by Susan Flantzer

© Unofficial Royalty 2022

Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia (1868 – 1917)

(All photos credits – Wikipedia unless otherwise noted)

Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia was born May 18, 1868, at Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo, Russia. He was the eldest son of Alexander III, Emperor of All Russia and Princess Dagmar of Denmark (Empress Maria Feodorovna). His paternal grandparents were Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and his first wife Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine (Empress Maria Alexandrovna). His maternal grandparents were Christian IX, King of Denmark and Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel. Nicholas II married Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, and had four daughters and one son.

Nicholas II had 22 paternal first cousins and 33 maternal first cousins for a total of 55 first cousins. He shares his first cousins with his siblings Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (died young of meningitis), Grand Duke George Alexandrovich, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, and Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna.

********************

Paternal Aunts and Uncles: Children of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and his first wife Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine

- Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna of Russia (1842 – 1849), died from meningitis

- Nicholas Alexandrovich, Tsesarevich of Russia (1843 – 1865), died of meningitis, aged 21

- Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia (1847 – 1909), married Princess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (Maria Pavlovna), had four sons and one daughter

- Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia (1850 – 1908), morganatic marriage to Alexandra Vasilievna Zhukovskaya, had one son

- Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (1853 – 1920), married Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Edinburgh, had one son and four daughters

- Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia (1857 – 1905), married Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine (Elizabeth Feodorovna), no children

- Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia (1860 – 1919), married (1) Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark (Alexandra Georgievna), had one son and one daughter (2) Olga Valerianovna Karnovich, Princess Paley (morganatic marriage), had one son and two daughters

********************

Paternal Aunts and Uncles: Children of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and his morganatic second wife Princess Ekaterina Mikhailovna Dolgorukova, Princess Yurievskaya

- Prince George Alexandrovich Yurievsky (1872 – 1913), married Countess Alexandra von Zarnekau, had one son

- Princess Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya (1874 – 1925), married Georg Nikolaus, Count of Merenberg, had two sons and one daughter

- Prince Boris Alexandrovich Yurievsky (born and died 1876)

- Princess Ekaterina Alexandrovna Yurievskaya (1878 – 1959); married (1) Prince Alexander Vladimirovich Baryatinsky, had two sons (2) Prince Sergei Platonovich Obolensky, no children

********************

Maternal Aunts and Uncles: Children of Christian IX, King of Denmark and Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel

- King Frederik VIII of Denmark (1843 – 1912), married Princess Louise of Sweden, had four sons and four daughters

- Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844 – 1925), married King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, had three sons and three daughters

- Prince Vilhelm of Denmark, who became King George I of Greece (1845 – 1913), married Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, had five sons and three daughters

- Princess Thyra of Denmark (1853 – 1933), married Ernst August II of Hanover, Crown Prince of Hanover, 3rd Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale, had three sons and three daughters

- Prince Valdemar of Denmark (1858 – 1939), married Princess Marie of Orléans, had four sons and one daughter

********************

PATERNAL FIRST COUSINS

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia and Princess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

Grand Duke Alexander Vladimirovich of Russia (1875 – 1877)

Grand Duke Alexander Vladimirovich was born on August 31, 1875, and died nineteen months later on March 16, 1877.

********************

Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia (1876 – 1938)

Kirill married his first cousin Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and had three children. Following the abdication of Nicholas II in 1917, Kirill and his family left Russia. They settled first in Finland, before moving on to Munich and then Zurich. Eventually, they settled permanently in Saint-Briac, France, in the mid-1920s. In addition, they had inherited property in Coburg from his wife’s mother, which they retained until their deaths. Bolstered by a group of supporters, and the laws of the former Imperial Family (under which Kirill was the rightful heir to the throne), on August 31, 1924, Kirill declared himself Emperor of all the Russias. This claim was later taken by his son, Vladimir, and then Vladimir’s daughter, Maria Vladimirovna, who declared herself Head of the Imperial House in 1992.

********************

Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovich of Russia (1877 – 1943)

Boris had a military career and was known as a notorious playboy. After the Russian Revolution, he left Russia with his longtime mistress, Zinaida Rashevskaya, whom he married in exile. The couple had no children Eventually, he settled in France where he spent the rest of his life.

********************

Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich of Russia (1879 – 1956)

In 1921, Andrei married his mistress Matilde Kschessinskaya, one of the most famous ballerinas of the Maryinsky Ballet (now the Kirov Ballet) in St. Petersburg, Russia, known as Princess Romanovskaya-Krasinskaya after her marriage. Mathilde had an affair with Nicholas II before he married. While she was having an affair with Andrei, she was also involved with his cousin Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich. Mathilde’s son Prince Vladimir Romanovsky-Krasinsky could be the son of either Andrei or Sergei but Andrei officially adopted Vladimir. Andrei and Mathilde lived in the south of France until 1929 when they moved permanently to Paris, where Mathilde opened a ballet school.

********************

Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, Princess of Greece (1882 – 1957)

In 1902, Elena married her second cousin, Prince Nicholas of Greece, the son of King George I of Greece and Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia. They had three daughters including Princess Marina of Greece who married Prince George, Duke of Kent, son of King George V of the United Kingdom. Elena is the maternal grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II’s first cousins Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, Princess Alexandra of Kent, and Prince Michael of Kent.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Child of Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia and his (probable) morganatic wife Alexandra Vasilievna Zhukovskaya

Count Alexei Alexandrovich Belevsky-Zhukovsky (1871 – circa 1931)

Alexei married twice: to Princess Maria Petrovna Troubetskaya with whom he had four children and later divorced, and then to Baroness Natalia von Schoeppingk, with who, he had no children. After the Russian Revolution, Alexei remained in the Soviet Union while his wife and children emigrated. He was killed by the Soviets in the Caucasus sometime in 1930, 1931, or 1932.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia and Prince Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Alfred of Edinburgh, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1874 – 1899)

In August 1893, Alfred’s father succeeded to the ducal throne of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and young Alfred became the Hereditary Prince. In January 1899, he was noticeably absent from the celebrations for his parents’ 25th wedding anniversary. The details surrounding his death were never formally given, and vary from source to source. Some say he was suffering from a breakdown, others a tumor, others tuberculosis. More than likely, he was suffering serious effects of syphilis he had contracted some years earlier. It is generally accepted that Alfred shot himself while the rest of the family was gathered for the anniversary celebrations. He survived the gunshot and was cared for at Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha, Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, before being moved, against the doctors’ recommendation, to the Martinnsbrunn Sanatorium in Gratsch, near Meran, Austria, where 24-year-old Alfred died.

********************

Princess Marie of Edinburgh, Queen of Romania (1875 – 1938)

In 1893, Marie married Crown Prince Ferdinand of Romania. The couple officially had six children. The two youngest children are believed to have been fathered by Marie’s lover but were formally acknowledged by Ferdinand as his own. Being very free-spirited, Marie found the strict Romanian court to be stifling. Her husband’s uncle King Carol controlled every aspect of the couple’s lives. In 1914, Ferdinand became King of Romania upon the death of his uncle and reigned until his death in 1927. Marie spent her remaining years enjoying the company of her grandchildren and enjoying her homes at Bran Castle and Balchik Palace. Throughout the years, she had written her memoirs, which were published in several volumes.

********************

Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna of Russia (1876 – 1936)

In 1894, Victoria Melita married her first cousin Ernst II, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine. They were both grandchildren of Queen Victoria. The couple had one surviving child Princess Elisabeth who sadly died of typhoid at age 8. Victoria Melita and Ernst were terribly mismatched but waited until after the death of their grandmother Queen Victoria to divorce. In 1905, Victoria Melita married another first cousin Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia, also a first cousin of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia (see above). The couple had two daughters and one son. Following the abdication of Nicholas II in 1917, the family left Russia. They settled first in Finland, before moving on to Munich and then Zurich. Eventually, they settled permanently in Saint-Briac, France, in the mid-1920s. In addition, they had inherited property in Coburg from Victoria Melita’s mother, which they retained until their deaths.

********************

Princess Alexandra of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (1878 – 1942)

Princess Alexandra of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (1878 – 1942)

In 1896, that Alexandra married Prince Ernst of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. Alexandra and Ernst were second cousins – their grandmothers, Queen Victoria and Princess Feodora of Leiningen were half-sisters. The couple had two sons and three daughters. After her mother’s death in 1920, Alexandra inherited Palais Edinburg in Coburg, and, along with her sisters and leased Schloss Rosenau from the state until the late 1930s. In 1937, Alexandra joined her husband, and some of her children, as a member of the Nazi Party.

********************

Princess Beatrice of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duchess of Galliera (1884-1966)

In 1906, Beatrice’s cousin, Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, married King Alfonso XIII of Spain in Madrid, Spain. It was at the wedding that Beatrice met her future husband, Alfonso XIII’s first cousin Infante Alfonso of Spain. The couple married in 1909, in Coburg. A civil ceremony was held at Schloss Rosenau, followed by a Catholic ceremony at St. Augustine’s Church, and a Lutheran ceremony at Schloss Callenberg. Unlike her cousin, Victoria Eugenie, Beatrice chose not to convert to Catholicism prior to her marriage. She did later convert in 1913. Beatrice and Alfonso had three sons.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia and his first wife Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia, Princess of Sweden,

Princess Sergei Mikhailovich Putyatin (1890 – 1958)

Maria Pavlovna was a first cousin of both Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. When Maria Pavlovna was only seventeen months old, her mother died shortly after giving premature birth to her second child, Maria Pavlovna’s brother. In 1908, Maria Pavlovna married Prince Wilhelm of Sweden, son of King Gustav V of Sweden. The couple had one son Lennart but the marriage was not a happy one. In 1913, Maria left her husband and son and returned to Russia which caused a great scandal in Sweden. Her marriage was officially dissolved and then confirmed by an edict issued by Nicholas II. In 1917, Maria Pavlovna married Prince Sergei Mikhailovich Putyatin and the couple had one son who died in 1919. Maria Pavlovna and Sergei Mikhailovich were able to leave Russia and they settled in Paris, France but they divorced in 1923. In 1929, Maria emigrated to the United States where she wrote her two best-selling- memoirs, The Education of a Princess and A Princess in Exile. She also worked for the department store Bergdorf Goodman in New York City purchasing fashionable clothing from France. Maria’s interest in photography got her jobs with Hearst and Vogue as a photojournalist. In 1937, Maria Pavlovna was reunited with her son Lennart at his estate on the island of Mainau in Lake Constance, Germany.

********************

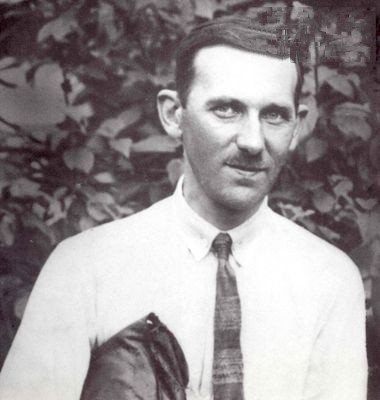

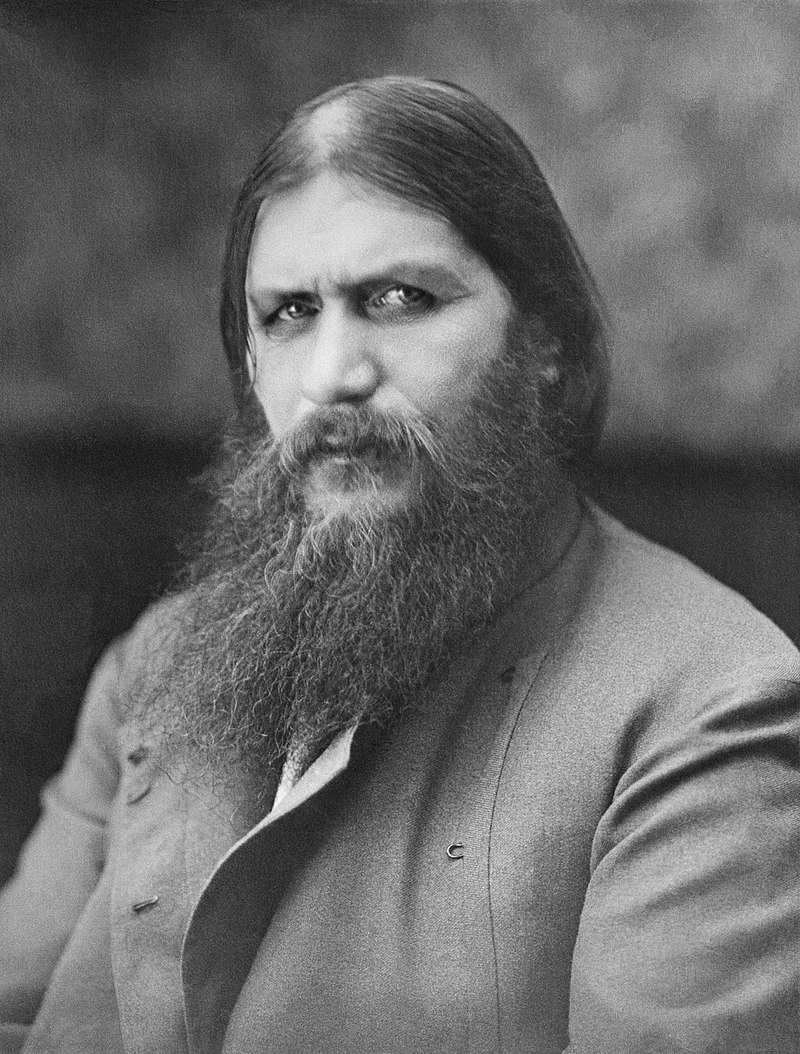

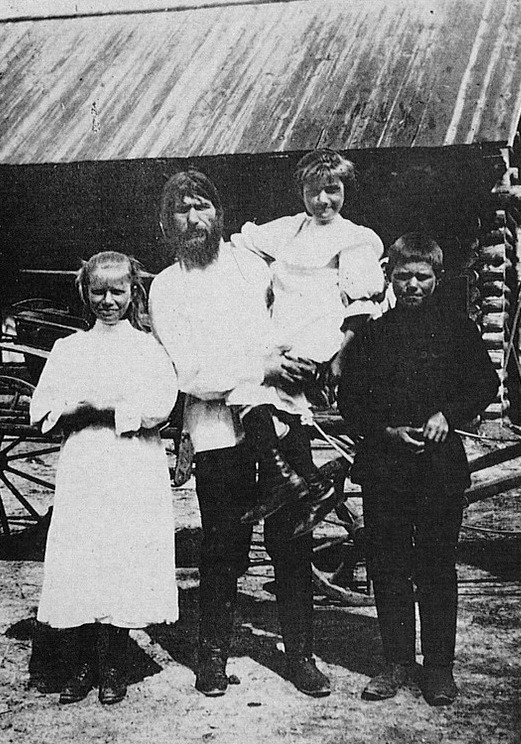

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia (1891–1942)

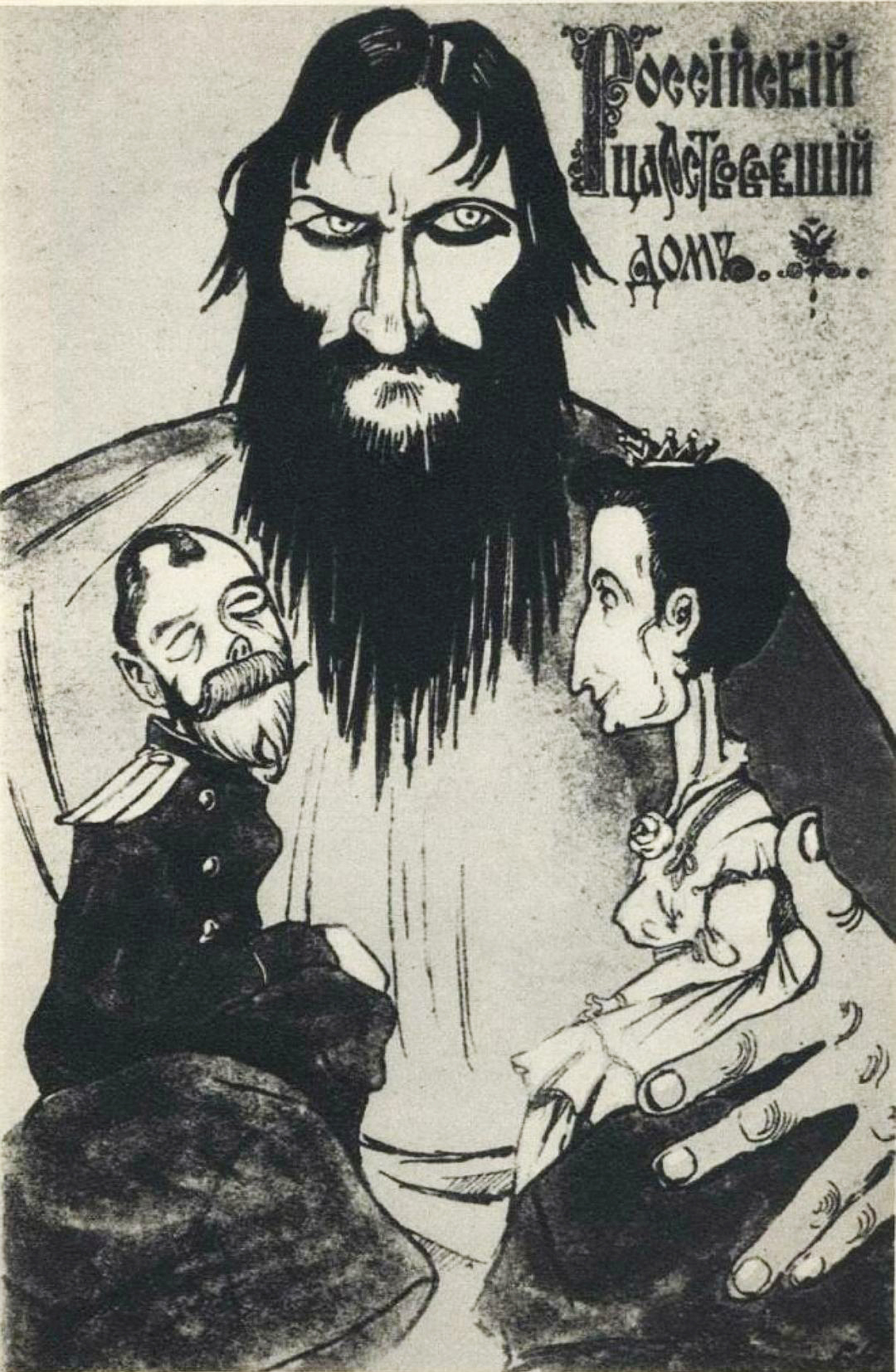

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia was one of the conspirators in the murder of Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin and also a first cousin of both Nicholas II, the last Emperor of All Russia and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Shortly after Dmitri’s birth, his 21-year-old mother died from childbirth complications. Dmitri and his sister were brought up by English nannies and mostly lived with their paternal uncle and aunt, Grand Duke Sergei and Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia. Dmitri participated in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm in the Equestrian Individual and Team Jumping events. After the murder of Rasputin, Dmitri was exiled to Persia (now Iran), a move that most likely saved his life during the Russian Revolution. In 1926, in the Russian Orthodox Church in Biarritz, France, Dmitri married the rich American heiress Audrey Emery, and the couple had one son.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich and his morganatic second wife Olga Karnovich

Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Paley (1897 – 1918)

Vladimir grew up in Paris and then attended the Corps des Pages, a military academy in Saint Petersburg, Russia. During World War I, he fought with the Emperor’s Hussars and was a decorated war hero. A talented poet from an early age, Vladimir published two volumes of poetry and wrote several plays and essays. Vladimir was one of the five Romanovs executed on July 18, 1918, with Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, the sister of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

- Wikipedia: Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Paley

- Unofficial Royalty: Execution of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna and Five Other Romanovs

********************

Princess Irina Pavlovna Paley (1903 – 1990)

Both Irina’s father Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich and her brother Prince Vladimir Pavlovich Paley, were killed by the Bolsheviks. Irina, her mother, and her sister Natalia later escaped to France in 1920. In 1923, Irina married her first cousin once removed, Prince Feodor Alexandrovich of Russia, son of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia, and the couple had one son. in Paris. During her marriage to Feodor, Irina began an affair with Count Hubert de Monbrison and gave birth to Hubert’s daughter. Irina and Feodor were divorced in 1936, and she married Hubert in 1950,

********************

Princess Natalia Pavlovna Paley (1905–1981)

After the Russian Revolution, Natalia first lived in France and later in the United States where she became a naturalized American citizen. She became a fashion model and briefly pursued a career as a film actress. In 1927, Natalia married Lucien Lelong, a French fashion designer. The couple had no children and divorced in 1937. Soon after the divorce, Natalia married John Chapman Wilson, an American theatre director and producer. The couple had no children and the marriage lasted until Wilson’s death in 1961.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Prince George Alexandrovich Yurievsky and Countess Alexandra von Zarnekau

Alexander Georgiyevich Yuryevsky, Prince Yuryevsky (1900 – 1988)

Alexander was the paternal grandson of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and his morganatic second wife Princess Ekaterina Mikhailovna Dolgorukova, Princess Yurievskaya. After the divorce of his parents, Alexander went to live with his paternal grandmother Princess Yurievskaya who had moved to Nice, France after the assassination of her husband Alexander II. Alexander married Ursule Anne Marie Beer de Grüneck and the couple had one son.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Princess Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya and Count Georg-Nikolaus von Merenberg

The surviving two children of Princess Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya and Count Georg-Nikolaus von Merenberg: Countess Olga Ekaterina Adda von Merenberg and Count Georg-Michael von Merenberg, circa 1900

The children of Princess Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya are the paternal grandchildren of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and his morganatic second wife Princess Ekaterina Mikhailovna Dolgorukova, Princess Yurievskaya. Their father Count Georg-Nikolaus von Merenberg was the son of Prince Nicholas Wilhelm of Nassau (brother of the Grand Duke Adolph of Luxembourg) and Natalia Alexandrovna Pushkina), daughter of the Russian writer Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin.

Count Alexander-Adolf von Merenberg (1897 – 1898)

Alexander-Adolf was the twin of Count Georg-Michael von Merenberg but he died when he was six months old.

********************

Count Georg-Michael von Merenberg (1897 – 1965)

In 1926, Georg-Michael married Baroness Paulette von Koever de Györgys-Saint-Miklós. The marriage was childless and the marriage ended in divorce after two years. Georg-Michael married Elisabeth Müller-Ury in 1940 and the couple had one daughter. In 1941, Georg-Michael was drafted into the German Army and sent to the Eastern Front. He was an opponent of the Nazi Party and was tried twice by a military tribunal: the first time, for refusing to do the Nazi Party salute, the second time, for desecrating the Nazi Party symbol.

********************

Countess Olga Ekaterina Adda von Merenberg (1898 – 1983)

Olga married Count Mikhail Tarielovich Loris-Melikov and they had one son.

********************

Paternal First Cousins: Children of Princess Ekaterina Alexandrovna Yurievskaya and Prince Alexander Vladimirovich Baryatinsky

The children of Princess Ekaterina Alexandrovna Yurievskaya are the paternal grandchildren of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia and his morganatic second wife Princess Ekaterina Mikhailovna Dolgorukova, Princess Yurievskaya.

Prince Andrei Baryatinsky (1902 – 1944)

Andrei Alexandrovich was born in Paris, France and after the death of his father and grandfather, he inherited one of the richest fortunes in Russia. In 1925, he married Marie Paule Jedlinski and they had one daughter.

********************

Prince Alexander Baryatinsky (1905 – 1992)

Alexander Alexandrovich was born in Paris, France. He was married twice but had no children

*****************

MATERNAL FIRST COUSINS

Maternal First Cousins: Children of Frederick VIII, King of Denmark and Princess Louise of Sweden

Christian X, King of Denmark of Denmark (1870 – 1947)

Christian X married Princess Alexandrine of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1898 and had two sons including Frederik IX, King of Denmark. In 1940, during World War II, Germany occupied Denmark. Unlike King Haakon VII of Norway (Christian’s brother, born Prince Carl of Denmark) and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, both of whom went into exile during the German occupation of their countries, King Christian X remained in Denmark. He is remembered for his daily horse ride without a guard through the streets of Copenhagen during the Nazi occupation of Denmark, a symbol of Danish sovereignty.

*****************

Haakon VII, King of Norway (1872 – 1957)

A Danish prince who became King Haakon VII of Norway and one of a few elected monarchs, he was born Prince Carl of Denmark. In 1896, Carl married his first cousin Princess Maud of Wales (who was also a first cousin of Nicholas II). The couple had one son, born Prince Alexander of Denmark, later King Olav V of Norway.

In 1905, upon the dissolution of the Union between Sweden and Norway, the Norwegian government began searching for candidates to become King of Norway. Because of his descent from prior Norwegian monarchs, as well as his wife’s British connections, Carl was the overwhelming favorite. Before accepting, Carl insisted that the voices of the Norwegian people be heard in regards to retaining a monarchy. Following a referendum with a 79% majority in favor, Prince Carl was formally offered and then accepted the throne. He took the name Haakon VII and his two-year-old son was renamed Olav and became Crown Prince of Norway.

*****************

Princess Louise of Denmark, Princess of Schaumburg-Lippe (1875 – 1906)

In 1896, Louise married Prince Frederick of Schaumburg-Lippe and the couple had three children. Louise suffered from depression and homesickness and spent much time visiting her family in Denmark, staying for two to three months at a time. Her father also came and visited with her each year. She died at the age of 31, and although the official cause of her death was meningitis, it is suspected that Louise drowned herself in a lake. She had tried this before but had been saved by the palace gardener.

*****************

Prince Harald of Denmark (1876 – 1949)

Harald served in the Royal Danish Army for most of his life and reached the rank of Lieutenant General. In 1909, Harald married his second cousin Princess Helena of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. Harald and Helena had five children.

*****************

Princess Ingeborg of Denmark, Princess of Sweden ( 1878 – 1958)

In 1897, Ingeborg married Prince Carl of Sweden. Carl and Ingeborg had four children including Märtha who married her first cousin the future King Olav V of Norway (Märtha died before her husband became king) and Astrid who married King Leopold III of Belgium. The current royal families of Belgium, Luxembourg, and Norway descend from Carl and Ingeborg. Belgian Kings Baudouin and Albert II, Norwegian King Harald V, and Grand Duchess Josephine-Charlotte of Luxembourg, the wife of Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg are all grandchildren of Carl and Ingeborg.

*****************

Princess Thyra of Denmark (1880 – 1945)

Thyra never married and lived her entire adult life in an apartment on Amaliegade, a street in Copenhagen, Denmark, close to Amalienborg Palace, where the Danish royal family lived. She was considered very friendly and understanding, and her apartment was a popular meeting place for her siblings and her relatives.

*****************

Prince Gustav of Denmark (1887 – 1944)

As a child, Gustav suffered from an illness that made him severely overweight. He had a brief career in the military. Gustav never married and he spent much of his life with his unmarried sister, Princess Thyra. Together, they often visited their brother King Haakon VII of Norway.

*****************

Princess Dagmar Of Denmark, Mrs. Castenskiold (1890 – 1961)

In 1922, Dagmar married Jørgen Castenskjold, the son of Anton Castenskiold, the Royal Danish Court Chamberlain. Dagmar and Jørgen had five children.

*****************

Maternal First Cousins: Children of Princess Alexandra of Denmark, Queen of the United Kingdom and Edward VII, King of the United Kingdom

Prince Albert Victor of the United Kingdom, Duke of Clarence and Avondale (1864 – 1892)

Prince Albert Victor, known as Eddy, was the eldest child of the then Prince and Princess of Wales, the future King Edward VII of the United Kingdom and Queen Alexandra, born Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Eddy, who was inattentive and lazy, never excelled in his studies. Perhaps this was due to his premature birth which can be associated with learning disabilities. On December 3, 1891, Eddy and Princess Victoria Mary of Teck (Mary or May) became engaged. The wedding was set for February 27, 1892, but on January 14, 1892, Eddy died from pneumonia. The following year, Princess Victoria Mary of Teck married Eddy’s brother George, and they eventually became the beloved King George V and Queen Mary.

*****************

George V, King of the United Kingdom (1865 – 1936)

After the death of George’s elder brother Prince Eddy (above), George, now second in the line of succession to the British throne, and Eddy’s fiancee Mary spent much time together. As time passed and their common grief eased, there was hope that a marriage might take place between them. The couple married on July 6, 1893, and eventually became the beloved King George V and Queen Mary. George and Mary had six children. During World War I, on July 17, 1917, King George V issued a proclamation changing the name of the British Royal Family from the German Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the English Windsor, due to the anti-German sentiment.

*****************

Louise, Princess Royal and Duchess of Fife (1867 – 1931)

In 1889, Louise married a husband from the British nobility. Seventeen years older than his bride, Alexander William George Duff was the only son of James Duff, 5th Earl Fife and Lady Agnes Hay, daughter of the 18th Earl of Erroll and Lady Elizabeth FitzClarence who was an illegitimate daughter of King William IV. Louise and her husband had two daughters. As the eldest daughter of King Edward VII, Louise was created Princess Royal during her father’s reign, in 1905.

*****************

Princess Victoria of the United Kingdom (1868 – 1935)

Victoria’s elder sisters Louise and Maud escaped into marriage, leaving her at home as her mother’s constant companion. She had several suitors but her mother actively discouraged her from marrying anyone. Instead, Victoria remained a companion to her mother, Queen Alexandra, whom she lived with until the Queen’s death in 1925. Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia, Toria’s first cousin, described her as little more than “a glorified maid.” When her mother died, Victoria was 57 and was able to live her own life at last. She purchased a country home, Coppins, in Iver, Buckinghamshire, England. Toria became active in the village life of Iver and was the honorary president of the Iver Horticultural Society.

*****************

Princess Maud of Wales, Queen of Norway

In 1896, Maud married her first cousin Prince Carl of Denmark (later King Haakon VII of Norway), who was also a first cousin of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia. The couple had one son, born Prince Alexander of Denmark, later King Olav V of Norway. In 1905, upon the dissolution of the Union between Sweden and Norway, the Norwegian government began searching for candidates to become King of Norway. Because of his descent from prior Norwegian monarchs, as well as his wife’s British connections, Carl was the overwhelming favorite. He took the name Haakon VII and his two-year-old son was renamed Olav and became Crown Prince of Norway. Maud and her husband made certain that their son was raised as a Norwegian, although Maud never became fluent in Norwegian. Maud never gave up her love for her native country and visited often. However, she did fulfill her duties as Queen of Norway. Maud became active in women’s rights and in the welfare of unmarried women.

*****************

Prince Alexander John of Wales (born and died 1871)

Prince Alexander John of Wales was born prematurely at Sandringham House in Norfolk, England on April 6, 1872, at 2:45 p.m., and died the next day. He was christened privately in the evening after his birth. The christening was attended by his parents, The Prince and Princess of Wales, a lady-in-waiting, and a doctor who had been at the birth.

*****************

Maternal First Cousins: Children of George I, King of Greece and Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna of Russia

Note: George I, King of Greece was born Prince Vilhelm of Denmark, the brother of Princess Dagmar of Denmark (Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia), Nicholas II’s mother.

Constantine I, King of Greece (1868 – 1923)

In 1889, Constantine married Princess Sophie of Prussia, daughter of Friedrich III, German Emperor and Victoria, Princess Royal, the eldest child of Queen Victoria. Sophie and Constantine had six children and there is a 23-year age gap between their eldest and youngest child. In 1913, Constantine’s father King George I was assassinated and he acceded to the Greek throne as King Constantine I. Constantine reigned until 1917 when he was forced to abdicate. He reigned for a second time, from 1920 – to 1922 when he was again forced to abdicate.

*****************

Prince George of Greece and Denmark (1869 – 1957)

In 1907, George married Princess Marie Bonaparte, daughter of Prince Roland Bonaparte, a grandson of Lucien Bonaparte, Emperor Napoleon I’s brother. Marie was quite wealthy in her own right, having been left a vast fortune by her mother, Marie-Félix Blanc, the daughter of François Blanc who was the principal developer of Monte Carlo and the Monte Carlo Casino. George and Marie had a son and a daughter.

*****************

Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna of Russia (1870 – 1891)

Alexandra’s family usually spent their vacations in Russia or Denmark with their British, Danish, and Russian relatives and so Alexandra had early contact with the family of Alexander II, Emperor of all Russia, including her future husband Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich who was the youngest child of Alexander II and his wife Empress Maria Alexandrovna, born Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine. In 1888, Alexandra and Grand Duke Paul married and Alexandra became Grand Duchess Alexandra Georgievna of Russia. The couple had two children: Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, who were also first cousins (through their father) of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia. Alexandra gave birth prematurely to her son, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and then she lapsed into a coma. She did not recover consciousness and died six days later on September 24, 1891, at the age of 21.

*****************

Prince Nicholas of Greece and Denmark (1872 – 1938)

In 1902, Nicholas married his second cousin Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia. Elena was the only daughter of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia (a son of Alexander II, Emperor of All Russia) and Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Elena was also a first cousin of Nicholas II, Emperor of All Russia. Nicholas and Elena had three daughters including Princess Marina of Greece who married Prince George, Duke of Kent, son of King George V of the United Kingdom. Nicholas and Elena are the maternal grandparents of Queen Elizabeth II’s first cousins Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, Princess Alexandra of Kent, and Prince Michael of Kent.

*****************

Princess Maria of Greece and Denmark, Grand Duchess Maria Georgievna of Russia (1876–1940)

In 1900, Maria married Grand Duke George Mikhailovich of Russia. Maria and her husband had two daughters. When World War I began, Maria was living in Harrogate, England with her two daughters and chose to remain there and not return to Russia. Her husband, like many in the Russian Imperial Family, was murdered by the Bolsheviks with three other Grand Dukes of Russia in January 1919, leaving Maria a widow. In 1920, Maria was able to return to Greece when her eldest brother, King Constantine I, was brought back to power. She traveled aboard a Greek destroyer commanded by Admiral Pericles Ioannidis, and a romance developed. The couple married two years later, on December 16, 1922, in Wiesbaden, Germany. They had no children.

*****************

Princess Olga of Greece and Denmark (born and died 1870)

Olga died at the age of seven months.

*****************

Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark (1882 – 1944)

At the coronation of King Edward VII of the United Kingdom in August 1902, Andreas first met Princess Alice of Battenberg. She was the eldest daughter of Prince Louis of Battenberg and Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. The couple married in 1903, and over the next 18 years, they had five children including Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the husband of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom. By the early 1930s, Andreas had less and less contact with his family. His wife suffered a nervous breakdown and was institutionalized, his four daughters had all married into former German royal families, and his son was attending school first in Germany and then in the United Kingdom. Somewhat at a loss, having been basically forced into a life of retirement, Andreas moved to the French Riviera. There, he enjoyed a life of leisure, spending much of his time living aboard the yacht of his mistress Countess Andrée de La Bigne.

*****************

Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark (1888 – 1940)

In 1920, Christopher married Nancy Stewart Worthington Leeds, an American widow of a Cleveland tin manufacturer. The bride, who was a divorcee as well as a widow, was fifteen years older than Christopher. During her marriage to Christopher, Nancy was known as Princess Anastasia after she joined the Greek Orthodox Church. Sadly, Anastasia was diagnosed with cancer not long after the wedding and died in London in 1923. Six years later, Christopher made a more acceptable dynastic marriage to French Princess Francoise of Orleans, and the couple had one son.

*****************

Maternal First Cousins: Children of Princess Thyra of Denmark, Crown Princess of Hanover and Ernst August II, Crown Prince of Hanover and 3rd Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale

Princess Marie Louise of Hanover and Cumberland, Margravine of Baden (1879 – 1948)

In 1900, Marie Louise married Prince Maximilian of Baden, later titular Margrave of Baden and they had a son and a daughter. Their son Prince Berthold of Baden married Princess Theodora of Greece and Denmark, a daughter of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg. Prince Berthold was the brother-in-law of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

*****************

Georg Wilhelm, Hereditary Prince of Hanover (1880 – 1912)

Georg Wilhelm was an enthusiastic fan of automobile racing and took part in races several times. He was killed in a car accident after skidding on a newly laid road surface and hitting a tree while driving to the funeral of his uncle King Frederik VIII of Denmark. His valet was also killed in the accident.

- Wikipedia: Georg Wilhelm, Hereditary Prince of Hanover (link in German)

*****************

Princess Alexandra of Hanover and Cumberland, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1882 – 1963)

In 1904, Alexandra married Friedrich Franz IV, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and they had five children. Following her husband’s abdication on November 14, 1918, after World War I, the family was forced to leave the Grand Duchy. They traveled to Denmark at the invitation of Queen Alexandrine, Friedrich Franz’s sister, and stayed for a year at Sorgenfri Palace. The following year, they were permitted to return to Mecklenburg and recovered several of their properties.

*****************

Princess Olga of Hanover and Cumberland (1884 – 1958)

Olga never married and lived with her family in Gmunden, Austria. She was a companion to her parents until their respective deaths in 1923 and 1933. Shortly before Olga’s death in 1958, her nephew Prince Ernest August IV of Hanover and his wife Princess Ortrud of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg named their daughter after her.

*****************

Prince Christian of Hanover and Cumberland (1885 – 1901)

Prince Christian fell ill with appendicitis which was not recognized and treated. He died at the age of 16 from the peritonitis caused by the appendicitis being untreated.

- Wikipedia Prince Christian of Hanover and Cumberland (link in German)

*****************

Ernst August III, Prince of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick (1887 – 1953)

Ernst August was the last reigning Duke of Brunswick and the pretender to the throne of Hanover. In 1913, he married Princess Viktoria Luise of Prussia, the only daughter of Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia. Their wedding was one of the last large gatherings of European royalty before World War I began the following year. Ernst August and Viktoria Luise had five children. Following his father’s death in 1923, Ernst August became head of the House of Hanover. However, he was unable to inherit his father’s British title, Duke of Cumberland, as that title had been suspended by the British government under the Titles Deprivation Act of 1917.

*****************

Maternal First Cousins: Children of Prince Valdemar of Denmark and Princess Marie of Orléans

Prince Aage, Count of Rosenborg (1887 – 1940)

In 1914, Aage married Matilda Calvi dei conti di Bergolo. Due to the unequal marriage, he renounced his place in the line of succession to the Danish throne, forfeited the title Prince of Denmark, and assumed the style of Prince Aage, Count of Rosenborg. Aage and Matilda had one son, and they divorced in 1939. In 1922, Aage received permission from King Christian X of Denmark to leave the Danish army in order to join the French Foreign Legion.

*****************

Prince Axel of Denmark (1888 – 1964)

Axel was a popular patron of sports. He was a longtime and active member of the International Olympic Committee. In 1919, Axel married Princess Margaretha of Sweden, his first cousin once removed, and the couple had two sons. Axel and his wife often officially represented King Christian X and King Frederik IX at events abroad.

********************

Prince Erik, Count of Rosenborg (1890 – 1950)

In 1924, Erik married Lois Frances Booth, a Canadian. Due to the unequal marriage, he renounced his place in the line of succession to the Danish throne, forfeited the title Prince of Denmark, and was styled Prince Erik, Count of Rosenborg. Erik and his wife had one son and one daughter and divorced in 1937.

********************

Prince Viggo, Count of Rosenborg (1893 – 1970)

In 1924, Viggo married American Eleonor Green. Due to the unequal marriage, he renounced his place in the line of succession to the Danish throne, forfeited the title Prince of Denmark, and was styled Prince Viggo, Count of Rosenborg. Viggo and Eleanor had no children.

********************

Princess Margrethe of Denmark, Princess of Bourbon-Parma (1895 – 1992)

Margrethe’s parents Prince Valdemar of Denmark and Princess Marie of Orléans had agreed that all their sons would be raised Lutheran, their father’s religion, and all their daughters Roman Catholic, their mother’s religion. Margrethe was the first Danish princess since the Reformation raised a Roman Catholic. In 1921, she married Prince René of Bourbon-Parma, and the couple had three sons and one daughter including Princess Anne of Bourbon-Parma who married King Michael I of Romania.

********************

This article is the intellectual property of Unofficial Royalty and is NOT TO BE COPIED, EDITED, OR POSTED IN ANY FORM ON ANOTHER WEBSITE under any circumstances. It is permissible to use a link that directs to Unofficial Royalty.

Works Cited

- Lundy, D. (2022). Main Page. [online] Thepeerage.com. Available at: http://www.thepeerage.com/. (for genealogy information)

- Unofficial Royalty. (2022). Unofficial Royalty. [online] Available at: https://www.unofficialroyalty.com. (for biographical and genealogy information)

- Wikipedia. (2022 Main Page. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/. (for biographical and genealogy information)