by Susan Flantzer © Unofficial Royalty 2018

Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia in 1916; Credit – Wikipedia

They were known collectively as OTMA – the group nickname they made up for themselves from the first letter of each sister’s name in the order of their births. Five and a half years apart from the oldest to the youngest, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia were the four eldest of the five children of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia and Alix of Hesse and by Rhine (Empress Alexandra Feodorovna). Their younger brother Alexei was the heir to the Russian throne. The five children were great-grandchildren of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. Their mother was the daughter of Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Alice of the United Kingdom. It was through the descent from Queen Victoria that hemophilia came into the Russian Imperial Family. Alexei inherited hemophilia through his mother and we know from the DNA analysis of the family’s remains, that Anastasia was also a carrier.

The four sisters shared the same patronymic – Nikolaevna – their second name derived from the father’s first name Nicholas, meaning daughter of Nicholas. They shared the same title – Velikaia Knazhna (in Russian: Великая Княжна) meaning Grand Princess, commonly translated into English as Grand Duchess. It was the title of daughters and male-line granddaughters of Emperors of Russia and wives of Grand Dukes of Russia.

The four sisters had a close relationship – they grew up together, shared experiences together, and died together – so this article will be a collective biography, after some information about each sister.

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna of Russia

Olga in 1914; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Olga was a big baby, 10 pounds/4.5 kg, and caused her mother some trouble during delivery. She was born on November 15, 1895, at Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, located just south of St. Petersburg, Russia, where Alexander Palace and the larger Catherine Palace, the two summer palaces, are located. Olga was christened eleven days after her birth, on her parents’ first wedding anniversary, at the church in the Catherine Palace, with her paternal grandmother Empress Maria Feodorovna (born Princess Dagmar of Denmark) and her paternal great-uncle Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich as her godparents.

In September 1896, Olga traveled with her parents to Balmoral Castle in Scotland to visit her great-grandmother Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom.

Seated: Empress Alexandra Feodorova, Olga on her lap, Queen Victoria; Standing: Emperor Nicholas II, The Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII); Photo Credit – by Robert Milne, bromide print on card mount, September 1896 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Olga was the closest with her sister Tatiana, born in 1897. The two sisters were dressed alike, shared a room, and were known as “The Big Pair.” Olga was kind and sympathetic. She felt deeply about people’s misfortunes and always tried to help. Olga liked to read more than her sisters and also wrote poetry. Pierre Gilliard, the French tutor of Olga and her sisters, noted that Olga learned her lessons better and faster than her sisters but she could become lazy when things were too easy. Her mother’s friend Anna Vyrubova recalled that Olga had a hot temper and struggled to keep it under control.

Because Olga reached her teens before World War I, there was talk about a marriage for her. The most serious talk was about a marriage between Olga and Prince Carol of Romania (the future King Carol II), the son of King Ferdinand I of Romania and Queen Marie, born a British princess and a first cousin of Olga’s mother. During a visit in 1914 to Romania, Olga did not like Carol, while Carol’s mother Queen Marie was unimpressed with Olga. Edward, Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VIII) and Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia (the future King Alexander I of Yugoslavia) were also mentioned as potential husbands. Olga wanted to marry a Russian and remain in her own country. When World War I started, any marriage talk was postponed.

Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna of Russia

Tatiana in 1914; Credit – Wikipedia

Tatiana was born June 10, 1897, at Peterhof Palace near St. Petersburg. Like her older sister Olga, she was named after a character in Alexander Pushkin’s classic Russian novel Eugene Onegin. Tatiana was christened on June 20, 1897, at the Peterhof Palace church. Her godparents were her paternal grandmother Empress Maria Feodorovna (born Princess Dagmar of Denmark), her great-great-uncle and a son of Nicholas I, Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich, and her paternal aunt Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna

Footman Alexei Trupp (who was killed with the family) and Tatiana, 1902; Credit – Wikipedia

Tatiana, like her sister Olga, was a good student but worked harder and was more dedicated. She had a great talent for sewing, embroidery, and crocheting. Tatiana was practical, had a natural talent for leadership, and so she was nicknamed “The Governess” by her sisters. She was closer to her mother than any of her sisters and was considered by many to be Empress Alexandra’s favorite daughter. Therefore, Tatiana was the one sent as the sisters’ representative when they wanted something from their parents.

Empress Alexandra with her daughters, circa 1908; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In 1914, Tatiana, while nursing in a hospital, met an injured army officer, Dmitri Yakovlevich Malama, who was later appointed an equerry to the court at Tsarskoye Selo. A romance developed between the two and Malama presented Tatiana with a French bulldog named Ortipo. When the dog died, Malama gave Tatiana another dog which was taken into captivity and was killed along with the family. Apparently, Tatiana’s mother approved of Malama. She wrote in a letter to her husband Nicholas II about Malama: “I must admit that he would be an excellent son-in-law – why are foreign princes different from him?” World War I stopped any further development of the relationship. After the Bolsheviks came to power, Malama joined the White Army and was killed in 1919 in Ukraine while commanding a unit of the White Army in the civil war against the Bolsheviks.

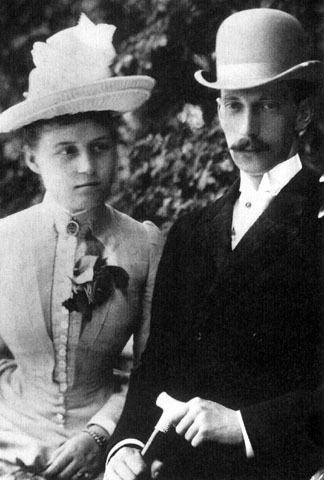

Tatiana Nikolaevna wearing a Red Cross nursing uniform and Dmitri Yakovlevich Malama; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In January 1914, the Serbian Prime Minister delivered a letter from King Peter I of Serbia to Nicholas II, in which King Peter expressed his desire for his son Alexander to marry Tatiana. This is the same Alexander (see above) who was also mentioned as a possible husband for Olga. Nicholas II invited Peter I and his son Alexander to Russia where Tatiana and Alexander met. However, the marriage negotiations ended with the outbreak of World War I. Tatiana and Alexander wrote letters to each other until her death. When Alexander learned about the murder of Tatiana, he was extremely distraught.

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna of Russia

Maria in 1914; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Maria was born at Peterhof Palace near St. Petersburg on June 26, 1899. The pregnancy had been difficult for Empress Alexandra and she spent the last months in a wheelchair. During the birth, there were fears for the lives of both the mother and the baby. Maria was christened at the church in Peterhof Palace on July 10, 1899, with a large group of godparents: her paternal grandmother Empress Maria Feodorovna, her paternal uncle Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, her paternal second cousin once removed Prince George of Greece (son of King George I of Greece and Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia), her maternal aunt Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna (born Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine, wife of Nicholas II’ uncle Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich), her great-great-aunt by marriage Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna (born Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg, wife of Grand Duke Konstantine Nikolaevich), and her maternal great-uncle Prince Heinrich of Hesse and by Rhine.

Maria and Anastasia aboard the Imperial yacht Standart, circa 1911; Credit – Wikipedia

Maria was closest to her younger sister Anastasia and the two sisters were called “The Little Pair.” The two younger sisters shared a room, often wore variations of the same dress, and spent much of their time together. Anastasia was enthusiastic and energetic and often dominated Maria who felt she had to apologize for Anastasia’s antics. Her sisters often took advantage of her kindheartedness. As more or less, the middle child, Maria sometimes felt insecure and left out by her older sisters and feared she was not loved as much as the other children.

Maria in the schoolroom in 1909; Credit – Wikipedia

Taking after her paternal grandfather Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia, Maria was strong and broad-boned and had problems with being overweight which worried her mother. The sisters’ English teacher Charles Sydney Gibbes remarked that Maria was surprisingly strong, and sometimes, for the sake of joking, she easily lifted him from the floor. Maria was not interested in schoolwork but had a talent for drawing and sketching.

Maria enjoyed flirting with the young soldiers she encountered at the palace and on family holidays. She particularly loved children and said she would love nothing more than to marry a Russian soldier and have twenty children. When an engagement between Olga and Crown Prince Carol of Romania did not materialize, Carol asked for Maria’s hand but her parents refused because they considered Maria too young.

Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg, a maternal uncle of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh) was a son of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna’s eldest sister Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine. In his childhood, Lord Mountbatten was close to his aunt Alexandra’s children, his first cousins. At a very young age, he began a “lifelong love affair” with Maria and kept a framed photo of her by his bed until he, like his Romanov first cousins, was also violently murdered. He wrote about Maria: “I was mad about her, and determined to marry her. You could not imagine anyone more beautiful than she was!”

Lord Mountbatten kept this photo of Maria from 1914 (on the left) by his bed, until his own violent death in 1979 when he was murdered by the Irish Republican Army in a bomb explosion.

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia

Anastasia in 1918; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Anastasia was born on June 18, 1901, at Peterhof Palace near St. Petersburg. She was named in honor of Princess Anastasia of Montenegro, a close friend of Anastasia’s mother, who married twice, both times to two grandsons of Nicholas I, Emperor of All Russia. There was, once again, disappointment that Empress Alexandra had not given birth to a boy. In 1797, Paul I, Emperor of All Russia proclaimed a new succession law that stated that the eldest son of the emperor shall inherit the throne followed by other dynasts according to primogeniture in the male line. The throne could only pass to a female and through the female-line upon the extinction of all legitimately-born male dynasts.

Photograph taken on the occasion of Anastasia’s christening; Empress Alexandra is dressed in mourning due to the death of her grandmother Queen Victoria earlier in the year; Credit – Wikipedia

The energetic and fearless Anastasia liked to play tricks, had a great acting talent, and enjoyed mimicking other people. “She undoubtedly held the record for punishable deeds in her family, for in naughtiness she was a true genius”, said Gleb Botkin, son of the court physician Yevgeny Botkin, who died with the family at Yekaterinburg.

Maria and Anastasia making faces for the camera, circa 1915; Credit – Wikipedia

Anastasia received an education from tutors and studied French, English, German, history, geography, religion, science, grammar, mathematics, drawing, dancing, and music. While she was intelligent, Anastasia did not like the strict structure of her education. Her English teacher Charles Sydney Gibbes recalled that Anastasia once tried to bribe him to raise her grade with a bouquet of flowers. After he refused, she attempted to do the same thing with her Russian teacher.

Anastasia with her brother Alexei in 1909; Credit – Wikipedia

Anastasia had a close relationship with her younger brother Alexei. If he did not feel well because of his hemophilia, Anastasia was the one who was able to distract him from his pain and cheer him up.

Family Life

Russian Imperial family (circa 1913-1914); Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Nicholas, Alexandra, and their five children lived mostly at Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, a short distance from St. Petersburg, where they occupied only a part of the several dozen rooms. Sometimes they moved to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, even though it was very large and very cold, and Tatiana and Anastasia were often sick there. The children spoke English with their mother, Russian with their father, German with their mother’s relatives, and also learned French.

Nicholas II with his daughters Tatiana, Maria, Olga, and Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia aboard the Imperial yacht Standart in 1914; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

In the middle of June, the family went on trips on the Imperial yacht Standart, usually sailing through the Finnish skerries, small rocky islands, too small for human habitation. During the summer, the family would spend some time at Livadia Palace in the Crimea on the Black Sea. There the family bathed in the warm sea, built sandcastles, and sometimes went into the city to ride or walk through the streets and visit shops. They could never have such freedom in St. Petersburg where their appearance would create a big commotion.

Anastasia, Olga, Alexei, lady-in-waiting Margarita Sergeevna Khitrovo and Maria on the beach of the Black Sea in 1916; Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Family life was intentionally not as luxurious as we would imagine. Nicholas and Alexandra were afraid that wealth would spoil their children’s character. The four sisters got up at eight in the morning and took a cold bath. The two elder sisters shared a room as did the two younger sisters. The sisters slept on folding army cots, labeled by the owner’s name, under thick blue blankets decorated with the owner’s monogram. The tradition of sleeping on folding army cots was started by Catherine the Great for her grandsons. The army cots could easily be moved closer to the heat in winter, closer to open windows in the summer, next to the Christmas tree, or in the brother’s room. The walls of their rooms were decorated with icons and photographs.

Last Years

Maria, Olga, Anastasia, and Tatiana in captivity at Tsarskoe Selo in the spring of 1917; Credit – Wikipedia

Having had four daughters, Empress Alexandra felt great pressure to provide an heir. Finally, in 1904, she gave birth to a son, Alexei. However, it would soon become apparent that she was a carrier of hemophilia, and her young son was a sufferer. This would cause great pain to Alexandra, and great measures were taken to protect him from harm and to hide the illness from the Russian people. When it eventually became public knowledge, it led to more dislike for Alexandra, with many Russian people blaming her for the heir’s illness. See Unofficial Royalty: Hemophilia in Queen Victoria’s Descendants.

After working with many physicians to help Alexei, Empress Alexandra turned to mystics and faith healers. This led to her close, and disastrous, relationship with Grigori Rasputin. Several times he appeared to have brought Alexei back from the brink of death, further cementing Alexandra’s reliance. There were many rumors about Rasputin’s relationship with Alexandra and her children. Rasputin’s friendship with the children was evident in some of the messages he sent to them. While Rasputin’s visits to the children were, by all accounts, completely innocent, the family was scandalized. To many historians and experts, the Imperial Family’s relationship with Rasputin would contribute greatly to the fall of the Russian monarchy. For more information see Unofficial Royalty: Murder of Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin.

Empress Alexandra with Rasputin, her children, and governess Maria Vishnyakova; Credit – Wikipedia

The reign of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia would see the first Russian Constitution in 1906 which established a parliament of sorts, however, his reign also saw a steady decline in his popularity and support. Nicholas’ decision to fully mobilize the Russian troops in 1914 led to Russia’s entry into World War I. By 1917, his authority had diminished, and on March 15, 1917, he was forced from the throne. Nicholas formally abdicated for himself and his son, making his younger brother Michael the new Emperor. However, Michael refused to accept until the Russian people could decide on continuing the monarchy or establishing a republic. This never happened.

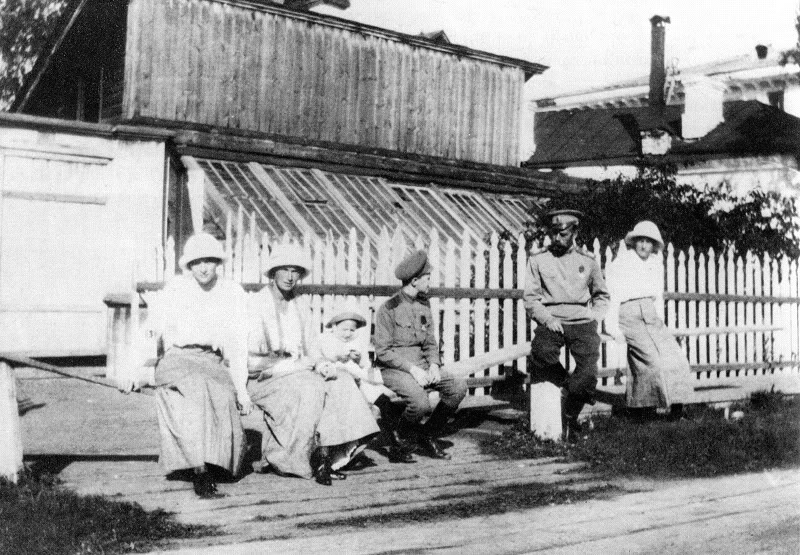

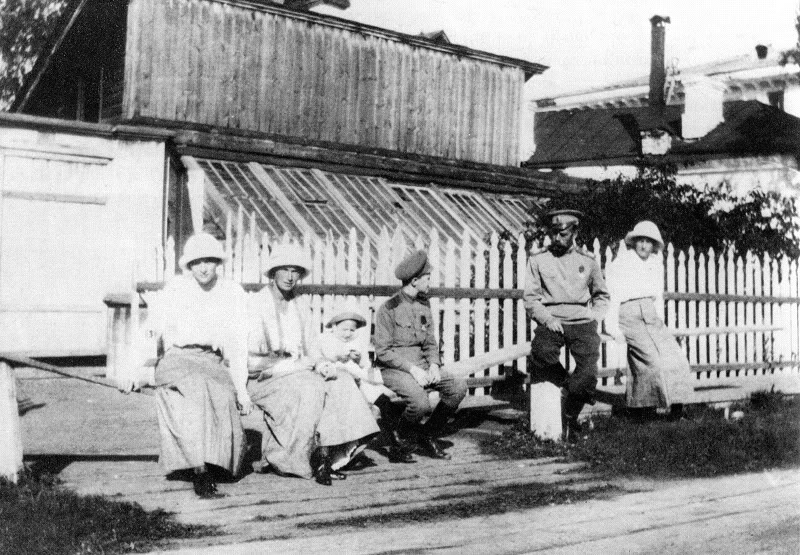

Nicholas and his children sit in front of a fence and a greenhouse during their captivity in Tobolsk: (l-r) Tatiana, Olga, son of a servant, Alexei, Nicholas, and Anastasia; Credit – Wikipedia

Nicholas returned to the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo where he and his family were held in protective custody. A few months later, in August, the family was moved to the city of Tobolsk, where they lived in the Governor’s Mansion under heavy guard. Their final move, in April 1918, was to Yekaterinburg where they were housed in the Ipatiev House, known as the “house of special purpose.” It was here, in the early hours of July 17, 1918, that Nicholas, Alexandra, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, Alexei, the family doctor Dr. Yevgeny Botkin, the maid Anna Demidova, the cook Ivan Kharitonov, and the footman Alexei Trupp were killed by the Bolsheviks who had come to power during the Russian Revolution. Their bodies were initially thrown down a mine, but fearing discovery, they were mutilated and hastily buried beneath some tracks. For more information, see

Discovery of Remains and Burial

In 1934, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of the Ipatiev House, produced an account of the execution and disposal of the bodies. His account later matched the remains of nine bodies found north of Yekaterinburg in 1991. In 1994, when the bodies of the Romanovs were exhumed, two were missing – one daughter, either Maria or Anastasia, and Alexei. The remains of the nine bodies recovered were confirmed as those of the three servants, Dr. Botkin, Nicholas, Alexandra, and three of their daughters. The remains of Olga and Tatiana were identified based on the expected skeletal structure of young women of their age. The remains of the third daughter were either Maria or Anastasia.

Icon of the Romanov Family in Nikolo-Tikhonov Monastery; Credit – Wikipedia

The family and their servants were canonized as new martyrs in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in 1981, and as passion bearers in the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000. Formal burial of Nicholas, Alexandra, Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia, Dr. Botkin, and the three servants took place on July 17, 1998, the 80th anniversary of their deaths, in the St. Catherine Chapel at the Peter and Paul Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. Boris Yeltsin, President of Russia, many Romanov family members, and family members of Dr. Botkin and the servants attended the ceremony. Prince Michael of Kent represented his first cousin Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. Three of his grandparents were first cousins of Nicholas II.

St. Catherine’s Chapel at the Peter and Paul Cathedral; Photo Credit – © Susan Flantzer

Until 2009, it was not entirely clear whether the remains of Maria or Anastasia were missing. On August 24, 2007, a Russian team of archaeologists announced that they had found the remains of Alexei and his missing sister in July 2007. In 2009, DNA and skeletal analysis identified the remains found in 2007 as Alexei and his sister Maria. In addition, it determined that the royal hemophilia was the rare, severe form of hemophilia, known as Hemophilia B or Christmas disease. The results showed that Alexei had Hemophilia B and that his mother Empress Alexandra and his sister Grand Duchess Anastasia were carriers of the disease. The remains of Alexei and Maria have not yet been buried. The Russian Orthodox Church has questioned whether the remains are authentic and blocked the burial.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited