by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2020

On May 14, 1610, while his carriage was stopped on a Paris street, 56-year-old King Henri IV of France was stabbed to death by Catholic zealot François Ravaillac.

King Henri IV of France

King Henri IV of France; Credit – Wikipedia

King Henri IV of France was the first French king of the House of Bourbon. Born in 1553, in Pau, Kingdom of Navarre, now in France, Henri was the son of Queen Jeanne III of Navarre and Antoine de Bourbon, Duke de Vendôme. Although he was baptized in the Catholic Church, Henri was raised as a Protestant. His mother Queen Jeanne III of Navarre became a Calvinist Protestant, also known in France as French Huguenots, while Henri was a boy. She then became a spiritual and political leader of the French Huguenot movement.

Upon his mother’s death in 1572, Henri took the throne as King Henri III of Navarre. Two months later, he married Marguerite of Valois, the daughter of King Henri II of France. As Henri was a Protestant French Huguenot, he was not permitted inside Notre Dame Cathedral so the ceremony was held just outside the building. Days later, the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre took place, in which thousands of Protestant French Huguenots were killed. Henri narrowly escaped death, mostly thanks to his new Catholic wife, and his promise to convert to Catholicism.

In 1584, Henri became the heir-presumptive to the French throne, as the last heir to King Henri III of France had died. Henri was the senior agnatic descendant of King Louis IX, and therefore the rightful heir. King Henri III of France was assassinated on August 2, 1589, and King Henri III of Navarre, as the heir-presumptive, became King Henri IV of France. After several years of issues with French Catholic nobles who refused to recognize him as their new king and with the encouragement of his mistress Gabrielle d’Estrées, Henri once again renounced his religion and converted to Catholicism. This gained him the support of the French people and he was finally able to rule his kingdom.

In a loveless and childless marriage, and knowing that he needed an heir, Henri began negotiations to end his first marriage to Marguerite of Valois. In 1600, Henri married Marie de’ Medici, from the wealthy House of Medici that came to prominence in the 15th century, as founders of the Medici Bank in Florence, Tuscany, now in Italy. Henri and Marie had six children including King Louis XIII of France, Elisabeth who married King Felipe IV of Spain, Christine Marie who married Vittorio Amedeo I, Duke of Savoy (ancestors of the Kings of Italy), and Henrietta Maria who married King Charles I of England.

For more information, see Unofficial Royalty: King Henri IV of France.

********************

Roots of the Assassination

Despite Henri’s conversion to Roman Catholicism, along with his quote, “Paris is well worth a Mass,” hard-core Catholic zealots were not convinced of his sincerity. There were eighteen documented cases of attempted assassination or conspiracy to commit an assassination against Henri. In 1598, Henri issued the Edict of Nantes, which granted toleration to the French Huguenots. While Roman Catholicism remained the state religion, Huguenots were granted the reinstatement of their civil rights, including the right to work in any field or for the state and to bring grievances directly to the king. The Edict of Nantes restored peace and internal unity to France but pleased neither Catholics nor Protestants. Catholics rejected the recognition of Protestantism as a permanent element in French society. They still hoped to return to religious uniformity when Roman Catholicism was the only religion. Protestants wanted parity with Catholics in all matters.

********************

The Assassin

François Ravaillac; Credit – Wikipedia

François Ravaillac was born circa 1577-1589 in Angoulême, France. He was the youngest son of Jean Ravaillac, secretary-clerk of the mayor of Angoulême, and Françoise Dubreuil. His maternal uncles, Julien and Nicolas Dubreuil, were priests at Saint-Pierre Cathedral of Angoulême and taught François reading and writing and instilled in him hatred of the Huguenots.

François worked eleven years as a valet and clerk of the Maître du Port des Rosiers, a lawyer of the court of justice for Angoulême. He then became a courier for the Angoulême prosecutor. Because Angoulême fell under the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Paris, François was frequently in the city. Around 1602, he moved to Paris where he served as the correspondent for the Angoulême prosecutor for four years.

François became obsessed with religion. In 1606, he entered the strict Order of the Feuillants as a lay brother but was dismissed after a short period because of his unusual mystical visions. He then applied to the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) but his application was rejected. To make ends meet, François became a school teacher, teaching catechism (religious instruction).

In 1609, François claimed to have had a vision instructing him to convince King Henri IV to convert the Huguenots to Catholicism. Between the spring of 1609 and the spring of 1610, François made three unsuccessful three trips to Paris to tell King Henri IV of his vision.

François then interpreted Henri IV’s decision to intervene militarily in the War of the Jülich Succession on the side of the Protestant forces against the Catholic Habsburg forces as the beginning of a war against the Pope. To François, this was an act against God and so he decided to kill King Henri IV of France.

********************

The Assassination

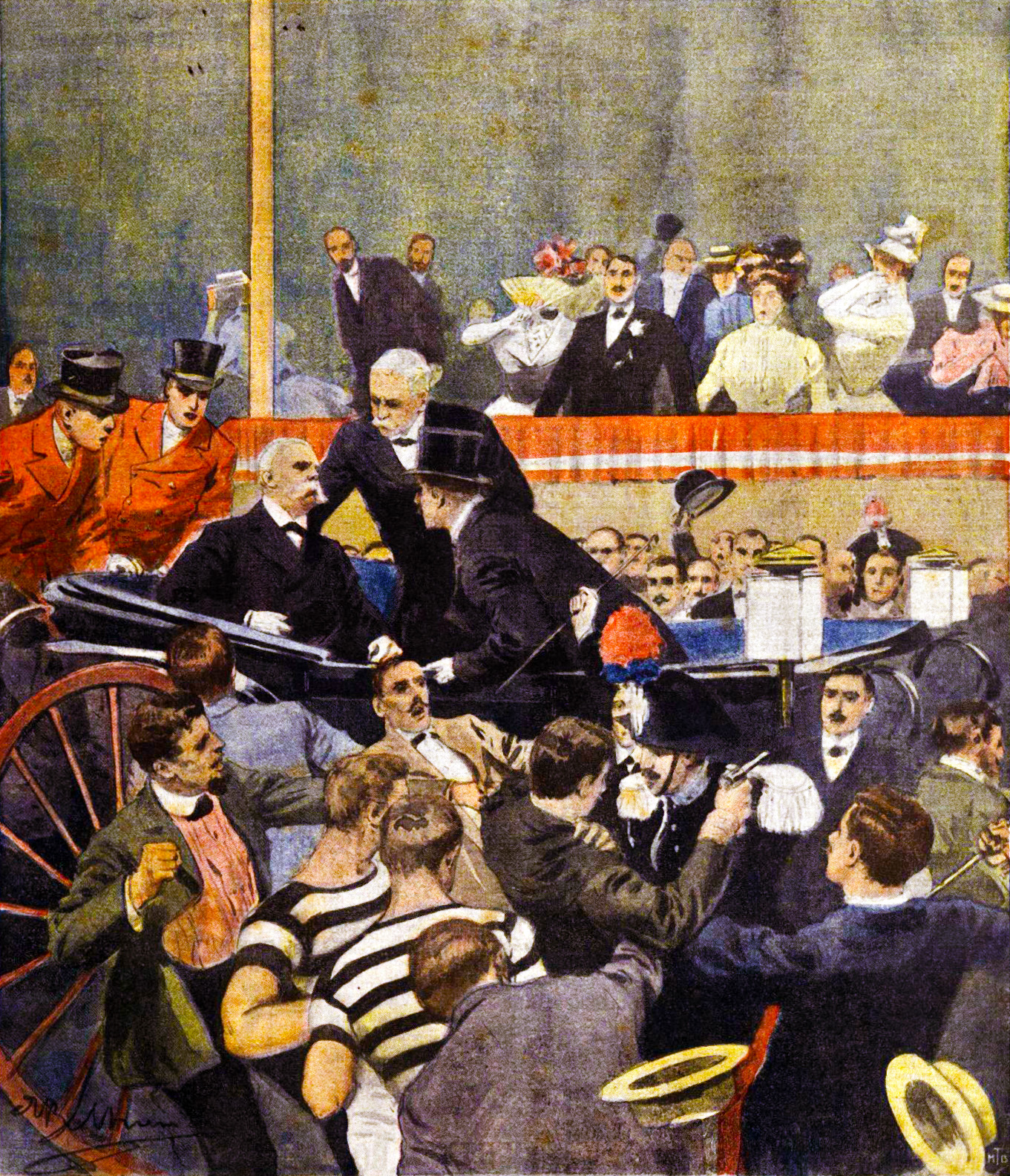

The assassination of Henri IV and arrest of Ravaillac on May 14, 1610, oil on canvas by Charles-Gustave Housez (1860); Credit – Wikipedia

The coronation of Henri’s second wife Marie de’ Medici was planned after their marriage in 1600 but it was postponed for financial reasons. Because of his imminent departure to fight in the War of the Jülich Succession, Henri decided to have a coronation for his wife to give her greater legitimacy in case it became necessary for her to be regent in his absence. The coronation of Queen Marie took place on May 13, 1610, at the Basilica of Saint-Denis near Paris. After the coronation, Henri returned to the Louvre Palace in Paris to find the doctor and astrologer of his cousin Charles de Bourbon, Count of Soissons waiting to warn him about the next day. Henri refused to see him. He had a busy next few days. On May 14, Henri planned to work on the last details of his military expedition. He planned to relax and go hunting on May 15. Queen Marie’s solemn entry into Paris after her coronation was planned for May 16 and on May 17, Henri planned to join his army as they began to fight in the War of the Jülich Succession.

In the late afternoon of May 14, 1610, Henri IV left the Louvre Palace to meet with Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully, one of his closest advisers, who was ill at his home. Since Sully’s home was nearby, Henri decided it was unnecessary to be escorted by the Horse Guard. Instead, the king was accompanied by an escort of a few soldiers. Riding in the carriage with Henri were Jean-Louis de Nogaret, Duke of Épernon and Hercule de Rohan, Duke of Montbazon.

François Ravaillac had stolen a knife from an inn and followed Henri’s carriage as it left the Louvre Palace. François caught up with Henri’s carriage in the Rue de la Ferronnerie, a narrow street in today’s Les Halles district, not far from the Louvre. A hay cart and a cart loaded with barrels of wine had difficulty moving and caused congestion. Henri lifted up the leather curtain of his carriage to see what was causing the delay. The footmen standing on Henri’s carriage’s step moved away to disperse the crowd that had recognized the king.

François took advantage of the situation and rushed at the carriage, stabbing three times. The first blow hit Henri’s armpit and did not cause much damage. However, the second blow was fatal, cutting Henri’s vena cava and aorta, the main blood vessels in and out of the heart. The last blow cut the Duke of Montbazon’s sleeve. Henri’s carriage raced back to the Louvre Palace where he soon died. Henri’s death left his wife Queen Marie with six children, aged one to eight. Henri was succeeded by his eldest son, the eight-year-old King Louis XII, with Queen Marie serving as Regent.

The commemorative plaque embedded in the pavement of the Rue de la Ferronnerie in Paris, marking the site of the assassination of Henri IV; Credit – Wikipedia

********************

What happened to François Ravaillac?

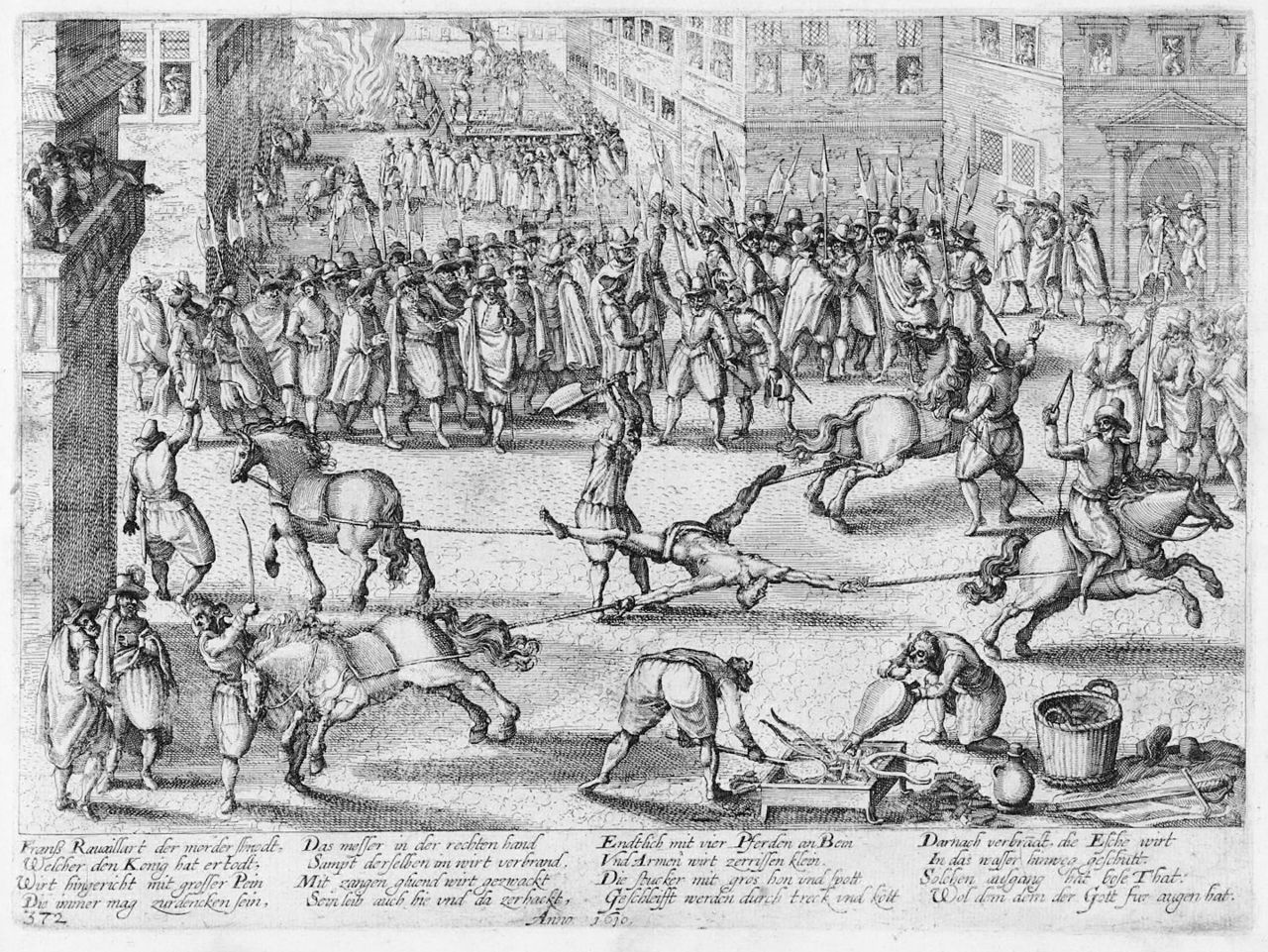

The execution of François Ravaillac; Credit – Wikipedia

Having done what he set out to do, François Ravaillac did not flee. The Duke of Épernon intervened to prevent François from being lynched by the crowd. François was brought to the Hôtel de Retz where he stayed for two days. The next day he was taken to the Hotel du Duc d’Épernon before being taken into custody at the Conciergerie prison.

François was tortured to make him identify accomplices but he denied that he had any and insisted that he acted alone. He said to his interrogators, “I know very well he is dead; I saw the blood on my knife and the place where I hit him. But I have no regrets at all about dying because I’ve done what I came to do.” At the end of a ten-day trial by the Parliament of Paris, it was determined that the assassination of King Henri IV was the isolated act of a Catholic fanatic and François Ravaillac was sentenced to death.

On May 27, 1610, François Ravaillac was brought from the Conciergerie the short distance to the square in front of the Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral where he did his penance with bare feet, in his shirt, holding a candle in his hand. François then climbed into a garbage cart which took him to the Place de Grève (the current Place de l’Hotel-de-Ville) where on a small scaffold the tortures of the executioner Jean Guillaume and his assistants lasted for hours.

François Ravaillac’s right hand, which held the knife that had killed King Henri IV, was burned off with sulfur fire. Molten lead, boiling oil, pitch, hot resin, wax, and sulfur were melted and poured over his body. A horse was attached to each of his arms and legs. When the horses pulled, his body was dismembered. The remains of his body were thrown into the fire, reduced to ashes, and thrown to the wind.

********************

The Funeral and Burial of King Henri IV of France

King Henri IV laying in state in the State Bedchamber in the Louvre Palace, engraving after François Quesnel; Credit – Wikipedia

King Henri IV’s remains were autopsied on May 15, 1610. His heart was placed in a silver urn, and in keeping with a promise made some years earlier, it was entombed at the Church of Saint Louis of La Flèche in the province of Maine, France. The funeral ceremonies were elaborate and lasted until the burial on July 1, 1510. Henri’s body was embalmed and then placed on a bier in the Chambre de Parade du Roi (State Bedchamber) in the Louvre Palace. One hundred low masses and six high masses were said there each day.

On June 10, 1610, Henri’s casket was taken to the Salle des Caryatides (Cariatides Room) in the Louvre Palace. An effigy was constructed out of wicker with a wax face molded from the face of the king, wearing coronation dress and the royal crown. Twice a day, servants pretended to serve him a meal, a traditional ritual symbolizing the continuity of the royal dignity beyond the death of the King.

The effigy was removed on June 21, 1510. Funeral orations were heard in all the parishes of the kingdom, followed by a week of tributes to King Henri IV by the various government officials including a blessing from eight-year-old King Louis XIII. On June 29, 1510, Henri’s casket was taken to Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral where several ceremonies were held, including the funeral mass on June 30, 1510.

After the funeral, Henri’s casket was brought to the traditional burial site of the French royal family, the Basilica of Saint-Denis in Saint-Denis, now a northern suburb of Paris. The casket was placed in a chapel with the effigy awaiting burial the next day. Henri’s tomb was destroyed during the French Revolution but there is a memorial to him at the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

Memorial to Henri IV at the Basilica of Saint-Denis; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

********************

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). François Ravaillac. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Ravaillac [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Henry IV of France. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_IV_of_France [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). Assassinat d’Henri IV. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assassinat_d%27Henri_IV [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). François Ravaillac. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Ravaillac [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2020). Henri IV (roi de France). [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_IV_(roi_de_France) [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].

- Mehl, Scott. (2016). King Henri IV of France. [online] Unofficial Royalty. Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/king-henri-iv-of-france/ [Accessed 25 Feb. 2020].