by Scott Mehl © Unofficial Royalty 2017

Grand Duchy of Baden: In 1738, ten-year-old, Karl Friedrich succeeded as Margrave of Baden-Durlach upon his grandfather’s death. Baden-Durlach was one of the branches of the Margraviate of Baden, which had been divided several times over the previous 500 years. When August George, the last Margrave of Baden-Baden, died in 1771 without heirs, Karl Friedrich inherited the territory. This brought all of the Baden territories together once again, and Karl Friedrich became Margrave of Baden. Upon the end of the Holy Roman Empire, Karl Friedrich declared himself sovereign, as Grand Duke of the newly created Grand Duchy of Baden. Friedrich II, the last Grand Duke of Baden formally abdicated the throne of Baden on November 22, 1918. The land that encompassed the Grand Duchy of Baden is now located in the German state of Baden-Württemberg.

********************

Friedrich I, Grand Duke of Baden – source: Wikipedia

Friedrich I was born September 9, 1826, in Karlsruhe, Grand Duchy of Baden, now in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, the third son of Leopold, Grand Duke of Baden and Princess Sofia of Sweden. He had seven siblings:

- Princess Alexandrine (1820-1904) – married Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, no issue

- Prince Ludwig (born and died 1822) – died in infancy

- Ludwig II, Grand Duke of Baden (1824-1858) – unmarried

- Prince Wilhelm (1829-1897) – married Maria Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg, had issue

- Prince Karl (1832-1906) – married Rosalie von Beust, had issue

- Princess Marie (1834-1899) – married Ernst Leopold, 4th Prince of Leiningen, had issue

- Princess Cecilie (1839-1891) – married Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaevich of Russia, had issue

Portrait of Friedrich and Luise, 1856. source: Wikipedia

On September 20, 1856, Friedrich married Princess Luise of Prussia at the Neues Palais in Potsdam, Kingdom of Prussia, now in the German state of Brandenburg. Luise was the daughter of the future King Wilhelm I of Prussia and Princess Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. The marriage was encouraged by Luise’s uncle King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia who wanted to form an alliance with Baden to strengthen Prussia’s influence within the German Confederation against Austria. Friedrich and Luise had three children:

- Friedrich II, Grand Duke of Baden (1857-1928) – married Hilda of Nassau, no issue

- Princess Victoria (1862-1930) – married King Gustav V of Sweden, had issue

- Prince Ludwig (1865-1888) – unmarried

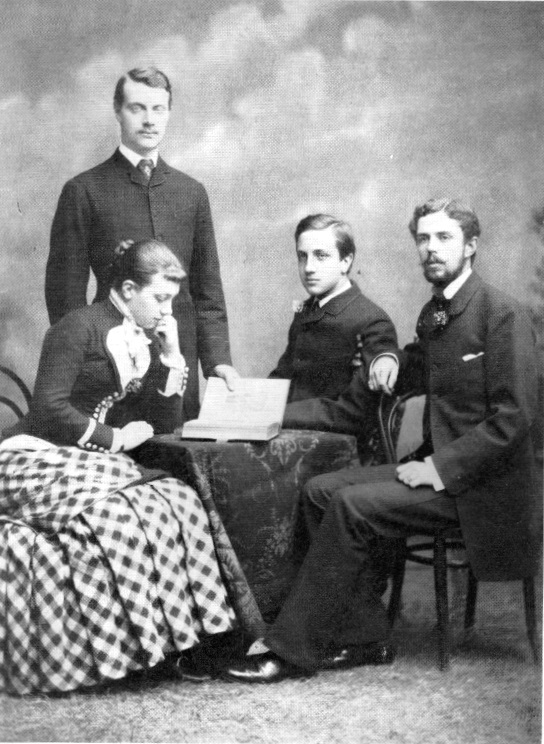

Friedrich’s children (l-r) Victoria, Friedrich and Ludwig with Victoria’s husband, Gustav of Sweden, c1882. source: Wikipedia

Friedrich’s father died in 1852 and was succeeded by Friedrich’s elder brother, Ludwig II. However, Ludwig was deemed mentally ill, and Friedrich was appointed Regent during his reign. When Ludwig died in 1858, Friedrich succeeded him as Grand Duke Friedrich II.

As Grand Duke, Friedrich sided with Prussia in the wars against Austria and France and represented Baden at the Palace of Versailles when his father-in-law was created German Emperor in 1871. Within Baden, he was a strong supporter of constitutional monarchy, which was often at odds with his Prussian in-laws. His reign saw the adoption of civil marriage, as well as free elections to the Baden parliament.

Friedrich and Luise, c1902. source: Wikipedia

Friedrich I died on September 28, 1907 while at his summer residence on the island of Mainau in Lake Constance near Konstanz, Grand Duchy of Baden, now in Baden-Württemberg, Germany He is buried in the Grand Ducal Chapel in the Pheasant Garden in Karlsruhe, Grand Duchy of Baden, now in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Friedrich I was succeeded by his elder son, Friederich II, who would become the last Grand Duke of Baden.

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Baden Resources at Unofficial Royalty