by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

The last Grand Duchess of Russia and the youngest of the six children of Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia and Dagmar of Denmark (Empress Maria Feodorovna), Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia was born at Peterhof Palace on June 13, 1882.

Olga’s mother was the daughter of King Christian IX of Denmark and among Olga’s maternal first cousins were King Constantine I of Greece, King George V of the United Kingdom, King Christian X of Denmark, and King Haakon VII of Norway.

Olga had five older siblings:

- Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia (1868 – 1918), married Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (Alexandra Feodorovna), had five children

- Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (1869 – 1870), died young of meningitis

- Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871 – 1899), unmarried, died of tuberculosis

- Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875 – 1960), married Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia, had seven children

- Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1878 – 1918), married morganatically Natalia Sergeyevna Sheremetyevskaya, later Countess Brasova, had one child

Seated (L to R): Alexander III with Olga, George; standing (L to R): Michael, Maria Feodorovna, Nicholas, and Xenia; Credit – Wikipedia

In 1881, the year before Olga was born, her paternal grandfather Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia was assassinated when a bomb was thrown at his carriage as he rode through St. Petersburg, and Olga’s father became Emperor. Concerned about the security of his family, Alexander III moved his family from the Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg to Gatchina Palace located 28 miles (45 km) south of St. Petersburg. Gatchina Palace became the family’s prime residence.

Olga as a young girl, Credit – Wikipedia

Like her other siblings, Olga was raised in a relatively simple manner considering her status. She slept in a cot, woke up at 6:00 AM, took cold baths, ate simple, plain meals, and her rooms were furnished with simple furniture. The Imperial children had a large extended family and often visited the families of their British, Danish, and Greek cousins.

Emperor Alexander III and Empress Maria Feodorovna believed that their children should spend their spare time in a useful manner and so they learned cooking, woodworking, and how to make puppets for their puppet theater. Alexander III believed that his children should learn about the outdoors, and so they were taught to ride and they gardened and kept animals that they had to look after themselves. Olga’s brother Michael, who was four years older, was her childhood companion and the two would always remain close. They were educated together and played together.

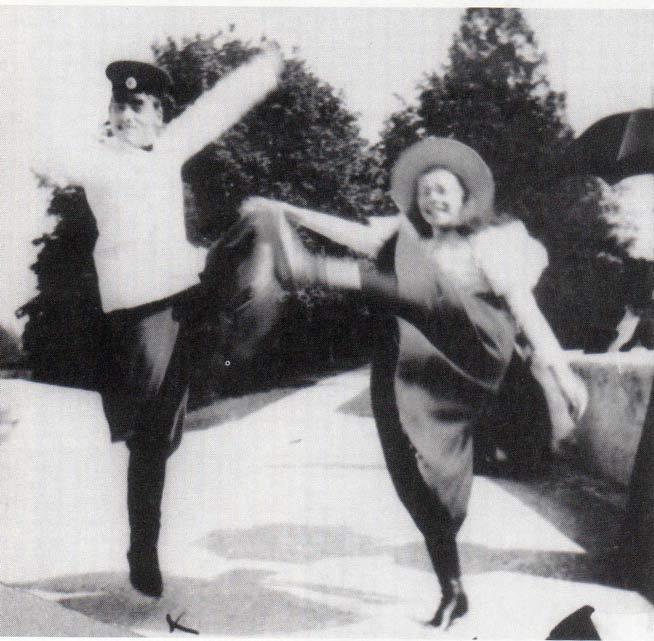

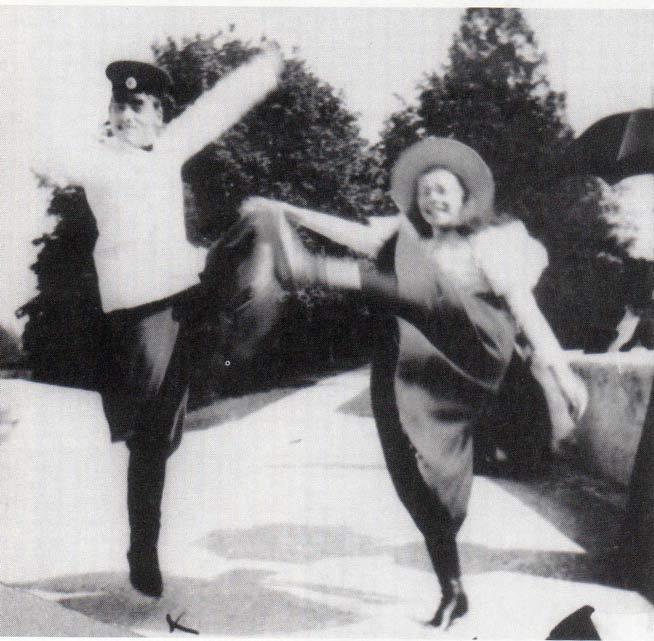

Michael and Olga; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In 1894, Olga’s father Alexander III unexpectedly died at the age of 49 and her brother Nicholas became Emperor. After her father’s death, Olga’s mother moved back to Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg with Michael and Olga. Olga’s debut into society was delayed due to the death of her brother George in 1899. After her debut, Olga was escorted to society events by Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg.

Olga with her first husband Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg; Credit – Wikipedia

Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg, a second cousin, was fourteen years older than Olga. He was the only child of Duke Alexander Petrovich of Oldenburg and Eugénie Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg. Peter’s mother was a granddaughter of Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia through Nicholas I’s daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolayevna, and his father was a great-grandson of Paul I, Emperor of All Russia through his paternal grandmother Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna.

It seems that Olga’s mother and Peter’s mother, who were good friends, had arranged a marriage between their two children so that Olga would not have to marry a foreign prince and could always be on call for her mother. Olga told her official biographer, Ian Vorres, “I was just tricked into it.” Olga was brought into a room where Peter stammered through a proposal. Their engagement, announced in May 1901, was unexpected by family and friends, as Peter had shown no prior interest in women and it was assumed he was homosexual. The wedding quickly followed on August 9, 1901. Olga told Vorres, “I shared his roof for fifteen years and never once were we husband and wife.” Obviously, there were no children. Olga and Peter lived in a 200-room mansion in St. Petersburg and their bedrooms were at opposite ends of the building. Peter was always kind and considerate towards her but Olga longed for love, a normal marriage, and children.

Olga and Peter; Credit – Wikipedia

In April 1903, Olga attended a military review of the Blue Cuirassier Guards. Her brother Michael was one of the commanders. There she saw a tall, handsome man in the uniform of the Blue Cuirassier Guards, and their eyes met. Olga said to Vorres, “It was fate. It was also a shock. I suppose I learned on that day that love at first sight does exist.” Michael arranged for Nikolai Alexandrovich Kulikovsky and Olga to meet. A few days later Olga asked Peter for a divorce. He refused, saying that he would reconsider his decision after seven years.

Nikolai was promoted to captain of the Blue Cuirassier Guards and sent far away to the provinces. Olga and Nikolai regularly corresponded. In 1906, Olga’s husband Peter appointed Nikolai as one of his aides-de-camp. Nikolai was told that his quarters would be in the Oldenburg mansion in St. Petersburg. The living arrangements at the mansion were a well-kept secret and continued until the start of World War I when Olga went to be a nurse at the front and Nikolai went to war with his regiment. Peter did not keep his promise to reconsider a divorce after seven years.

Over the years, Olga had continued to ask her brother Nicholas II for permission to marry Nikolai. Nicholas II always refused because he believed that marriage was for life and that the royalty should only marry royalty. In 1912, when Olga’s brother Michael married a commoner without permission, Nicholas banished him from Russia. Fearing for Nikolai’s safety in the war, Olga pleaded with her brother Nicholas II to transfer him to the relative safety of Kyiv, where she was stationed at a hospital. In 1916, after visiting Olga in Kyiv, Nicholas had a change of heart and he officially annulled her marriage to Peter. On November 16, 1916, Olga and Nikolai were married at the Kievo-Vasilievskaya Church in Kiev. Olga’s mother Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, her sister’s husband Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (Sandro), two fellow nurses from the hospital in Kyiv, and four officers of Nikolai’s regiment attended.

Olga and Nikolai Kulikovsky on their wedding day; Credit – Wikipedia

Olga and Nikolai had two sons:

- Tikhon Nikolaevich Kulikovsky (1917 – 1993), married (1) Agnet Petersen, no children, divorced (2) Libya Sebastian, had one daughter, divorced (3) Olga Nikolaevna Pupynina, no children

- Guri Nikolaevich Kulikovsky (1919 – 1984), married Ruth Schwartz, had three children, divorced (2) Aze Gagarin, no children

Guri, Olga, Tikhon and, Nikolai, circa 1920; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

The February Revolution was the first of two revolutions that occurred in Russia in 1917. The February Revolution was caused by military defeats during World War I, economic issues, and scandals surrounding the monarchy. The immediate result was the abdication of Olga’s brother Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire. Later in 1917, the October Revolution occurred, paving the way for the establishment of the Soviet Union.

After Nicholas II abdicated, many members of the Romanov family, including Nicholas, his wife, and their children, were placed under house arrest. In search of safety, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (Sandro), and Grand Duchess Olga traveled to the Crimea where they were joined by Olga’s sister (Sandro’s wife) Grand Duchess Xenia. They lived at Sandro’s estate, Ai-Todor, where they were placed under house arrest by the local Bolshevik forces. On August 12, 1917, Olga’s first child Tikhon Nikolaevich was born during their house arrest.

The Romanovs under house arrest at Ai-Todor in the Crimea in 1918. Standing: Colonel Nikolai Kulikovsky (Grand Duchess Olga’s husband), Mr. Fogel, Olga Konstantinovna Vasiljeva, Prince Andrei (Xenia’s son). Seated: Mr. Orbeliani, Prince Nikita (Xenia’s son), Grand Duchess Olga (Xenia’s sister), Grand Duchess Xenia, Empress Maria Feodorovna (Xenia’s mother), Grand Duke Alexander (Xenia’s husband). On the floor: Prince Vasili (Xenia’s son), Prince Rostislav (Xenia’s son), and Prince Dmitri (Xenia’s son); Credit – Wikipedia

Other Romanovs also gathered at their palaces in Crimea. There they witnessed the October Revolution later that year, and then in 1918 came the news of the murder of Nicholas II and his family and their servants. Olga’s younger brother Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich had been murdered along with his secretary the month before Nicholas’ murder. Being in Crimea became precarious due to food shortages, visits to the home by the Bolshevik officials, and the threat of being murdered by the Bolsheviks. On April 11, 1919, Empress Maria Feodorovna, her daughter Xenia, Xenia’s five youngest sons along with Xenia’s daughter Irina and her husband Prince Felix Yusupov left Russia forever aboard the British battleship HMS Marlborough.

Olga and Nikolai refused to leave Russia. One of Empress Maria Feodorovna’s personal bodyguards, Timofei Ksenofontovich Yatchik took Olga, Nikolai, and their son Tikhon to his hometown Novominskaya where Olga gave birth to her second child Guri Nikolaevich in a rented farmhouse on April 23, 1919. As the White Army was pushed back and the Red Army approached, the family set out on their last journey through Russia. Yatchik, the former bodyguard, accompanied Olga and her family as they traveled to Rostov-on-Don and then to Novorossiysk where the Danish consul Thomas Schytte gave them refuge in his home. Finally, they arrived in Copenhagen, Denmark on April 2, 1920, and Olga was reunited with her mother. Yatchik, the former imperial bodyguard, guarded Empress Maria Feodorovna until she died in 1928, and then lived the rest of his life in Denmark.

Timofei Ksenofontovich Yatchik who assisted Olga and her family in leaving Russia; Credit – Wikipedia

Olga and her family lived with her mother in Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen, Denmark where her first cousin King Christian X of Denmark was quite inhospitable. Eventually, they moved to Hvidøre, the country house Empress Maria Feodorovna and her sister Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom had purchased together in 1906. Nikolai and Marie Feodorovna did not get along. He was resentful of Olga acting as her mother’s secretary and companion and Marie Feodorovna was distant toward him.

After Maria Feodorovna’s death, Hvidøre was sold and with Olga’s portion of the proceeds, Olga and Nikolai were able to purchase Knudsminde Farm, outside of Copenhagen. The farm became a center for the Russian monarchist and anti-Bolshevik community in Denmark. Olga lived a simple life working in the fields, doing household chores, and painting. She painted throughout her life and her usual subject was scenery and landscape, but she also painted portraits and still life.

Flowers by Olga Alexandrovna; Credit – Wikipedia

After World War II, the Soviet Union notified the Danish government that Olga was accused of conspiracy against the Soviet government. Because she was fearful of an assassination or kidnap attempt, Olga decided to move her family across the Atlantic to the relative safety of rural Canada. On June 2, 1948, Olga, Nikolai, Tikhon, and his Danish-born wife Agnete, Guri, and his Danish-born wife Ruth along with their two children and Olga’s devoted companion and former maid Emilia Tenso (Mimka) started their voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The family lived in Toronto, Canada until they purchased a 200-acre farm in Halton County, Ontario, Canada near Campbellville. By 1952, Olga and Nikolai’s sons had moved away and the farm became a burden so they sold it and moved to a five-room house at 2130 Camilla Road, Cooksville, Ontario, Canada, a suburb of Toronto.

Nikolai died on August 11, 1958, aged 76. After her husband’s death, Olga became increasingly infirm. Unable to care for herself, Olga stayed in the Toronto apartment of Russian émigré friends, Konstantin and Sinaida Martemianoff. Olga’s sister Xenia died in April 1960. On November 21, 1960, Olga slipped into a coma and the last Grand Duchess of Russia died November 24, 1960, at the age of 78. Olga was buried next to her husband Nikolai at York Cemetery in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Grave of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and Nikolai Kulikovsky; Photo Credit – By Alex.ptv – Self-photographed, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38411347

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_Peter_Alexandrovich_of_Oldenburg [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Duchess_Olga_Alexandrovna_of_Russia [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Nikolai Kulikovsky. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolai_Kulikovsky [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Куликовский, Николай Александрович. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9,_%D0%9D%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B9_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87 [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Ольденбургский, Пётр Александрович. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9E%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B3%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9,_%D0%9F%D1%91%D1%82%D1%80_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87 [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- Ru.wikipedia.org. (2018). Ольга Александровна. [online] Available at: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9E%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%B3%D0%B0_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BD%D0%B0 [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

- Vorres, I. (2018). The Last Grand Duchess. Toronto: Key Porter Books Limited.