-Baillie, Lady Lamington

- Montagu Corry, 1st Baron Rowton

- Baron Franz von Roggenbach, Grand Duchy of Baden politician

- The Honorable Sidney Herbert (later 14th Earl of Pembroke) and Lady Beatrix Herbert

- Admiral of the Fleet The Honorable Sir Henry Keppel

- The Honorable Mrs. Charles Grey and Miss Grey

- Sir Stafford Northcote (later 1st Earl of Iddesleigh) and Lady Northcote.

- Sir R. A. Cross (later 1st Viscount Cross)

- General Sir William Knollys

- The Honorable Mrs. Gerald Wellesley, wife of The Honourable and Very Reverend Gerald Wellesley, Dean of Windsor

- Colonel The Honorable A. Liddell

- The Honorable Lady Petty

- The Honorable Lady Biddulph

- The Honorable Lady Ponsonby and Miss Ponsonby, wife and daughter of Major-General Sir Henry Frederick Ponsonby, Private Secretary to Queen Victoria

- Sir Rainald Knightley, 3rd Baronet and Lady Knightley

- Sir Coutts Lindsay of Balcarres and Lady Lindsay of Balcarres

- Sir William Jenner, Baronet, M.D., Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria

- Sir James Paget, Baronet, Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria

- Sir Archibald Campbell of Blythswood, 1st Baronet and The Honorable Lady Campbell of Blythswood

- General Sir Patrick Grant

- Sir Theodore Martin, K.C.B.

- General Sir Edward Shelby Smyth

- Lady Harcourt

- Colonel George Ashley Maude, Crown Equerry of the Royal Mews

- Mr. Frederick Gibbs, former tutor to The Prince of Wales and Prince Alfred

- Colonel W. G. Stirling.

- Mr. Francis Knollys, Private Secretary to The Prince of Wales

- Captain Binkes, Royal Netherlands Navy.

- Captain Thomson, Royal Navy

- Captain Welch, Royal Navy

- Staff Captain Alfred Balliston

- Captain A. G. Perceval

- Henry Liddell, Dean of Christchurch, Oxford, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University and Mrs. Liddell

- Richard Chenevix Trench, Dean of Westminster

- Reverend Henry Mildred Birch, Chaplain to The Prince of Wales

- Reverend Canon G. H. Connor, Chaplain in Ordinary to The Queen

- Reverend A. Campbell, Vicar of Crathie Church near Balmoral in Scotland

- Reverend Canon Robinson Duckworth, former tutor to Prince Leopold

- Reverend Canon Richard Gee, Chaplain in Ordinary to The Queen

- Reverend William Rowe Jolley, former tutor to Prince Alfred

- Reverend Canon George Prothero, Rector of Whippingham and Chaplain in Ordinary to The Queen

- Reverend John Tulloch, The Queen’s Chaplain for Scotland

- Dr. Henry Wentworth Acland, Physician in Ordinary to The Queen

- Mrs. Collins

- Mrs. Childers

- Mr. Walter Campbell of Blythswood

- Madame de Arcos, friend of Empress Eugenie of France

- Dr. Wilson Fox, Physician Extraordinary to The Queen

- Mrs. Gladstone, wife of Prime Minister William Gladstone

- Mr. R. R. Holmes, Librarian at Windsor Castle

- Mr. Holzmann

- Mr. and Mrs. Coleridge Kennard

- Dr. Wickham Legg, Medical Attendant to Prince Leopold

- Mr. Augustus Savile Lumley, The Queen’s Queen Assistant Master of Ceremonies

- Miss Mackworth

- Mr. Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford

- Mr. F. Myers

- Mr. Whyte-Melville

- Mademoiselle Norelle, former French tutor to Queen Victoria’s children

- Dr. George Poore, former physician to The Prince of Wales

- Mrs. A. Royle

- Mr. Hermann Sahl, Librarian and German Secretary to Queen Victoria

- Mrs. Waller, British actress

- Mr. Arnold White, British journalist

- Sir Joseph Devereux, Mayor of Windsor

Guests in The Queen’s Gallery

- Mr. Doyne C. Bell, author

- Mr. Edward Henry Corbould, artist, instructor of historical painting to the royal family

- Dr. Francis Laking, Surgeon-Apothecary in Ordinary to The Queen

- Dr. William Ellison, Surgeon-Apothecary to The Queen’s Household

- Mr. S. Evans

- Mr. Charles Hallé, pianist and conductor

- Miss Jessie Ferrari, singer and music teacher

- Dr. William Hoffmeister, Surgeon-Apothecary to The Queen at Osborne House

- Dr. John Marshall, Private Physician in Attendance to The Queen

- Dr. Alexander Profeit, Estate Manager at Balmoral Castle

- Dr. James Reid, Physician in Ordinary to The Queen

The Queen’s Household – Guests and Participants in the Processions

- Mistress of the Robes – Elizabeth Russell, Duchess of Bedford

- Lady of the Bedchamber in Waiting – Susanna Innes-Ker, Dowager Duchess of Roxburghe

- Maids of Honour in Waiting – The Honorable Evelyn Paget, The Honorable Frances Drummond

- Bedchamber Woman in Waiting – The Honorable Lady Hamilton Gordon

- Lord Steward – John Townshend, 1st Earl Sydney

- Lord Chamberlain – Valentine Browne, 4th Earl of Kenmare

- Master of the Horse – Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster

- Private Secretary and The Keeper of the Privy Purse – General Sir Henry Ponsonby

- Treasurer of the Household – Gavin Campbell, 7th Earl of Breadalbane

- Comptroller of the Household – William Edwardes, 4th Baron Kensington

- Vice-Chamberlain – Lord Charles Bruce

- Gold Stick in Waiting – Field-Marshal Hugh Rose, 1st Baron Strathnairn

- Captain of the Gentlemen at Arms – Charles Wynn-Carrington, 3rd Baron Carrington

- Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard – William John Monson, 7th Baron Monson

- Master of the Buckhounds – Richard Boyle, 9th Earl of Cork

- Master of the Household – Major-General Sir John Cowell

- Lord in Waiting – John Ramsay, 13th Earl of Dalhousie

- Groom in Waiting – Colonel The Honorable. C. H. Lindsay

- Master of the Ceremonies – General Sir Francis Seymour, Baronet

- Clerk Marshal – General Lord Alfred Paget.

- Equerries in Waiting – Colonel The Honorable H. W. J. Byng, Captain A. J. Bigge.

- Groom of the Robes – Mr. Henry Erskine of Cardross.

- Silver Stick in Waiting – Lieutenant-Colonel Burnaby

- Field Officer in Brigade Waiting – Colonel G. H. Moncrieff

- Comptroller in the Lord Chamberlain’s Department -The Honorable Ponsonby Fane

- Pages of Honour – Mr. G. Byng, Mr. A. Ponsonby

- Gentlemen Ushers in Waiting – Mr. Algernon West, Mr. E. H. Anson, Captain N. G.Philips, Mr. A. Montgomery, Mr. Wilbraham Taylor

- Garter King of Arms – Sir Albert W. Woods

- Lancaster Herald – Mr. George Cokayne

- Chester Herald – Mr. H. Murray Lane

- Comptroller of the Household of Prince Leopold – Mr. R.H. Collins

- Equerries in Waiting to Prince Leopold – The Honorable Alexander Yorke, Captain Stanier Waller, Mr. A. Royle

- Lady in Attendance on Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont – The Honorable Mrs. Moreton

- Lord in Waiting to The Queen in Attendance on Princess Helena – George Byng, 7th Viscount Torrington

Guests – Ambassadors

- His Excellency The Turkish Ambassador and Madameisolle Musurus

- Count Georg Herbert Münster, His Excellency The German Ambassador and Countess Marie Munster

- Count Luigi Federico Menabrea, His Excellency The Italian Ambassador and Countess Menabrea

- Count Alajos Károlyi, His Excellency The Austro-Hungarian Ambassador and Countess Karolyi

- Prince Aleksey Borisovich Lobanov-Rostovsky, His Excellency The Russian Ambassador

- Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour, His Excellency The French Ambassador

- The Netherlands Minister and Countess de Bylandt

- The Belgian Minister

- Luís Pinto de Soveral, The Portuguese Minister

- Count de Sponneck, Secretary to the Danish Legation

- Count Piper, The Swedish Minister representing King Oscar II and Queen Sofia of Sweden

- Count von Seckendorff, representing The Crown Prince and Crown Princess of the German Empire and Prussia, the groom’s brother-in-law and sister

Guests – Government Officials

- Lord Chancellor – Roundell Palmer, 1st Baron Selborne

- Lord President of the Council – John Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer

- Lord Privy Seal – Chichester Parkinson-Fortescue, 1st Baron Carlingford

- Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer – William Gladstone

- Secretary of State for the Home Department – Sir William Harcourt

- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs – Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville

- Secretary of State for the Colonies – John Wodehouse, 1st Earl of Kimberley

- Secretary of State for War – Hugh C. E. Childers

- Secretary of State for India – Spencer Cavendish, Marquis of Hartington

- First Lord of the Admiralty – Thomas Baring, 1st Earl of Northbrook

- President of the Board of Trade – Joseph Chamberlain

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster – John Bright

- President of the Local Government Board – John Dodson

- Chief Secretary for Ireland – William Forster

- Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland – Francis Cowper, 7th Earl Cowper

- First Commissioner of Works – George Shaw-Lefevre

- Postmaster-General – Henry Fawcett

- Paymaster-General – George Glyn, 2nd Baron Wolverton

- Judge Advocate-General – George Osborne Morgan

- Vice-President of the Board of Education – A. J. Mundella

- Adjutant-General – Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Baron Wolseley

- Quartermaster-General – Lieutenant-General Arthur Herbert

- Military Secretary – Lieutenant-General Sir Edmund Whitmore,

- Earl Marshal – Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk

- Deputy Lord Great Chamberlain – Gilbert Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, 2nd Baron Aveland

- Speaker of the House of Commons – Henry Brand

Supporters and Bridesmaids

Leopold was supported by his eldest brother The Prince of Wales and his brother-in-law Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, the widower of his sister Alice.

Helena was supported by her father Georg Victor, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont and her brother-in-law Willem III, King of the Netherlands, the husband of Helena’s sister Emma.

Helena’s eight bridesmaids were unmarried daughters of Dukes, Marquises, and Earls:

- Lady Florence Anson (1860–1946), daughter of Thomas George Anson, 2nd Earl of Lichfield

- Lady Florence Bootle Wilbraham (died 1944), daughter of Edward Bootle-Wilbraham, 1st Earl of Lathom

- Lady Blanche Butler (1854–1914), daughter of John Butler, 2nd Marquess of Ormonde

- Lady Mary Campbell (1859 – 1947), daughter of George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll

- Lady Anne Lindsay (1858 – 1936), daughter of Alexander Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford

- Lady Ermyntrude Russell (1856–1927), daughter of Francis Russell, 9th Duke of Bedford

- Lady Alexandrina Vane-Tempest (1863 – 1945), daughter of George Vane-Tempest, 5th Marquess of Londonderry

- Lady Feodore Yorke (1864 -1934), daughter of Charles Yorke, 5th Earl of Hardwicke

The Wedding Attire

Embed from Getty Images

Leopold wore a Colonel’s uniform and used a cane to assist him in walking. He walked with a slight limp as he had injured his knee a few weeks earlier and his hemophilia had exacerbated the injury.

Helena’s dress, a gift from her sister Queen Emma of the Netherlands, was made by Madame Corbay of Rue Ménar in Paris. The gown was made of white satin, decorated with traditional orange blossom and myrtle and trimmed with fleur-de-lis. The bodice ended in a sharp V–shape and was swathed in tulle and ruched lace with a small bouquet of flowers. The shoulders were bare and on the short drop-sleeves were pinned the Royal Family Order of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert and the Companion of the Order of the Crown of India. The long tulle veil was held in place by a diamond headdress and a wreath of orange flowers and myrtle. The diamond necklace worn by Helena was a gift from Leopold.

The Wedding Ceremony

Embed from Getty Images

Vintage engraving of the Royal Wedding of Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany and Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont. Queen Victoria kissing the bride on the cheek. The London Illustrated News, 1882

Officiating Clergy

- Archibald Campbell Tait, Archbishop of Canterbury

- John Jackson, Dean of the Chapels Royal, Bishop of London

- Harold Browne, Prelate of the Order of the Garter, Bishop of Winchester

- John Mackarness, Chancellor of the Order of the Garter, Bishop of Oxford

- Henry Philpott, Clerk of the Closet, Bishop of Worcester

- The Honourable and Very Reverend Gerald Wellesley, Dean of Windsor, Lord High Almoner, Registrar of the Order of the Garter and Domestic Chaplain

Music

- Sir George Elvey, composer and the organist of St. George’s Chapel, presided at the organ and directed the orchestra and choir.

The Members of Her Majesty’s Household in Waiting who did not take part in the carriage processions from Windsor Castle, assembled at St. George’s Chapel at 11:30 AM arriving at the South Entrance. The clergy officiating at the wedding service gathered at the Deanery and took their places within the rails of the altar at 11:45 AM while a march was played on the organ.

At 11:45 AM, The Princess of Wales, the Royal Family, and the Royal Guests along with their attendants left the Quadrangle of Windsor Castle in carriages for the West Entrance of St. George’s Chapel. On arrival at the West Entrance, The Princess of Wales, the Royal Family, and the Royal Guests were received by The Lord Steward, John Townshend, 1st Earl Sydney and The Vice-Chamberlain of the Household, Lord Charles Bruce. The processions of The Princess of Wales, the Royal Family, and the Royal Guests made their way down the aisle to march by Sir George Elvey. As each procession moved from the entrance into St. George’s Chapel a Flourish of Trumpets was played by Her Majesty’s State Trumpeters stationed at the West Entrance.

At 12 noon, Queen Victoria accompanied by her youngest daughter Princess Beatrice and her granddaughter Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine, along with their attendants, left The Queen’s Entrance of Windsor Castle in carriages for the West Entrance of St. George’s Chapel. On arrival, they were met by The Lord Steward, John Townshend,1st Earl Sydney with The Treasurer of the Household, Gavin Campbell, 7th Earl of Breadalbane, The Comptroller of the Household – William Edwardes, 4th Baron Kensington, and The Vice-Chamberlain of the Household, Lord Charles Bruce. Her Majesty’s procession was conducted down the aisle by The Lord Chamberlain, Valentine Browne, 4th Earl of Kenmare as “Occasional Overture” by George Frederick Handel was played.

At 12:15 PM, the bridegroom Prince Leopold accompanied by his supporters, his eldest brother The Prince of Wales and Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine, his brother-in-law, the widower of Leopold’s sister Prince Alice, and their attendants, proceeded in carriages from The Queen’s Entrance of Windsor Castle to the West Entrance of St. George’s Chapel. On arrival, they were received by The Lord Chamberlain Valentine Browne, 4th Earl of Kenmare and The Lord Steward, John Townshend,1st Earl Sydney and their procession was conducted down the aisle as Felix Mendelssohn’s “March”, from Athalie was played. Prince Leopold was conducted to his seat on the right of the altar with his supporters standing next to him.

Immediately after the departure of the bridegroom, the bride Princess Helena accompanied by her supporters, her father Georg Victor, The Reigning Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, and her brother-in-law King Willem III of the Netherlands, and their attendants proceeded in carriages from The Queen’s Entrance of Windsor Castle to the West Entrance of St. George’s Chapel. On arrival, they were received by The Lord Chamberlain Valentine Browne, 4th Earl of Kenmare, and joined by the eight bridesmaids. The procession moved down the aisle to a “Special March” by French composer Charles Gounod, a friend of Prince Leopold who had asked Gounod to compose a piece of music for his bride’s procession down the aisle. The supporters of the bride stood near her and the bridesmaids stood behind her.

The wedding service was performed by Archibald Campbell Tait, Archbishop of Canterbury and the bride was given away by her father. At the conclusion of the wedding service, the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Ludwig Van Beethoven’s oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives was sung by the choir and a salute was fired in the Long Walk by a battery of artillery. Felix Mendelssohn’s now-famous “Wedding March” from his suite of Incidental Music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream was played as the royalty and their attendants left St. George’s Chapel by the West Door.

The Wedding Luncheon and Celebrations

On their return to Windsor Castle, the bride and groom signed the marriage register in the Green Drawing Room. Queen Victoria then signed the marriage register along with royalty and distinguished persons who had been invited to also do so. Queen Victoria and the bride and groom, accompanied by King Willem III and Queen Emma of the Netherlands, The Prince and Princess of Waldeck and Pyrmont and other royalty then proceeded to the State Reception Room to greet the guests who had assembled there.

Embed from Getty Images

Waterloo Gallery at Windsor Castle where the non-royal guests were served a buffet luncheon

Luncheon was privately served for Queen Victoria, the royal family, and the royal guests in the Dining Room. The other guests were served a buffet luncheon in the Waterloo Gallery. The bride and groom left for their honeymoon at 4:00 PM.

The wedding cake of the Duke and Duchess of Albany; Credit – Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/2905679/the-wedding-cake-of-the-duke-and-duchess-of-albany

The wedding cake was made by Her Majesty’s household confectioner. The cake, created in several layers, each separated by a dense icing for support and stacked upon the other to achieve its six-foot height, was entirely edible. The stacking technique was innovative for its day. Modern wedding cakes still use this method but because of the size of today’s cakes, internal support is added to each layer in the form of dowels.

In the evening, there was a State Banquet in St. George’s Hall presided by The Lord Steward, John Townshend, 1st Earl Sydney. The guests invited included the royal guests, ambassadors, members of the clergy, members of the government, members of The Queen’s Household, and other guests by special invitation. After the State Banquet, Queen Victoria and the guests proceeded to the Grand Reception Room where Her Majesty’s Private Band played in the Waterloo Chamber adjoining the Grand Reception Room. Later in the evening, there was a torchlit procession through the grounds of Windsor Castle. The torches made a letter “A” for Albany as Leopold was the Duke of Albany.

Torchlight procession for the marriage of Prince Leopold, 27 April 1882 by Sir Richard Rivington Holmes; Credit – Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/trails/royal-weddings/torchlight-procession-for-the-marriage-of-prince-leopold-7

The Honeymoon

Claremont House; Credit – By Heathermitch – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28583411

At 4:00 PM, the newlyweds, Their Royal Highnesses The Duke and Duchess of Albany,

attended by The Honorable Mrs. Moreton and The Honorable Alexander Yorke, left Windsor Castle for their honeymoon at Claremont House in Esher in Surrey, England escorted by a traveling escort of the 2nd Life Guards.

In 1816, Claremont House was bought by the British Nation by an Act of Parliament as a wedding present for the future King George IV’s daughter Princess Charlotte of Wales and her husband Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s uncle and the future Leopold I, King of the Belgians. After Princess Charlotte’s death in childbirth, her widower lived there until he became King of the Belgians, when he loaned the house to Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria, in turn, lent Claremont House to the exiled King and Queen of the French, Louis-Philippe and Marie-Amelie, who were the in-laws of King Leopold I via his second wife. Queen Victoria bought Claremont House from her first cousin Leopold II, King of the Belgians as a wedding gift for her son and daughter-in-law Leopold and Helena.

Leopold and Helena arrived in Esher around 6:00 PM, passing through a series of floral arches to a pavilion decorated with flowers. There they were greeted by the Rector of the local church and a group of local people. Leopold told them: “We both feel the greatest satisfaction in the thought that our first days of married life will be spent in the parish of Esher for it is here that we shall hope for the future to centre our local cares and interests.”

Unfortunately, Leopold and Helena’s honeymoon was marked by tragedy. Helena’s sister had married Prince Wilhelm of Württemberg, later King Wilhelm II of Württemberg. Marie was unable to attend the wedding because she was nine months pregnant. On April 24, 1882, Marie gave birth to a stillborn daughter, her third child, and suffered serious complications from childbirth. She died six days later, on April 30, 1882, and Helena went into the required period of mourning which limited her social interactions.

Children

Leopold and Helena had two children:

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Flantzer, Susan, 2013. Prince Leopold, Duke Of Albany. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/march-28-daily-featured-royal-date/> [Accessed 23 May 2020].

- Flantzer, S., 2014. Princess Helena Of Waldeck-Pyrmont, Duchess Of Albany. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/february-17-1861-birth-of-princess-helena-of-waldeck-pyrmont-wife-of-prince-leopold-duke-of-albany/> [Accessed 23 May 2020].

- Google Books. 1882. The Illustrated London News – Wedding Of Prince Leopold.

- Rct.uk. 2020. Sir James Dromgole Linton (1840-1916) – The Marriage Of The Duke Of Albany, 27Th April 1882. [online] Available at: <https://www.rct.uk/collection/404481/the-marriage-of-the-duke-of-albany-27th-april-1882> [Accessed 23 May 2020].

- The Gazette. 1882. Prince Leopold Wedding Page 1971 | Issue 25102, 2 May 1882 | London Gazett…. [online] Available at: <https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/25102/page/1971> [Accessed 23 May 2020].

- Van der Kiste, John, 2011. Queen Victoria’s Children. Stroud: The History Press.

- Zeepvat, Charlotte, 1999. Prince Leopold. Stroud: Sutton.