by Scott Mehl © Unofficial Royalty 2016

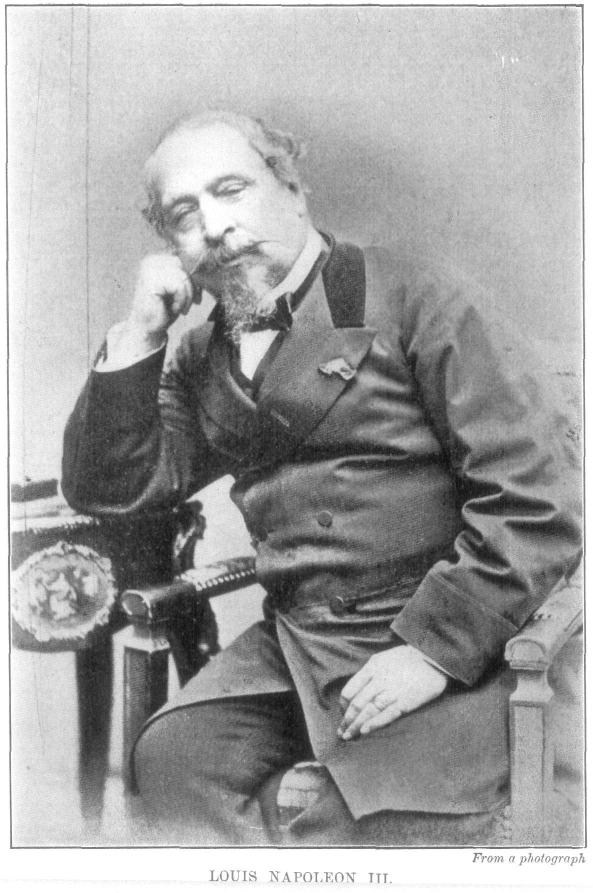

Napoleon III, Emperor of the French; Credit: Wikipedia

Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, was the last monarch of France, reigning from 1852 until 1870. He was born Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte (typically known as Louis-Napoléon) in Paris, France, on April 20, 1808. His parents were Louis Bonaparte, King of Holland (younger brother of Emperor Napoleon I) and Hortense de Beauharnais, the daughter of Emperor Napoleon’s first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, and her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais.

He had two elder siblings:

- Napoléon Louis Charles Bonaparte (1802 – 1807) – died in childhood

- Napoléon Louis Bonaparte, King Louis II of Holland (1804 – 1831) – married his first cousin Charlotte Bonaparte, no issue

Louis-Napoléon’s christening took place at the Palace of Fontainebleau in France on November 4, 1810 – over two years after his birth – with Emperor Napoleon I and his wife, Empress Marie Louise, serving as his godparents.

Following Emperor Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and the subsequent Bourbon Restoration, all members of the Bonaparte family were forced to leave France. Louis-Napoleon and his mother settled in Switzerland, where Hortense purchased Schloss Arenberg. Louis-Napoleon studied for some time in Augsburg, Bavaria, and developed a slight German accent that would remain for the rest of his life.

In 1823, the family moved to Rome, and Louis-Napoleon became involved with the Carbonari, fighting against Austria’s presence in northern Italy. Forced to flee in 1831, he soon made his way back to France. Traveling incognito with his mother using the name Hamilton, they arrived in Paris on April 31, 1831. In a secret meeting, the French King Louis-Philippe permitted them to remain in Paris, provided they remained incognito, and their stay was brief. However, their identities were soon discovered, and they were forced to leave the city just a week later and traveled back to Switzerland.

Louis-Napoléon joined the Swiss Army and began writing about his political views. After he made an unsuccessful coup attempt in October 1836, King Louis Philippe demanded that he be turned over to France, but the Swiss government refused because he was a Swiss citizen. Louis-Napoléon traveled to London, Brazil, and New York, and returned to Switzerland in the fall of 1837 to be at his mother’s deathbed. After the death of his mother, Hortense, on October 5, 1837, Louis-Napoleon spent some time at Schloss Arenberg before returning to London the following year. He soon began plans for another attempt to take the French throne. Sailing to Boulogne in 1840, he was quickly arrested. A quick trial took place, and he was sentenced to life in prison in the fortress of Ham. While imprisoned, he published essays and articles in numerous newspapers and magazines throughout France. Still hoping to fulfill his quest to claim the French throne, Louis-Napoleon escaped from Ham in May 1846. While renovations were being made to his cell, he disguised himself as one of the workers and walked out through the main gates. Following his escape, he quickly made his way back to England. The next month, his father died, leaving Louis-Napoleon as the sole heir to the Bonaparte dynasty.

The French Revolution of 1848 led to King Louis-Philippe’s abdication and the declaration of the Second Republic. Louis-Napoleon quickly left for France, while the deposed King went into exile in England. Ignoring his advisers who urged him to seize power, Louis-Napoleon declared his loyalty to the Republic and returned to London, where he closely watched events unfold in his homeland. In September 1848, he was elected to the French National Assembly and returned to Paris as the country prepared to elect the first President of the French Republic. He immediately announced he would run for resident of the French Republic, and on December 20, 1848, was declared the winner of the election. Taking the title Prince-President, Louis-Napoleon took up residence at the Élysée Palace.

After a failed attempt to change the law, which would have required him to step down at the end of his four-year term, Louis-Napoleon soon saw a chance to take power by force. In December 1851, with the support of several military generals, Louis-Napoleon’s forces took control of the national printing office and newspaper offices. Posters were quickly put up announcing the dissolution of the National Assembly, the return of universal suffrage, and new elections. Quickly overpowering his opponents, Louis-Napoleon established himself as the sole source of rule within France, supported by a referendum held in December 1851, in which the overwhelming majority of voters agreed to his claim of power.

Not content with being a Prince-President, he arranged for the Senate to schedule another referendum to decide if he should be declared Emperor. On December 2, 1852, following an overwhelming vote in his favor, the Second Republic ended and the Second French Empire was declared. Louis-Napoleon took the throne as Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. He quickly made the Tuileries Palace in Paris his official residence.

Napoleon with his wife and son, circa 1862. source: Wikipedia

After being turned down by Princess Carola of Vasa (the granddaughter of the deposed Swedish King Gustaf IV Adolf), and Princess Adelheid of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (a niece of Queen Victoria), Napoleon III found his future bride, Eugénie de Montijo, Countess of Teba and Marquise of Ardales. The two first met in 1849 at a reception at the Eylsée Palace. Just weeks after becoming Emperor, Napoleon announced the couple’s engagement, and they were married a week later. A civil ceremony was held on January 29, 1853, at the Tuileries Palace, followed by a religious ceremony on January 30, 1853, at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. They had one son:

- Napoléon, Prince Imperial (1856 – 1879), unmarried, died in 1879 while fighting in the Anglo-Zulu War

The early years of Napoleon III’s reign saw a heavily censored press and a Legislature nearly unanimous in its support. By the early 1860s, censorship had been eased, and a more liberal regime emerged. The Emperor improved conditions for the poor and ensured that education was mandatory and free for all French citizens. He promoted industry and banking, developed the rail system throughout France, and worked to build strong political and economic relationships with the United Kingdom and other allies throughout Europe.

In July 1870, France entered the Franco-Prussian War. Without significant allied support and with unprepared and limited forces, the French army was quickly defeated. Emperor Napoleon was captured at the Battle of Sedan and surrendered on September 1, 1870. As word reached Paris, the Third Republic was declared on September 4, 1870, ending the French monarchy for the final time. The Prussians held Napoleon III in a castle in Wilhelmshöhe, near Kassel. After peace was established between France and Germany in March 1871, the former Emperor was released and quickly went into exile. Arriving in England on March 20, 1871, Napoleon and his family settled at Camden Place, a large country house in Chislehurst, England.

The last known photo of Emperor Napoleon III, 1872. source: Wikipedia

After falling ill in the summer of 1872 and undergoing two operations, Emperor Napoleon III died at his home, Camden Place, on January 9, 1873. He was initially buried at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Chislehurst, England, but in 1888, his remains were moved to the Imperial Crypt at St. Michael’s Abbey in Farnborough, Hampshire, England.

Sarcophagus of Napoleon III of France at St. Michael’s Abbey; Credit – Wikipedia

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

France Resources at Unofficial Royalty