by Emily McMahon © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Photo Credit – 02varvara.wordpress.com

King Juan Carlos of Spain, whose title at the time was The Prince of Asturias, married Princess Sophia of Greece on May 14, 1962, in a Roman Catholic ceremony at the Cathedral of St. Denis in Athens, Greece, and then in a Greek Orthodox ceremony at the Metropolitan Orthodox Cathedral of the Virgin Mary also in Athens.

Juan Carlos’ Early Life

Juan Carlos, his father and his brother Alfonso in 1950; Credit – Wikipedia

Juan Carlos was born in Rome, Italy, on January 5, 1938, the eldest son of Infante Juan, Count of Barcelona and his second cousin, Maria de las Mercedes of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. The Count of Barcelona was considered an heir to the defunct Spanish throne at the time of his son’s birth. Born one month premature, Juan Carlos’ mother had been at the movie theater and his father hunting when labor began.

Juan Carlos joined his then 2-year-old sister Pilar in the nursery. Juan Carlos’ second sister Margarita followed in 1939, along with brother Alfonso in 1941. Although he was christened Juan Alfonso Carlos in honor of his father and grandfathers, he was known among his family as “Juanito,” the diminutive version of Juan. Like the majority of Spaniards, Juan Carlos was raised a Roman Catholic.

Born several years after the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic and the exile of the Spanish royals, Juan Carlos grew up mainly in Portugal, Switzerland, and Italy. Juan Carlos and Alfonso later continued their studies in Spain with the consent of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Juan Carlos completed his secondary schooling at the San Isidro Institute in Madrid.

In 1956, Juan Carlos’ life took a tragic turn when his younger brother Alfonso died after a shooting at the family’s home in Portugal. Stories began circulating that Juan Carlos had unintentionally killed his brother by firing the gun, unaware it was loaded. Juan Carlos’ role in Alfonso’s death (if he had one) has never been officially addressed, although by most accounts the death was accidental.

The Prince visited the United States in 1958, at which time Generalissimo Franco discussed reviving the Spanish monarchy following his own death. Although Franco regarded the Count of Barcelona with suspicion, he seemed to hold his son Juan Carlos in affection. The Count of Barcelona said he would never abdicate his claim to the throne to his son, and Juan Carlos said he would not accept the throne against his father’s wishes.

Juan Carlos served in the army, navy, and air force in Spain, and studied at the University of Madrid for a time, with a focus on economics and philosophy. He eventually became fluent in Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, and English and learned some Greek. Juan Carlos developed interests in hunting, waterskiing, golf, and car racing. During his young adulthood, he also collected records and cigarette lighters.

For more information about Juan Carlos see:

Sophia’s Early Life

Embed from Getty Images

Sophia was born in Psychiko, Greece, a suburb of Athens, on November 2, 1938. Sophia is the eldest child of Paul I, King of the Hellenes and his German-born wife, Frederica of Hanover. Sophia’s brother, the future King Constantine II, was born in 1940. Her sister Irene followed in 1943. Sophia was brought up in the Greek Orthodox faith.

Known within the family as Sophie, Sophia lived with her family in Egypt, Crete, and South Africa during World War II and the subsequent expulsion of the Greek monarchy from the country. The family returned to Greece in 1946.

Sophia was educated at the El Nasr Girls’ College in Alexandria while she lived in Egypt. Sophia later attended the Schloss Salem School in Salem, Germany, where her Hanoverian uncle George served as headmaster. After spending time as a student at Fitzwilliam College at Cambridge University, Sophia completed her education in Athens.

In 1958, Sophia visited the United States with her mother and brother. The family made appearances at several sites in numerous states during their month-long visit. During a stop in Quincy, Massachusetts, Queen Frederica christened a new oil tanker The Princess Sophie. The tanker was owned by Greek shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos, via one of his many companies. At the time, The Princess Sophie was the largest cargo ship ever built in the United States.

In 1960, Sophia served as an alternate to her brother on the Greek Olympic sailing team. The entire family traveled to Rome to see Constantine and the Greek sailing team win the Dragon class gold medal. Along with her native Greek, Sophia became fluent in her mother’s native language German, English, and later French and Spanish.

For more information about Sofia see:

Royal Romance

In an effort for young, suitable European royals to meet and mingle (and also to boost tourism in Greece), Sophia’s mother arranged a Mediterranean cruise on the Greek yacht Agamemnon in 1954. Several teenage and twenty-something royals were invited to tour a handful of Greek islands. Juan Carlos and Sophie were among the young royals on the cruise.

Common with young, marriageable royals of the time, Sophia and Juan Carlos were romantically linked with others early in their adulthood. Juan Carlos was rumored to be involved with Maria Gabriella of Italy, a daughter of former King Umberto II. He often spoke of Maria Gabriella in letters to friends, escorted her at weddings, and was photographed with her. Sophia’s name was frequently mentioned as a possible bride of the future King Harald V of Norway. There was also talk of Sophia marrying into one of the wealthy Greek ship-owning families.

However, by the summer of 1958, it appeared that Sophia and Juan Carlos were beginning to take a romantic interest in one another. At the wedding of Duchess Elisabeth of Württemberg and Antoine of Bourbon-Two Sicilies that July, Juan Carlos reportedly said that Sophia enchanted him. The two spent a much time together at the wedding celebrations, although he was officially the escort of Maria Gabriella.

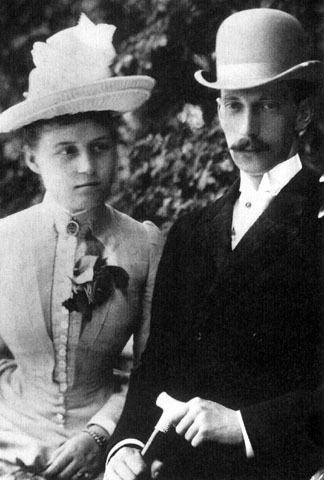

The families of Sophia and Juan Carlos reunited in Rome at the 1960 Olympic Games. The Greek royal family held a dinner for their Spanish guests onboard the ship Polemistis. At that point, Sophia and Juan Carlos had not seen each other for several months. During that time Juan Carlos had grown a mustache, which Sophia disliked on sight. She reportedly grabbed Juan Carlos’ hand, took him to the ship’s bathroom, and shaved off the mustache. Sophia later expressed surprise that he let her do it. Following the Olympics, Sophia’s family invited Juan Carlos and his family to spend Christmas 1960 with them in Corfu, Greece.

Sophia, Constantine, and Irene traveled to the United Kingdom in June 1961 to attend the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Kent. Due to a matter of protocol, Juan Carlos conveniently served as Sophia’s escort. Irene and Sophia were seen spending time with Juan Carlos at the wedding and various other events, which caught the eye of the press, encouraging rumors that Juan Carlos was courting one of the two sisters. Constantine acted as an unofficial chaperone for Sophia and Juan Carlos when the two attended several private events in London.

Following the success of the Kent wedding, Juan Carlos spent much of the summer of 1961 on Corfu at Mons Repos, the Greek royal summer home. Sophia later remarked that the two had several rather nasty arguments while sailing. She said it was during this trip that she decided marriage to Juan Carlos would be a viable option, as she felt if they could move past those arguments (which they did), they stood a chance at having a successful marriage.

Juan Carlos’ presence in Greece led to talk of him courting Sophia or Irene, but both families continued to officially deny the rumors. The Spaniards, in particular, wished to hide the news of the romance from Generalissimo Franco, whose relationship with Juan Carlos’ family had deteriorated in recent months.

The Engagement

Embed from Getty Images

The engagement was announced on September 13, 1961, during a dinner at the villa of Juan Carlos’ grandmother, former Queen Victoria Eugenie (Ena) in Lausanne, Switzerland. The parents of the bride and groom soon joined their children in Lausanne to mark the happy event.

At the villa, Sophia and Juan Carlos later met with members of the Swiss press to discuss the engagement. Juan Carlos said that he was not certain when he fell in love with Sophia, but that the couple had known each other for several years. Evidently, the two had surprised both sets of parents by indicating their wish to marry.

Reportedly, Juan Carlos popped the question to Sophia in a rather unusual way. While attending an event at the Beau Rivage Hotel in Lausanne, Juan Carlos said “Sofi, catch it!” while tossing a small box in her direction. Sophia did catch the box, and when she opened it she saw that it contained a ring made from melted ancient coins dating back to the reign of Alexander the Great. Juan Carlos then happily said, “Now we will get married, okay?” Years later, Sophia jokingly remarked that Juan Carlos never officially asked her to marry him.

Crown Prince Constantine, acting as regent of Greece during his father’s absence from the country, announced news of the engagement in Greece. According to Constantine, Paul was so excited by the news that he was unaware of the late hour (3:00 AM) when he called to share it with his son. Constantine himself said he was so thrilled by the news of the engagement that he had trouble going back to sleep.

In celebration of his sister’s engagement, Constantine provided Greek news editors with champagne at the royal palace in Athens the following day. A 21-gun salute was fired from nearby Mount Lycabettus to announce to the Greek public the upcoming marriage of their princess.

Juan Carlos and his mother left Lausanne the following day for Athens, traveling with Sophia and her family. Over 100,000 Greek citizens were waiting in the streets of Athens to welcome the new couple to the country.

Wedding Preparations

Embed from Getty Images

Due to Juan Carlos’ uneasy position in Spain, an Athens wedding was planned for May, the beginning of the tourist season in Greece. The celebrations involved 4 ½ months of nearly round-the-clock preparation headed by Colonel Dimitri Levidis, Grand Marshal of the Greek royal court. Colonel Levidis was in charge of every detail from the wording of the invitations to the exact timing of each ceremony. Because May was often a hot month in Greece, most of the official events connected with the wedding were scheduled indoors for the comfort of guests.

The difference in Juan Carlos’ and Sophia’s faiths posed questions on how the couple should be religiously married. In addition, Juan Carlos’ position regarding the restoration of the Spanish monarchy needed to be considered. While conversion to Catholicism was not required of Sophia to marry, the Spanish public would likely expect a future queen to be a practicing Catholic.

As such, a meeting was scheduled in November 1961, between Juan Carlos and a group of Spanish advisors at his home in Estoril, Portugal. The focus of the meeting was to discuss the best way to navigate the question of religion. Sophia began lessons in Spanish language, history, and geography. As a gesture of affection toward his fiancée, Juan Carlos simultaneously began learning the Greek language.

An estimated 5,800 hotel rooms were added in Athens in late 1961 and early 1962 in preparation for the wedding, predicted as the highlight of that year’s Greek tourist season. Officials also began seeking wealthy Greek citizens with extra space to house the influx of tourists and guests.

The wedding expenses were a major sticking point for many, with protests over the cost and the tradition surrounding Sophia’s $300,000 tax-free dowry. The opposition parties of the Greek Parliament abstained from voting on the dowry proposal but voiced displeasure on the “anachronistic and barbarous” practice of granting such monies, as well as expressed general criticism toward the royal family.

Sophia was seen at the Paris summer fashion season in January 1962 with her mother, sister, and Olga of Yugoslavia, herself a Greek princess and friend of Queen Frederica. The group was in Paris to view the collection of Jean Desses, the Paris-based designer hired to design Sophia’s dress and trousseau. Desses later remarked that the trousseau was not particularly costly or extensive as the Greek royal family was reported to be somewhat poor compared to their royal counterparts.

Celebrations in Athens

Three days of pre-wedding festivities began in Athens on May 10. Events included a garden party for 2,000 guests hosted by the parents of the couple. Spanish ambassador Marquis Luca de Tena held a gala for the couple in Athens the evening before the wedding. The gala featured Greek folk dancers performing in front of a large gathering of fellow royals and other prominent guests.

Prince Constantine took charge of the younger, unmarried adult royals attending the festivities, hosting a ball and sightseeing tours for up-and-coming royals. Members of the wealthy Athenian youth served as tour guides for the visitors.

Juan Carlos was observed as rather tense and gloomy during the celebrations. Unknown to most of the public, Juan Carlos was in severe pain. Less than a month before the wedding, he had broken his left collarbone while practicing judo with Prince Constantine. The sling had been removed just days before the parties began, but the pains in Juan Carlos’ arm and shoulder were still considerable.

Approval of the Churches

Embed from Getty Images

As Juan Carlos and Sophia were of different faiths, special consent was needed from both churches for the marriage to occur. A Greek Orthodox ceremony was required for the couple to be married in Greece, but the Spanish would likely not accept a future royal couple that had not been married according to Roman Catholic rites. The Duke of Edinburgh was asked to weigh in on his own experience converting from Greek Orthodoxy to the Church of England upon his marriage to Queen Elizabeth II.

After some discussion, an agreement was made to marry the couple in dual Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox ceremonies. The Catholic service would be held at the Cathedral of St. Denis, while the Orthodox ceremony would take place at the Metropolitan Orthodox Cathedral of the Virgin Mary in Athens.

Sophia signed a pledge issued by Pope John XXIII promising to raise any children in the Catholic faith and not to convert Juan Carlos to Orthodoxy. She also received instruction in Roman Catholicism, but at the time of the wedding, her own possible conversion to the faith was still officially in question. Shortly before the wedding, the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church gave their approval for the Orthodox ceremony.

Two days before the wedding, Sophia formally renounced her claim to the Greek throne. The renunciation was seen as a precursor to Sophia’s expected conversion to Roman Catholicism, as adherence to Greek Orthodoxy was required of Greek rulers. However, the Greek government had repeatedly expressed their opinion that should Sophia convert, she should not do so before leaving Greece.

Three weeks after the wedding, it was announced that Sophia would be converting to the Catholic faith. During a honeymoon visit in Rome, Pope John XXIII received the couple in celebration of the announcement and presented Sophia with a rosary.

Wedding Ceremonies

Embed from Getty Images

Very early on the morning of the wedding, several loads of fresh red roses were delivered to both the Catholic and Orthodox churches at the request of the bride and Queen Frederica. Over 35,000 roses alone decorated the Orthodox cathedral. Father Benedict Brindisi, Archbishop of Athens, and Chrystomos, Primate of Greece conducted the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox ceremonies respectively.

The Catholic ceremony was to be held first, scheduled for 10:00 AM on May 14, 1962. Sophia and her father traveled from the palace to the Cathedral of St. Denis in the same coach used for the 1908 wedding of George, Prince of Greece and Marie Bonaparte. The carriage was pulled by six white horses.

According to estimates by the Athens police, several hundred thousand (possibly up to one million) Greek and Spanish spectators packed the two-mile procession between the palace and both cathedrals. Upon arrival at St. Denis, Sophia was said to have seemed nervous and worried about the appearance of her train. However, before entering the cathedral, Sophia turned to wave at the excited spectators.

The cathedral was decorated with several thousand yellow and red roses and carnations in honor of the colors of Spain. While waiting at the altar at the beginning of the ceremony, Juan Carlos was said to be standing “ramrod-stiff”. Juan Carlos was addressed in Spanish during the ceremony, while Sophia was addressed in Greek.

Following the Catholic ceremony, Juan Carlos and Sophia rode together in state coach to the royal palace, while the guests headed to the Metropolitan Cathedral for the Orthodox service. After a very brief rest, Sophia and her father again rode from the palace to Orthodox cathedral via the same 1908 blue and gilt coach, while Juan Carlos traveled in a separate carriage with his mother.

The Orthodox service began at noon at the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Virgin Mary. As part of the Orthodox ceremony, attendants exchanged the rings and crowns worn by Juan Carlos and Sophia three times. The crowns were the same as those used during the wedding of Paul and Frederica in 1938.

Sophia smiled throughout both ceremonies, although she did shed some tears toward the end of the Orthodox service. Queen Frederica was also said to have cried during the service. Juan Carlos put his arm around and offered Sophia his handkerchief to comfort her. Not to be outdone by the Catholics, 22 Orthodox bishops assisted the Primate during the ceremony.

Upon leaving the Orthodox cathedral, a very excited Sophia nearly tripped over her long train. The couple descended the cathedral steps under a tunnel of swords held by eighteen Spanish officers, friends of Juan Carlos from the three Spanish military academies. Spanish royalists shouted, “Long live the King!” as the couple exited under a tunnel of swords. Sophia then threw her wedding bouquet, caught by Anne-Marie of Denmark, who married Sophia’s brother Constantine in 1964.

A short civil ceremony was held at the Greek Royal Palace following the religious services. Sophia would now be known as Sofia – the Spanish version of her name. A wedding banquet followed for guests attending the two religious ceremonies.

While most of the Greek public cheered the new couple with Greek and Spanish flags, the wedding was not universally popular. The heat of the wedding day also took a toll on several spectators. A 72-year-old Greek woman died of a heart attack during the festivities, and several others were treated for heat-related conditions.

Wedding Attire

Embed from Getty Images

Sophia wore a dress of silver lame covered in layers of heirloom Bruges lace and tulle. The dress was rather simple in design, with fitted three-quarter-length sleeves, a flared skirt, and a jewel neckline. The twenty-foot-long white lame and organza train extended from the neck of the dress.

The dress was designed by Jean Desses, a French designer of Greek heritage and a favorite of Queen Frederica. The choice of a designer located in neither Greece nor Spain caused an uproar, which Sophia attempted to soothe by requesting the dress be cut in Paris and assembled in Athens by a Greek seamstress. Desses also designed most of the pieces of Sophia’s trousseau.

Sophia’s veil consisted of fifteen feet of heirloom Bruges lace. Queen Frederica had worn the same veil when she married Paul of Greece in 1938. Sophia’s shoes, designed by Roger Vivier for Jean Desses, were also covered in lace. She carried a bouquet of lilies of the valley, a traditional wedding flower.

Sophia chose to wear the tiara now known as the Prussian Diamond Tiara or Hellenic Tiara. This tiara was originally gifted from German Emperor Wilhelm II to his daughter Viktoria Luise upon her marriage to Ernst Augustus of Hanover. Viktoria Luise then passed it to her daughter, Sophia’s mother Frederica upon her marriage into the Greek royal family. Frederica, in turn, gave the tiara to Sophia, as a wedding present. Very Hellenic in appearance, the platinum and diamond tiara features lines of pillars, Greek keys, and laurel surrounding an oval framing a single and free-hanging pear-shaped diamond.

The eight bridesmaids each wore a strapless dress of silver lame gauze. The skirt of the dress had many shallow pleats, which flared out the lightweight material. The dress was covered by a pastel silk faille top with three-quarter length sleeves and scoop necklines. Narrow ribbons tied into small bows just below the bust and at the waist created a cummerbund-style effect. The bridesmaids wore thick, braided headpieces that matched the dress and wore long white gloves during the ceremonies.

As he had served in all branches of the Spanish military, Juan Carlos had his choice of uniforms to sport on the wedding day, eventually wearing the olive green army uniform, possibly to please Generalissimo Franco. Like most royal grooms, Juan Carlos wore several of his many orders on his uniform. The Greek Order of the Redeemer was worn as the primary order, one of the oldest and most distinguished decorations awarded in Greece. Juan Carlos also wore several of his Spanish orders, including the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Order of Charles III.

Wedding Party

![]() Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Sophia chose a collection of eligible, young, European royal women born right around the beginning of World War II as her bridesmaids. The bridesmaids were:

- Anne of Orléans, a daughter of Henri of Orléans, Count of Paris and pretender to the French throne, and his wife Isabelle of Orléans-Braganza, a princess of the old Brazilian empire.

- Benedikte and Anne-Marie of Denmark, the two younger daughters of Frederik IX of Denmark and Ingrid of Sweden. Their elder sister Margrethe later became Queen of Denmark. Anne Marie also married Sophia’s brother Constantine in 1964.

- Tatiana Radziwiłł, a distant cousin of Sophia’s and the daughter of Eugenie of Greece and Polish prince Dominik Radziwiłł.

- Alexandra of Kent, a cousin of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom and a granddaughter of King George V.

- Irene of the Netherlands, the second daughter of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands and her consort, Bernhard of Schaumburg-Lippe. Irene was then a Spanish language student in Madrid. Her marriage two years later to Carlist pretender Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma caused considerable controversy in her home country.

- Pilar of Spain, the older sister of Juan Carlos.

- Irene of Greece, Sophia’s younger sister.

King Paul and several European princes served as crown bearers during the Orthodox service. Besides Paul, the crown bearers were:

- Crown Prince Constantine of Greece, Sophia’s younger brother.

- Michael of Greece, Sophia’s cousin.

- Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, a distant cousin of Juan Carlos and Sophia.

- Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden, a distant cousin of Sophia (and of Philip, Duke of Edinburgh).

- Victor Emmanuel, Prince of Naples, son of Umberto II of Italy.

- Don Marco Alfonso Torlonia, 6th Prince of Civitella-Cesi, a cousin of Juan Carlos.

- Christian of Hanover, Sophia’s uncle.

- Carlos of the Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Duke of Calabria, a distant cousin of Juan Carlos.

Michael and Amedeo doubled as Sophia’s witnesses for the civil wedding. In addition, two relatives of Juan Carlos, Alfonso of Orléans and Alfonso of Bourbon and Dampierre, served as his witnesses.

Wedding Guests

Embed from Getty Images

Many members of Europe’s ruling and non-ruling families attended the wedding. The guest list would be short for a royal wedding, given the capacities of the relatively small venues of the Cathedral of St. Denis and the Metropolitan Cathedral. Additionally, dignitaries, nobility, and other prominent non-royal guests needed to be accommodated. As a compromise, half of the royal guests would attend the Catholic wedding ceremony and the other half would attend the Orthodox service. Notable guests included:

- King Olav V of Norway

- Queen Ingrid of Denmark

- Prince Constantine of the Hellenes

- King Paul I and Queen Frederika of the Hellenes

- Queen Juliana of the Netherlands

- Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace of Monaco

- Princess Claude of Orléans

- Queen Juliana and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands

- Former King Umberto II and Queen Marie-Jose of Italy

- Former King Michael and Queen Anne of Romania

- Prince Franz Josef II of Liechtenstein

- Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg and Grand Duchess Josephine-Charlotte

- Henri and Isabella, Count and Countess of Paris

- Helen of Greece, former Queen Mother of Romania

- Victoria Eugenie (Ena) of Battenburg, former Queen of Spain

- Tomislav of Yugoslavia

- Louis Mountbatten, Earl Mountbatten of Burma

- Robert, Duke of Parma

- Alfonso, Duke of Calabria

- Luis of Orleans-Braganza, Prince Imperial of Brazil

- Ernest August V of Hanover

- Amadeo, Duke of Aosta

- Duarte Pio of Braganza

- Philip of Württemberg

- Philip of Hesse

- Marina, Duchess of Kent

- Franz of Bavaria

- Friedrich-Franz V of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Spanish naval minister Felipe Abarzuza y Oliva (official representative of Generalissimo Franco)

Wedding Gifts

Sophia and Juan Carlos received numerous wedding gifts from around the world. American President John F. Kennedy sent a golden cigarette box. Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco (later good friends of the new couple) provided a new sailboat (El Fortuna) and Greek shipping magnate George Goulandris gave the couple a yacht, both apt presents for gifted sailors.

From her family, Sophia received several gifts including a silver tea set, Greek silk bed linens, silverware, and a set of gold bracelets encrusted in gemstones. Juan Carlos’ parents gave Sophia a diamond and pearl tiara and pearl earrings. Even Generalissimo Franco showed his affection for the couple by gifting a diamond brooch. Sophia, likely aware of her new position in Spain, sent a personal letter of thanks to Franco.

Eager to take additional Greek-made items to her new home, Sophia was happy to receive various local crafts from areas around the country. Aside from the Goulandris yacht, Juan Carlos and Sophia were also received gifts of smaller watercraft and cars from Greek shipping tycoons. When by an agricultural organization asked for her choice of a wedding gift, Sophia requested a laurel tree planted at the couple’s future home to remind her of her home in Greece.

Generalissimo Franco and the Wedding

Generalissimo Francisco Franco announced before the ceremony that the Spanish monarchy would likely one day be restored following his rule. The wedding and Sophia’s conversion to Roman Catholicism added fuel to the rumors that the succession would pass the Count of Barcelona in favor of Juan Carlos and Sophia. Monarchists were said to happily approve of a union between their prince (and likely heir) and a royal princess of a ruling house.

Franco declined an invitation to the wedding, instead sending his naval minister Felipe Abarzuza y Oliva. Franco further allowed ample press coverage of the wedding, an action viewed as highly unusual and encouraging to monarchists. Two major newspapers were allowed to publish full front-page photos of the couple with accompanying articles. A third newspaper carried front-page articles on the wedding, while photographs of the event were shown on state television.

In celebration of the wedding, Generalissimo Franco bestowed the Collar of the Order of Charles III on both Juan Carlos and Sophia. This honor was and still is typically given only to Spanish monarchs.

Franco permitted only one photo of the Count of Barcelona to be published in Spain, which was placed in the newspaper’s classified ads. At the time of the wedding, reports of Franco bypassing the Count of Barcelona and naming Juan Carlos as his successor were still seen as highly unlikely.

The Honeymoon

Embed from Getty Images

A few weeks after the wedding, Juan Carlos and Sophia set out on a cruise of several Greek islands aboard the Greek yacht Eros, followed by a much longer trip around the world. The two made stops in Greece, Spain, Monaco, Italy, India, Thailand, the United States, and Japan. President Kennedy wished the couple good luck during a visit in August 1962. The honeymoon lasted several months as talks between Generalissimo Franco and the Count of Barcelona took place on the future of the Spanish monarchy. No final decision had been made when the couple returned in the late summer of 1962, forcing the two to embark on several extended stays with relatives in Switzerland, Portugal, and Greece as they had no permanent home.

New Couples

A gathering of such a large number of reigning and non-reigning European royals often resulted in talk of “who’s next” to be married. These types of rumors had followed royal weddings for decades. As so many of the participants in Sophia’s and Juan Carlos’ wedding were young, prominent, and eligible royals, the gossip mill was ripe in the following weeks and months. Eventually, there was a surprising amount of bona fide new royal couples. This included a set of sisters who became reacquainted with their respective new husbands during the wedding events.

Irene of the Netherlands was already a student in Spain when she was asked to serve as a bridesmaid for Sophia. Carlos Hugo of Bourbon-Parma, a son of the Carlist pretender to the Spanish throne may have met Irene at the wedding (or shortly before it) and the couple began to see one another not long after. Irene’s conversion to Catholicism and marriage to Carlos Hugo in 1964 created enormous controversy in the bride’s home country. Objectors pointed to years of Spanish rule of the Netherlands by Spain, fears of Generalissimo Franco’s regime, and Irene’s proximity to the throne. No one from the Dutch royal family attended the wedding and Irene gave up her succession rights. The couple had four children, but separated in 1980 and divorced the following year.

Bridesmaid Anne of Orléans became reacquainted with a childhood friend (and crown bearer) Carlos, Duke of Calabria during their involvement with Sophia’s and Juan Carlos’ wedding. The couple married in 1965 and had five children and eighteen grandchildren.

Anne’s sister Claude began seeing another crown bearer, Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, shortly after the wedding. The couple announced their engagement in 1963 and married the following year. Claude and Amedeo had three children before separating in the mid-1970s and divorcing a few years later.

Sophia’s brother Constantine had become acquainted with Anne-Marie of Denmark (another bridesmaid) during a state visit to Denmark a few years before. He had expressed interest in eventually marrying Anne-Marie shortly before the Spanish-Greek wedding, and the two spent a great deal of time together during the festivities. The engagement was announced in early 1963 when Anne-Marie was just sixteen. Constantine and Anne-Marie were married in September of 1964, just weeks after her eighteenth birthday.

Children

Juan Carlos, Sofia and their family in 1976; Photo Credit- http://www.casareal.es

Juan Carlos and Sofia had two daughters and one son:

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.