by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

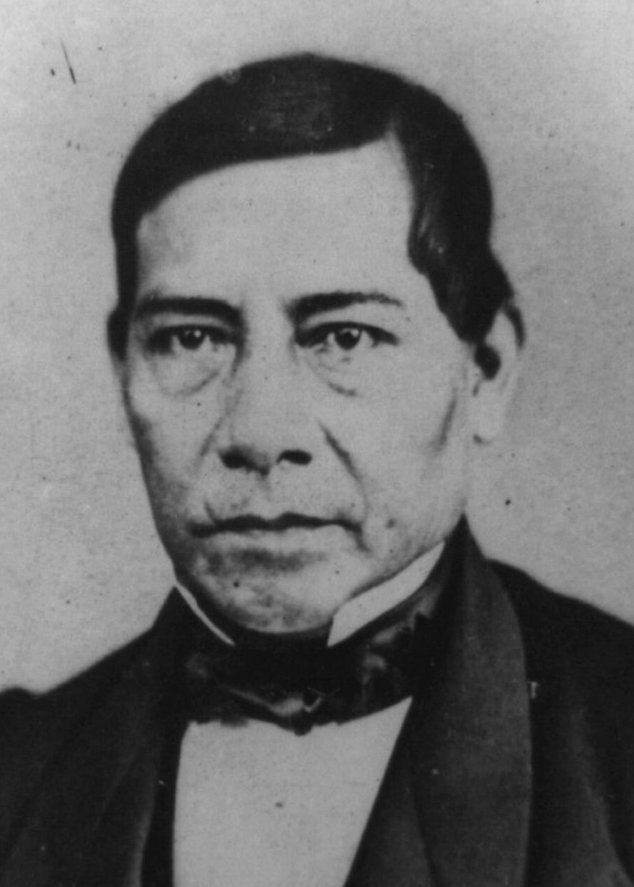

Ida of Schaumburg-Lippe; Credit – Wikipedia

Princess Ida Mathilde Adelheid of Schaumburg-Lippe, the wife of Heinrich XXII, 5th Prince Reuss of Greiz, was born on July 28, 1852, in Bückeburg, Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe, now in Lower Saxony, Germany. She was the fifth of the eight children and the third of the four daughters of Adolf I, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe and his first cousin Princess Hermine of Waldeck and Pyrmont, Ida and her sisters had a simple upbringing but were well-educated. They knew about how to run a household and could hold their own in discussions about philosophy and science.

Ida had four older siblings and three younger siblings:

- Princess Hermine of Schaumburg-Lippe (1845 – 1930), married Duke Maximilian of Württemberg (link in German), no children

- Georg, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe (1846 – 1911), his father’s successor, married Princess Marie Anne of Saxe-Altenburg, had seven sons and two daughters

- Prince Hermann of Schaumburg-Lippe (1848 – 1928), unmarried

- Princess Emma of Schaumburg-Lippe (1850 – 1855), died in childhood

- Prince Otto Heinrich of Schaumburg-Lippe (link in German) (1854 – 1935); married Anna von Koppen, had two sons and one daughter

- Prince Adolf of Schaumburg-Lippe (1859 – 1917), married Princess Viktoria of Prussia, daughter of Friedrich III, German Emperor and Victoria, Princess Royal, no children

- Princess Emma of Schaumburg-Lippe (1865 – 1868), died in childhood

Ida’s husband Heinrich XXII, 5th Prince Reuss of Greiz; Credit – Wikipedia

Note about the Reuss numbering system: All males of the House of Reuss were named Heinrich plus a number. In the Reuss-Greiz, Elder Line, the numbering covered all male children and the numbers increased until 100 was reached and then started again at 1. In the Reuss-Gera, Younger Line, the system was similar but the numbers increased until the end of the century before starting again at 1. This tradition was seen as a way of honoring Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VI (reigned 1191 – 1197) who had benefitted the family. Therefore, the Roman numerals seen after names are NOT regnal numbers.

On October 8, 1872, 20-year-old Ida married 26-year-old Heinrich XXII, 5th Prince Reuss of Greiz. Ida and Heinrich XXII had one son and five daughters. Their only son Heinrich XXIV would be unable to marry and be unable to rule because of his physical and mental disabilities as a result of an accident in his childhood. Heinrich XXIV would be nominally the 6th Prince Reuss of Greiz but two Regents from the House of Reuss-Gera (also called the Younger Line) successively ruled the Principality of Reuss-Greiz: Heinrich XIV, 4th Prince Reuss of Gera from 1901 – 1913 and then his son Heinrich XXVII, 5th and last Prince Reuss of Gera from 1913 – 1918, when the monarchy was abolished in 1918 at the end of World War I.

Ida’s son Heinrich XXIV, 6th Prince Reuss of Greiz; Credit – Wikipedia

Ida and Heinrich XXII’s children:

- Heinrich XXIV, 6th Prince Reuss of Greiz (1878 – 1927), unmarried

- Princess Emma Reuss of Greiz (1881 – 1961), married Count Erich von Ehrenburg, had one son and one daughter

- Princess Marie Reuss of Greiz (1882 – 1942), married Baron Ferdinand von Gnagnoni, no children

- Princess Caroline Reuss of Greiz (1884 – 1905), married Wilhelm Ernst, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, no children

- Princess Hermine Reuss of Greiz (1887 – 1947), married (1) Prince Johann Georg of Schoenaich-Carolath, had three sons and two daughters (2) Wilhelm II, former German Emperor and King of Prussia, no children

- Princess Ida Reuss of Greiz (1891 – 1977), married Prince Christoph Martin III zu Stolberg-Rossla (link in German), had two sons and two daughters

The five Reuss-Greiz sisters, left to right – Hermine, Ida, Marie, Caroline, and Emma; Credit – Wikipedia

From 1871 to 1873, Heinrich XXII built Jagdschloss Ida-Waldhaus, a hunting lodge in the forest near Greiz which he named after his beloved wife Ida. Heinrich XXII loved the tranquility of that forest so much that he decided to be buried there. In 1878, Heinrich XXII commissioned Eduard Oberländer, the master builder of Greiz, to build a Gothic-style chapel with a crypt. Completed in 1883, the Waldhaus Mausoleum (link in German) would first be used for Ida eight years later.

Waldhaus Mausoleum near Greiz; Credit – Wikipedia

Sadly, on September 28, 1891, Ida died, aged 39, from complications that occurred during the birth of her sixth child, a daughter, named Ida after her. Heinrich XXII wrote to his former mentor Baron Albert von der Trenk, “The sun of my earthly happiness set on September 28.” Ida was buried in the Waldhaus Mausoleum her husband had built in the forest near Greiz. When Ida’s husband Heinrich XXII died in 1902 and when their son Heinrich XXIV died in 1927, they were also buried in the Waldhaus Mausoleum. By 1969, the Waldhaus Mausoleum had fallen into disrepair and the remains of Heinrich XXII, Ida, and their son Heinrich XXIV were taken to Werdau Crematorium, cremated, and placed in urns. The urns were reburied at the Neue Friedhof (New Cemetery) in Greiz, Thuringia, Germany. Since 1997, the resting place of the urns has been at the Stadtkirche St. Marien (link in German) in Greiz.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Reuss-Greiz Resources at Unofficial Royalty

- Principality of Reuss-Greiz Index

- Profiles: Reuss-Greiz Rulers and Consorts

- Royal Burial Sites of the Principality of Reuss-Greiz

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Princess Ida of Schaumburg-Lippe. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Princess_Ida_of_Schaumburg-Lippe [Accessed 5 Mar. 2020].

- Flantzer, Susan. (2020). Heinrich XXII, 5th Prince Reuss of Greiz. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/heinrich-xxii-5th-prince-reuss-of-greiz/ [Accessed 5 Mar. 2020].

- It.wikipedia.org. (2020). Ida di Schaumburg-Lippe. [online] Available at: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_di_Schaumburg-Lippe [Accessed 5 Mar. 2020].