by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2020

Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe: In 1647, the County of Schaumburg-Lippe was formed through the division of the County of Schaumburg by treaties between the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, and the Count of Lippe. In 1808, the County of Schaumberg-Lippe was raised to a Principality and Georg Wilhelm, Count of Schaumburg became the first Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe.

At the end of World War I, Adolf II, the last Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe, was forced to abdicate on November 15, 1918, and lived out his life in exile. In 1936, Adolf II and his wife were killed in an airplane crash in Mexico. Today, the land encompassing the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe is in the German state of Lower Saxony.

********************

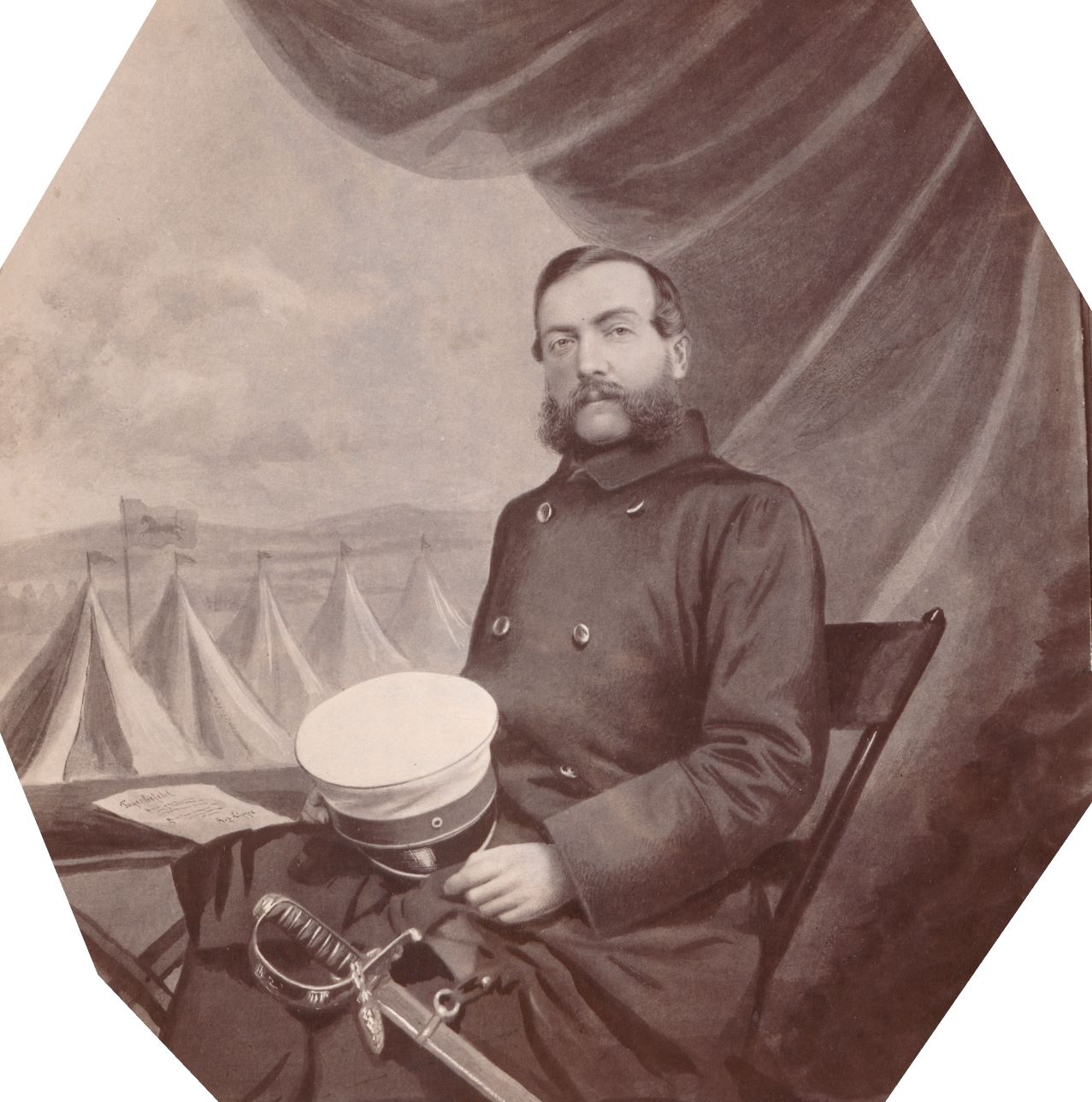

Adolf II, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe; Credit – Wikipedia

Adolf II (Adolf Bernhard) was the last reigning Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe. He was born on February 23, 1883, at Stadthagen Castle (link in German), the residence of the Hereditary Prince in Stadthagen, Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe, now in Lower Saxony, Germany. At the time of his birth, his father was the Hereditary Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe. Adolf was the eldest of the seven sons and the eldest of the nine children of Georg, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe and Princess Marie Anna of Saxe-Altenburg.

Adolf had eight younger siblings:

- Prince Moritz Georg of Schaumburg-Lippe (1884 – 1920), unmarried

- Prince Peter of Schaumburg-Lippe (born and died 1886), died in infancy

- Prince Wolrad of Schaumburg-Lippe (1887 – 1962), married his second cousin Princess Bathildis of Schaumburg-Lippe, had three sons and one daughter, Wolrad was Head of the House of Schaumberg-Lippe from 1938 until his death

- Prince Stephan of Schaumburg-Lippe (1891 – 1965), married Duchess Ingeborg of Oldenburg, had one son and one daughter

- Prince Heinrich of Schaumburg-Lippe (1894 – 1952), married Countess Marie-Erika von Hardenberg, had one daughter

- Princess Margareth of Schaumburg-Lippea (1896 – 1897), died in infancy

- Prince Friedrich Christian of Schaumburg-Lippe (1906 – 1983), married (1) Countess Alexandra zu Castell-Rüdenhausen, had two daughters and one son (2) Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, no children (3) Helene Mayr, no children

- Princess Elisabeth of Schaumburg-Lippe (1908 – 1933), married (1) Benvenuto Hauptmann, no children, divorced (2) Baron Johann Herring von Frankensdorff, had one son and one daughter

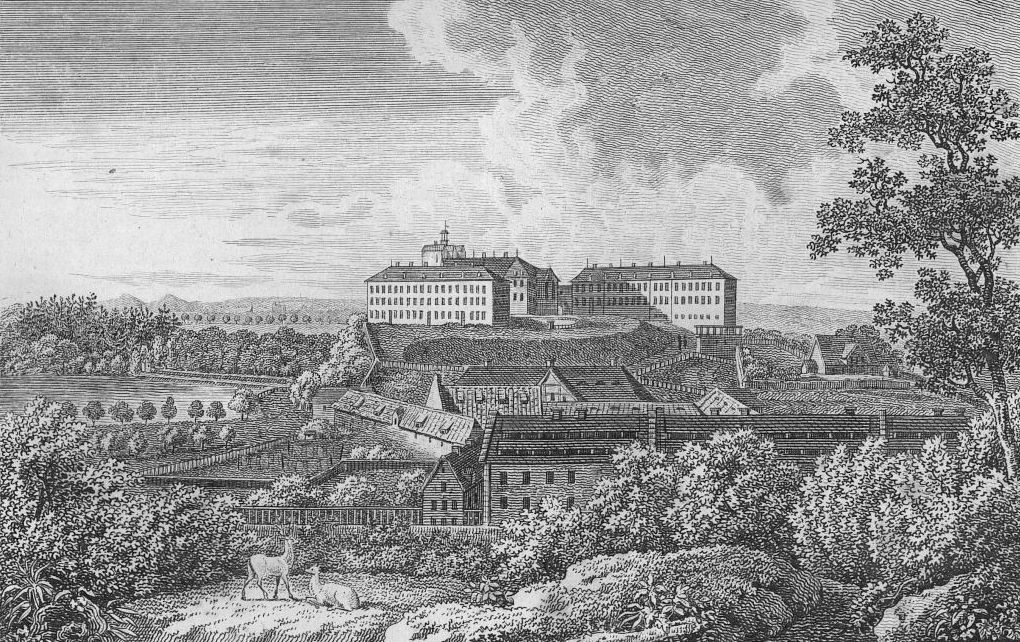

When his father died on April 29, 1911, Adolf became the reigning Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe. During Adolf’s reign, the huge Bückeburg Mausoleum (link in German) was built between 1911 and 1915 on the Bückeburg Palace grounds to replace the Princely Mausoleum at the St. Martini Church in Stadthagen (links in German) as the family burial site. Adolf’s father was the first in the family to be buried there. After the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, Adolf II was forced to abdicate on November 15, 1918, and the Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe became the Free State of Schaumburg-Lippe. Adolf was exiled from the Free State of Schaumburg-Lippe and lived in the Brionian Islands, then Italy, now in Croatia.

Ellen von Bischoff-Korthaus; Credit – Wikipedia

On January 10, 1920, in Berlin, Germany, Adolf married actress Elisabeth Franziska (Ellen) von Bischoff-Korthaus. Ellen was born on November 6, 1894, in Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, now in the German state of Bavaria. The marriage was childless. Adolf was not the first prince Ellen married. On August 24, 1918, Ellen married Prince Eberwyn of Bentheim and Steinfurt (1882 – 1949), son of Prince Alexis of Bentheim and Steinfurt and Princess Pauline of Waldeck and Pyrmont, daughter of George Victor, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont and his first wife Princess Helena of Nassau. The couple was divorced on December 13, 1919.

While living in Italy, Adolf and Ellen were investigated by the Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei, Secret State Police) beginning in June 1934. They were later denounced by Kurt von Behr, head of the Nazi Party in Italy.

On March 26, 1936, Adolf, aged 53, and his wife Ellen, aged 42, were killed in an airplane crash in Zumpango, Mexico, along with eight other passengers from Germany, Austria, and Hungary, and four crew members. Their plane developed engine trouble and crashed between the volcanoes Popocatepetl and Ixtaccihuatl as they were flying from Mexico City, Mexico to Guatemala City, Guatemala. The plane was chartered by Hamburg-American Line, which brought the Europeans to Mexico on a tour. It was the worst Mexican plane crash at that time.

The bodies of Adolf and Ellen were recovered and returned to Germany thanks to the intervention of Adolf’s youngest brother Friedrich Christian who was aide-de-camp to Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. Friedrich Christian joined the Nazi Party in 1928, one of the first German princes to do so. He never distanced himself from the Nazi ideology and championed it until the end of his life. Initially, Friedrich Christian was against the idea of burying Ellen’s remains in the Bückeburg Mausoleum because he thought that she was not of Aryan origin. When Friedrich Christian was proven wrong, Ellen was buried with Adolf at the Bückeburg Mausoleum (link in German) on the grounds of Bückeburg Castle. Wolrad, Adolf’s next surviving brother, who was also a member of the Nazi Party, succeeded him as Head of the House of Schaumburg-Lippe.

Bückeburg Mausoleum; Credit – Von Corradox – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7328133

Schaumburg-Lippe Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe Index

- Profiles: Princes and Consorts of Schaumburg-Lippe

- Schaumburg-Lippe Royal Burial Sites

Works Cited

- De.wikipedia.org. 2020. Adolf II. (Schaumburg-Lippe). [online] Available at: <https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_II._(Schaumburg-Lippe)> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. 2020. Adolf II, Prince Of Schaumburg-Lippe. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolf_II,_Prince_of_Schaumburg-Lippe> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

- It.wikipedia.org. 2020. Adolfo II Di Schaumburg-Lippe. [online] Available at: <https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolfo_II_di_Schaumburg-Lippe> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

- Pt.wikipedia.org. 2020. Adolfo II, Príncipe De Eschaumburgo-Lipa. [online] Available at: <https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolfo_II,_Pr%C3%ADncipe_de_Eschaumburgo-Lipa> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

- Timesmachine.nytimes.com. 1936. 14 Die In Worst Mexican Air Crash; Three Titled Germans Among Dead; Plane Carrying Ten Tourists From Europe And Four In Crew Falls Between Two Volcanoes, Killing All — Prince And Princess Adolf Of Schaumburg-Lippe Lose Lives. [online] Available at: <https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1936/03/27/87926235.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.