by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2021

Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg, Queen of Denmark and Norway; Credit – Wikipedia

The wife of Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway, Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg was born on July 9, 1511, at Lauenburg Castle in Lauenburg, Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg, now in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. She was the second of the six children and the eldest of the five daughters of Magnus I, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg and Catherine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.

Dorothea had five siblings:

- Franz I, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg (1510 – 1581), married Sibylle of Saxony, had nine children

- Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513 – 1535), married (first wife) King Gustav Vasa I of Sweden, had one son King Eric XIV of Sweden, fell while pregnant with her second child and died as did her child

- Clara of Saxe-Lauenburg (1518 – 1576), married Franz, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, had two children

- Sophia of Saxe-Lauenburg (1521 – 1571), married Anton I, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, had six children

- Ursula of Saxe-Lauenburg (circa 1523 – 1577), married (third wife) Heinrich V, Duke of Mecklenburg, no children

King Christian III of Denmark and Norway; Credit – Wikipedia

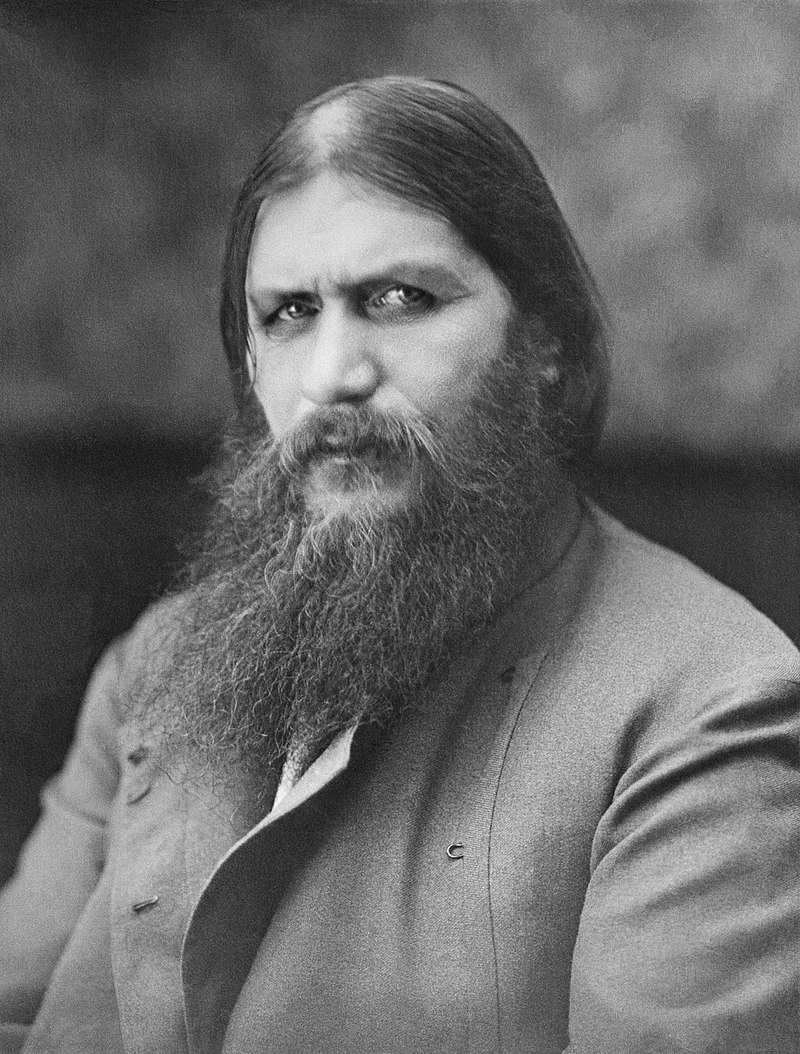

Dorothea’s homeland, the Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg, was one of the first states of the Holy Roman Empire to accept the Protestant Reformation, and Dorothea came to her marriage as a Lutheran. On October 29, 1525, in Lauenburg, fourteen-year-old Dorothea married the twenty-three-year-old future King Christian III of Denmark and Norway, son of Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway and his first wife Anna of Brandenburg.

Dorothea’s dowry of 15,000 guilders was considered extremely small. The groom’s father Frederik I, who had only reluctantly given his permission to the marriage, did not attend the wedding. Frederik I was the last Roman Catholic Danish monarch. All subsequent Danish monarchs have been Lutheran. Christian already had Lutheran views and, as King, would turn Denmark Lutheran. Perhaps, Frederik I’s refusal to attend his son’s wedding was due to religion and the small dowry. Dorothea and Christian initially lived in Hadersleben, now Haderslev, Denmark, where Christian resided as governor of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

Dorothea and Christian had five children:

- Anna of Denmark (1532 – 1585), married August, Elector of Saxony, had fifteen children

- Frederik II, King of Denmark and Norway (1534 – 1588), married Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, had seven children including Christian IV, King of Denmark and Norway and Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI, King of Scots, later also King James I of England

- Magnus of Denmark, Duke of Holstein (1540 – 1583), married Maria Vladimirovna of Staritsa, had two children

- Hans II, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg (1545 – 1622), married (1) Elisabeth of Brunswick-Grubenhagen, had fourteen children (2) Agnes Hedwig of Anhalt, had nine children

- Dorothea of Denmark (1546 – 1617), married Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, had fifteen children

After a reign of ten years, Christian’s father Frederik I, King of Denmark and Norway died on April 10, 1533. However, because of religious differences caused by the Reformation, a power struggle ensued regarding the succession. This resulted in a two-year civil war, known as the Count’s Feud, from 1534 – 1536, between Protestant and Catholic forces, which led to Christian ascending the Danish throne as King Christian III. In 1537, Christian III was also recognized as King of Norway. On August 6, 1536, Dorothea and Christian made their official entry into Copenhagen, Denmark. Four days later, Dorothea rode a snow-white horse at the side of her husband to Copenhagen Cathedral where they were crowned King and Queen of Denmark. Two months later, Lutheranism was established as the Danish National Church.

King Christian III and Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg; Credit – Wikipedia

The relationship between Dorothea and Christian was a happy one. Christian trusted her and allowed her a great deal of influence. Contemporary accounts show her to have been politically active and to have participated in state affairs. Shortly after his succession to the throne, Christian III supported plans to have Dorothea appointed future regent of Denmark should their son, the future Frederik II, succeed to the throne while still a minor. However, these plans were defeated by the Danish State Council, particularly by Johan Friis, the Chancellor of Denmark, whom Dorothea strongly resented. Friis also prevented Dorothea’s admission to the Danish State Council after the death of her husband.

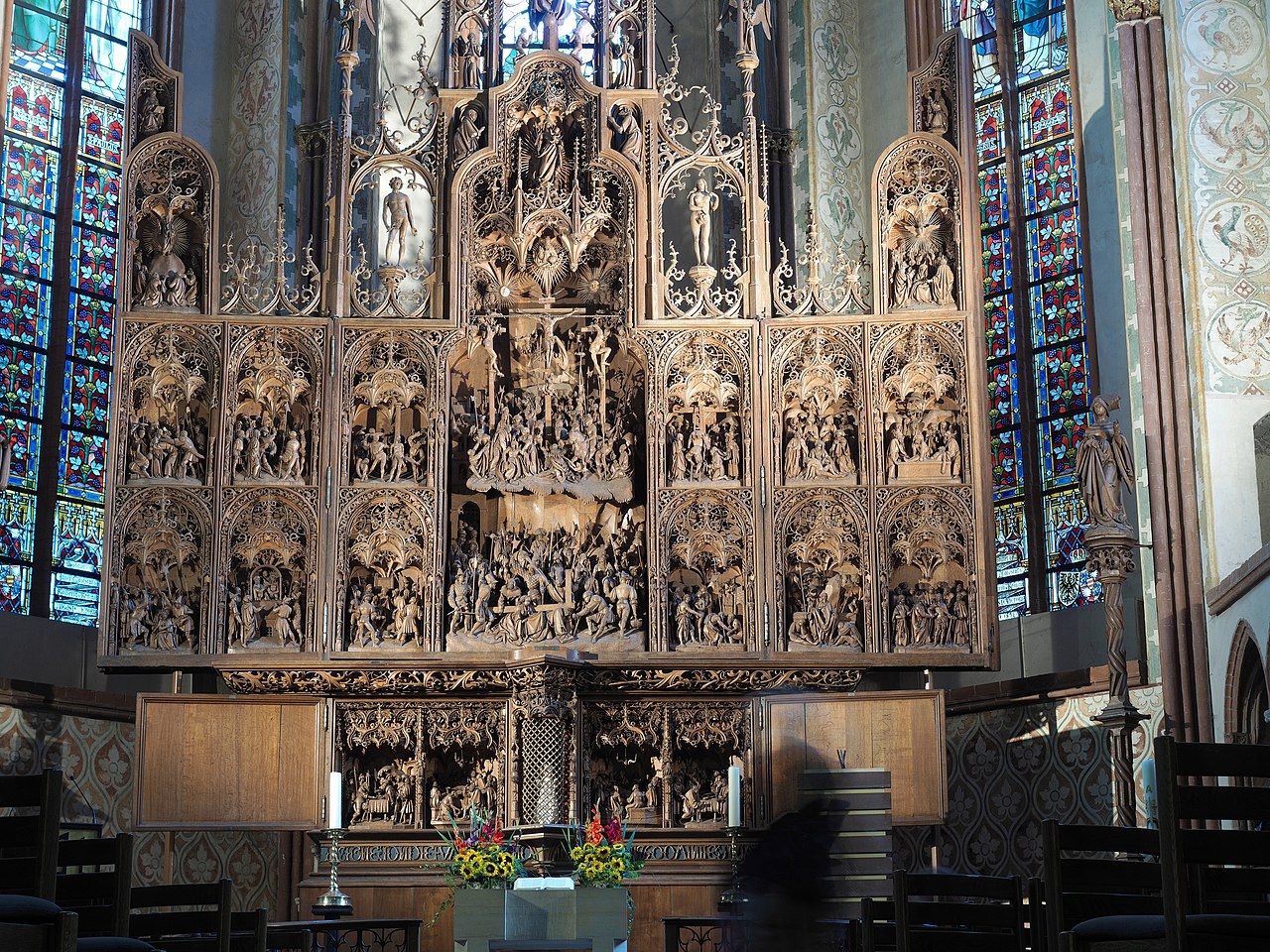

Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway died on January 1, 1559, aged 55, at Koldinghus, a Danish royal castle, on the Jutland Peninsula in Kolding, Denmark. He was buried in the Chapel of the Magi at Roskilde Cathedral in Roskilde, Denmark in a tomb designed by Flemish sculptor Cornelis Floris de Vriendt. His 25-year-old son succeeded him as Frederik II, King of Denmark and Norway. After Christian III’s death, Dorothea took over the management of Koldinghus, where she resided with her own court. She made annual trips to visit her daughters Anna, Electress of Saxony and Dorothea, Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

Shortly after Christian III’s death, Dorothea fell in love with Johann II, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev, Christian III’s unmarried half-brother from his father’s second marriage to Sophie of Pomerania. Johann was ten years younger than Dorothea and as early as 1559, there was talk of marriage. However, the marriage was opposed by various theologians who considered it impossible for a widow to marry her late husband’s brother and was eventually prevented, despite several years of efforts from Dorothea.

Dorothea’s son King Frederik II; Credit – Wikipedia

Dorothea and her son Frederik II had a tense relationship and she had always favored her younger sons Magnus and Hans. She had often used her parental authority to reprimand Frederik‘s lifestyle and this did not change after he became king. Frederik II detested his mother’s reprimands and attempts to be involved in state affairs as she had done during her husband’s reign.

During the Nordic Seven Years War (1563 – 1570), fought between Sweden and a coalition of Denmark, Norway, Lübeck, and Poland–Lithuania, the tension between Dorothea and her son Frederik II reached a breaking point. Dorothea was strongly against the war and repeatedly offered to act as a mediator because her nephew Eric XIV was King of Sweden. Frederik II warned his mother to stay out of state affairs. However, Dorothea continued her contact with Sweden. In 1567, Frederik II discovered that his mother had conducted secret negotiations, without his knowledge and during ongoing warfare, to arrange a marriage between his brother Magnus and Princess Sofia of Sweden, the half-sister of King Eric XIV of Sweden. Frederik II put a stop to the marriage plans. Although Dorothea told her son that she only intended to benefit Denmark and establish peace, in Frederik II’s mind, his mother had committed treason and she was informally exiled to Sønderborg Castle, where she lived the remainder of her life.

Tomb of King Christian III and Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg – Photo by Susan Flantzer

Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg, Queen of Denmark and Norway died on October 7, 1571, aged 60, at Sønderborg Castle in Sønderborg, Denmark. She was initially buried at the Sønderborg Castle Chapel (link in Danish). In 1581, her son Frederik II had her remains transferred to Roskilde Cathedral in Roskilde, Denmark where she was buried next to her husband King Christian III.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Kingdom of Denmark Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Kingdom of Denmark Index

- Danish Orders and Honours

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Oldenburg, 1448 – 1863

- Danish Royal Burial Sites: House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, 1863 – present

- Danish Royal Christenings

- Danish Royal Dates

- Danish Royal Residences

- Danish Royal Weddings

- Line of Succession to the Danish Throne

- Profiles of the Danish Royal Family

Works Cited

- Da.wikipedia.org. 2021. Dorothea Af Sachsen-Lauenburg. [online] Available at: <https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothea_af_Sachsen-Lauenburg> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Dorothea Of Saxe-Lauenburg. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothea_of_Saxe-Lauenburg> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

- Flantzer, Susan. 2021. Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway. [online] Available at: <https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/christian-iii-king-of-denmark-and-norway/> [Accessed 11 January 2021].